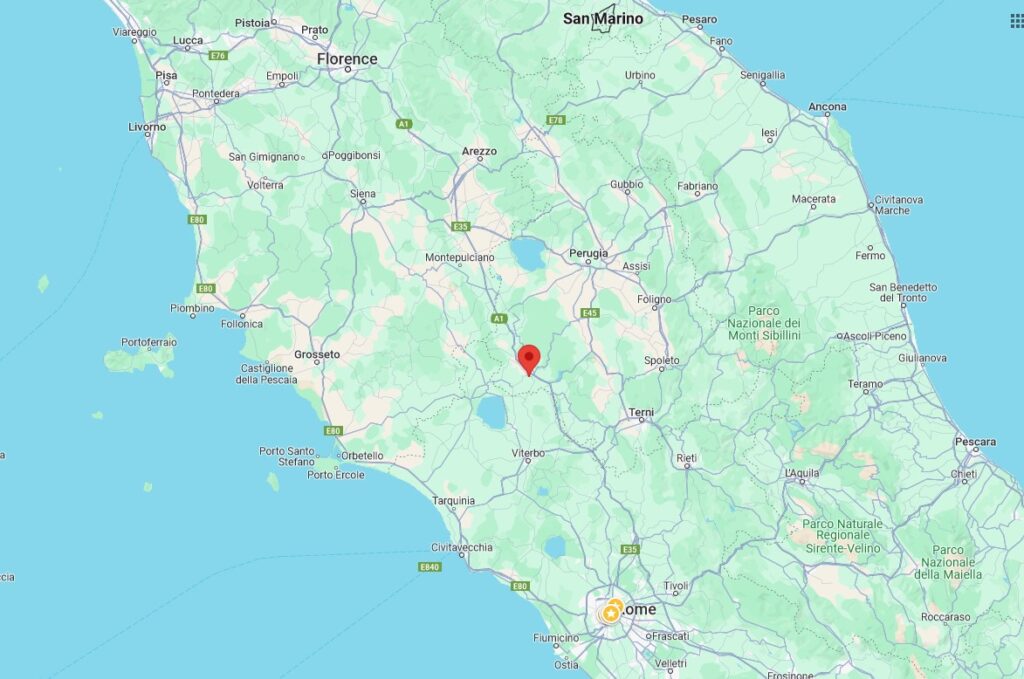

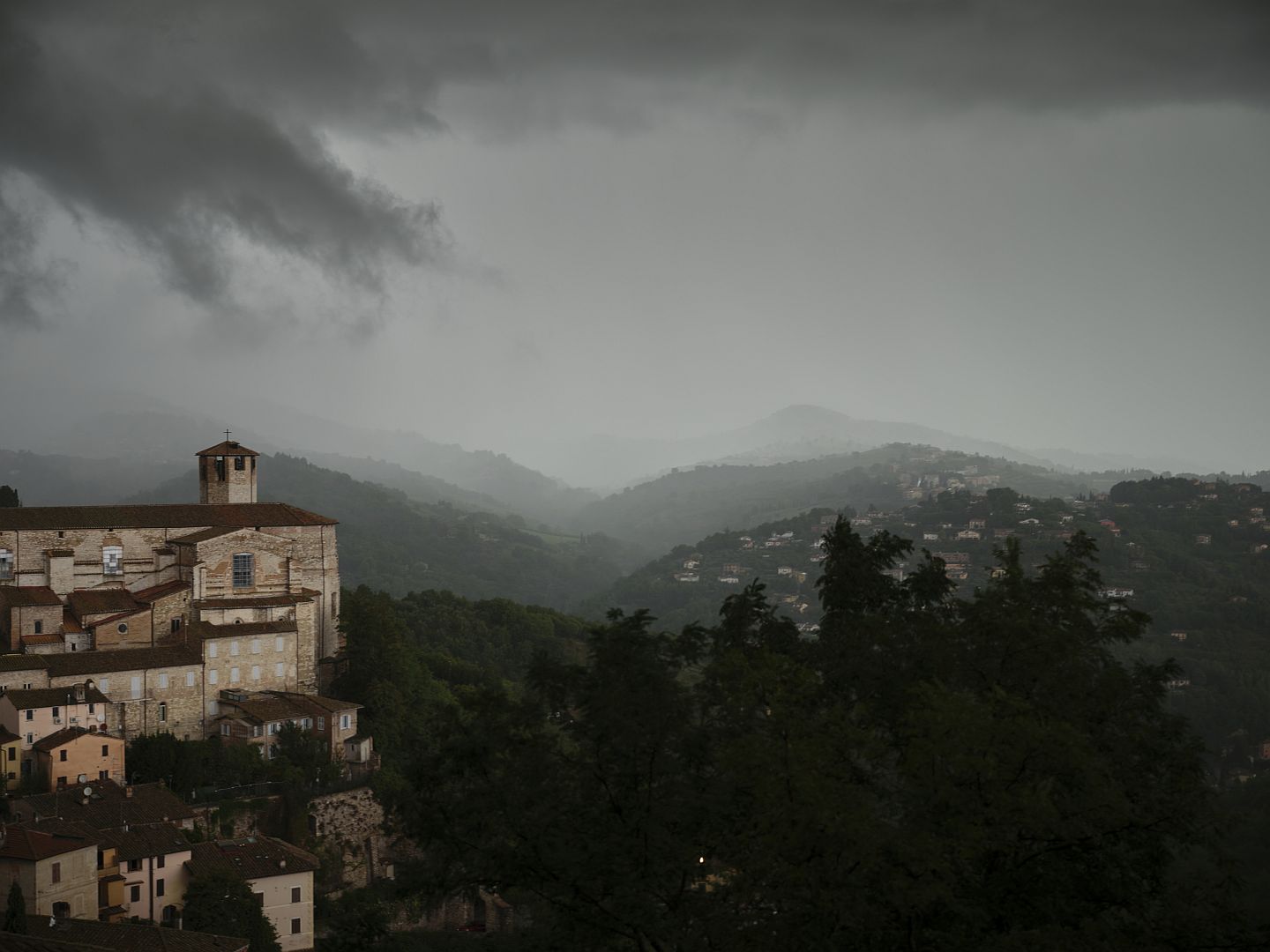

Todi is a town in Umbria, rising on a rugged hilltop beside the River Tiber. These days it is known for its almost perfectly-preserved medieval town centre, but there are traces of a far more ancient town, and many of them are not hard to find.

Todi has two things that marked it as a good site for a town – firstly a steep defensible hill, and secondly, despite its height above the valley, it is a hill on which there are sources of fresh water. Water falls on the Martani mountains to the east and seeps down through the limestone, but then gets trapped under a layer of impermeable clay in the valley, where it builds up pressure. Todi’s hill is a plug of limestone up through which the water is forced, emerging in multiple places as springs.

So it was the obvious place for a settlement, and there are signs of there having been continuous occupation since Neolithic times, when the river valley below was variously swampy or even inundated by a huge lake.

The Legend of the Eagle

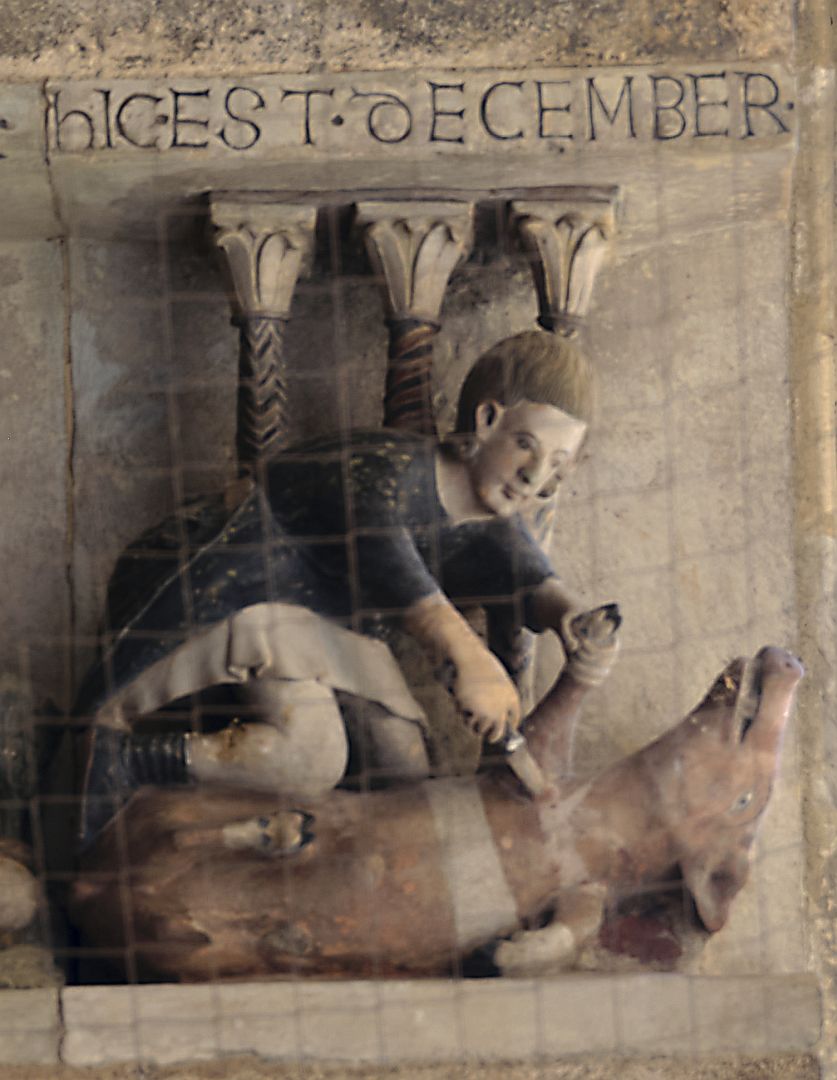

However the foundation myth of Todi is a bit more elaborate. According to the story, Todi was originally intended to be built by the banks of the Tiber, and after the first morning’s work, the builders stopped for lunch (that part is believable, at any rate). But as soon as the tablecloth was laid, an eagle swooped down, seized it, and carried it away to the top of the hill. Augurs interpreted this event as a sign that the town should have been built up there, and so the plan was changed. And thus it also was that the eagle became emblematic of Todi. It is still on the town’s coat of arms.

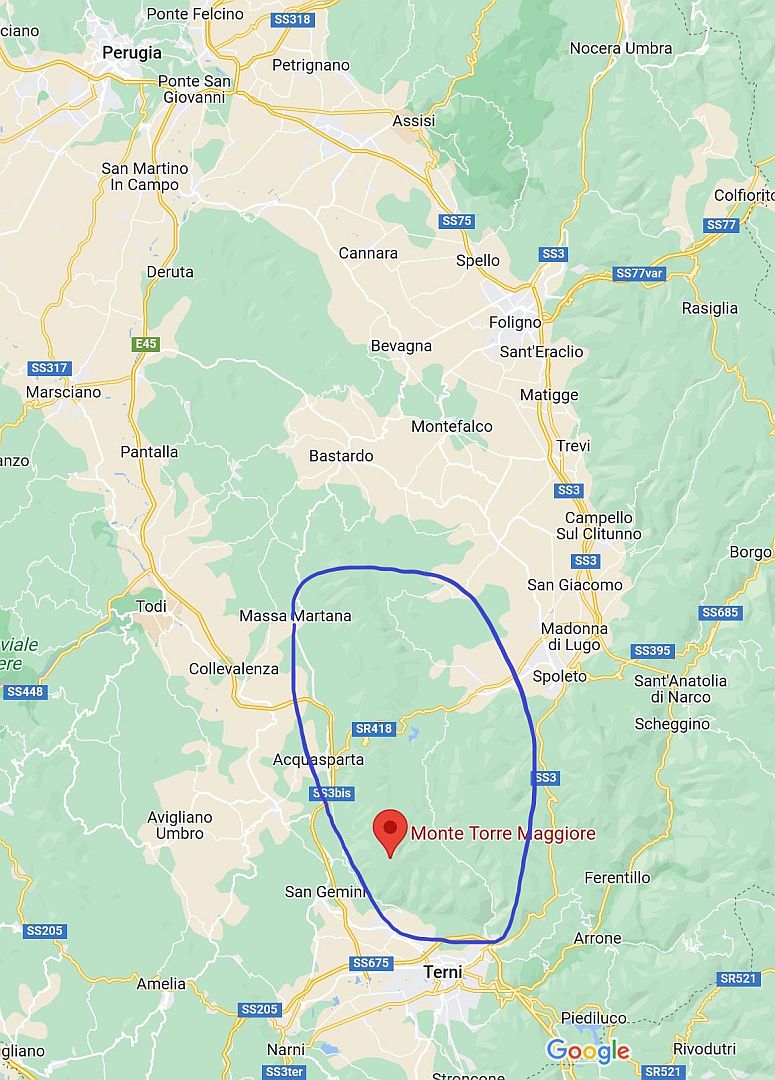

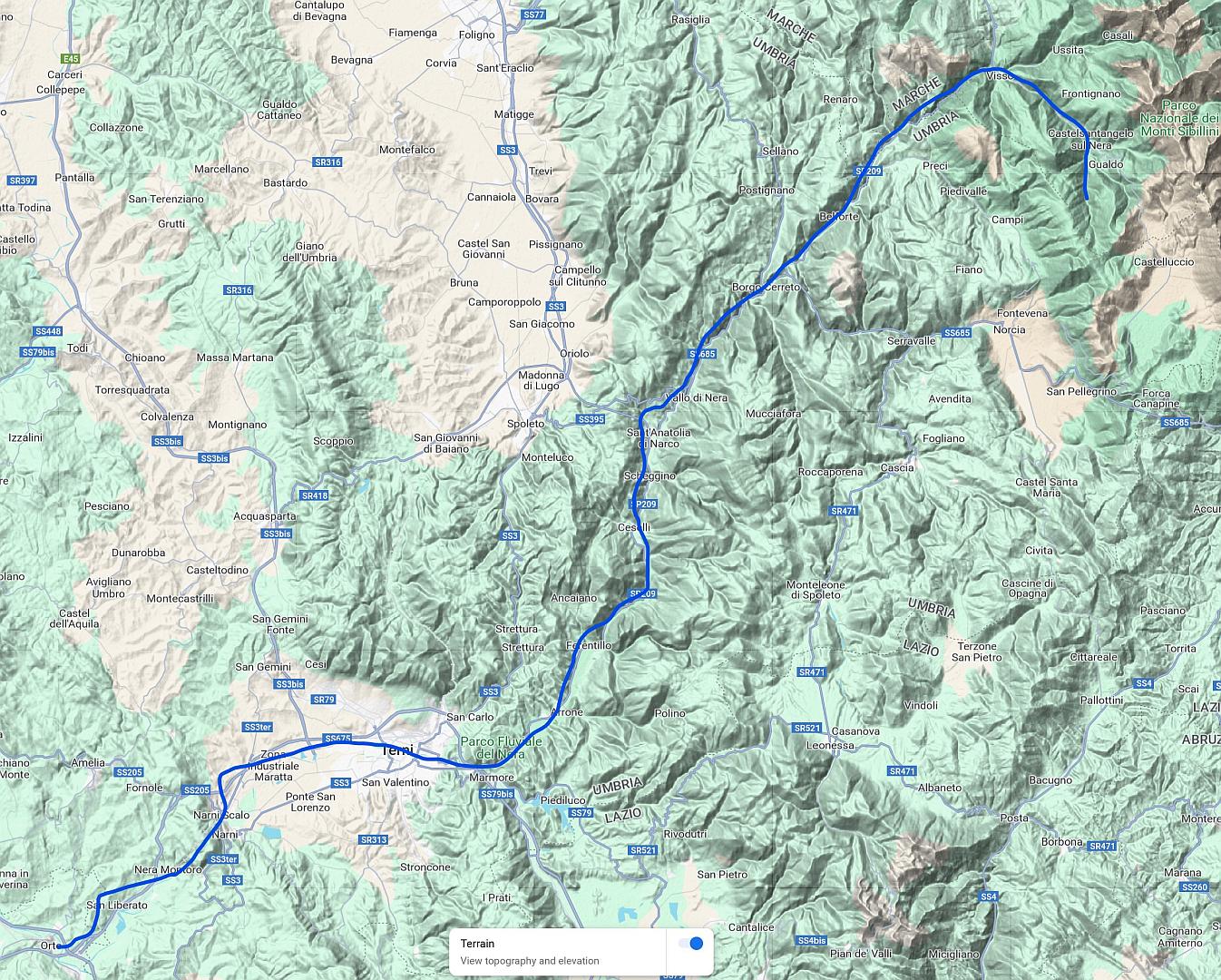

Who knows how old that story is, but it may have been a medieval invention because the first recorded appearance of the eagle in a Todi context was not until 1267. It is conventionally represented as clutching the stolen tablecloth in its talons, and it is often also seen sheltering two eaglets under its wings; these represent the towns of Terni and Amelia, which were subject to Todi for a period in the 13th Century, something of which modern Tuderti (Todi citizens) remain very proud.

Fanciful though it all is, I rather like the fact that the very first event recorded in Todi’s long story is… lunch.

Umbrians, not Etruscans

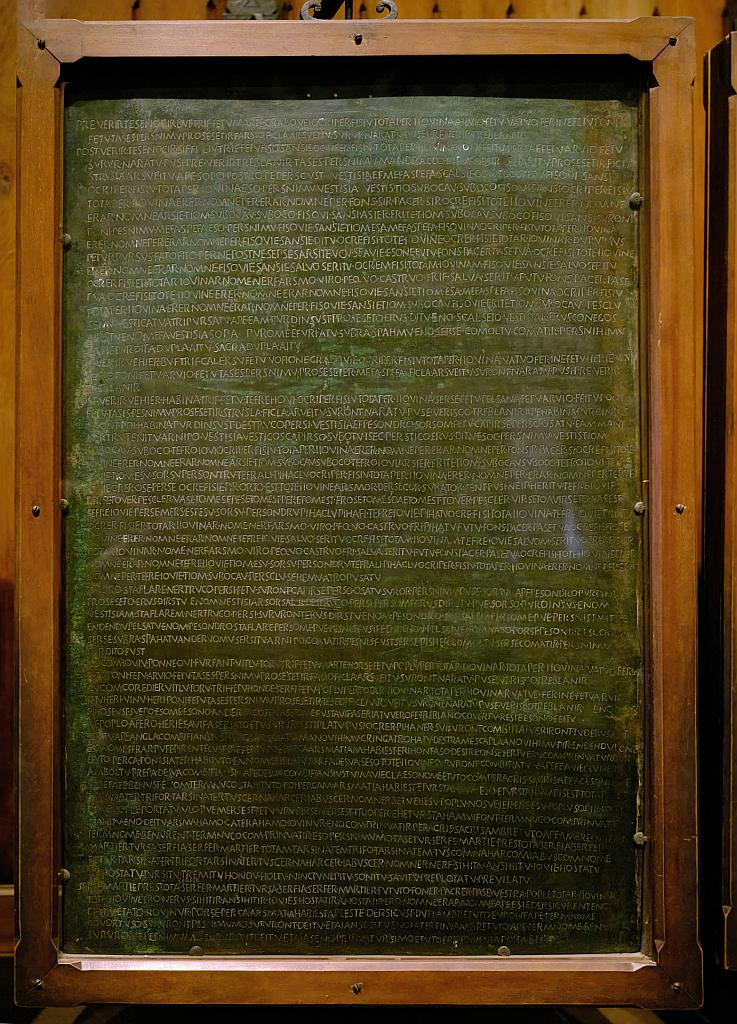

Turning from legend to things of which we are a bit more confident, it seems that in pre-Roman times the Tiber marked the boundary between the territories of the Etruscans and the Umbri, the latter – unlike the Etruscans – being an Indo-European people who spoke a language related to Latin. We actually have some examples of the ancient Umbrian language thanks to the improbable survival of the “Iguvine Tablets” of Gubbio, something else I intend to write about some day.

So Todi was a frontier town, and its very name – Latin Tuder, Umbrian Tutere, is said to come from a word meaning “border” (although whether that original word was Etruscan or Umbrian depends on which source you read). Away to the north on a clear day, in the 21st Century AD as in the 6th Century BC, one can see Perugia, then the easternmost of the twelve cities of the original Etruscan league, and the Tiber winds down from the north as a constant reminder of the boundary between the two territories.

It is common in Todi to refer to anything from the pre-Roman era as “Etruscan”, which makes a sort of sense, as everyone knows that the Etruscans came before the Romans. So for example there is a Via Mura Etrusche which leads down to the pre-Roman walls, and many guidebooks assert that Todi was Etruscan. But as we have seen, it is not strictly accurate – Todi was Umbrian, not Etruscan. A couple of years ago we went on a guided walk through Todi organised by the Fondo Ambiente Italiano (a bit like the UK’s National Trust). The guide was a pleasant and very knowledgeable chap who pointed out many interesting things, but he got quite agitated when someone (not us, fortunately) referred to the pre-Roman period in Todi as ”Etruscan”. It was obviously a sensitive subject for him.

So what were the ancient Umbri like, apart from not being Etruscan? Well, according to a 2020 genetic analysis, quite like the modern Umbrians, it seems. That’s quite interesting, because by and large Italians in most regions are anything but ethnically homogeneous – many waves of invasions, from the ancient Gauls to the Lombards and the Normans, have seen to that. Culturally, we can expect that the Umbrian inhabitants of Tutere would have shared a lot with their Etruscan neighbours – not just because of proximity but because they were at a similar stage of technological development.

Certainly, like most other Bronze Age cultures, they seemed to live in a society shaped by warfare. Apart from the obvious fact of having built their towns on defensible hills (whether or not eagles told them to), there are some other clues. The Iguvine Tablets from Gubbio make several references to enemies.

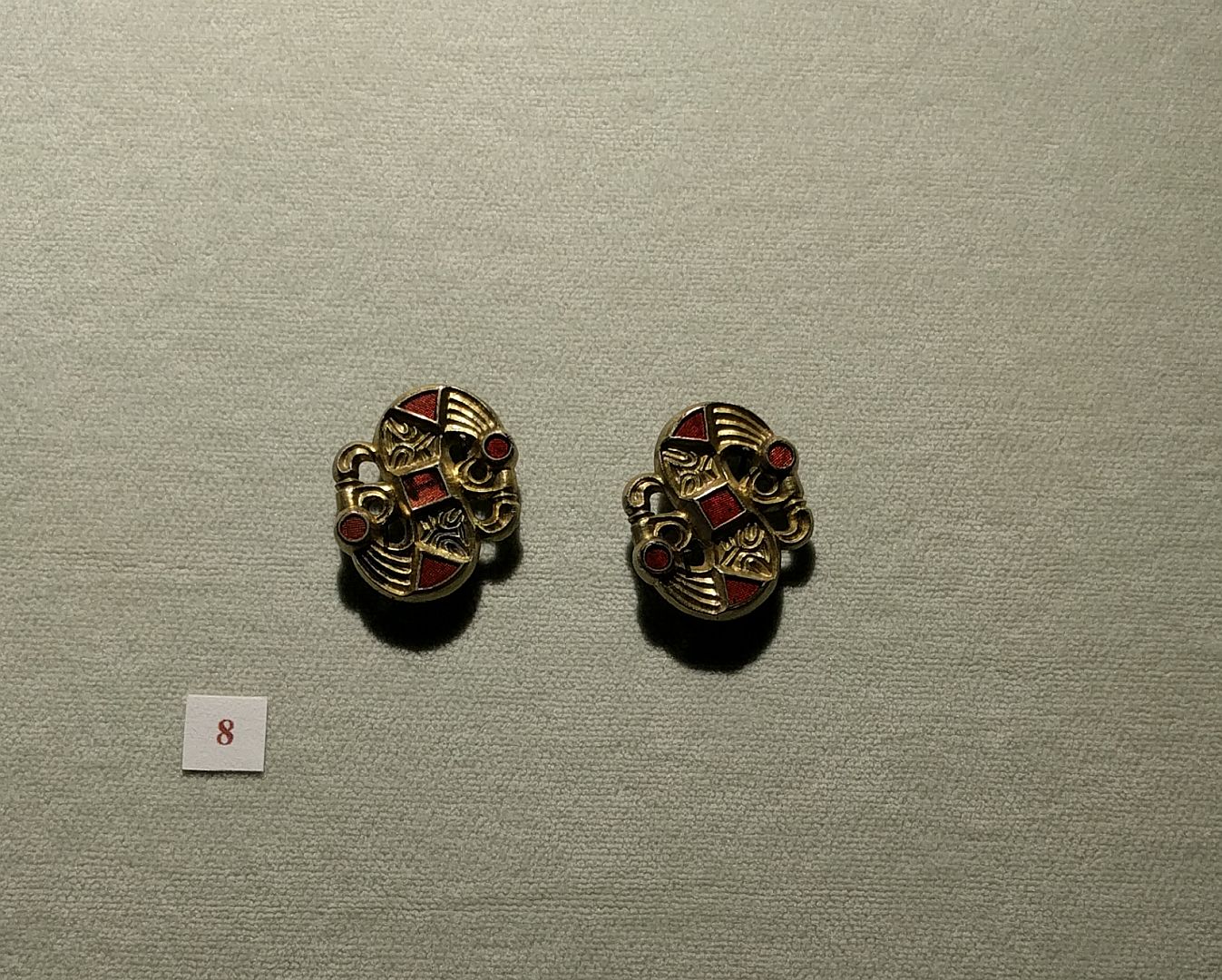

Bronze swords, spear tips and helmets also survive. Another clue is that in local museums you can see votive figures retrieved from sacred springs, where supplicants prayed to the gods for assistance. Some figures represent pregnant women, obviously offered in the hope of conceiving or of having a safe childbirth. But an awful lot of them clearly represent warriors, with plumed helmets and shields, and in aggressive stances. Not the sort of offering you would make if you were praying for a good harvest, but one you might make if you were hoping to come home alive from a battle in order to bring the harvest in. While most are tiny little figurines, the most famous and elaborate of such offerings is the so-called “Mars of Todi”.

This extraordinary life-size bronze statue, dated to the 5th or 4th Century BC, was dug up in 1835 at a place just outside Todi called Montesanto which at various times has been a monastery and a castle, and in ancient times was very likely some sort of religious precinct. Unfortunately for Todi, anything like that which came to light during the centuries of Papal domination went straight to the Vatican, which is where the Mars of Todi remains; what you can see in Todi’s Civic Museum is a facsimile made in the 1990s and paid for by a local citizens group. (That is one of the reasons why the local museum has such a comparatively poor showing: the other is what Italian historians call the “Napoleonic Despoliation”, when French troops methodically stripped northern and central Italy of the artworks that are now mostly in the Louvre. It’s strange – people go on and on about the Elgin Marbles, but no-one ever asks the French to give anything back. However I digress.)

The armoured figure, with (now missing) spear and helmet, was at first identified as a god of war, hence the name “Mars of Todi”. But modern scholars, pointing to the fact that the statue’s right hand probably held a libation bowl (the facsimile in my photograph is holding such a bowl, but that is not in the original), more plausibly suggest that this depicts a human warrior making an offering to the gods before battle. It was found under blocks of travertine stone, so it was deliberately buried. Whether it was made to be buried as an offering, or that was something that happened to it later, we will never know.

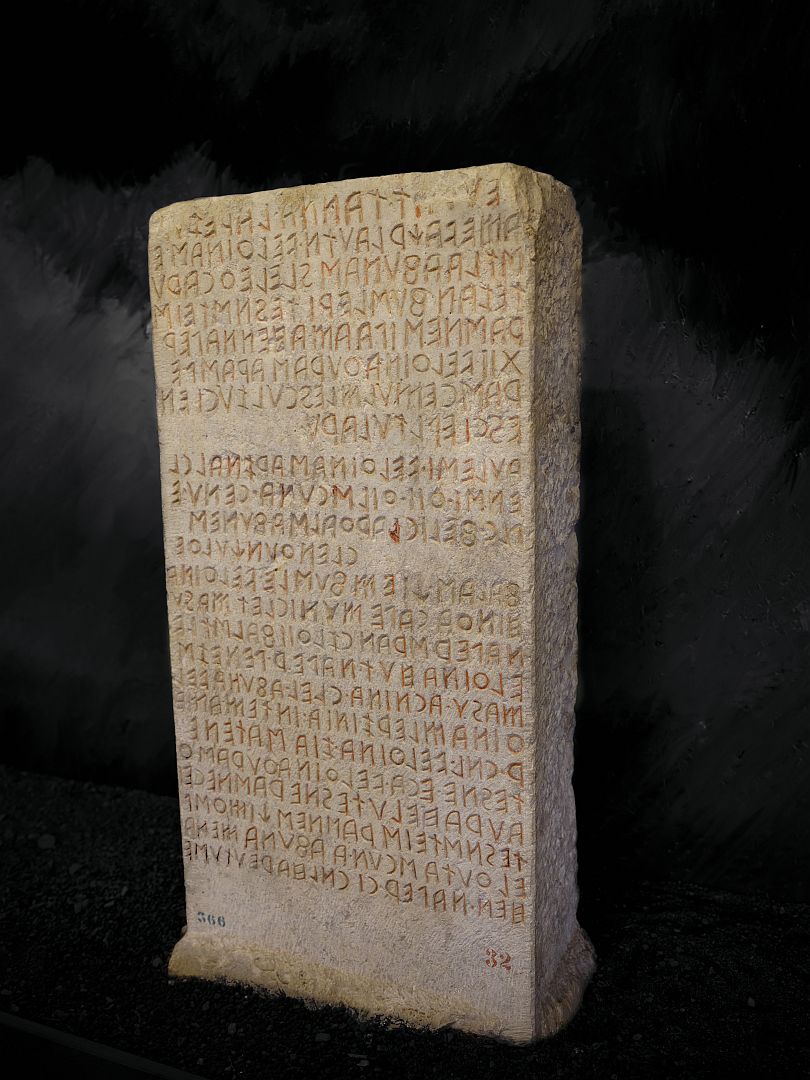

It is believed to have been made in the Etruscan city of Orvieto, a manufacturing centre for such bronzes, and it carries an inscription in Umbrian characters saying that it was a gift from someone called Ahal Trutitis. This is said to be a name of possible Celtic origin (the Celts, whom we now associate with Britain and Ireland, started out probably in central Europe and, as the Gauls, invaded Italy in about the 5th Century BC, not long before the statue was made). So someone, living in Todi and speaking Umbrian but perhaps of foreign ancestry, was wealthy enough to commission what must have been an extremely expensive artefact from Etruscan craftsmen, possibly to seek divine assistance in a war against someone. It is all rather tantalising.

It does tell us that the area was wealthy and that despite wars, societies traded with each other as they always have. Some of those trade links were surprisingly extended. On the southern slopes of Todi, below where you now see the Renaissance church of La Consolazione, an extensive pre-Roman necropolis or burial area was discovered in the 19th Century.

Most of the objects found here in the 19th Century were dispersed to collections elsewhere in Italy or overseas, but finds continue to be made. On the road which runs beside the south side of Todi’s medieval walls (Via Orvietana) is a rather ugly modern building which houses among other businesses a CONAD supermarket.

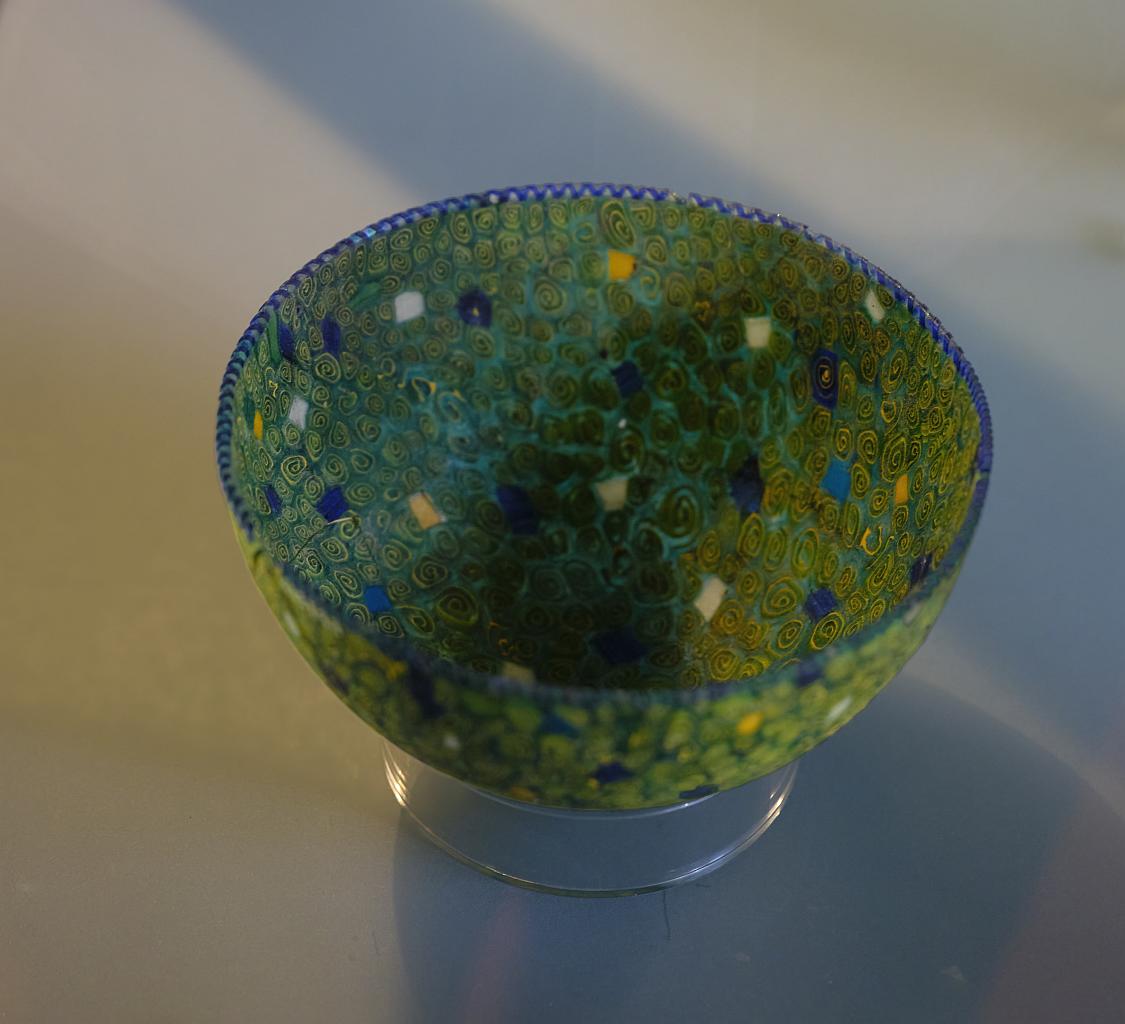

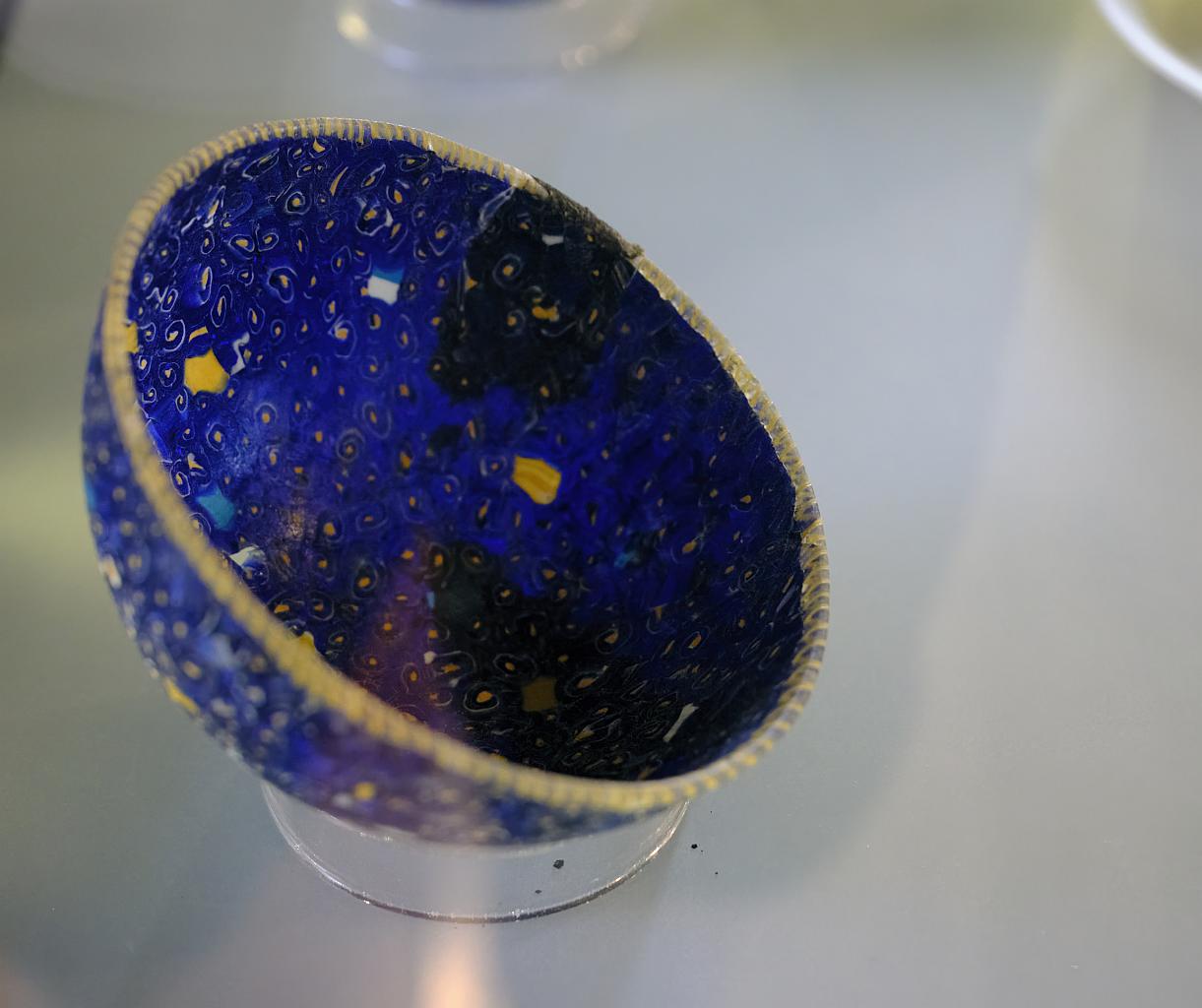

It was in 2007, while excavating for the foundations of this building, that they found pre-Roman graves containing many fine glass bowls of Alexandrian manufacture. These did not end up very far away and you can see some of them in an excellent display at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia.

The most obvious reminder of Todi’s pre-Roman era, however, is in the stones that make up the first of the town’s three circles of walls.

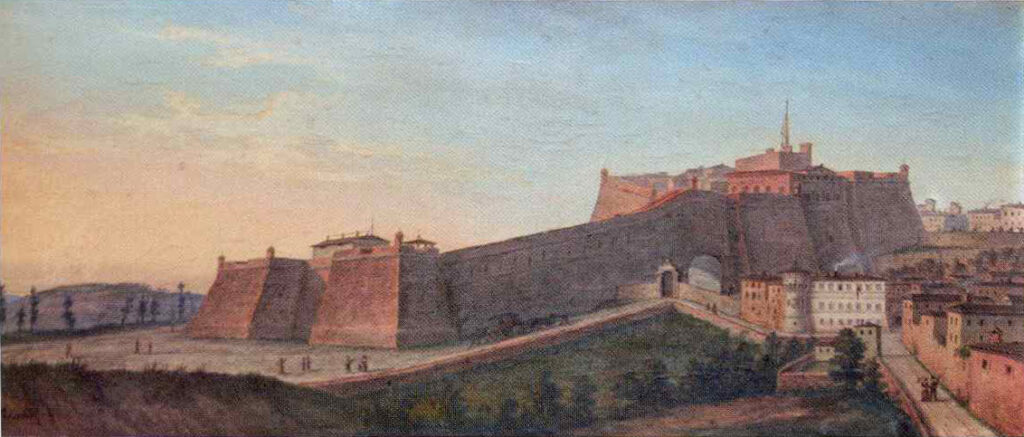

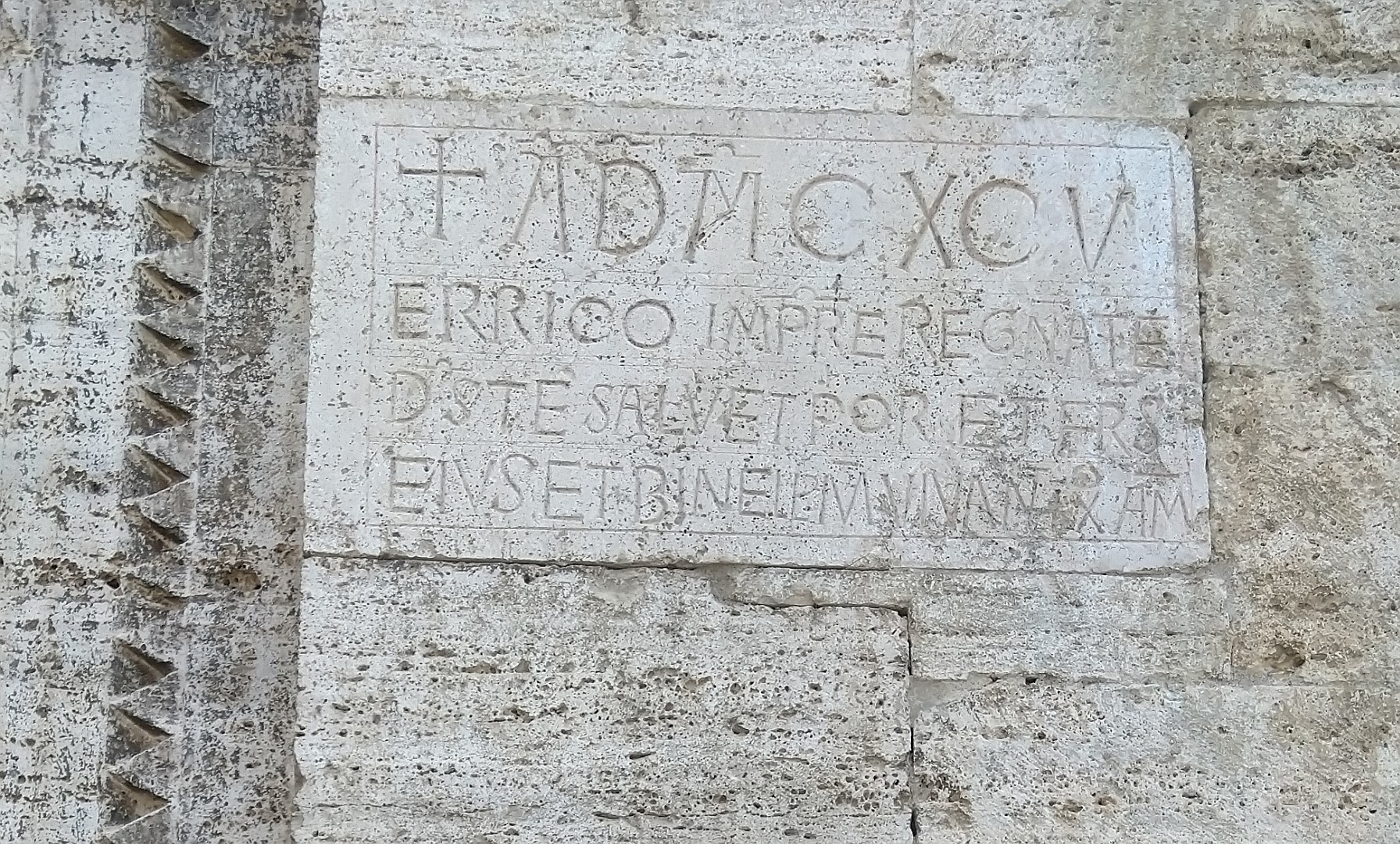

Todi’s first circle of walls dates, I understand, from the 6th or 5th Century BC, the second circle from the late Roman period around the time of the Gothic invasion of the 6th Century AD, and the third is a rank newcomer from around 1200. The two later circles are largely complete and I will probably write about them separately one day, but the first and most ancient wall is fragmentary – in many places it was incorporated into later walls and kept repaired.

My final example of pre-Roman stonework is easy to miss, and one that I would love to say that I discovered for myself, but in fact I first came across a picture of it in a book. It is just below the summit of Todi’s hill, leading up to what is now a park on the site of the medieval Rocca Albornoz.

On first glance this is a stone wall that could have been built as a single edifice, but on closer inspection there is a discontinuity – a diagonal line running up from the lower right to the left of the photograph. Below that line, the lower part is a ramp built in the pre-Roman period leading up to the top of the hill. One can imagine processions heading up to the summit, as part of ceremonies for whatever gods the Umbri worshipped. Above that line, less regular than the ancient original, older stones were re-used in late Roman or early medieval times to turn the ramp into a wall. Further above that, several hundred years later, there was built a Franciscan monastery which now contains the town library and a high school, in the cloister of which they put on concerts in summer. And so the life of the town continues, on the most ancient of foundations.

Sources

My qualifications for writing this are simply that I am interested, and that in walking around Todi with a camera I have learned to look for patterns in the stone and ask myself what stories they tell. The guided walk sponsored by FAI was a good source, as is the municipal museum and the explanatory texts in it, while the Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia is excellent and well worth a visit. There is a section on local history in the town library (in the old monastery above the pre-Roman ramp illustrated above). We have found a couple of books in Italian which deal mainly in later art and architecture but which refer peripherally to the ancient period. These are Todi, storica ed artistica, written in 1961 by Carlo Grondona and updated and republished in 2009 by his son Marco.

Another, dealing only with a couple of town districts, is TODI: i ‘rioni’ S. Prassede e S. Silvestro, Catalogo delle opere d’arte by Castrichini et al., 1999. One chapter by Lorena Battistoni deals with the Roman and Medieval history of the districts.

In English there is not so much. Umbria, A Cultural Guide by Ian Campbell Ross, 1996, from which I have quoted before, has a couple of chapters dealing with the prehistoric and pre-Roman ages in Umbria generally, although he concentrates more on Perugia and its Etruscan history than he does the Umbri.

A slim book called Todi Walking Tours, self-published in 2018 by Bernard Mansheim and Claudio Peri is available in local bookstores. It is a good way to make an initial acquaintance of the town, although some of the historical assertions in it are debatable.

I intend to follow this post in due course with one on Todi in the Roman era, of which there are more substantial remains than from the pre-Roman.