Perugia is a very ancient town. One very effective way to appreciate just how old is to look at a couple of remarkably-preserved town gates. This post adds a little more to the stories I have already told about Perugia.

Like many similar Central Italian towns, Perugia acquired more than one set of walls over the centuries. The original – inner – Etruscan walls had eight gates. Most of the surviving gates in the inner wall show their ancient origins in the form of Etrusco-Roman travertine blocks of the earlier structures at the base of later medieval gates.

However two gates have survived from antiquity in something like their original condition, and each tells quite an important story from Perugia’s past.

The Porta Marzia

In my post on The Buried Streets of Perugia I told the story of how Pope Paul III Farnese subdued the independently-minded Perugini, how he commissioned the architect Antonio Sangallo to build a huge fortress to dominate the town, and how Sangallo, in his haste to meet the papal deadlines, simply roofed over part of the old town to make a foundation for the fortress.

Had Sangallo carried out his task to the letter, one of the casualties – in addition to the Baglioni quarter of town – would have been a surviving Roman gate, the Porta Marzia (the gate of Mars) dating from the 3rd Century BC. Why it is called that is not known – plausible hypotheses include that there was a temple of Mars nearby, or that it was named after someone called Vibio Marso who paid for its construction.

It is certainly an elegant structure, as the photograph shows. Above the arch, and below the line of columns, you can see the inscription Augusta Perugia (explained below) and along the top you can see the inscription Colonia Vibia. This latter is a reference to Perugia having been granted the status of Ius Coloniae by the emperor Vibius Trebonianus Gallus who was a local boy, but whose reign only lasted from AD 251 to 253.

Whatever its origins, it remained in pretty good condition in the 16th Century. Unfortunately it stood in a place destined to be destroyed to make way for the foundations of Paul III’s fortress.

Paul is unlikely to have been too concerned about its loss – too many Medieval and Renaissance popes, looking at a well-preserved ancient building, would simply have ordered that any bronze be stripped and recast as cannon, and any marble be burned to make lime for cement. And if the loss of the Porta Marzia caused pain to the Perugians, then so much the better – as I discussed in the earlier article, Paul seems to have been the type to hold a grudge.

Fortunately Sangallo, like many architects of the era, had been taught to revere the architecture of antiquity and could not bring himself to destroy this particularly fine example. So he had it disassembled, moved and reassembled as a sort of façade on the outside of a bastion beneath the fortress. The distance moved was only about four metres, but it would still have been quite a lot of work. Posterity thanks you, Messer Antonio.

For the first few hundred years after the construction of the fortress, it seems that the Porta Marzia would not have been much more than a bit of decorative masonry. However now you can walk through it, into the old streets of the Baglioni quarter, then up an escalator into the centre of town.

The Porta Etrusca

Once you have come up the escalator into the centre, you need to walk the length of the old town from south to north, along the Corso Pietro Vannucci (the real name of the painter now known as Perugino).

You will pass a good many cafes, restaurants and chocolate shops, including the outlet for the “Perugina” chocolate company. You will also pass the complex of magnificent Gothic buildings that houses, among other things, the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, until you reach the duomo (cathedral).

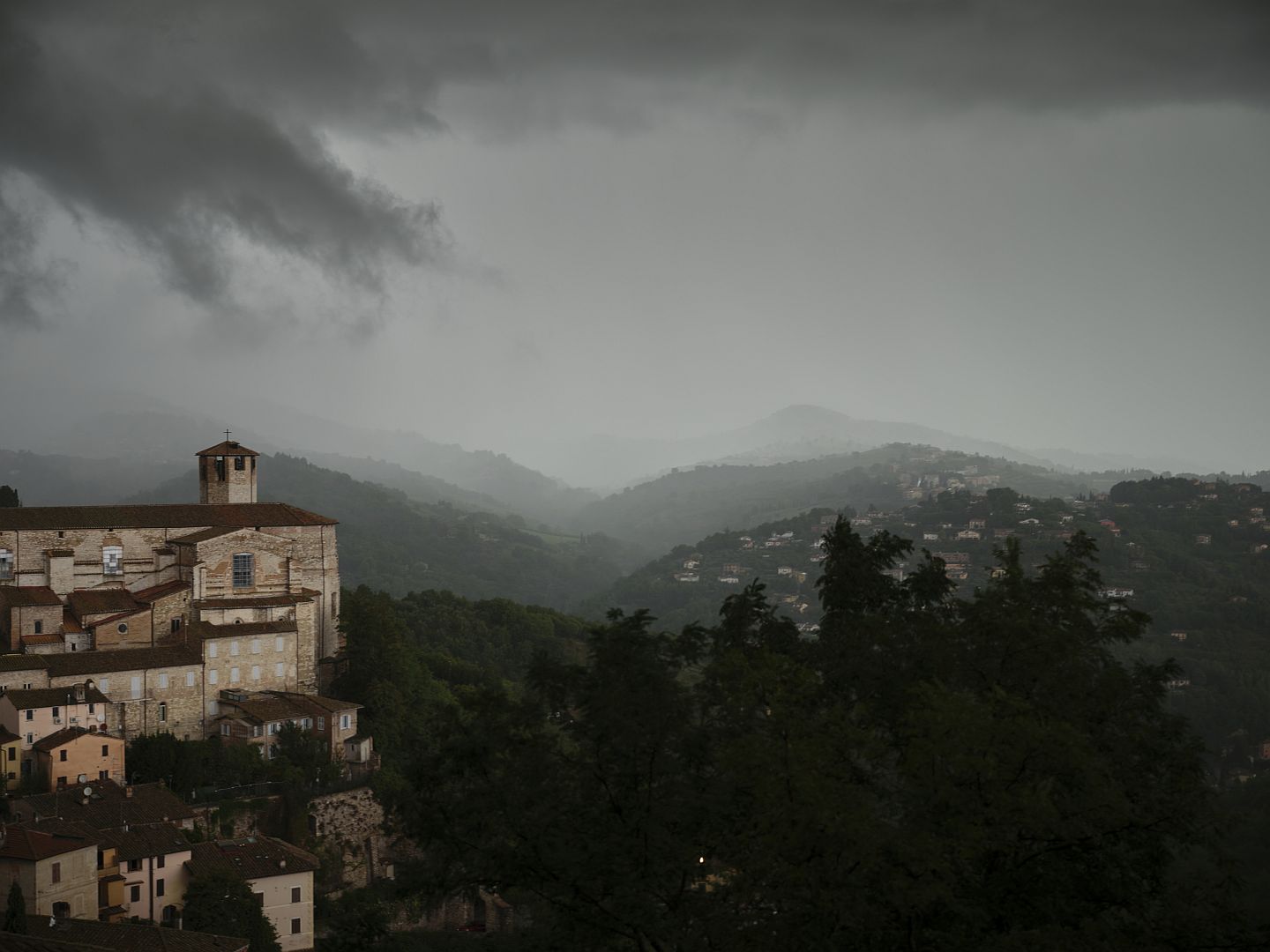

Once past the duomo, you can take the road to the left that heads downhill to the Porta Etrusca, but we would recommend taking the road uphill to the right that takes you there via the top of the walls, with an impressive view over hills to the north, beyond which is the Upper Tiber Valley. The photograph below shows that view shortly before a late summer thunderstorm broke.

Whichever way you go, you will eventually make your way down to the level of the road that runs around the outside of the inner set of walls. There, looking out over Perugia’s Università per Stranieri (University for Foreigners), you will find the Porta Etrusca.

This is a remarkable piece of architecture by any standard, not least for the various eras and events of Perugian history manifest in its stones.

Perugia (ancient Perusia) is first recorded as one of the 12 confederated Etruscan cities, at the north-eastern limit of the original Etruscan heartland on the border with the Umbri, a Latin people. Over time, as in other such centres, the Perugian Etruscan civilisation did not fall to Rome as such but became gradually Romanised to the point where it faded away. The local Etruscan noble families Latinised their names and became Roman aristocrats – the Emperor Vibius Trebonianus Gallus mentioned earlier came from such a family.

After the assassination of Julius Caesar, Perugia made the mistake of backing Mark Antony against Octavian, which saw the city captured and sacked in 40 BC. Octavian, as the Emperor Augustus, rebuilt the city and named it Perusia Augusta after himself.

The next time the Perugians really needed their city walls was during the Gothic Wars in the 6th Century AD, when the Ostrogoths under Totila eventually captured the city, killing Bishop Herculanus who had led the defence and negotiated the surrender. Now as San Ercolano and the city’s patron saint, he is presumably still keeping an eye on the place. Interestingly, the patron saint of Todi, a bit further south, was also that town’s bishop during the Gothic Wars.

During the Guelph-Ghibelline wars of the Middle Ages, and right up until the final defeat of Perugia by Paul III in the 16th Century, solid defences would presumably have been a high priority for the town’s governing council.

With all that in mind, let’s have a close-up look at the Porta Etrusca.

The massive unmortared travertine blocks that make up the lower part are Etruscan, around 2,300 years old, but looking fairly decent for their age. Then, just where the arch begins, the Etruscan blocks are replaced by more evenly-cut Roman masonry. And on the arch are carved the words Augusta Perusia, dating it to after the reconstruction of 40 BC.

Continuing upward, there is an ornamental frieze on which, if you look carefully, you will see the words Colonia Vibia, dating from after the granting of that title by Emperor Gallus in the 3rd Century.

Now let us move a bit further away to a spot from which we can appreciate the whole structure. The contrast between the rougher Etruscan stone and the more even Roman work is easier to see in this picture.

Look at the top right, where there is a section of quite poor-quality medieval stonework, looking as if it might have been done in a hurry. Was that a hasty repair as the Gothic army approached? No doubt there is an archaeologist somewhere who knows, but I have been unable to find a reference. If I ever do I will update this post.

And then finally at the top there is an elegant 16th-Century loggia. I find it remarkable that from here you can take in, at a single glance, a couple of thousand years of history (a bit more, if you include the electronic bus sign). I really enjoy bringing visitors here. Another attraction, a few metres up the street, is a shop called Augusta Perusia which sells excellent handmade chocolates. We approve of the name, and indeed the product.

2 Replies to “The Ancient Gates of Perugia”