The Rocca Paolina, or “Fortress of (Pope) Paul” was a symbol of oppression in Perugia for centuries. But its builder inadvertently saved a medieval streetscape for future generations.

One of the articles on this site that gets the highest number of views is Tough Guys in Art – the Baglioni of Perugia. Google moves in mysterious ways so I can’t really explain its popularity, but where I ended that article is where I propose to start this one.

To recap briefly, in the 15th and early 16th centuries the famously bellicose Perugians were ruled by a famously violent family, the Baglioni. When they were not slaughtering each other they managed to commission some fine works of art by artists like Perugino and Pinturicchio.

As I said at the end of that article, eventually the Baglioni fought each other to exhaustion. The Pope of the day (Paul III, formerly Cardinal Alessandro Farnese) saw his opportunity and took the town by force, beginning three hundred years of direct papal rule marked by economic, intellectual and artistic impoverishment.

Steep economic decline isn’t much fun for those experiencing it. But it does have the perverse benefit for more fortunate later generations of freezing a town or a landscape at the moment anyone stopped spending money on it. One reason the Cotswolds region in England is such a perfect jewel today is because the decline of the wool trade preserved it as it was. And so it was with Perugia, Todi, Spoleto and other scenic towns in Umbria – once all the revenues of the area were expropriated by Rome, things mostly just stopped.

Rubbing Salt into the Wound

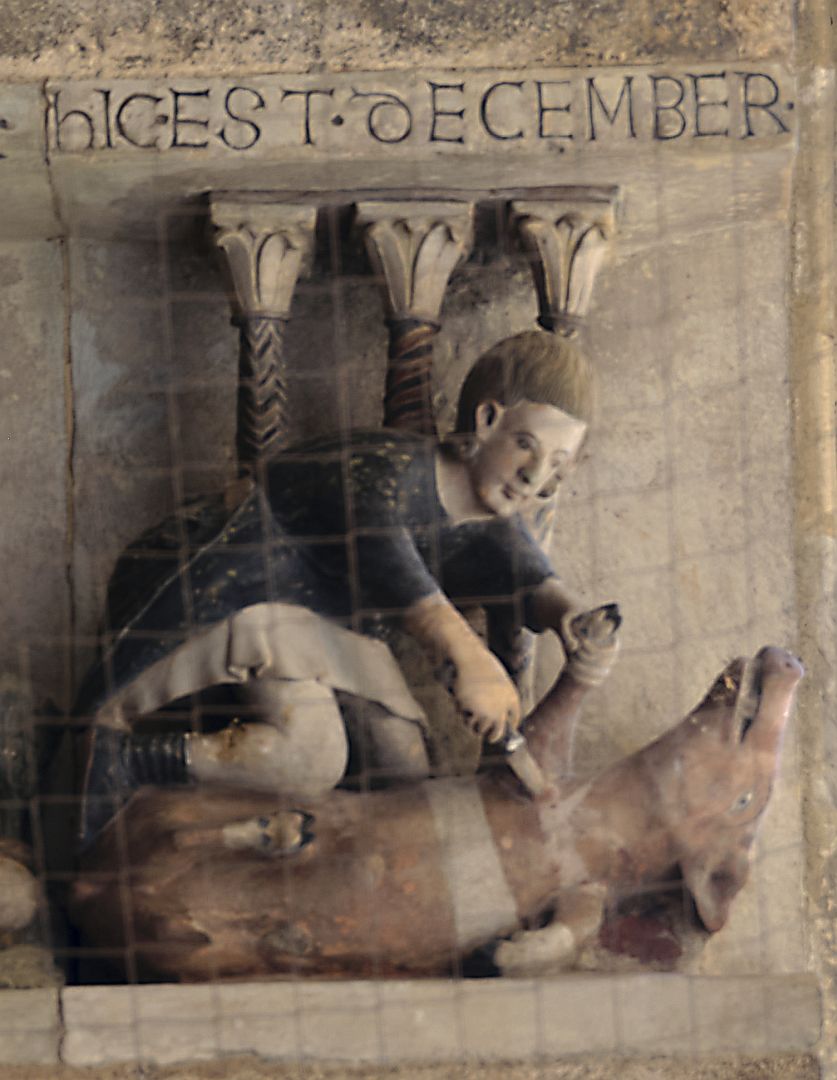

Even a Pope like Paul III needed to manufacture some sort of excuse to attack a city, and the casus belli he used was Perugia’s refusal to pay an extortionate salt tax. These days we think of salt as a seasoning that is bad for our blood pressure, but for most of European history access to salt was the difference between survival and starvation. It was what you used to preserve the remaining food (often a slaughtered pig) in winter to give yourself a meagre source of protein through the hungry months until spring. You also need it to make cheese, and to preserve vegetables in brine. Salt was one of the first goods to be traded in prehistory, and control of salt production brought power. In the Papal States the production of salt was a government monopoly, so when Paul III banned the importation of competing cheap good-quality salt from Tuscany, then jacked up the tax, and jacked it up again, he knew exactly what he was doing, and the effect it would have. These days we would call it economic warfare.

A brief aside on unsalted bread

By the way, it is very common to read that the reason modern Umbrians make such insipid-tasting unsalted bread is because it started as a protest against the tax. Umbrians are taught this in school and will repeat it to you earnestly. With all respect to my Umbrian friends, I find this implausible. Firstly because the amount of salt necessary to season a loaf of bread is considerably less than that needed to turn a pig into salami and ham or to preserve things in brine, so it would not have added all that much to the cost of the loaf, and would not have saved them much money. Secondly, they make equally horrible unsalted bread next door in Tuscany, which was not part of the Papal domains. Thirdly, there is some evidence that unsalted bread was a feature of the region long before Paul III came along – in a 12th-Century poem, the exiled Florentine Dante complains “how salty is another man’s bread”.

Another argument, that salted bread isn’t needed because Umbrian food is already salty enough, doesn’t stand up to analysis either. Food is salty everywhere in Italy. I think it is just that they make lousy bread in these parts, and being parochial Italians, have convinced themselves that their way of doing it is the right way. I live part of the time among the Umbrians and love them, but in this they are wrong. You can find an article by someone who is similarly sceptical here. (NB: In a tacit admission, most Umbrian bakers now sell salted bread. Just be sure to ask for “pane salato“. I may be imagining the slightly reproachful air with which they hand it over.)

The Conquest of Perugia

Anyway, the commander Paul III chose to subdue Perugia was Pierluigi Farnese, who just happened to be Paul’s illegitimate son (plenty of cardinals had mistresses in those days). Paul legitimised Pierluigi to allow him to become the head of the Farnese family, but apparently Pierluigi still had a chip on his shoulder from being mocked about his origins, creating an attitude problem which he tended to take out on defeated populations.

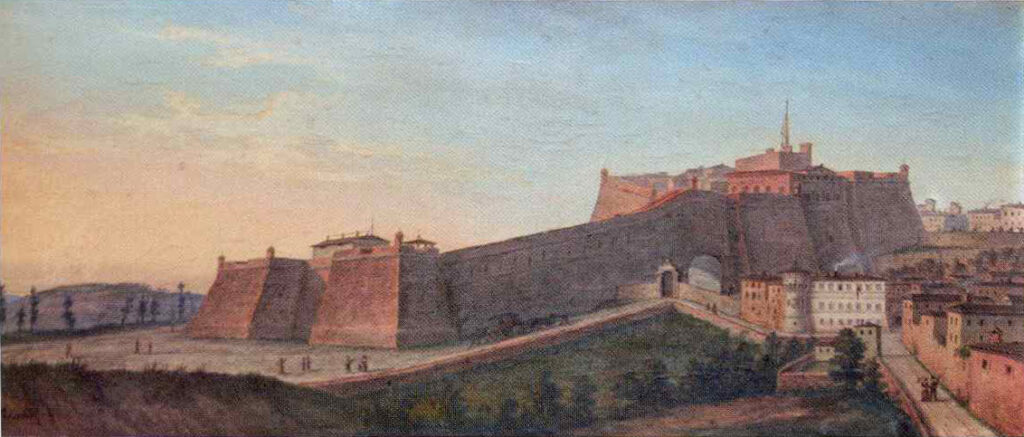

Once Perugia had submitted in 1540, Paul ordered the architect Antonio Sangallo to build a huge fortress at the southern end of the town. There were various factors at work here, both symbolic and practical. Firstly, the new Rocca would dominate the approaches to the town and the road from Rome. Secondly, it decisively moved the centre of power away from the northern end of town, where the lovely Gothic buildings that symbolised the city’s historic independence may still be seen. Illustrations show that the Rocca was huge, and did indeed make everything else in Perugia look insignificant.

Thirdly and probably most important to Paul (who seems to have been the sort to hold a grudge), building it there required the destruction of the quarter of the city where the Baglioni lived, and which had been their power base. It seems that Paul took a personal interest in the construction of the fortress, visiting Perugia several times during its construction to check on progress.

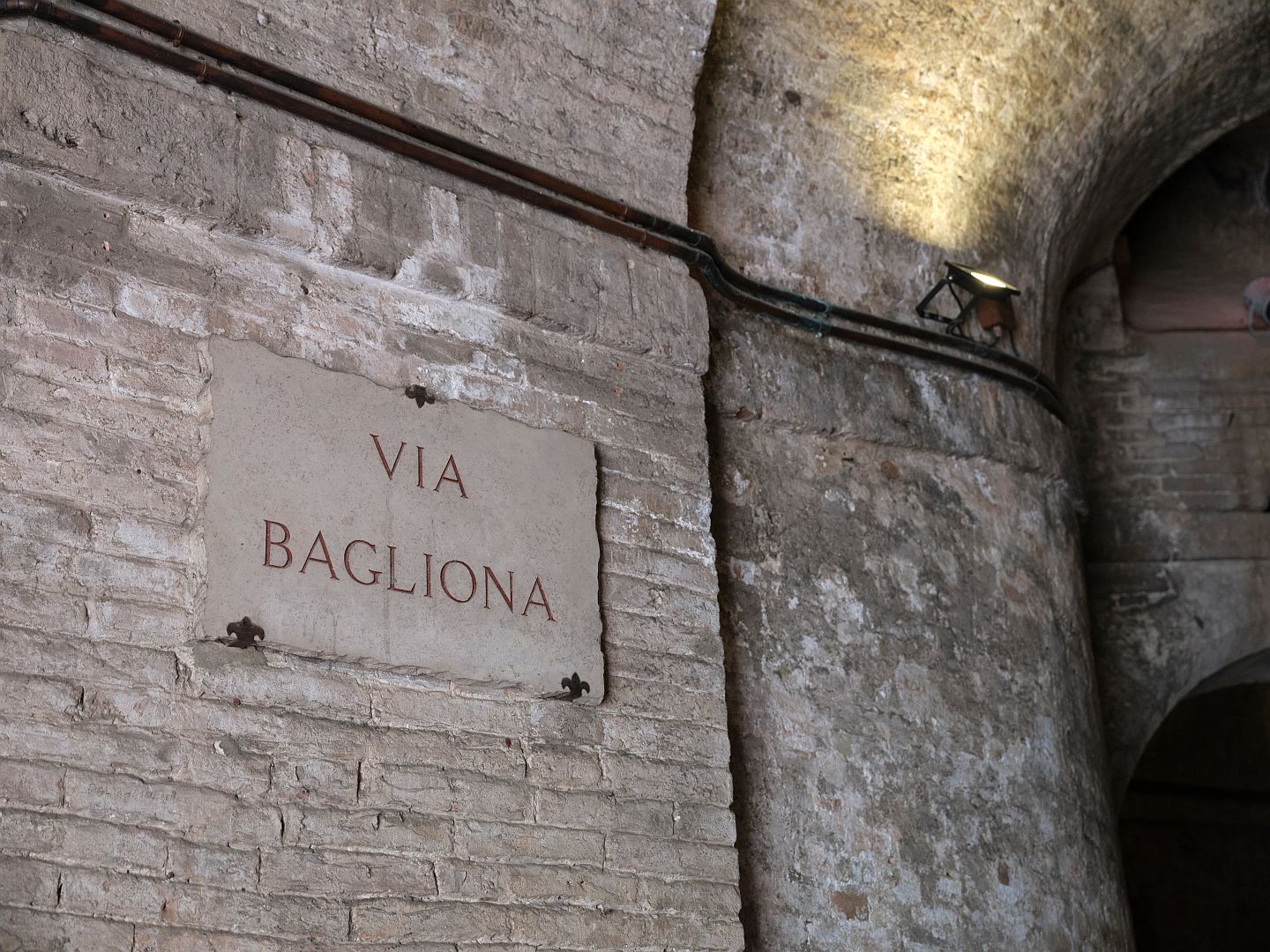

Sangallo was under pressure to proceed quickly, and fortunately for us he took an inspired short cut. Instead of demolishing the Baglioni quarter, and using the rubble and other landfill to create the foundations for the Rocca, he decided to use the intact stone buildings themselves as the foundations – using brick vaulting to fill in all the spaces between them. And so it was that streets, buildings and towers were preserved but hidden, the open sky was replaced by echoing brick vaults, and everything disappeared into darkness and silence for three hundred years.

Later Years

The Perugini were not particularly fond of their Rocca, not least since Paul placed an inscription on it explaining that the Rocca was put there to chastise them for their insubordination. Over time the government of the Papal States became more and more oppressive, and the Rocca was used as a political prison. It is therefore not surprising that it was partially destroyed by the Perugians during the Europe-wide uprisings of 1848, nor that it was subsequently rebuilt on the orders of Pope Pius IX as he swung from his initial reformist inclinations into the most obdurate reactionism.

Eventually in 1860 the Papal troops were expelled and Perugia became part of united Italy. I have read a story that afterwards the Perugians turned out with their hammers and chisels and demolished the Rocca Paolina by hand, stone by stone. I also read that as they did so, an old man would come along every day, and sit in silence watching them. When someone approached him and asked why, he said that he had spent much of his life in there as a political prisoner.

When the citizens had finished the demolition job, the reverse symbolism was completed when some fine Baroque-style palazzi were erected on the site, to house the city, provincial and regional governments (Perugia became the capital of the newly-created region of Umbria). So the locals had in a sense taken back control. They rubbed it in further by erecting an equestrian statue of King Victor Emmanuel II. The statue is as bombastic and overstated as its equivalents everywhere else in Italy, but in in this case the inscription “King Liberator” might have been genuinely felt.

Surrounding the seats of local government there are now some pleasant gardens, a statue of the artist Perugino, and a few bars, hotels and gelaterie. Just up the road is the outlet shop for the Perugina chocolate manufacturer. The casual visitor might be forgiven for missing the darker side of the site’s history altogether.

Meanwhile, beneath the ground, the old Baglioni quarter slept on, until excavations started in the 1930s which were completed in the 1960s. Thousands of people a day pass along those medieval streets, entering them from the escalators that take people up from the public car park in Piazza Partigiani. It is a very satisfying way to enter Perugia.

4 Replies to “The Buried Streets of Perugia”