Ancient Sardinia is something you cannot avoid – the remnants are everywhere and tell a complicated and fascinating story. Welcome to the second post based on material from a visit to Sardinia in May 2025. The first contained a general introduction and a series of photographs taken at the spectacular Festa di Sant’Efisio. In this one I propose to talk a bit about the many ancient remains to be seen, and to try and put them in a bit of historical context. I’m not an expert – just a historical dilettante with a camera.

Nuraghi

And what a lot of ancient things there are to photograph, especially the round towers called nuraghi, which gave their name to the “Nuragic” culture which lasted about a thousand years from the mid-Bronze Age into the Iron Age. The first time we got an opportunity to stop and look at a nuraghe I was very excited and walked briskly for about 20 minutes up a steep path for the privilege. By the next day we had seen so many that we only stopped if they were in particularly attractive settings, or they were in recognised archaeological sites that we intended to visit. After a week or so we had almost ceased to notice them. Apparently around 7,000 remain of an estimated 10,000, and Sardinia is not that big, so it is hardly surprising that you keep coming across them.

We noticed that many or most nuraghi bore the names of Christian saints. I didn’t read anything that said they were ever used as churches (although who can say what happened in early medieval times). But if a nuraghe was associated with a saint then perhaps they were considered to come under the that saint’s protection, and maybe that is why so many survive, at least partially. No doubt there are scholars who can answer that.

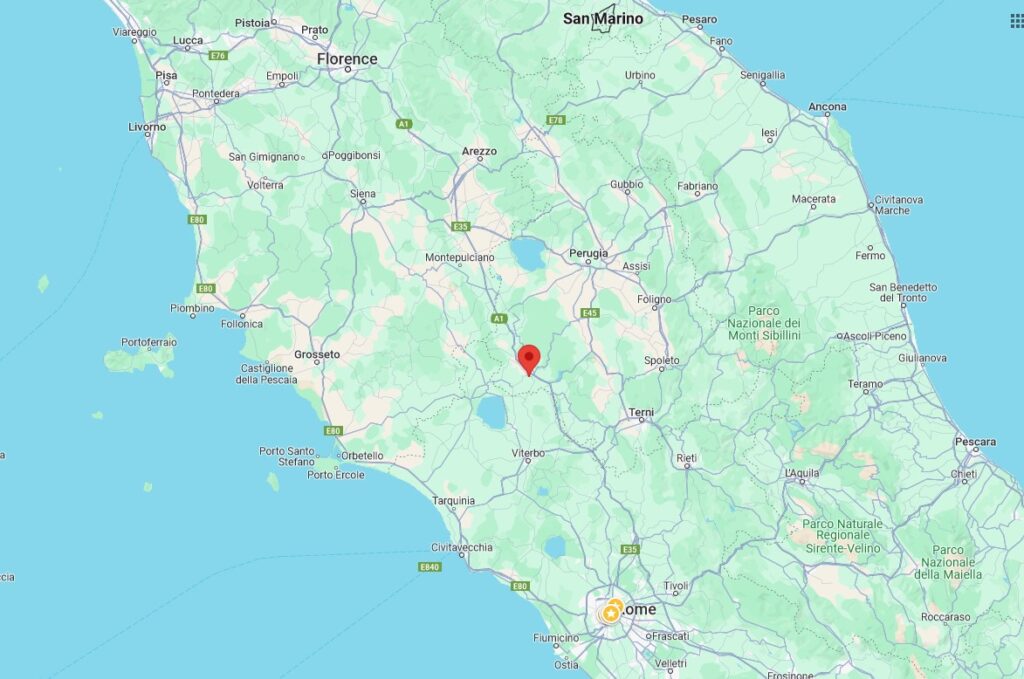

But let us step back a bit and try and put the Nuragic culture in context. Signs of human habitation in Sardinia date back to palaeolithic times, including temples and Stonehenge-style dolmens. But it was in the Bronze Age that signs of a distinctive, thriving and wealthy culture start to appear.

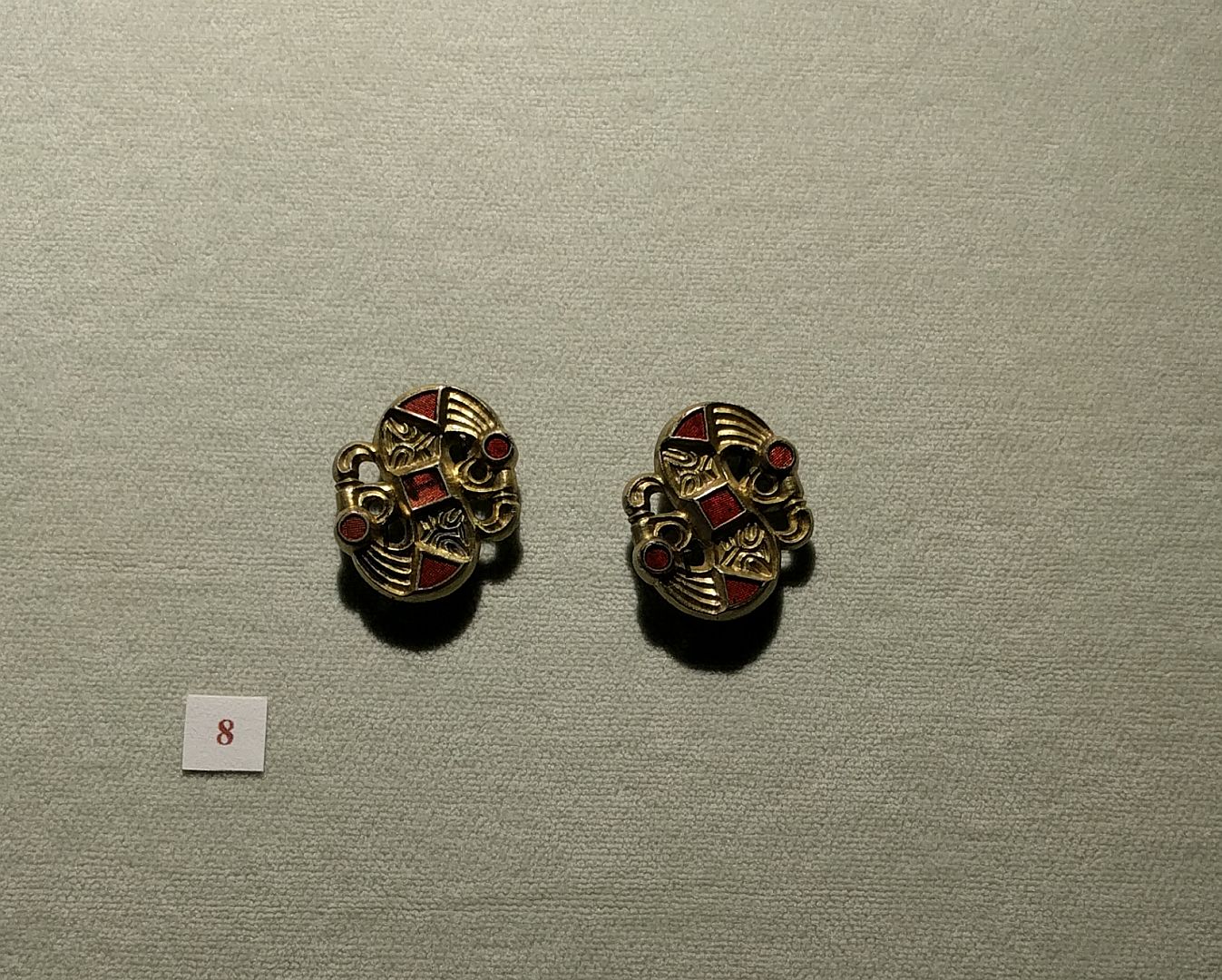

I mentioned briefly in the earlier article how Sardinia is geologically different from mainland Italy. One feature of that geology that it was rich in minerals that were less common elsewhere. These included silver, tin and copper – the latter two of course being the constituents of bronze. So the Sards had things to trade, and some artefacts from Mycenaean Greece have been found in Sardinia. Wealth means the emergence of a hierarchical society, included priestly and warrior classes.

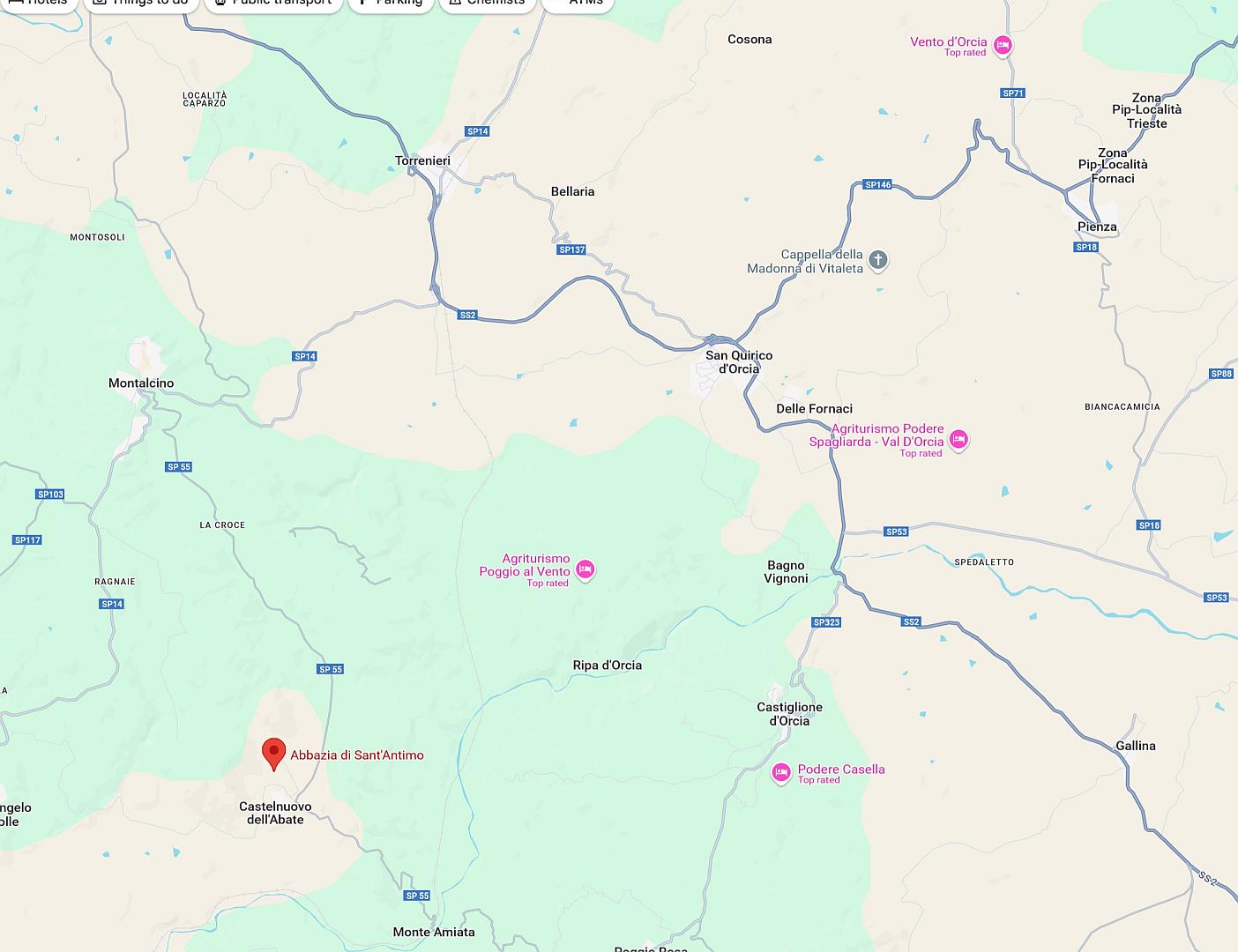

Most nuraghi are single round towers, but some major ones, described as palaces, were complexes of towers. Our guide book recommended one such, called Santu Antine, near the town of Torralba, so we paid it a visit.

Not only is Santu Antine bigger than the average, but it is surrounded by the remains of a couple of dozen houses, so it must have been a substantial community. For something that is about four thousand years old, and of drystone construction (ie. made without mortar) it is in very good condition. What is even more remarkable is that you can access the internal chambers and climb up the narrow staircase that winds up inside the walls. Rather than an empty cylinder with levels separated by wooden floors, the nuraghi were actually more like a series of domed stone chambers on top of each other, so very robust and hence still largely intact. The timescales involved challenge the imagination. Santu Antine has been abandoned for two thousand years, but was continuously inhabited for fifteen hundred years before that.

Like every nuraghe we saw, the upper part was missing. The technique of building them was that as the tower got higher, the basalt blocks of which it was made got smaller and lighter. This presumably made the upper stones easier to scavenge for reuse in other buildings. We certainly saw a few churches that had what looked like nuraghi stones in the walls.

Archaeologists say that the tops of the towers would have supported wooden platforms, and there was an illustration at the Santu Antine site with a hypothetical reconstruction, suggesting that the original building would have been quite a lot taller, and more sophisticated.

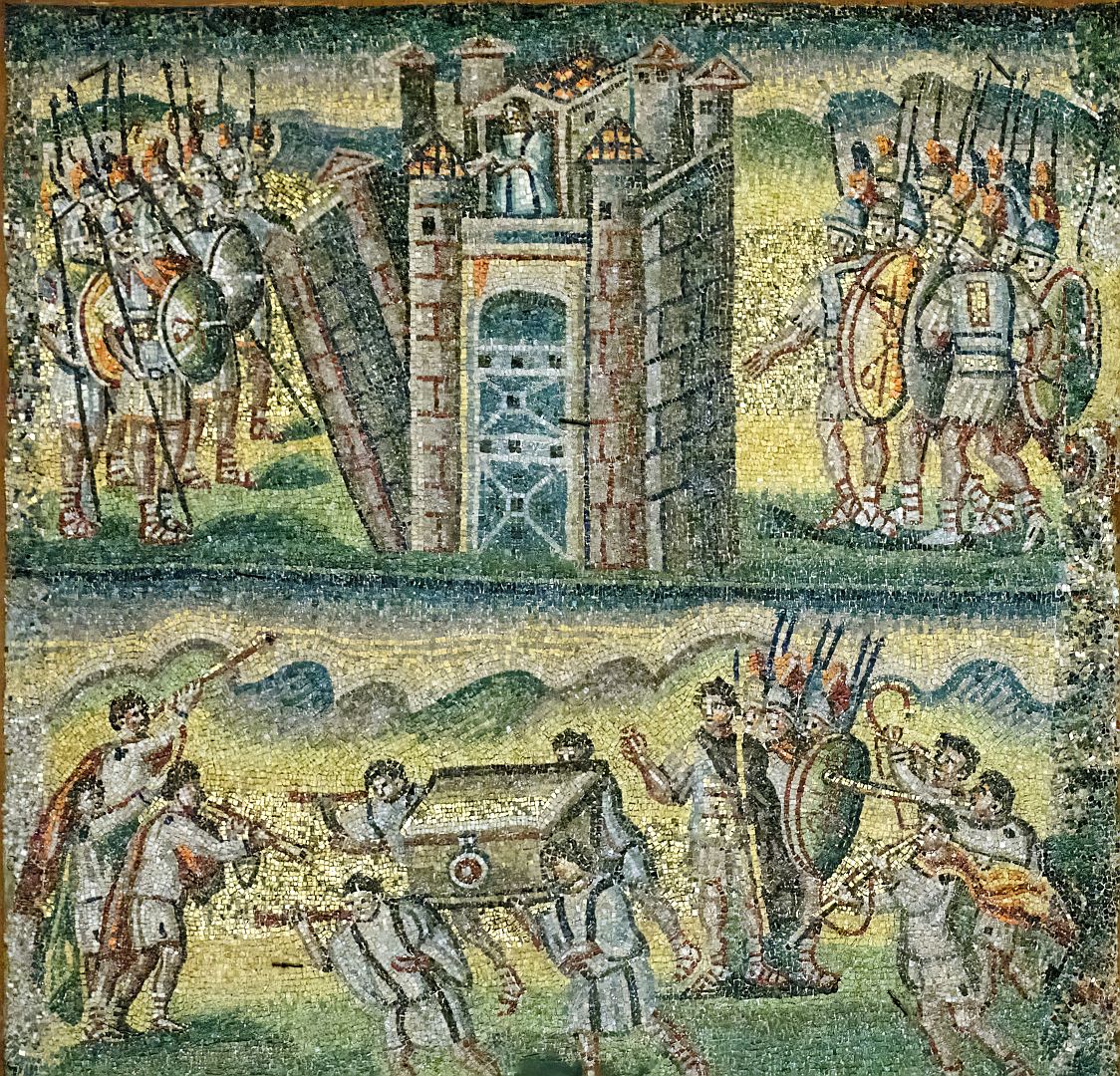

In the ticket office we downloaded an audio guide to the site, which was interesting, although it was a bit revisionist – trying to argue that because there was evidence of trade between Nuragic centres, the society was more peaceful than previous historians thought. We thought this a case of projecting 21st-Century AD attitudes onto the 19th Century BC. Firstly, trade and conflict have never been mutually exclusive states of society. Secondly, most European Bronze Age cultures were warlike; we know that not only from surviving artefacts such as weapons and figurines of armed men, but also because population increase led to competition for resources such as agricultural land and cattle (many of the heroic battles of the archaic age, celebrated in legend, might have been just cattle raids). And finally there is the practical aspect. There is a lot of work in building a strong tower out of large basalt blocks. It is not something you would do simply in order to enjoy the view from the top.

The price of the ticket to visit Santu Antime includes entry to the modest museum in nearby Torralba – probably not worth a visit otherwise, but since we’d already paid for it we went along.

Colonies and Empire

Mediterranean trade in the second millennium BC was surprisingly extensive. You can’t have a Bronze Age without bronze, which is an alloy of copper and tin, and the Phoenicians famously went as far as Cornwall in search of the latter. So in due course the Phoenicians established trading posts on the Sardinian coast, which in time became towns which were governed by the colonists, but where most of the population were native Sards. A bit like places such as Singapore and Hong Kong in the 19th Century, I suppose.

In time the Phoenicians were replaced by Carthaginians (Carthage was itself a Phoenician colony), and after the Punic Wars the Romans replaced the Carthaginians. Being Romans, they brought the place more formally into imperial administration, although not without some local revolts from Carthaginian remnants.

Even though all of Sardinia was nominally part of the empire, the central parts remained essentially ungoverned. These days the region is called the Barbagia, a name which supposedly derives from a rude remark by the Roman orator Cicero, who described it as being inhabited by barbarians. The term is now a badge of pride for the locals, referring to their independence from central government rule over many centuries. And one can see why. Although the mountains are not enormously high they are very steep and spiky – a punitive military force would have had great difficulty catching up with locals who knew the terrain. Until the mid-19th Century most of the various dynasties that claimed ownership of Sardinia took their lead from the Romans and left the people of the interior largely to their own devices as long as they didn’t do anything completely outrageous – small local disputes were OK.

I read somewhere a suggestion that the inhabitants of the Barbagia retained pagan or semi-pagan beliefs into the Middle Ages, which is plausible, I suppose.

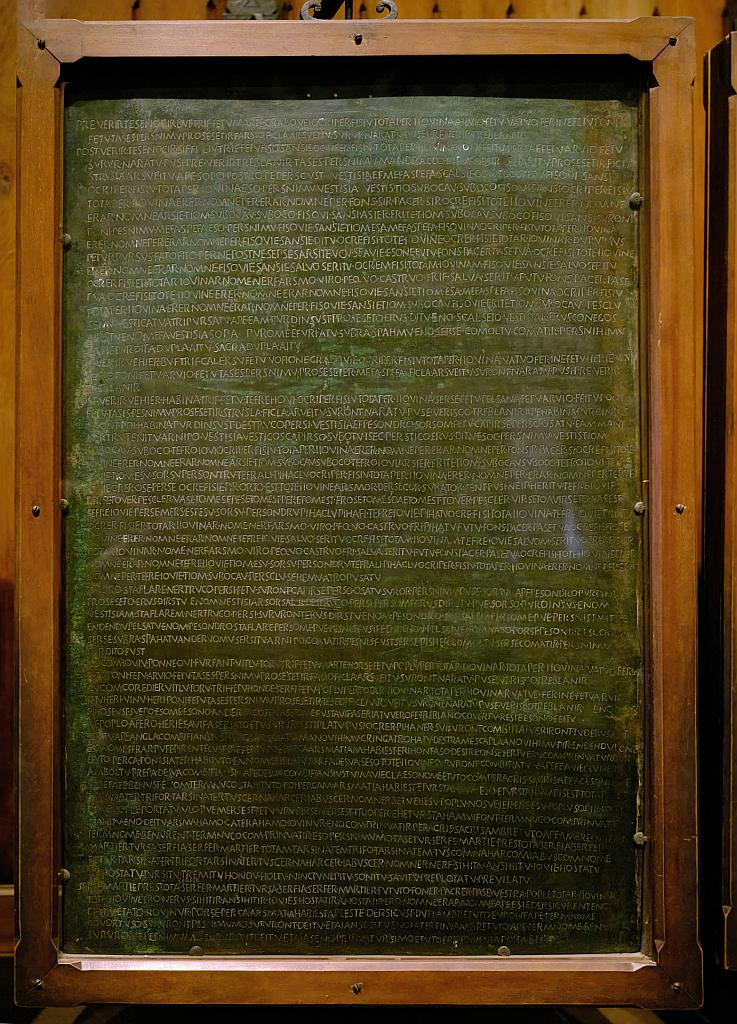

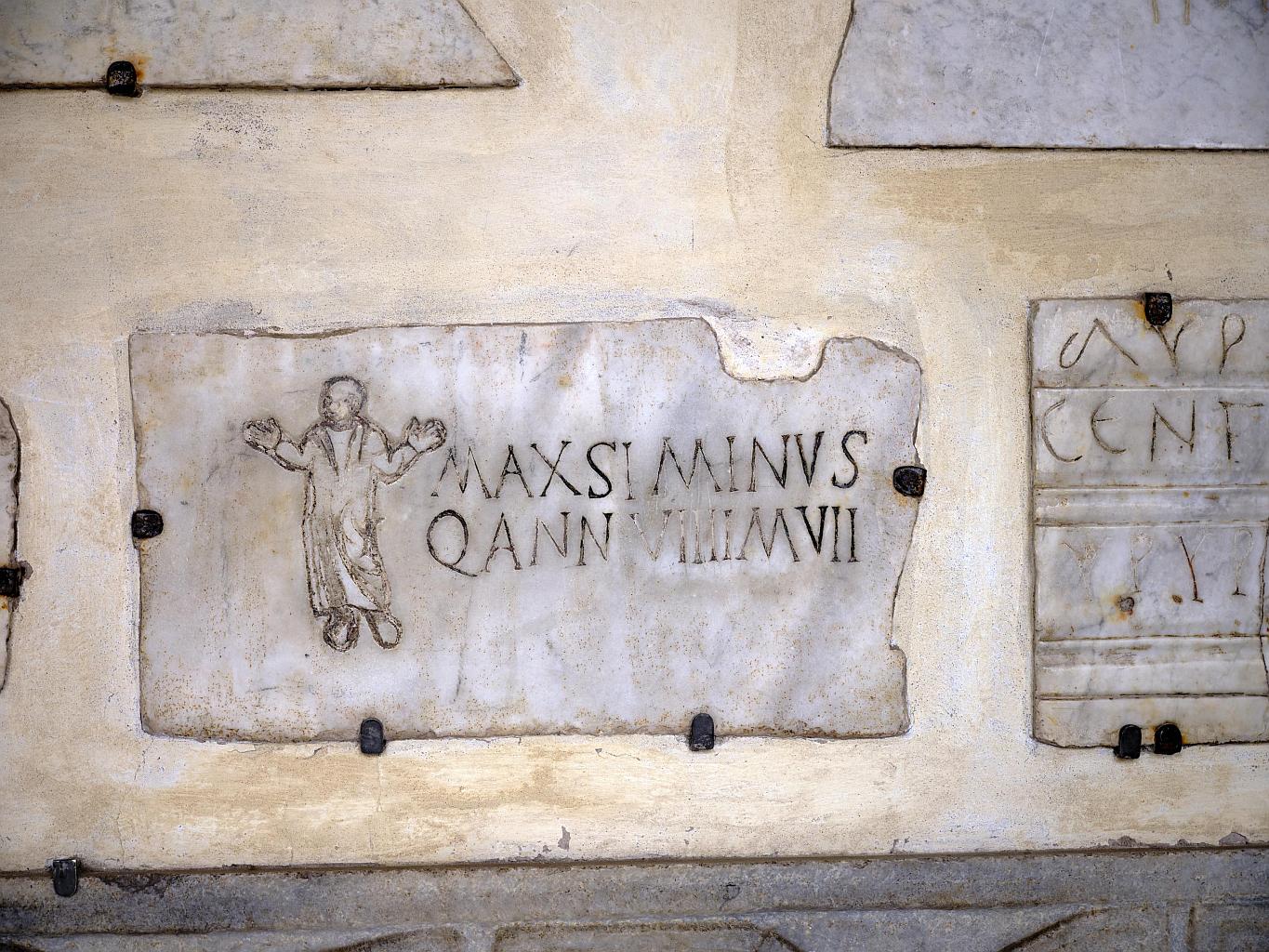

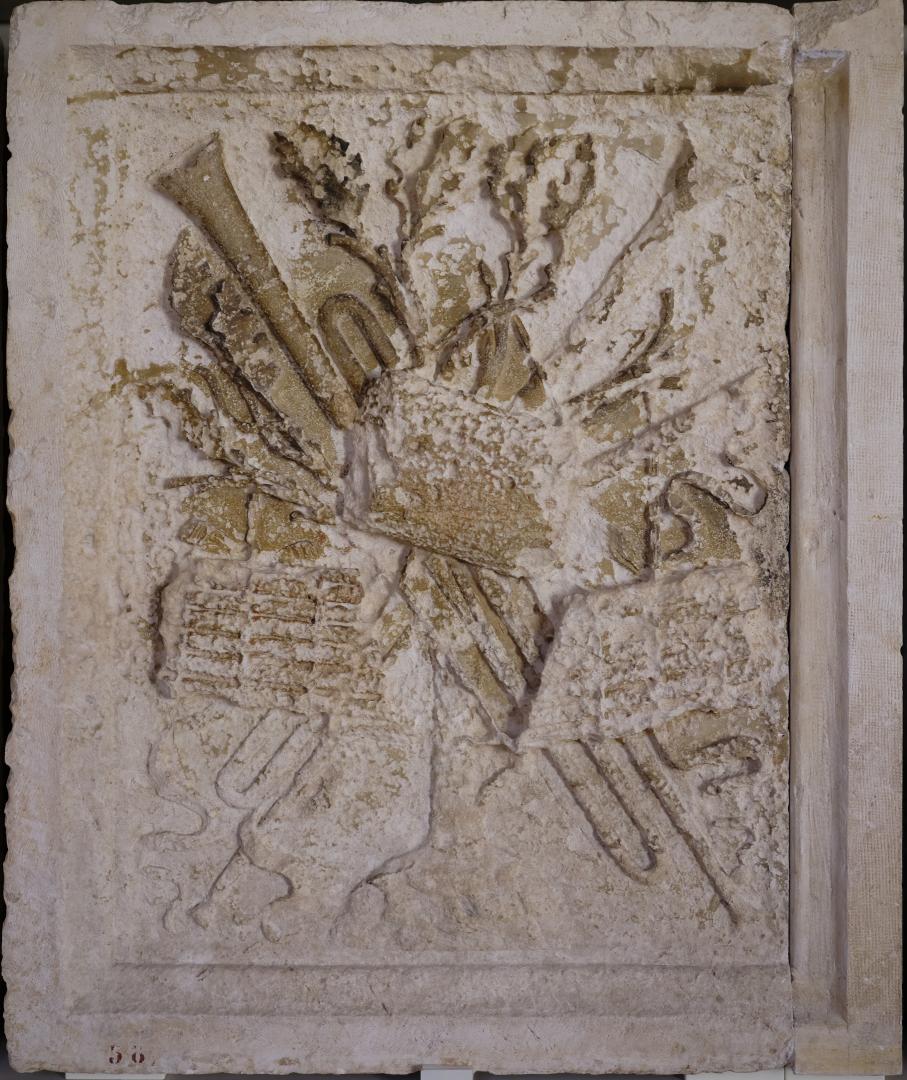

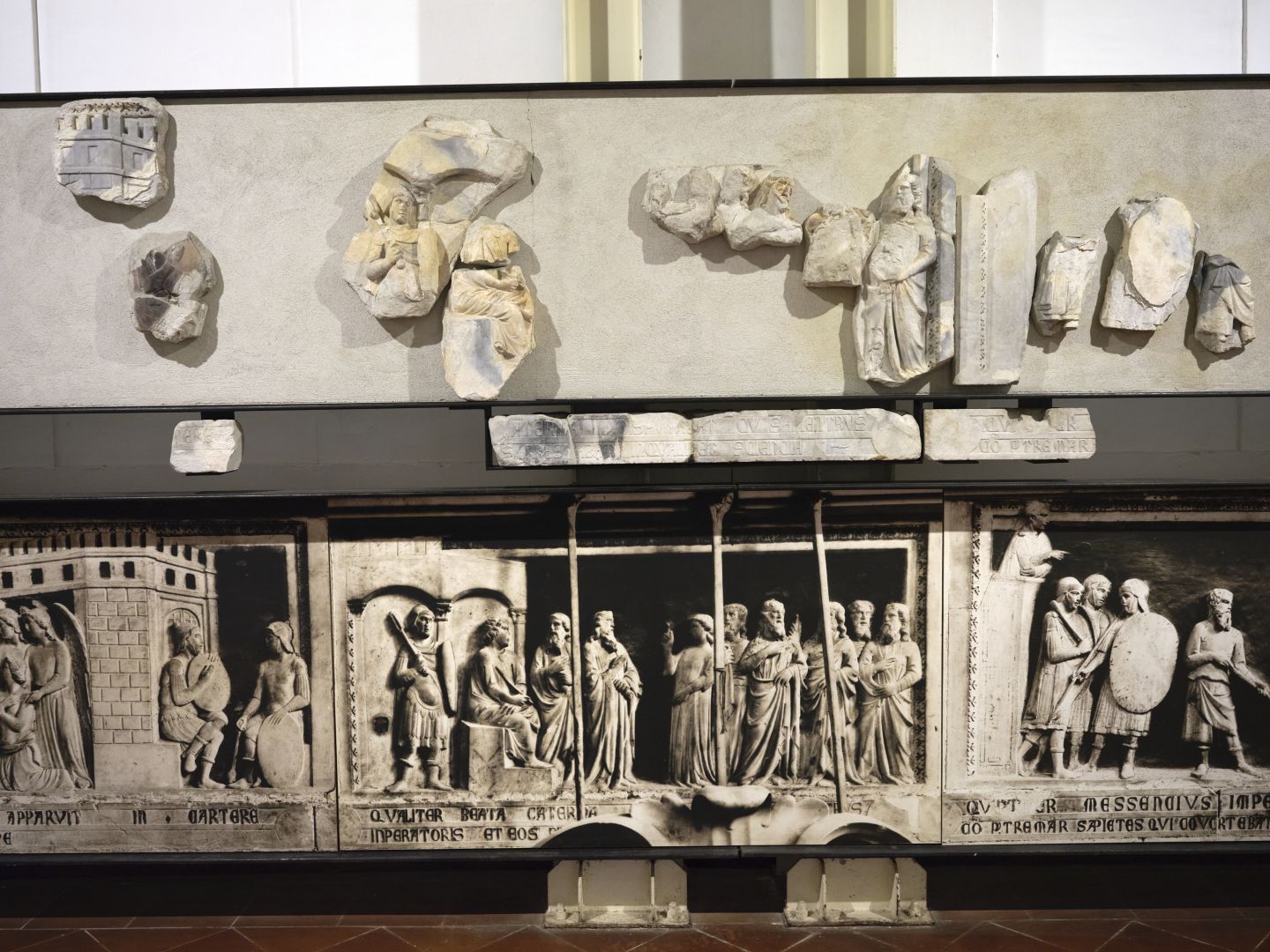

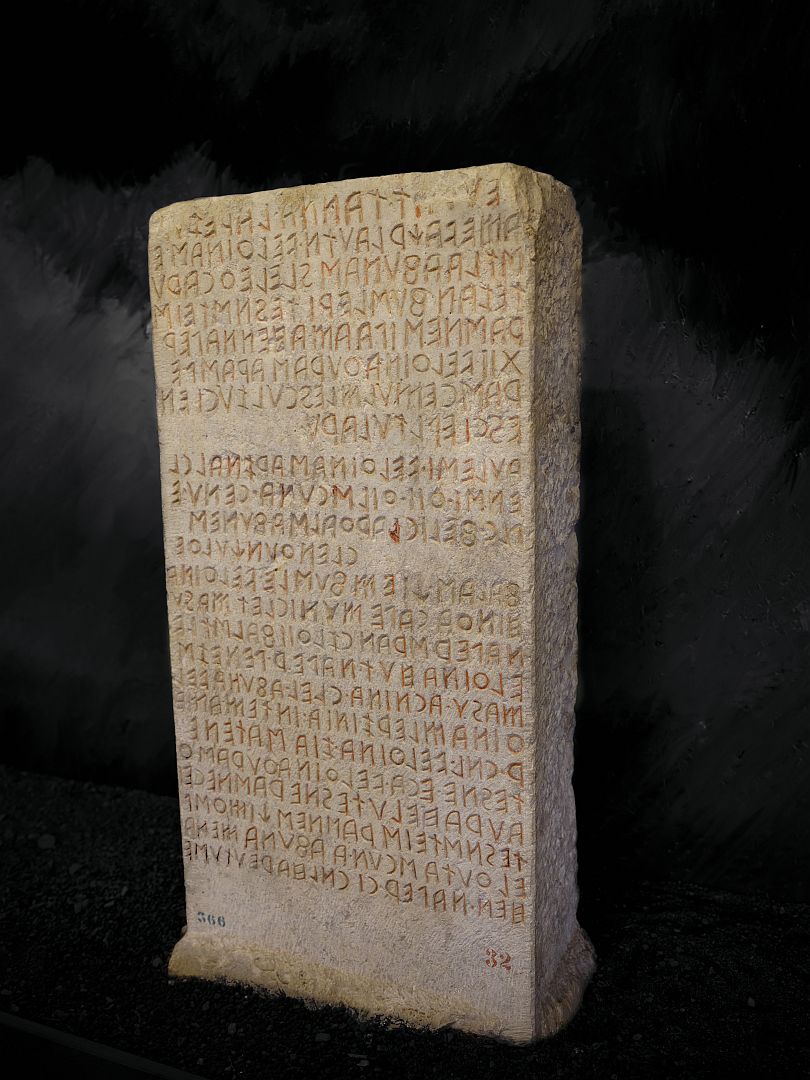

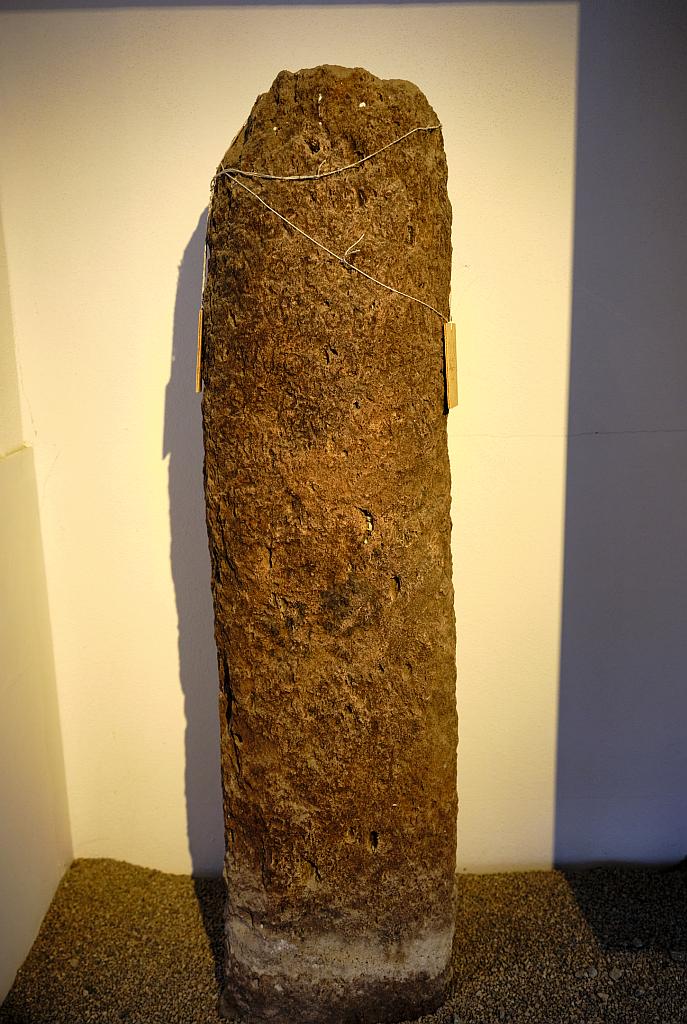

The Romans, unlike other Mediterranean powers at the time, invested in public infrastructure (in the words of Monty Python, “what did the Romans ever do for us?”). The photograph above is of a milestone on display in the Civic Museum in Torralba. The inscription is too hard to make out in the photograph, but someone has gone to the trouble of transcribing it, and according to the adjacent information panel, it was dedicated to the recently-deceased Emperor Aurelian in around 275 AD, and is 118,000 paces from… somewhere (the museum curators didn’t tell us).

A Roman Coastal Town

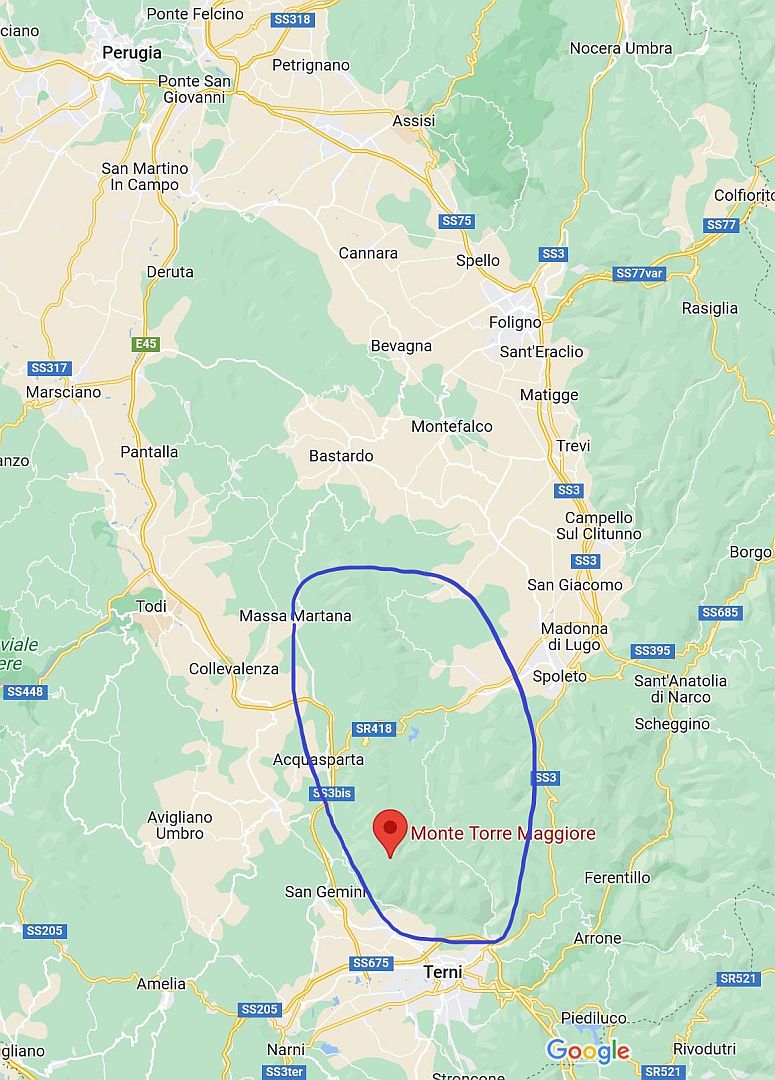

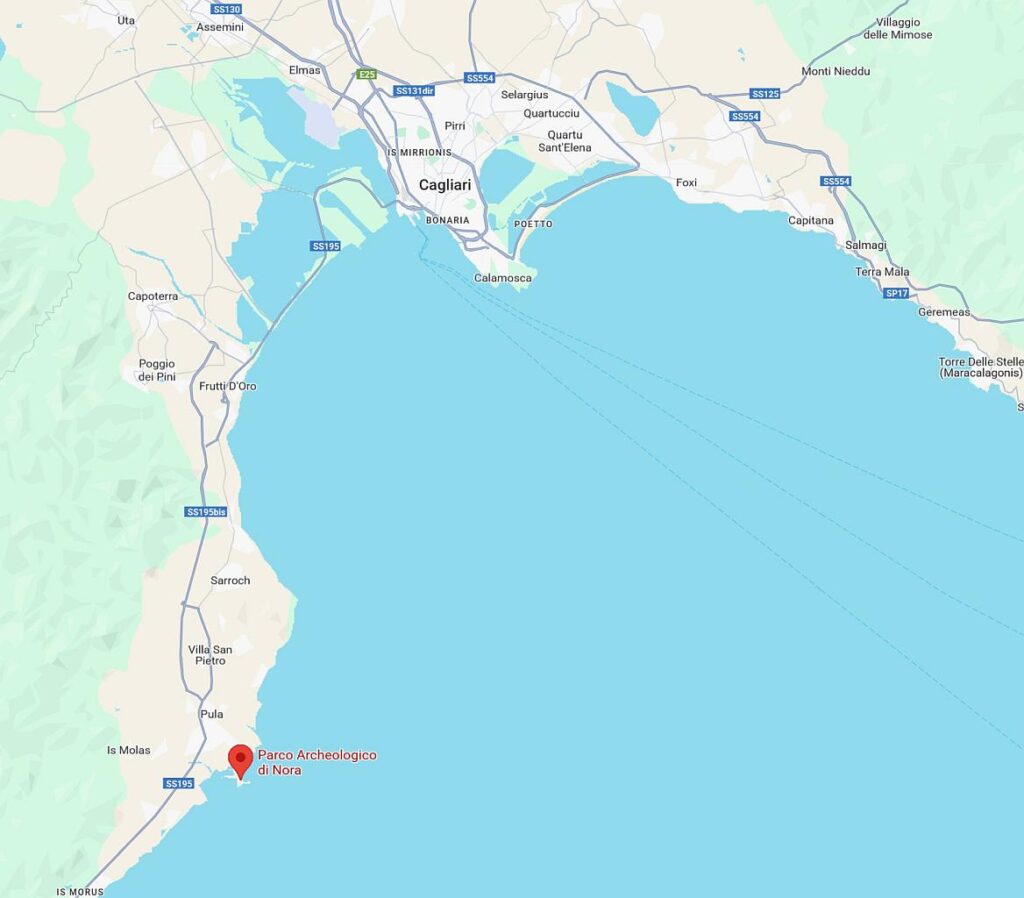

I mentioned in the post on Sant’Efisio that after the main parade around the streets of Cagliari, the saint’s effigy was then carried to the traditional site of his martyrdom, a town called Nora about 40km down the coast. On the way there, local communities turn out for mini-versions of the parade. Nora also has a highly-rated archaeological area, so we decided that on our way from Cagliari to our next stop on the west coast, we would first head south west to Nora.

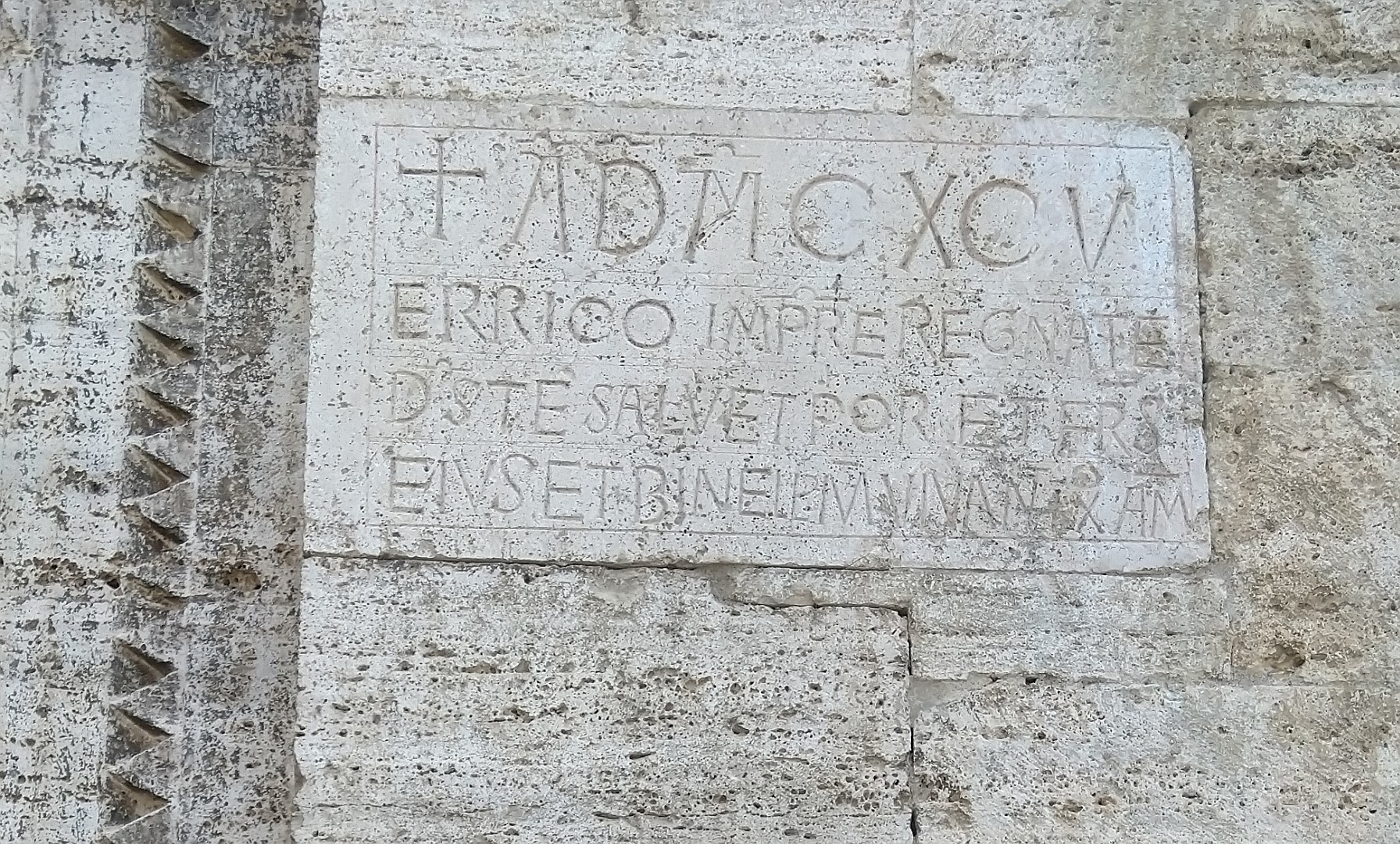

On the way we were occasionally held up on the road by decorated carts or people on horseback, on their way to honour the saint. Passing by the modern town of Nora, we arrived at the archaeological area, which is close to where the little Romanesque church, dating from 1089, marks Sant’Efisio’s martyrdom site.

On the approaches to the church, people were setting up for a traditional Italian religious festival, which is to say they were setting up trailers from which would be sold sweets, nuts, children’s toys and in Sardinia, great quantities of nougat.

The history of the site starts with the fact that it is next to a little headland that would no doubt protect trading vessels that anchored there. This anchorage led to the establishment of a Phoenician trading post, then a settlement. These days the headland is occupied by a watchtower of Spanish origin.

A stone found in the 18th Century, bearing an inscription in the Phoenician language and now in the Archaeological Museum in Cagliari, records the Phoenician presence there and, according to one interpretation, shows that the island was called Sardinia as long ago as the 9th or 8th Century BC. Adding to the story is where this precious stone was was when it was identified – ignorant of its meaning, medieval builders had found it lying about at Nora and used it as building material for the apse of the church of Sant’Efisio. Fortunately the inscription was facing outwards where it could be recognised, or it would still be there.

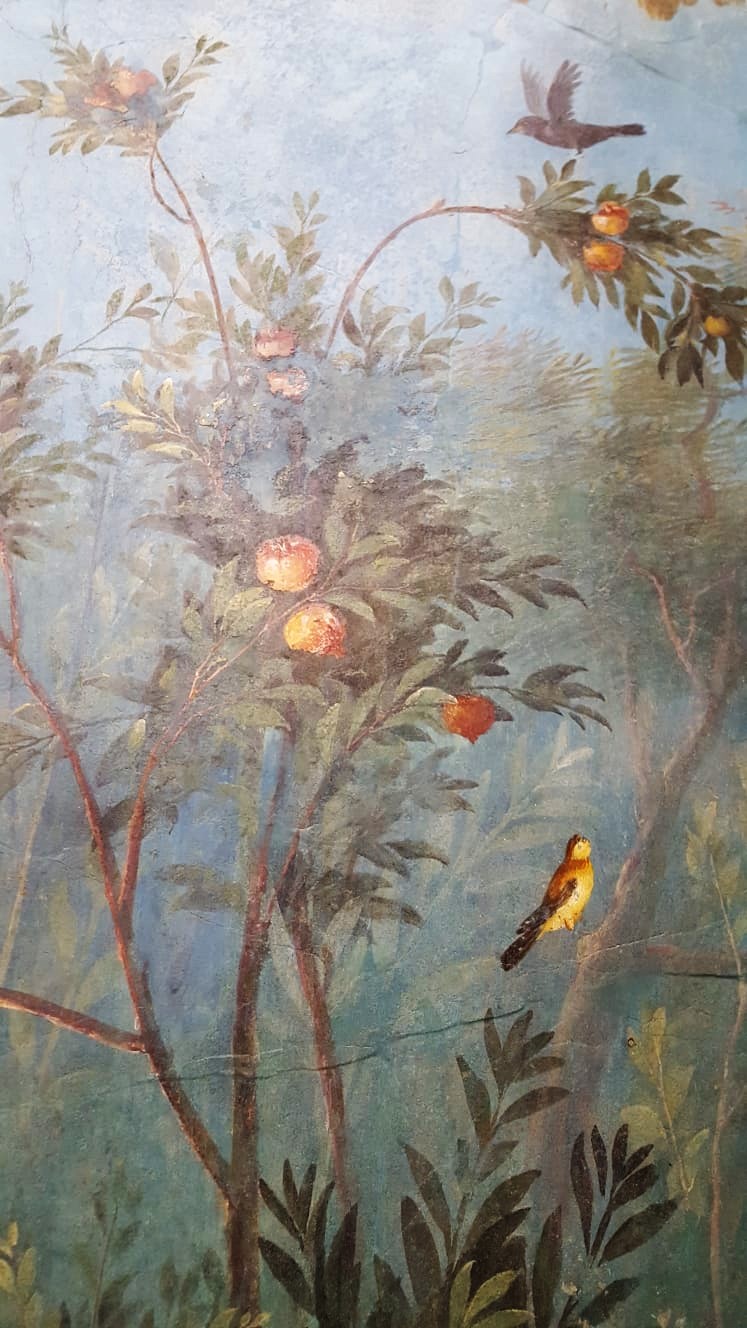

As the Phoenicians were supplanted as a trading nation by their colony Carthage, Nora became in due course a Carthaginian colony, then after the Punic Wars a Roman one. It is therefore a palimpsest of early Sardinian colonial history, although to the casual observer what you see is mostly Roman. Of the Phoenicians, a few burial sites were found in the 19th Century before the sea washed them away, and on a small rise there are the remains of a Carthaginian temple, although when I was there it was hard to distinguish any pattern in the stones under the profusion of spring wildflowers.

Looking at the remains of Nora, one is reminded that the “Pax Romana” was a real thing. While the Dark-Age people that followed Rome all had to live in fortified towns on hilltops for fear of attacks, the Romans, during their centuries of peace, generally got to choose, like us, places that were nice to live in, if they could afford it. And Nora is a lovely place beside the sea. It must have been very pleasant indeed to live there.

With some of the ancient town lying under land owned by the Italian Ministry of Defence and yet to be excavated, Nora doubtless has a few secrets still to be revealed.

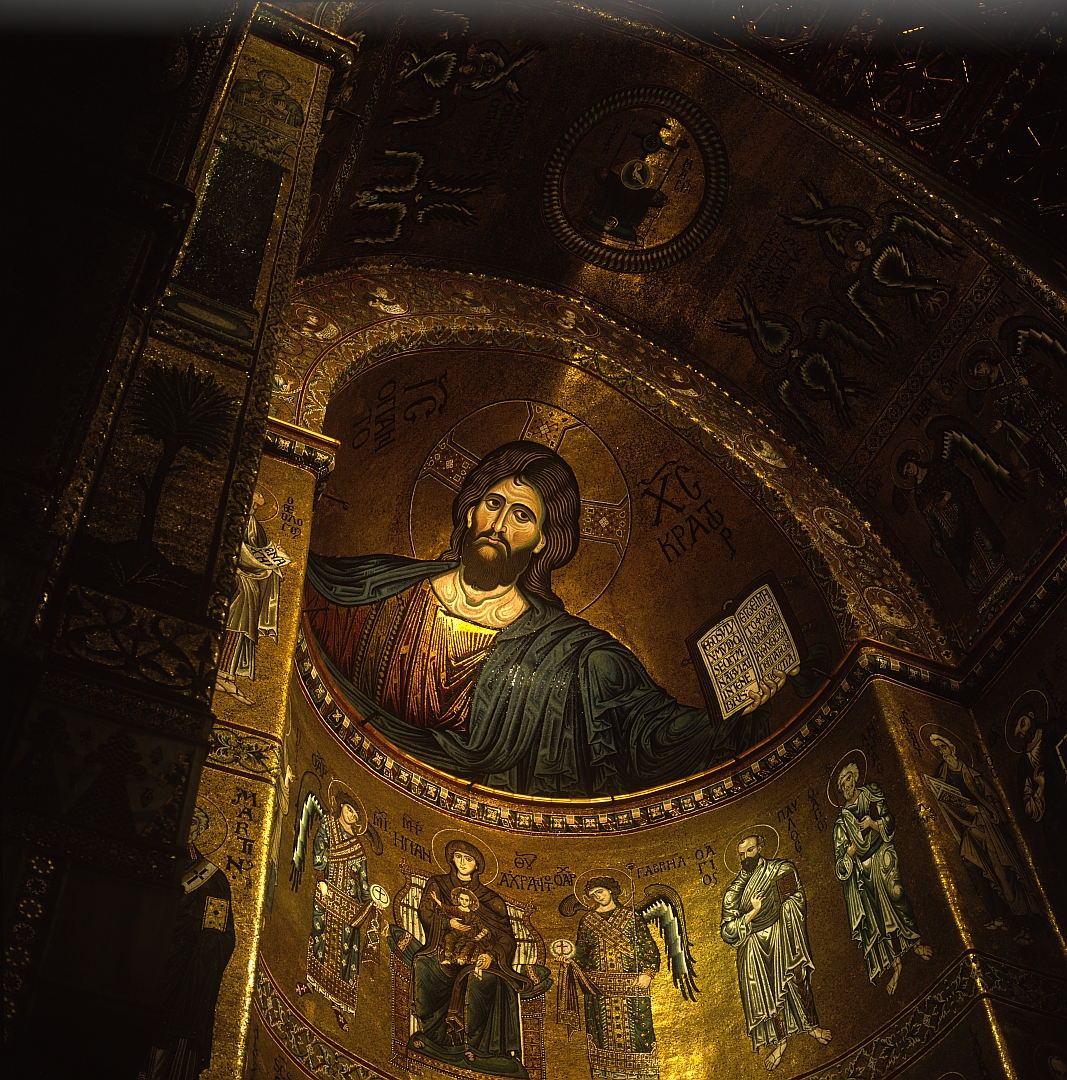

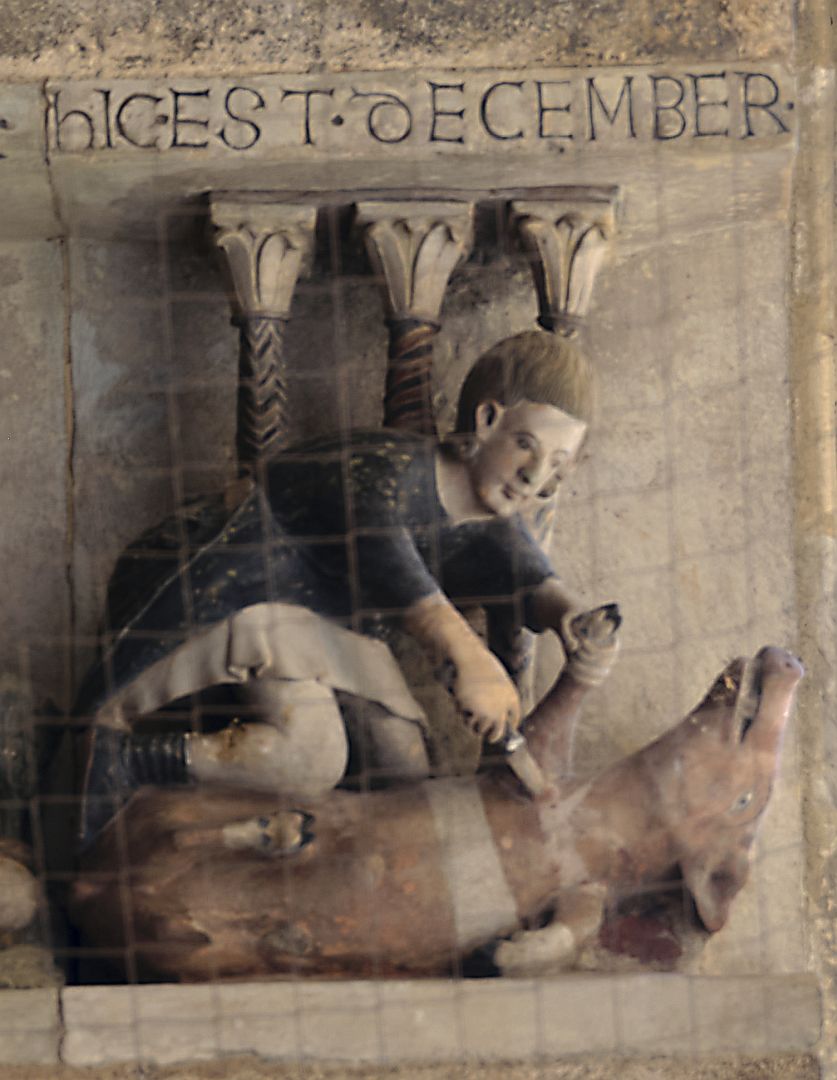

After Rome

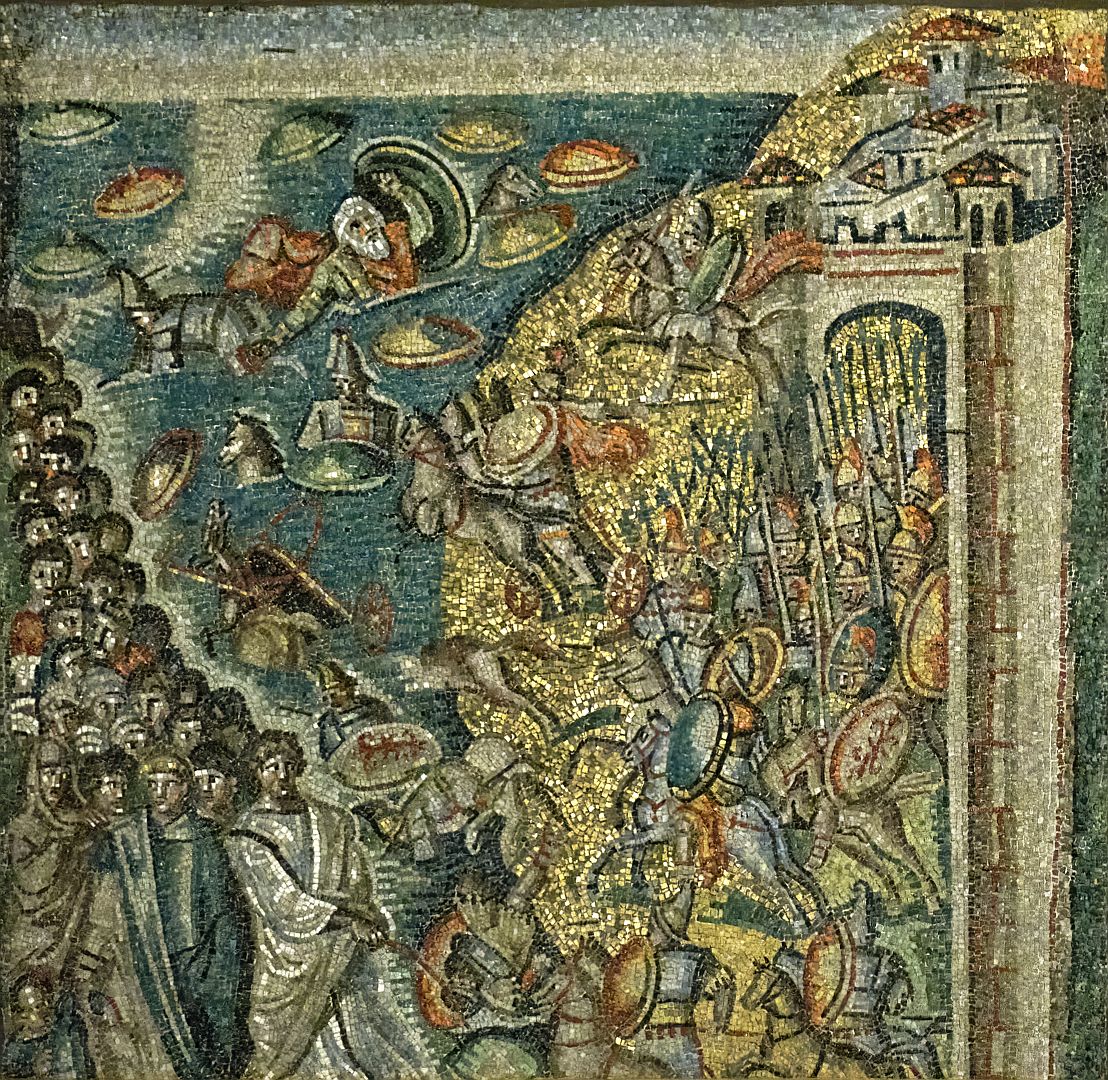

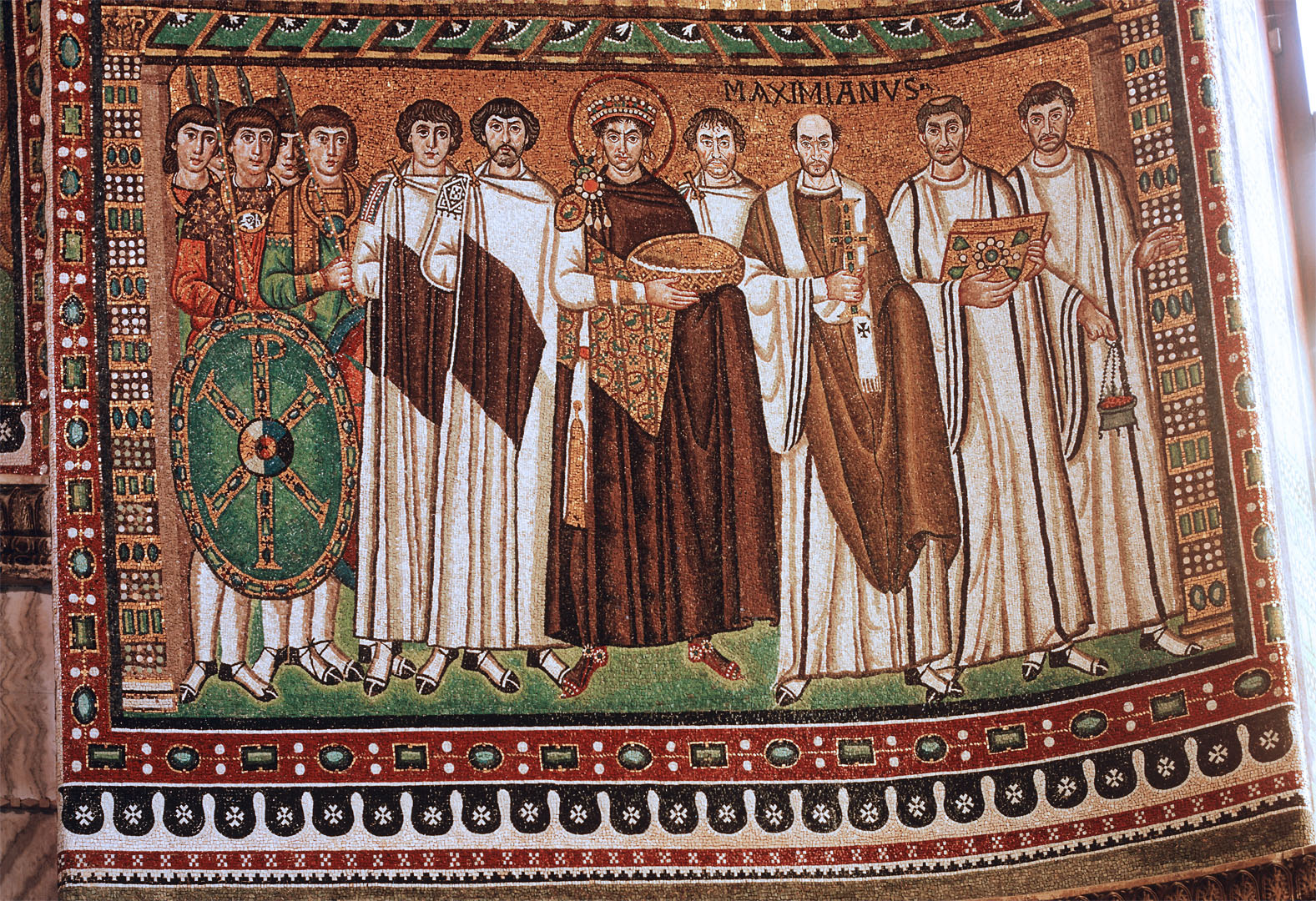

After the fall of the Western Empire Sardinia was invaded first by the Vandals (despite the name, presumably unrelated to the current graffiti problem in Cagliari) and then the Goths, but with the end of the Gothic War on the mainland, and the failure of the Lombards to invade, Sardinia remained part of Byzantine domains.

In time Byzantine power in the west became ever more attenuated, and unable to assist against the next threats, which were from Muslim Spain and North Africa. At that point Sardinia turned for help to the maritime republics of the mainland – Pisa and Genoa – and we may say that antiquity, as far as Sardinia was concerned, was over.

Postscript: Flamingos

The salt flats that surround Cagliari are famous for their flocks of flamingos. I was excited for the photographic possibilities and brought my longest lens along on the trip. However on the drive from Cagliari to Nora the flamingos were uncooperative, mostly with their heads underwater. Not only that but the vivid pink colour featured in my childhood book of birds was quite absent – they were practically white. The lens stayed in the bag.

Eventually in one of the toy stalls set up outside the church of Sant’Efisio in Nora I was able to photograph some, but not quite in the way I had anticipated.