In the Middle Ages and Renaissance there were some bad Popes, some worse Popes, and some truly despicable ones. Were there any good ones? There were some who were undoubtedly spiritually good men, but woefully incompetent rulers, like Celestine V whom we met in my post about visiting his hermitage in Abruzzo.

Quite a few were effective administrators and statesmen, but worldly, proud and vengeful, and curiously uninterested in spiritual matters. The best example of that sort is probably the irascible Julius II, who personally led the Papal forces into battle a couple of times. Others were interested in doctrine, but only to the extent of fiercely resisting intellectual freedom and scientific modernisation.

A “good” 15th-Century Pope was Nicholas V (1447-1455), who was the first to genuinely try to reconcile the Church with Renaissance humanism. Nicholas re-established the Vatican Library and commissioned important works of art from the likes of Fra Angelico – in the process taking the Domenican friar and artist away from his work in the Duomo of Orvieto.

But the Pope of whom I wish to write today is, to me, an even more fascinating character. A scholar, a writer, a diplomat and at one point a secret agent, the young Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini was not perhaps an obvious future Pope (John Julius Norwich describes his poetry as “mildly pornographic”). He did not even take holy orders until he was in his 40s. Nonetheless he became Pope in 1458 and took the name Pius II.

As Pope, Pius took an unusual approach to establishing his legacy. While not averse to promoting his own family, he avoided outrageous nepotism and self-enrichment. Instead he left two more enduring monuments – one physical and one literary. And a third was created in his memory by his nephew (another Pope, Pius III).

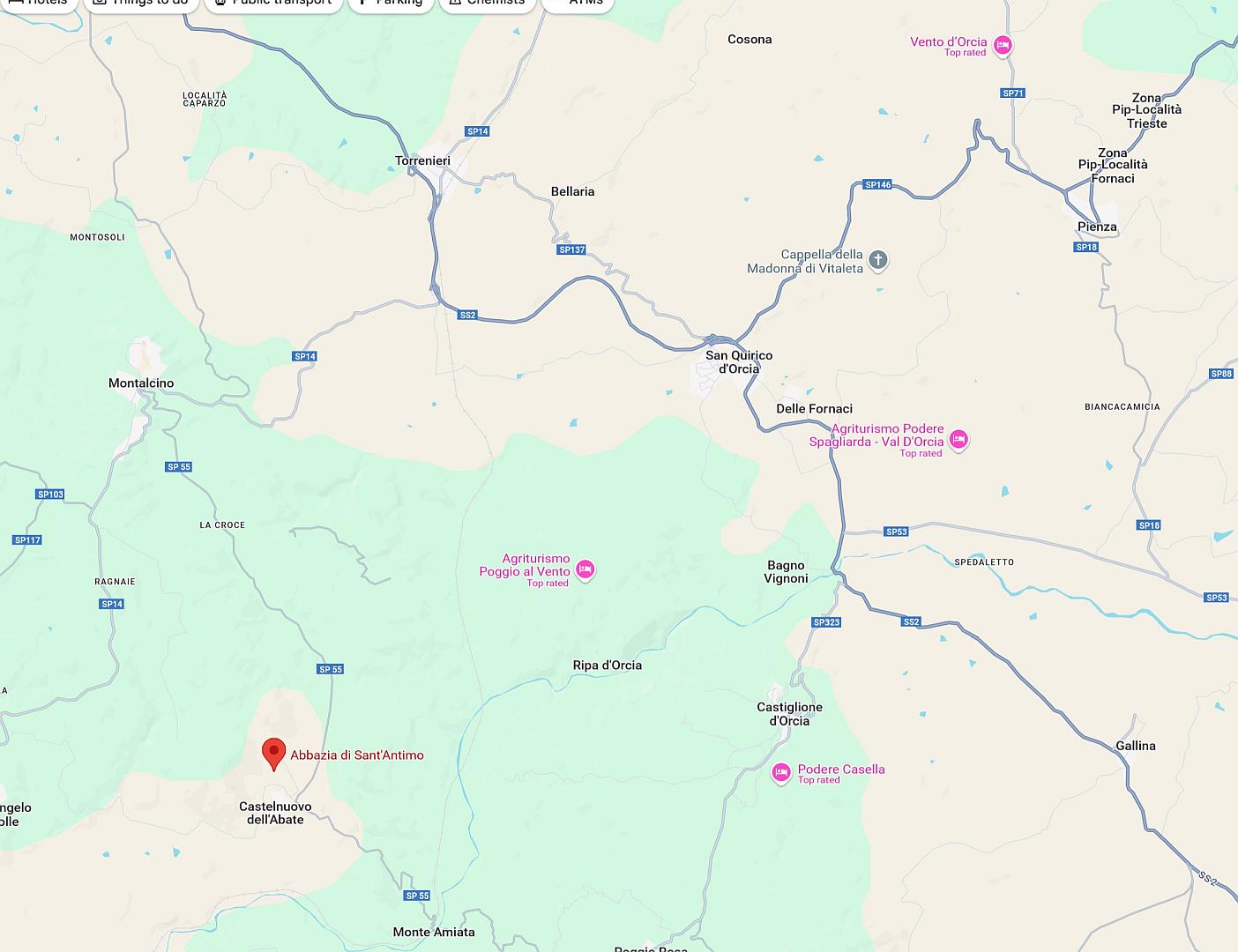

The physical monument is his home town of Corsignano, which he had rebuilt in the latest Renaissance style by the architect Bernardo Rosselino, and then renamed it Pienza after himself. Visitors to Pienza cannot fail to be struck by its beauty, but as they marvel at the views or sample the wine, cheese and salume, not all of them realise that its beauty is no accident; it was designed like that.

We have visited Pienza many times over the last 25 years. Although it is a bit more crowded these days than on our first visit in 1999, it always feels special. Among its attractions are the magnificent views from the town walls over the Val d’Orcia – I have published a few on this site, including in the post called A Storm in the Val d’Orcia and A Return to the Val d’Orcia. This article will give me an opportunity to post a few pictures of the town itself, taken during several visits over many years, while telling the story of Aeneas.

And the literary legacy? Like many a Renaissance humanist, Aeneas did a bit of writing on the side – rather a lot actually – and he was named Poet Laureate at the Imperial court. In addition to the erotic poetry, he produced plays, a novel (also erotic) and some histories. But the legacy I am referring to is an autobiography called the Commentaries, written in the third person during the last years of his life, and published posthumously and pseudonymously. It brings to mind Winston Churchill’s observation that “history will be kind to me, because I intend to write it myself”.

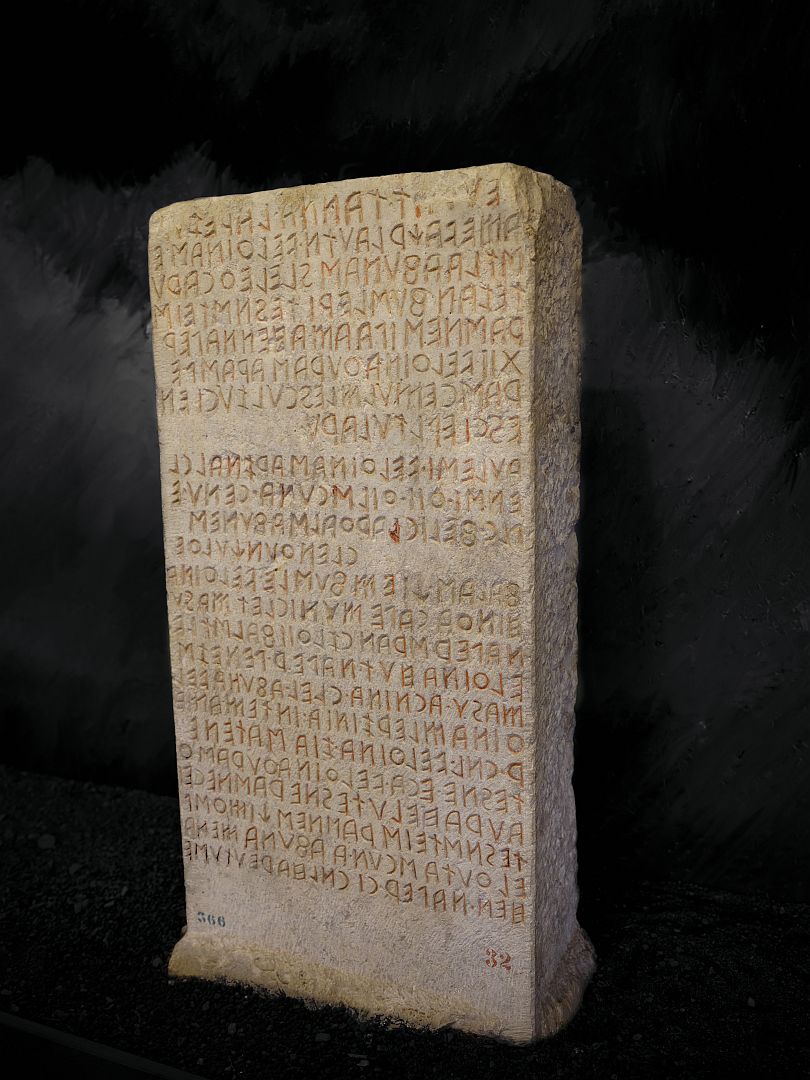

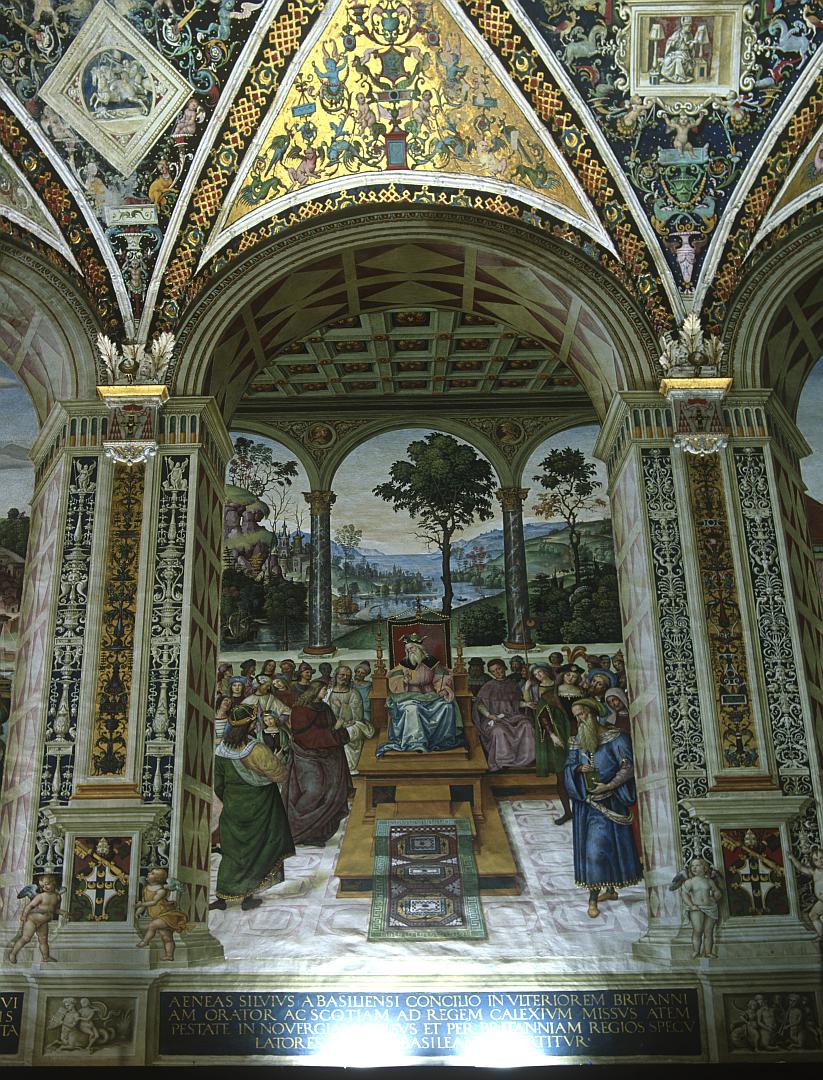

The third element of the legacy is to be found in the “Piccolomini Library” in Siena cathedral, established in Aeneas/Pius’s memory by his nephew, the future Pope Pius III. This library is decorated with ten frescoes by the master artist Pinturicchio, depicting episodes in Aeneas/Pius’s life, in some cases presumably drawn from the Commentaries. We met Pinturicchio in my post titled “Tough Guys in Art – The Baglioni of Perugia“.

Note: my photographs of the Piccolomini Library were taken with a film camera on a visit to Siena almost twenty years ago. Because I was using slow outdoor film and tripods were not permitted, I needed to steady the camera on bits of furniture which meant they were all taken from rather low down, and from further away than I would wish. I hope to revisit Siena soon and will attempt to take better ones – if so I will update this article.

The Name’s Piccolomini, Aeneas Piccolomini

So what about the secret agenting? I’m glad you asked, but let us start at the beginning. Aeneas was born in Corsignano (later Pienza) to an ancient but somewhat impoverished Sienese family. It seems that the young Aeneas actually helped his father with farm work, which is not necessarily evidence of absolute poverty – in this era genteel families often owned farms, and tending vines and olive trees was considered an appropriate way for people to cultivate not just the land but philosophical thoughts. Whatever it tells us about Aeneas’s childhood, it is however an excuse to show some pictures of agricultural land just outside Pienza.

At university in Siena and then Florence, Aeneas studied humanities, including history, and civil law. He returned from Florence to Siena intending to teach, but soon took a post as secretary to a cardinal on his way to the Council of Basel. These 15th-Century councils had their origins in the earlier period of schism after the Avignon Papacy, as bishops, archbishops and cardinals tried collectively to exercise authority over the Popes. And when you had two or even three rival Popes all claiming to be the ultimate authority in the Church, appointment of a general council of senior churchmen was an obvious method to try and resolve those competing claims. It was a short step from that to the councils deciding that they were in fact superior to the Pope of the day in the church hierarchy.

The notion that the Church should be governed by councils rather than Popes – known as conciliarism – gained a good deal of support in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. The Popes did everything they could to frustrate the councils – sometimes ordering that they be dissolved, which the councils tended to ignore. Sometimes a council would even declare the Pope deposed and elect their own (known now as antipopes).

So Aeneas went to Basel, and a few years later in 1435 he found himself working for one Cardinal Albergati. Albergati, it seems, had a special job for the young man. In my post on Catherine of Siena, Cardinal Albornoz and Sir John Hawkwood, I mentioned in passing that the Church was desperate to bring an end to the Hundred Years’ War between England and France. Decades later this was still the case, and Albergati’s cunning plan was to send a secret mission to King James I of Scotland to persuade the Scots to launch a surprise attack on England, thus diverting English military resources away from France.

Aeneas set sail for London, intending to travel overland from there to Edinburgh, but the English, suspicious, refused him permission to land and he had to return to the Netherlands, whence he took a ship directly to Scotland. Or at least it would have been direct had a fierce storm not blown them almost all the way to Norway. Fearing for his life, Aeneas vowed that if he made it to Scotland he would walk barefoot to the nearest shrine to the Virgin Mary. This he did, over several miles in very cold weather which gave him arthritis for the rest of his life.

Just how successful Aeneas was is hard to say – the Commentaries are apparently a bit vague on the outcome of the mission. History tells us there were a few border skirmishes in the 1460s between Scotland and England which do not seem to have had a particularly decisive influence on the Anglo-French war and would probably have happened anyway.

After Scotland Aeneas made his way home; this time he was able to make it across the border and travelled down through England disguised as a merchant (doubtless he was not keen on another sea voyage). The Commentaries contain some fascinating observations of life in 15th-Century Britain: for example, there is nothing the Scots enjoy more than hearing abuse of the English, while across the border the English men and children withdrew to the safety of fortified towers each night for protection from raiders, leaving the women downstairs (apparently Scots raiders would not kill the women). They also left Aeneas downstairs as well, which worried him greatly, even though the women were beautiful and, he wrote, sexually available. He claims to have declined their offers though, and spent the night hiding in a stable hoping to avoid a visit from Scottish raiders. Fortunately none appeared, although he was unable to sleep because of the nanny-goats that were stealthily pulling the straw out from his mattress.

Germany and the Empire

On his return to Basel he found himself working as secretary to the last Antipope of the Great Schism, Felix V, previously Amadeus VIII, Duke of Savoy. Felix sent Aeneas on another mission – not a covert one this time – as an emissary to the Diet of Frankfurt and the Court of the German King (or Holy Roman Emperor) Frederick III. Frederick recognised his literary talent and it was he who made Aeneas Poet Laureate, which Aeneas repaid by writing a biography of Frederick.

Aeneas resigned his job with Felix and followed Frederick to Vienna where he spent the next few years of his life under the patronage of the Imperial Chancellor, writing works of literature, history and theological and political tracts. This was the most productive period of his life in various ways, since as well as his literary output he fathered several illegitimate children.

Aeneas was sent to Rome in 1445 where, it seems that despite having spent all his working life with the conciliarist faction, he changed sides and returned to Vienna on a mission to reconcile the German princes with the Papacy. In this he was very successful, and on the death of the current Pope (Eugene IV), Felix the Antipope voluntarily resigned his office and was not replaced. The “Great Schism” was at an end.

Holy Orders

It was now that Aeneas finally took holy orders, having refused ordination previously on the grounds that he did not want to give up sex (something which did not appear to have been an insuperable obstacle for many other senior churchmen of the day). His promotion was rapid – a bishop in a year, a cardinal within a decade, and Pope two years after that in 1458.

Pius II (as we shall now call him) was one of the most talented men ever to become Pope, but he was not destined to be a great one. It wasn’t all his fault – circumstances were against him. Constantinople had fallen to the Turks in 1453, to the general horror of Christendom, and Pius thought that his diplomatic skills would be enough to pull together a coalition of European states to mount a crusade to retake the city. It was not to be. Pius invited all the rulers to a conference at Mantua, but most either declined or gave ambiguous replies, and when Pius turned up at Mantua there were almost no other delegates. It was a humiliating illustration of the loss of Papal authority, and Pius concluded that it was the fault of the conciliarist movement of which he had been such a partisan and advocate. He issued a bull declaring any appeals to a general council of the Church to be heretical – in which, obviously aware of the awkward contrast with his previous position, he said “reject Aeneas and accept Pius”.

He didn’t give up. Buoyed by the news that Hungary and Venice were minded to join the crusade, he arranged that all the forces should meet at Ancona on the Adriatic Coast before proceeding. But after an arduous journey he reached Ancona to find virtually no-one there. A few days later the Venetians did arrive, but the fleet was far smaller than expected. It was too late anyway; Pius was dying. When the news came of his death a couple of days later, the “crusaders” quickly turned around and went home. It was over.

Pienza

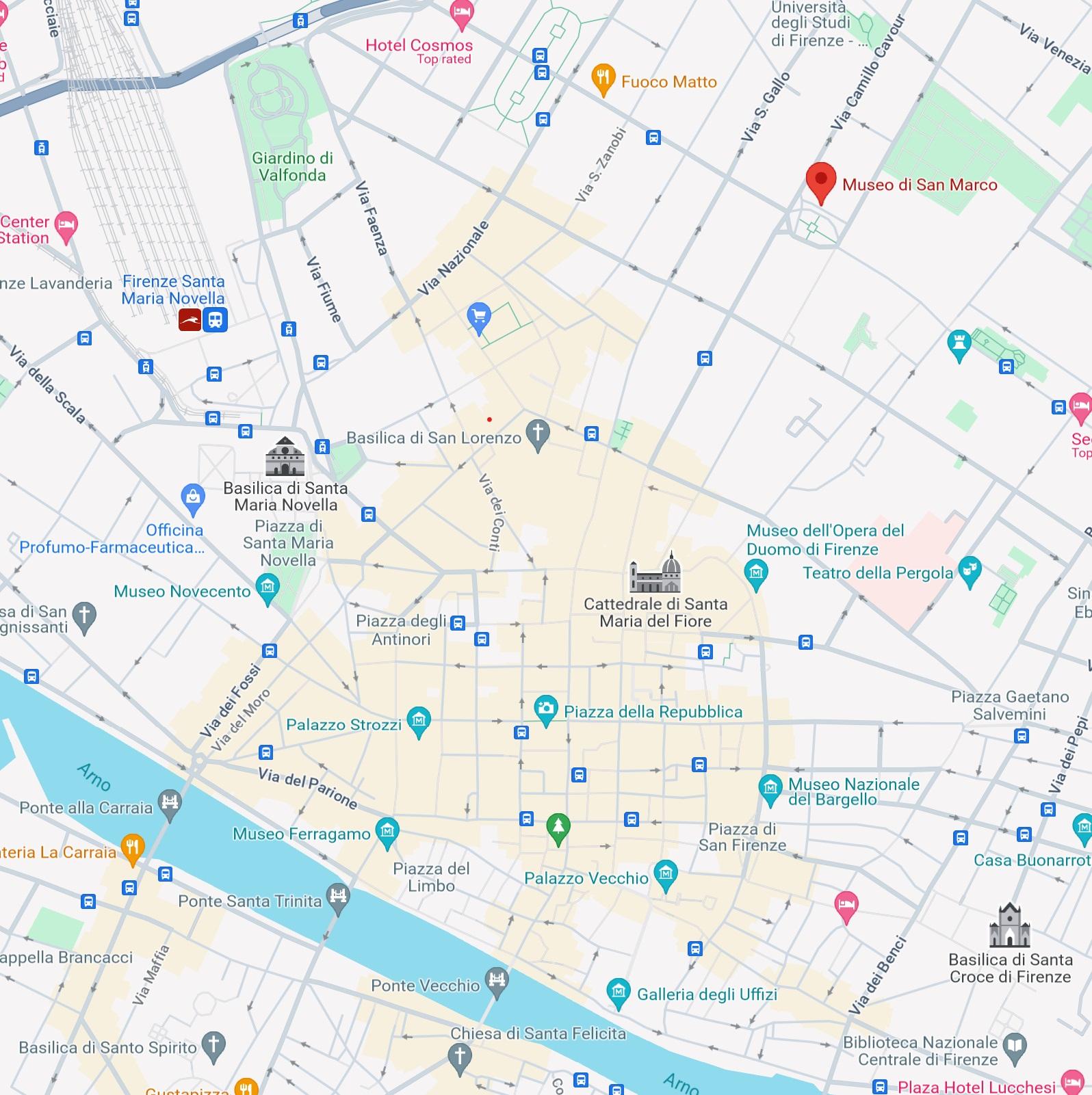

Let us not end the story with that disappointment though, but return to Pius’s gift to his birthplace, his family and to us in posterity: the beautiful town of Pienza. I have been unable to find a detailed description of what if anything remains from the medieval village of Corsignano, but looking at the map I see no winding medieval lanes. A broad street (now named Corso Il Rosselino after the architect) connects the two main town gates, and all the other streets more or less follow a grid pattern. That looks like deliberate design, and since I don’t believe Corsignano had ancient Roman origins, it is plausible that the previous streetscape was obliterated.

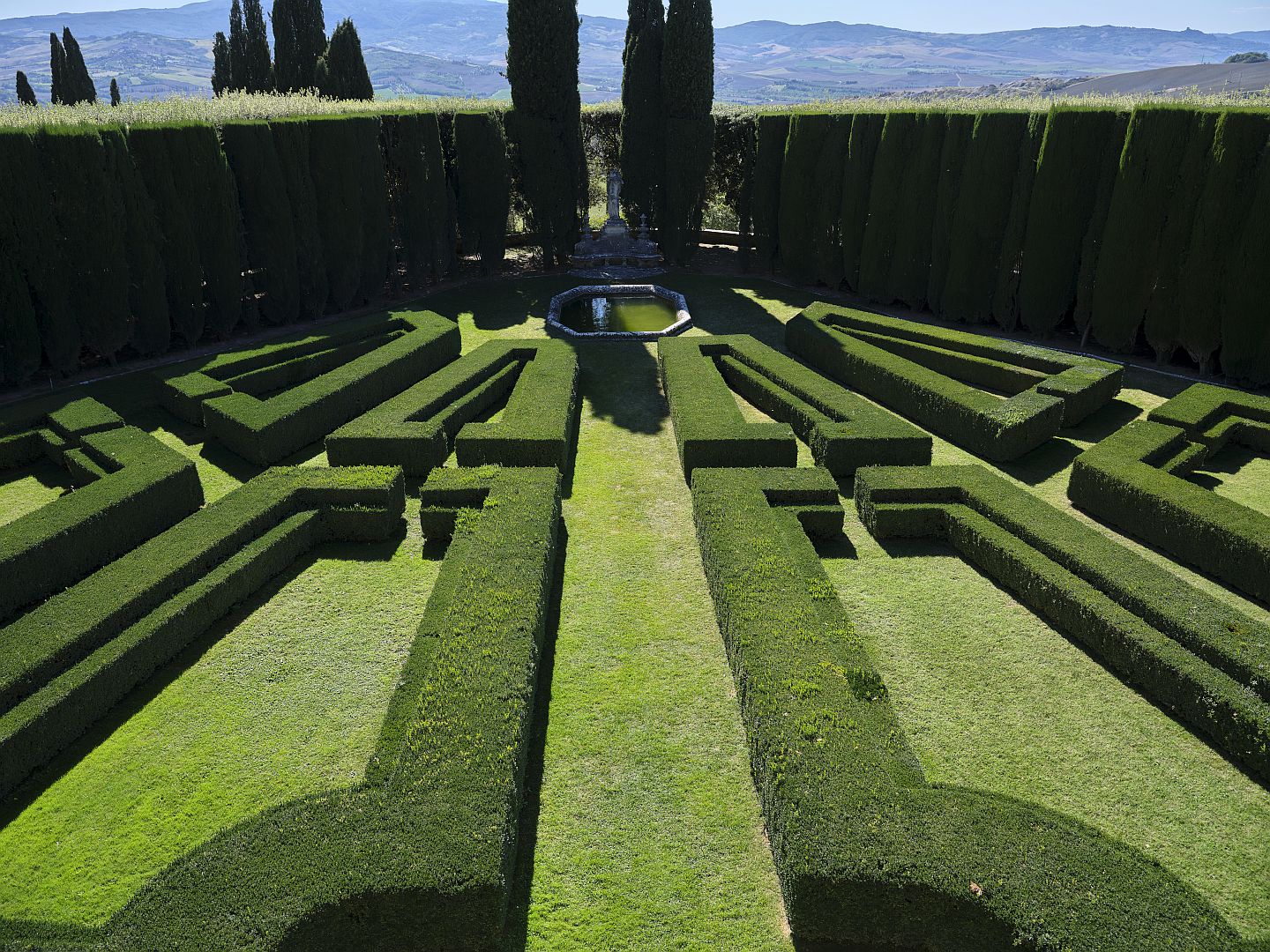

What is beyond doubt is that the focus of the new town is a central Piazza (Piazza Pio II, the Italian for Pius II), bounded three sides by the town hall, the Duomo or cathedral, and the Palazzo Piccolomini, built for Pius’s family and now an expensive hotel.

The Duomo has been the source of some concern over the years as the apse end of the building was built out over a steep slope and there has been some subsidence. If you enter the building you can see that the floor is lower at the far end. Reinforcement work has been undertaken, and you can have a look around inside without worrying about ending up down in the valley below.

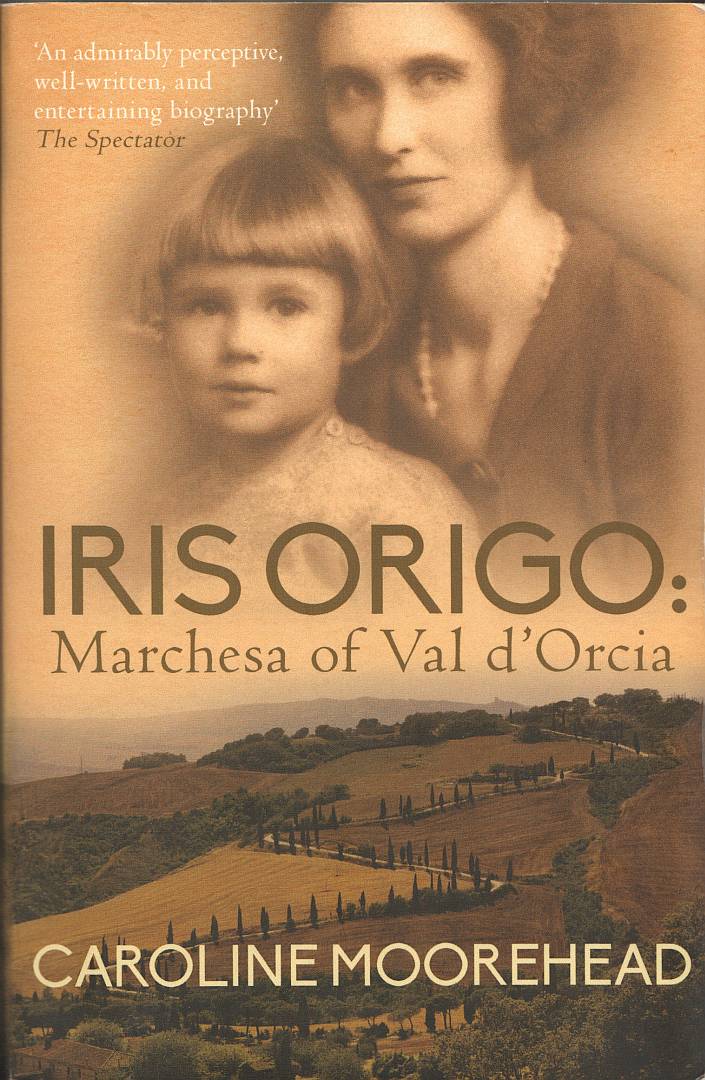

There are more recent marks of history. As I described in my post on Iris Origo, in 1944 the Val d’Orcia was the scene of some fierce fighting between the advancing British and the retreating Germans. Pienza was in a strategic location to control northward movement. If you look at the gate at the eastern end of town, the Porta al Murello, you will see above the arch a plaque saying “destroyed 15 June 1944, reconstructed October 1955”. The reconstruction is stylistically consistent with the rest of the town (thank goodness) so hopefully it is an accurate replica.

And on the outside of the Duomo (at the end that threatened to slide down the hill) you can see damage from bullets and shrapnel, left deliberately unrepaired as a witness to those difficult times. We must be grateful that the damage was not greater.

Sources

Pienza is a major tourist destination, so there are many sites online which describe its history and rebuilding, with varying degrees of historical accuracy. One site of which I had high hopes is one supposedly maintained by the Italian Government on UNESCO sites, but it has been down whenever I tried to reach it. You may have better luck, in which case it is here.

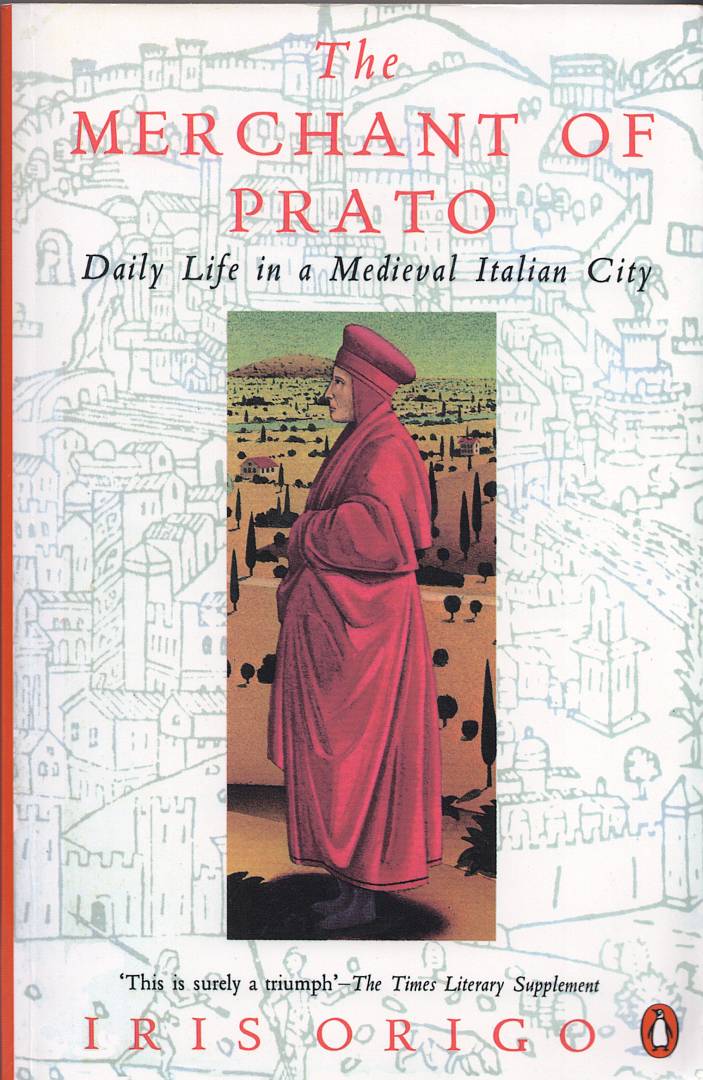

And Aeneas/Pius was an important historical figure, so he is mentioned in many histories, both in books and online. As always The Popes, A History by John Julius Norwich (2011) is both informative and entertaining.