The Mausoleum of Santa Costanza and the Church of Sant’Agnese are two remarkable buildings in Rome, giving visitors insights into the late imperial and early post-imperial eras. This post is the first of a series I have in mind, concentrating on some of the oldest surviving Christian buildings. (Note: you can click on the “Paleochristian” tag at the bottom of the article to see others in this series.)

Although I write about these things from a firmly secular point of view, I find the subject matter causes some algorithms to group my posts with genuinely religious articles, and this series will only make that more likely. So if you have come across this by that route then I apologise, but hope you like the pictures anyway.

I enjoy visiting so-called “paleochristian” churches, for all sorts of reasons. The term, meaning simply “old Christian” is a bit elastic, but it obviously includes anything built in the late imperial period, and ends – well, sometime after that, but certainly well before the end of the first millennium AD. So the magnificent 5th and 6th-Century buildings in Ravenna like San Vitale and the Arian Baptistry which I talked about in my post on Ravenna at the Fall of the Empire can probably be included.

What’s the attraction? Well firstly, if you are interested in the late Roman and early medieval periods, then any survival from those times is going to be worth a look, because frankly there isn’t all that much still around, and what there is will almost always be religious.

I suppose one of the main attractions is the sheer implausibility of the survival of these buildings. After all, the immediate post-Roman period saw some intensely destructive wars. However even without warfare, the general impoverishment of Italy and the decline of government administration meant that routine maintenance of public buildings almost certainly ceased. Even without earthquakes, some would just have fallen to bits.

Others were wantonly destroyed. As ancient Roman engineering knowledge faded away, old buildings tended to be seen as a source of materials for recycling, rather than something to be preserved. Being a consecrated church was some protection against such a fate, albeit not a perfect one.

Even if the main structure survived, subsequent generations sometimes destroyed the original interiors and exteriors. They may have censored artwork that was no longer considered theologically correct, as in the case of some of the Arian mosaics in Ravenna. More often it was simply that they felt like redecorating. This, alas, was the case for a great many churches in Rome in the Renaissance and Baroque eras. So, for example, tourists visiting the mighty basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore (to be the subject of a later post) will be greeted by the huge Baroque façade, and will need to look past a great deal of later stuff to see the magnificent 5th-Century mosaics in the apse.

In architecture as in bird-watching, relative rarity definitely adds to the thrill of discovery.

The Mausoleum of Santa Costanza

We will start, appropriately, in Rome, and with a building whose claims to antiquity are beyond argument. This is because it is a mausoleum probably built to house the tomb of one of the daughters of Constantine, the Emperor who was given credit for ceasing the persecution of Christianity and setting it on the way to becoming the established religion (it may actually have been his predecessor and rival Maxentius). That dates it to the 350s or thereabouts.

Constantine may or may not have formally converted to Christianity, but his formidable mother Helena and his two daughters definitely did. Constantine’s daughters – Constantina and another Helena – were both buried in this building, in magnificent porphyry sarcophagi that are now in the Vatican museum. There is a very plausible theory that the mausoleum was actually built for the younger sister Helena, who was married to the emperor Julian the Apostate, but tradition gives it to her sister Constantina, subsequently Italianised as Costanza.

It’s not clear that this particular Costanza was ever a canonised saint. Indeed contemporary accounts talk of a rather violent, vindictive and highly political person, whose second marriage was to the eastern sub-Emperor Gallus – not really saint material. It seems likely to me that at some stage she was conflated with another Costanza who was a 1st-Century martyr. The saintly virgin martyr and the tough-cookie empress were merged and a completely ahistorical life story was confected to suit this new hybrid character. If you do an online search for “Saint Constance” you will find modern documents referring to a pious unmarried virgin who was the daughter of the emperor and was cured of leprosy by a miracle. Obviously not true.

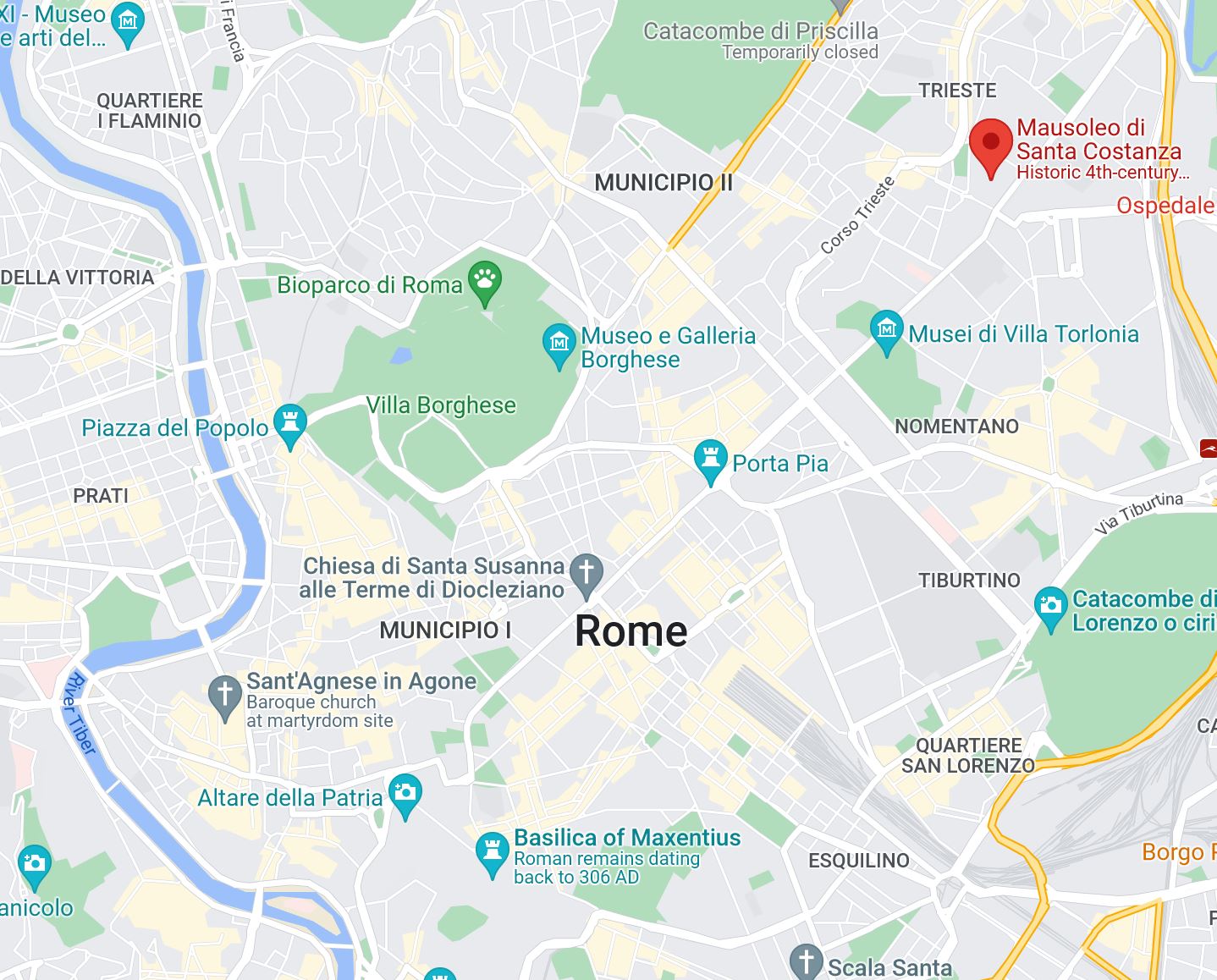

Be all that as it may, the building is well worth a visit. It is in the inner northern suburb called Nomentano, not far outside the Aurelian Walls of Rome, so in the 4th Century probably a settled area of villas and market gardens but with enough open land available to build this sort of thing. Roman law banned burials inside the walls, so it is in places like this that one sees classical tombs like those which line the Via Appia, and where Christian catacombs may be found, as we shall see later.

The Mausoleum is a fairly short walk from the Sant’Agnese/Annibaliano metro station. You can just walk in off the Via Nomentana, and suddenly you have left the roar and bustle of modern Rome and entered a quiet place that has been sleeping for 1700-odd years. If you have enough coins in your pocket and the meter is actually working, you can turn on lights to illuminate the interior. We have been there several times over the years, and each time we were struck by how few other visitors there were.

Like many of the most ancient religious buildings it is circular, rather than having the cross-shaped plan adopted in the Middle Ages. Its construction is concrete faced with brick, and in turn the bricks were apparently once covered with coloured stone, now lost. So it was probably quite imposing. The central area has a high dome, once covered in mosaics but unfortunately now decorated with a mediocre fresco from what looks like the 17th or 18th Century.

The real highlights are the mosaics covering the ceiling of the circular ambulatory vault which surrounds the central area. These are quite secular in their themes, suggesting that the mausoleum was not originally intended as a church, even though it was later consecrated. Indeed, several have a bucolic theme, with birds, flowers and fruit, amphorae of oil or wine, and a slightly bacchanalian one with grape vines, and cherubs gathering and pressing the grapes.

The panel shown below is interesting in that it contains pagan imagery, albeit by that stage perhaps considered decorative motifs rather than religious ones. The style is apparently characteristic of decorations in imperial palaces of the day, so quite appropriate for the daughter of one emperor and the wife of another. Nevertheless it shows that the later institutionalised hostility to pagan symbols (I guess we would call it “cancelling” today) was still some way off.

There are some Christian images: the lost mosaic inside the dome was apparently of biblical scenes, and around the ambulatory there are a couple of apses, with mosaics in a different style and perhaps of poorer quality than the secular ones. One shows “Christos Pantokrator”, or “Christ the ruler of all”. The other, below, shows a youthful, blond Christ giving a scroll representing divine law to Saints Peter and Paul.

It’s fascinating to see how some of the Christian iconography with which we are familiar from the Middle Ages and Renaissance had not yet become entrenched. Early representations of Christ often show him young, blond and sometimes clean-shaven. On the other hand the traditional representations of St Peter as white-haired and bearded, and St Paul as dark-haired and balding, as here, are very ancient.

Sant’Agnese Fuori le Mura

If you leave the Mausoleum of Santa Costanza and look to your left, you will see what looks like a park with some old walls sticking up out of the earth. The old walls are in fact the remains of a large basilica dedicated to Saint Agnes (Sant’Agnese), which predated the Mausoleum. Agnes is a saint whose martyrdom (with various miraculous embellishments) was said to have occurred during the Diocletian persecutions at the end of the 3rd Century. There was a catacomb here where Agnes was buried, and her cult quickly led to the building of the basilica, to which her supposed remains were transferred. In those early days “basilica” didn’t have its later meaning of a dedicated religious building, but was simply a large public building.

As I said earlier, in the post-imperial period sometimes buildings just fell to bits through neglect, and it seems that this is what happened to the original basilica of Sant’Agnese. So in the 7th Century Pope Honorius decided to replace the old basilica with a new church a short distance away. It is that which now stands beside the Mausoleum of Santa Costanza, and which holds the supposed bones of the Saint. The church is called Sant’Agnese Fuori le Mura (St Agnes Outside the Walls), which serves to distinguish it from the famous church of Sant’Agnese in Agone, the large (now very much baroque-style) church on the western side of the Piazza Navona in central Rome, built over the traditional site of the saint’s martyrdom.

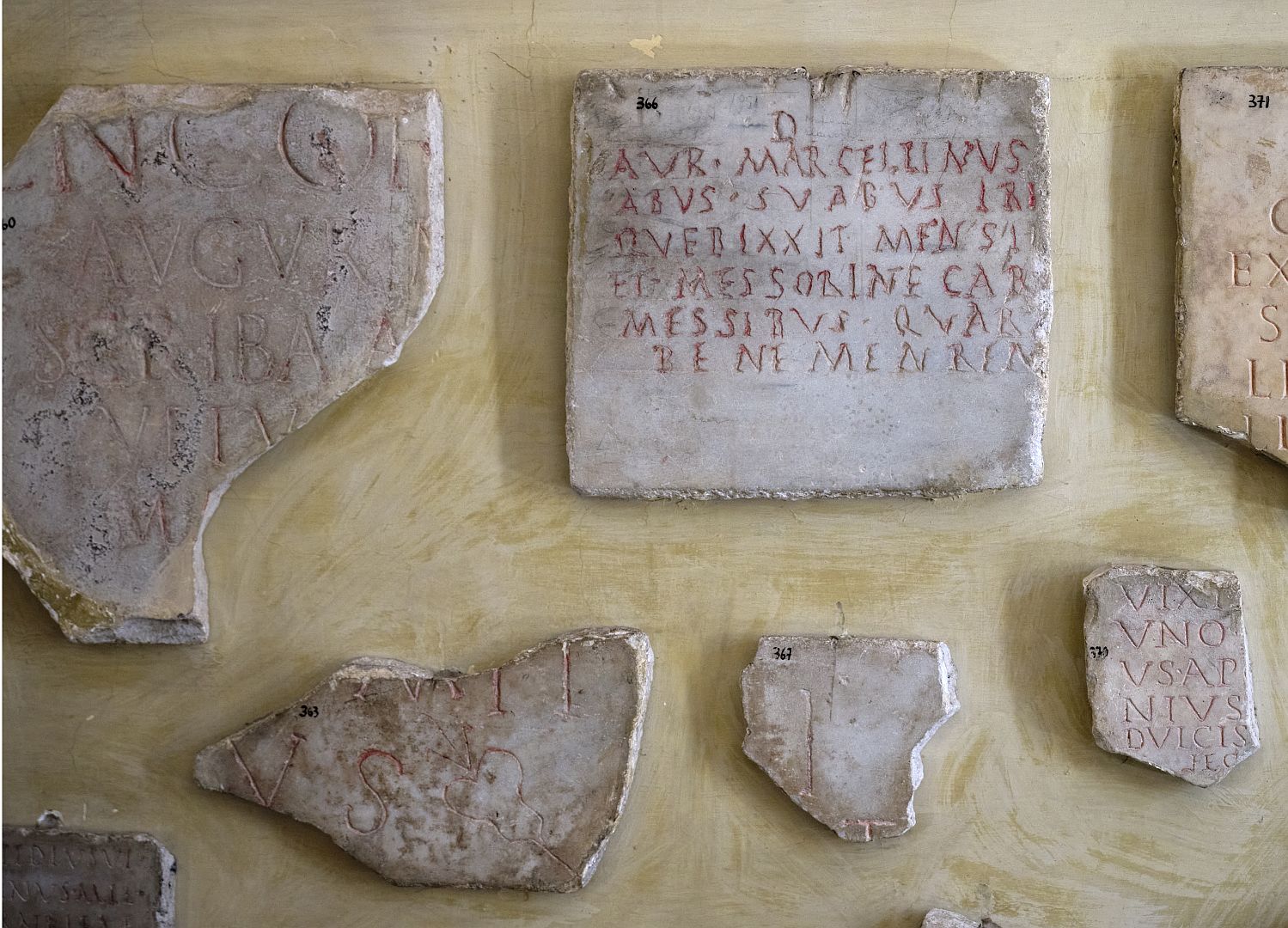

The approach to the church is through a pretty little garden, then down a long set of stairs, showing how the ground level has risen over the centuries. Lining the stairs is a display of fragments of funerary inscriptions from the site of the old basilica and the catacombs.

Once inside the church the layout is fairly conventional, with a nave, transepts and apse, suggesting that by the 600s the basic plan for churches had settled down. And as you will see in the photographs below, there is a good deal of decoration that is much more recent than the 7th Century, including the ceiling, the mosaic above the apse, and the canopy over the altar (ciborium, or baldacchino).

In fact the only major feature still in original 7th Century condition is the apse mosaic behind the altar, which shows Saint Agnes flanked by Pope Honorius (holding a model of the church) and another pope whose identity I have not been able to find. Since it dates from his time, we may suppose that the picture of Honorius is a likeness. Honorius is mostly known now for his unsuccessful attempts to resolve the long-running controversies about the nature of Christ, and whether Christ had separate divine and human energies. His efforts earned him little gratitude.

Agnes was a particularly popular saint, whose portfolios included being the patron of young girls. One of the traditions associated with her is that a young girl who prayed to St Agnes on the eve of her feast day would dream of her future husband. This is the subject of one of Keats’s finest poems, The Eve of St Agnes.

Due to her association with innocence and virginity – and also, one suspects, to a coincidental Latin pun on her name (agnus meaning “lamb”) – Sant’Agnese is often shown accompanied by lambs. One tradition still celebrated at the church is that on her feast day, two lambs are brought there to be blessed by the Pope. When the lambs are later shorn, the wool is used to weave the pallia, white bands worn around the neck, which are presented to newly-appointed bishops.

The area which includes the Mausoleum of Santa Costanza, the church of Sant’Agnese, the archaeological remains of the basilica and – incongruously – the Sant’Agnese Tennis Club covers a large urban block, and you can still visit the catacombs underneath, although we have yet to do so.

The last couple of times we have visited, it was noisy, chaotic and very hot outside. Inside both buildings it was cool and quiet, and the cherubs and saints looked down benignly on the few visitors that had found their way into the shadows, just as they would have done for over fourteen hundred years.

4 Replies to “Paleochristian Churches (part one) – Santa Costanza and Sant’Agnese”