Welcome to another article on paleochristian churches – buildings that survive from the early Christian era. In this case, the church is the Basilica of Santa Sabina all’Aventino, in Rome.

As I said in the introduction to this series,”paleochristian” is a somewhat elastic term; in some contexts it is used quite strictly to refer only to the very earliest periods, while in others it might apply more broadly to periods in the first millennium AD when Christian art, architecture and doctrine were all still evolving. I’m not a proper historian so I lean towards elasticity, selecting my examples on the basis of what they can show us that is different to the familiar architectural and artistic conventions of the Middle Ages and onwards, and also because really old things are very cool.

Since the Middle Ages the term “basilica” has meant a large church, granted special privileges by the Catholic Church. But in ancient Roman times, it referred simply to a large public building, used for various purposes including law courts, tax offices and so on; the colonnaded side aisles could be subdivided with curtains so a basilica might serve multiple purposes at the same time. If dog licences were a thing in ancient Rome, that is where you would have gone to buy one.

Basilicas were built to a standard plan, and after the establishment of Christianity as the state religion under Constantine, the basic plan – and the term – was adopted for large churches.

If you are a regular reader you will know that I am often disappointed to find that very old ecclesiastical art and architecture can be hard to find beneath later – often baroque, but also Renaissance – accretions. If you find yourself similarly disappointed, then I can recommend Santa Sabina, which is the oldest surviving basilica in Rome that retains its original appearance. While it did have some internal additions in the 16th Century, these were removed in the 20th.

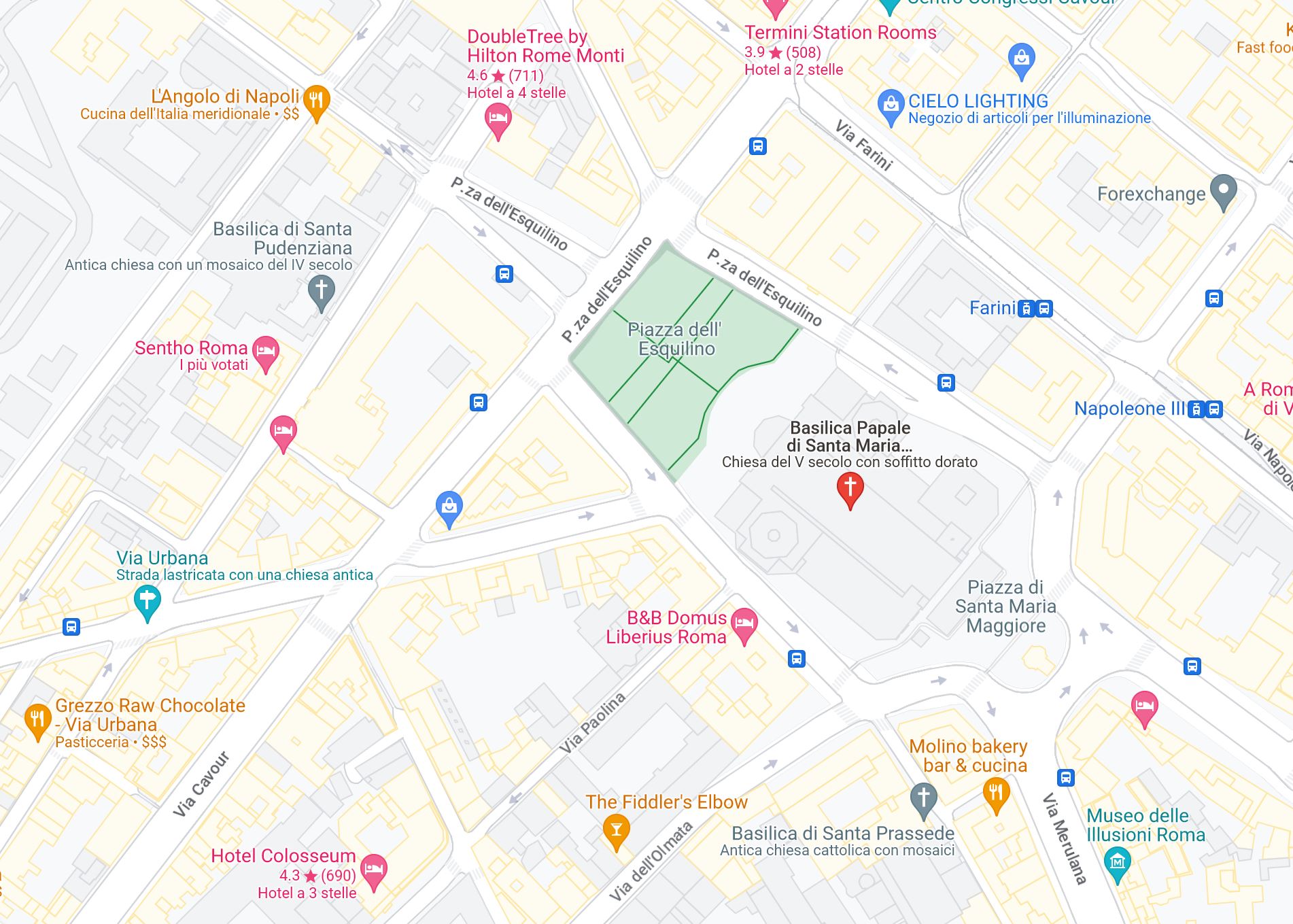

Dating from 422 or so, the Basilica of Santa Sabina is a couple of decades older than the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore – but it is in something much closer to its original condition than the mighty basilica of Santa Maria.

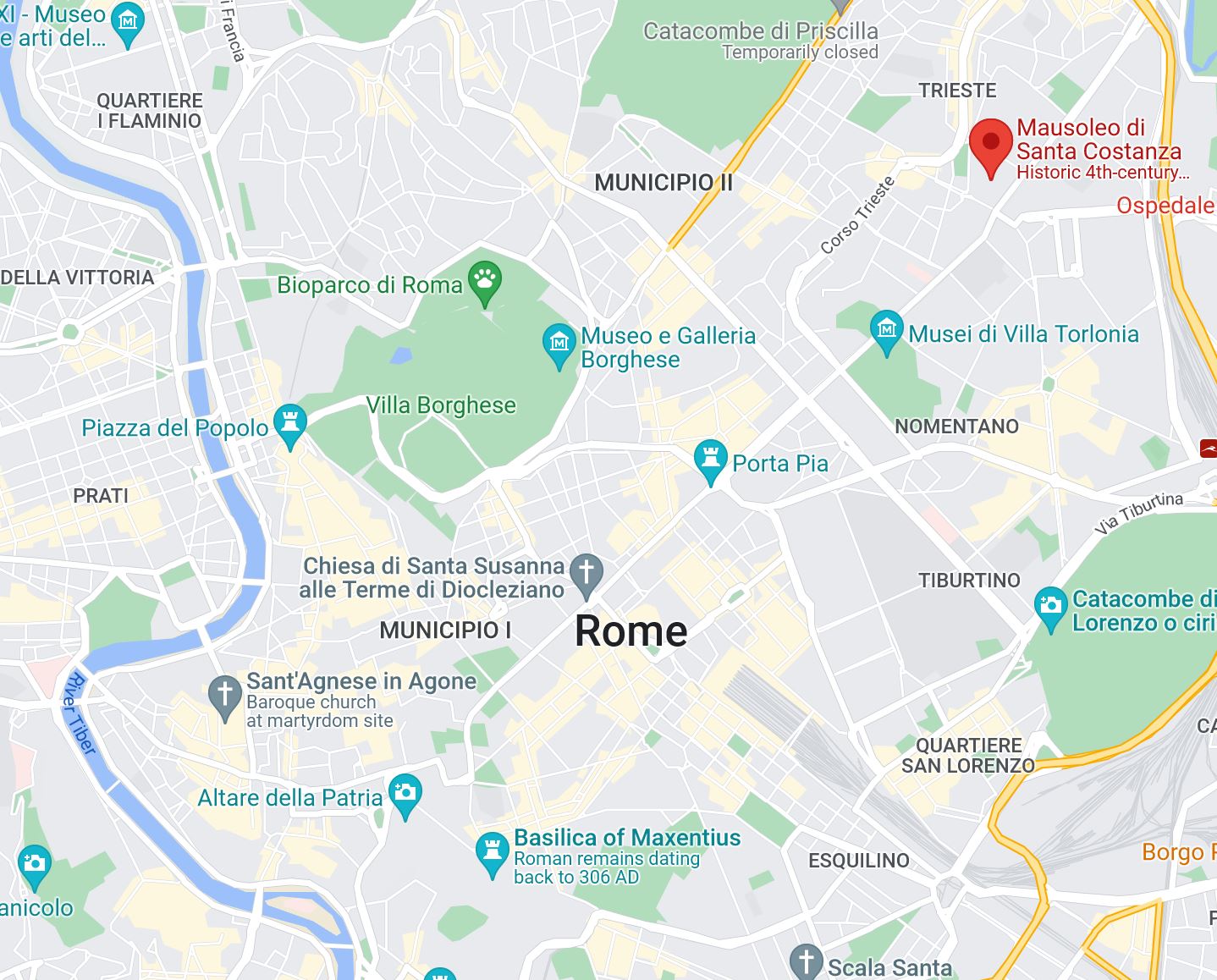

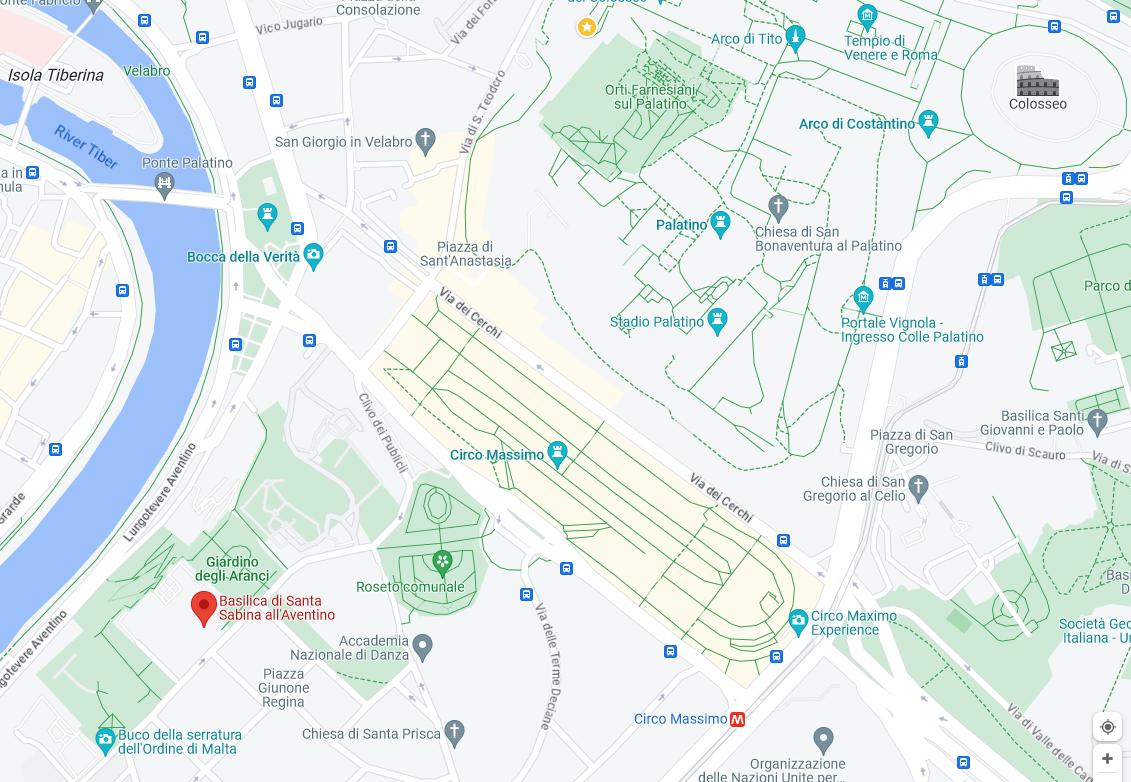

Santa Sabina is also easy to get to if you are in Rome. It stands on the Aventine Hill – that’s the southernmost of the ancient seven hills, beside the Tiber, next to the Circus Maximus and across the river from Trastevere. There’s a pleasant park there called the Giardino degli Aranci (Garden of the Oranges) from which you get one of the better views of Rome.

Unless you arrive there in a bus or a taxi, or on one of those blasted electric scooters, you will probably do what we have done each time and slog up the hill on foot from the Circus Maximus, or from the Lungotevere (the avenue beside the Tiber). If you take the former route you will see a pleasant rose garden on the way. It is on the site of a former Jewish cemetery, and the designers paid their respects by laying out the paths in the form of a menorah.

When you get to Santa Sabina, in the car park you might see an immaculate old Lancia or Alfa Romeo with white ribbons on the bonnet, because the church is a very popular place for weddings.

In ancient republican Rome the hill was the site of several temples dedicated to deities associated with the plebeian classes, but by imperial times the hill seems to have become a very up-market suburban area, with luxurious houses owned by aristocratic families, and a temple of Juno. One of the houses is said to have belonged to a lady called Sabina, a Christian convert who was martyred in the 2nd Century and later canonised. I don’t know whether Sabina’s house became a church after her death, but in any case there would probably have been no continuity with the later basilica dedicated to Sabina, because in the early 400s the area is thought to have been completely destroyed when Alaric the Goth sacked Rome. That makes sense – Alaric ordered his troops to respect religious places, but private houses in a wealthy suburb would have had no such protection.

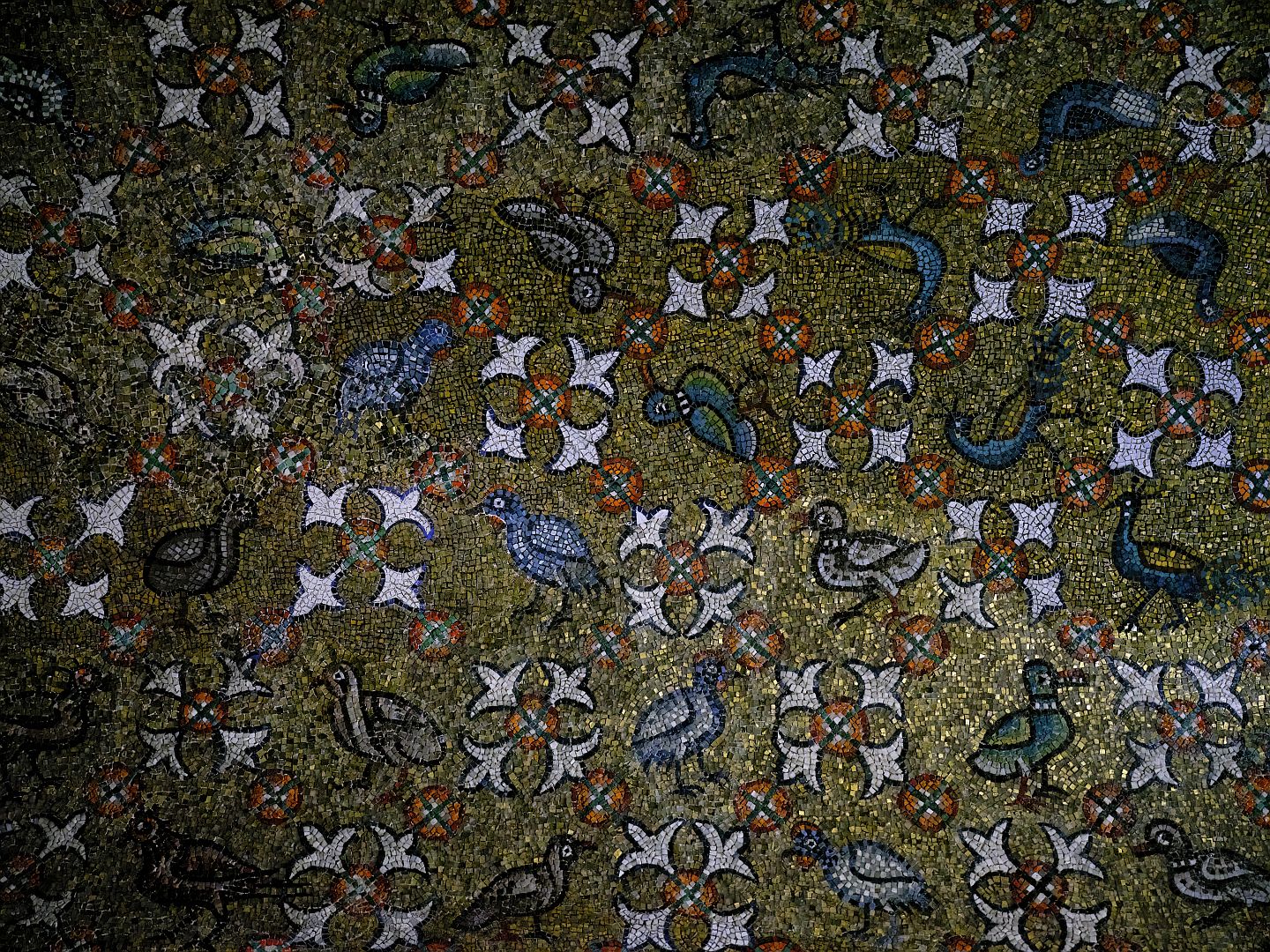

It must be said that even some Catholic sources are a bit dubious as to whether “Saint Sabina” even existed. One scholar argues that the real-life Sabina was likely to have been a wealthy 5th-Century donor of the land on which the basilica was to be built, and that the whole story about the 2nd-Century martyr was an early medieval invention. This is by no means impossible; in my post about Santa Costanza and Sant’Agnese we saw how two completely different Costanzas appear to have been postumously conflated into a single rather implausible saint. And it is not hard to imagine that “Sabina’s Church”, ie the church built on Sabina’s land, became “Saint Sabina’s Church” over time, creating the need for a confected hagiography to explain who the purported saint had been.

As we saw in my post on A Return to Ravenna, when the Gothic army left Rome, one of their hostages was the young Galla Placidia, daughter of the Emperor Theodosius, who was later to marry one of her captors and later still became, as regent for her son, the last competent ruler of the Western Empire. As a wealthy Roman lady, might our possible real Sabina have moved in the same circles as Galla Placidia, and perhaps met her? It is an interesting but unprovable speculation.

What is known for certain is that in the 420s, not long after the sack of Rome by the Goths, a churchman called Peter of Illyria commissioned the basilica that when complete twelve years later would become known as Santa Sabina. I wondered what this area might have looked like then. Only a few years after the sack, Rome was already experiencing severe depopulation, and the wealthy people who had lived on the Aventine Hill before the sack (including Sabina?) may well have had country estates to which they could relocate. In my imagination the hill would still have been a place of ruins, perhaps with improvised market gardens or animals grazing where once there had been luxurious houses. (Note: I recently watched an interesting video on the role of population decline in the fall of the Western Empire. You can find it here.)

Looking north from the hilltop, what would one have seen? More ruins across the river in Trastevere, I suppose, and to the right on the Palatine Hill. But Rome was to suffer two more sackings in the next six decades, so it wasn’t yet as bad as it would get.

Was the Temple of Juno still standing on the Aventine Hill? As a pagan structure it would not have been afforded any special protection by the Goths, but in any case, given the suppression of the old religion by now-dominant Christianity, it might already have fallen into a state in which it wasn’t worth looting.

The Interior

Inside the Basilica of Santa Sabina, the overwhelming impression is of an austere nobility. Whenever we have been there, there have been no seats in the nave, so you really feel the space. Lining the nave are columns that were taken from the Temple of Juno and re-used. That temple was built around 400 BC and then restored during the reign of Augustus. So you are standing in a building that is over 1600 years old, but the columns are even older – I’m not an expert, but I would guess that elaborate Corinthian capitals like this would date from the Augustan restoration of the temple, making them 400 years older than most of the church.

Above the door is a dedication in Latin hexameters, which I assume is the reason we know that Peter of Illyria commissioned the church.

The windows in the apse, and in the clerestory (that is, along the top of the walls of the nave), contain neither plain nor coloured glass, but shards of a translucent mineral called selenite, mounted in delicate stone tracery. This is apparently a very ancient practice – the first use of glass in windows is supposed to have been some decades after Santa Sabina was built. As far as I can find out, this is one of the very few ancient buildings (or perhaps the only one) where you can still see selenite windows.

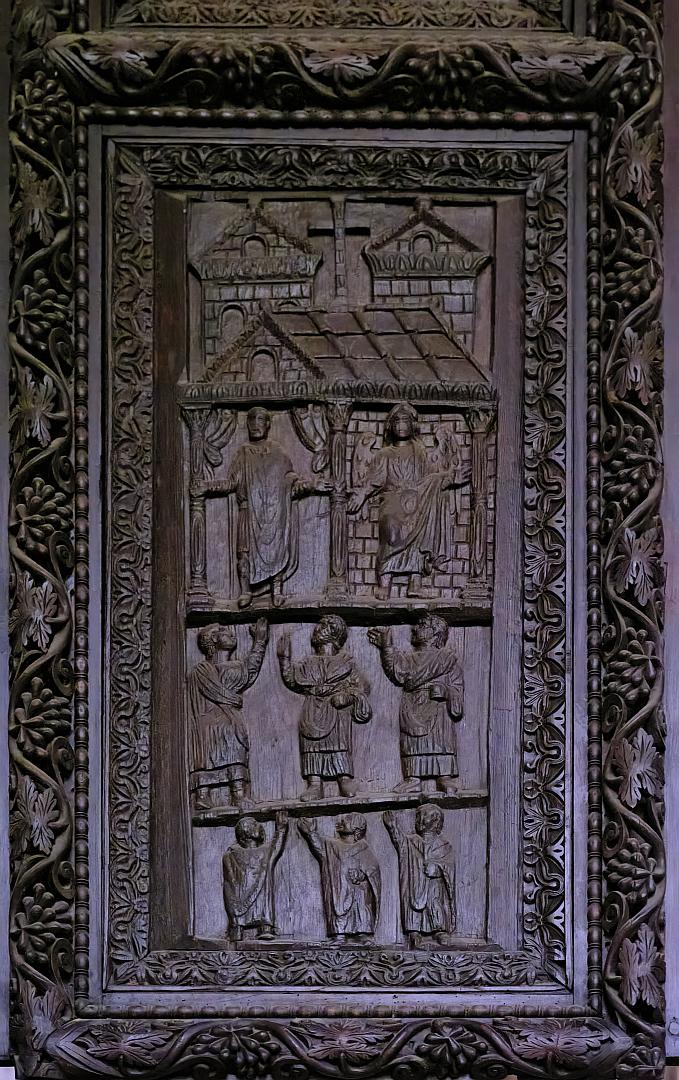

The Doors

If you get excited about unlikely survivals of really old stuff, then a highlight of Santa Sabina is seeing the original doors of cypress wood, still in position. They are huge, and are easily the oldest large wooden artefacts that survive from antiquity. Despite their being made of wood, and despite their having been exposed to the open air for around 1,600 years, you can still look at the intricate carvings of biblical scenes.

Needless to say the carvings on the doors have been the subject of intense academic study – and the inevitable disagreements – but two things stood out to me. One is a small panel at the far top left. It shows three figures with their arms outstretched, and while there are some alternative interpretations, it is hard to disagree with the conventional view that this is the earliest known representation of the crucifixion of Christ, with the other figures being the two thieves.

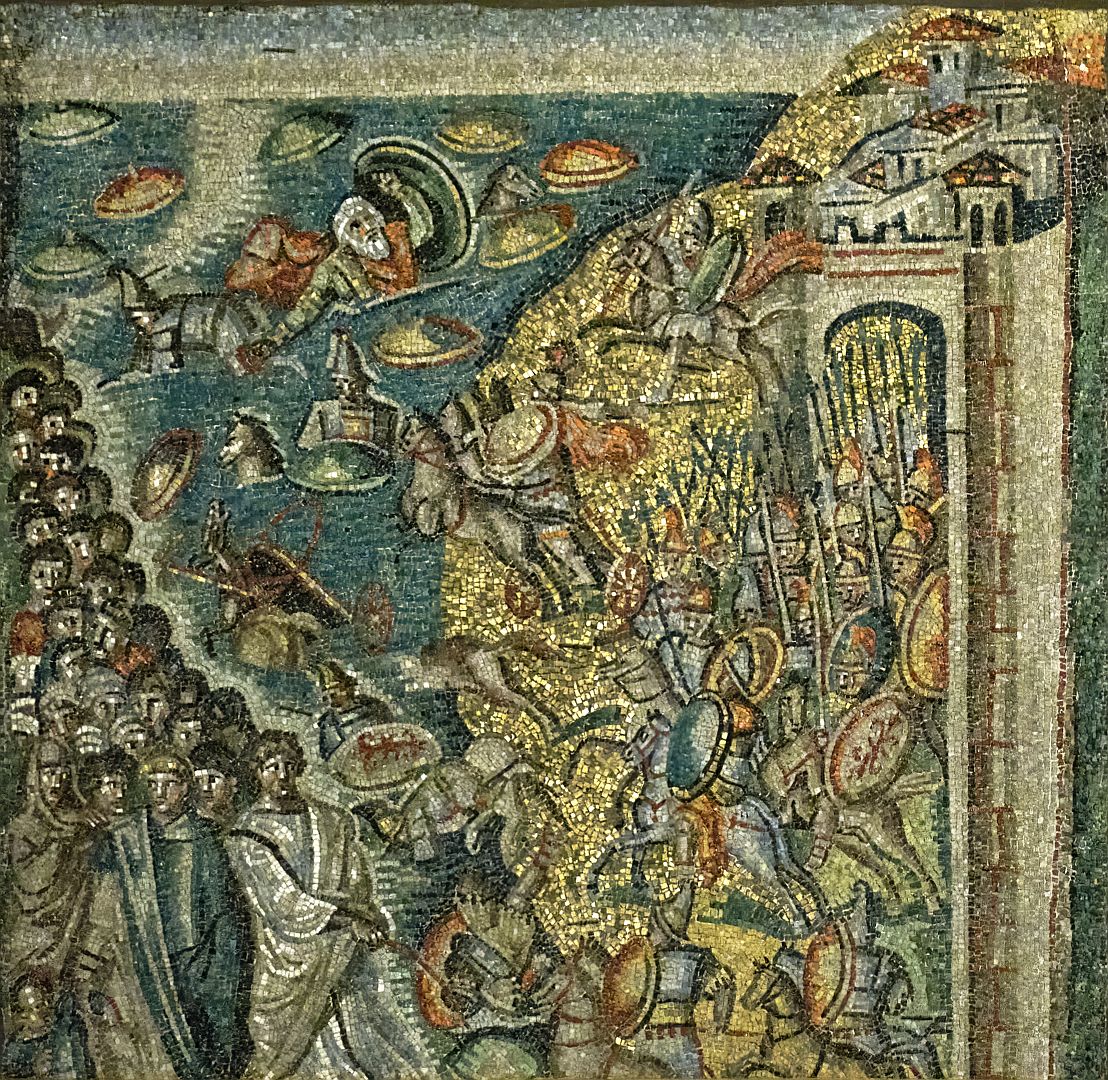

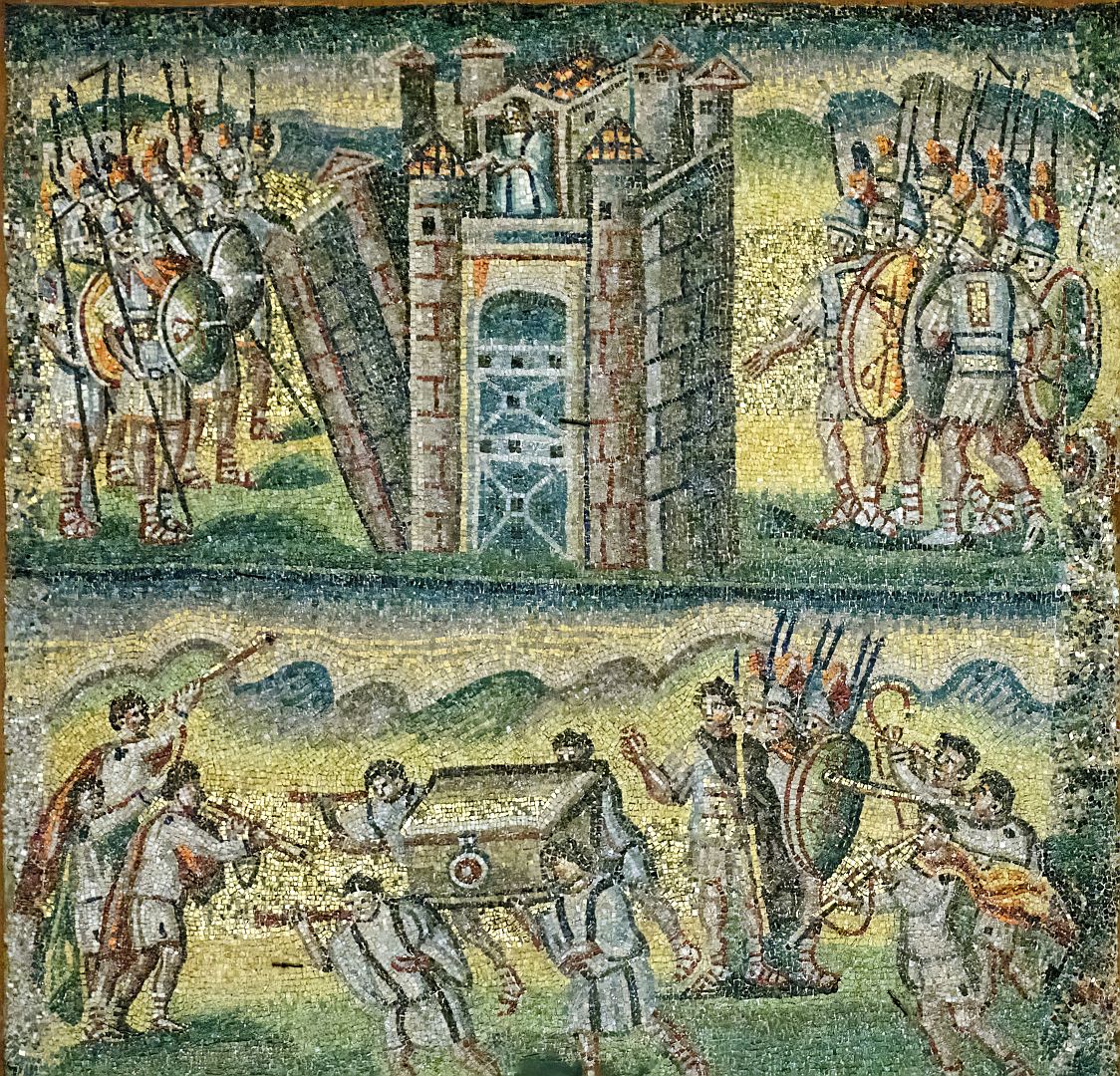

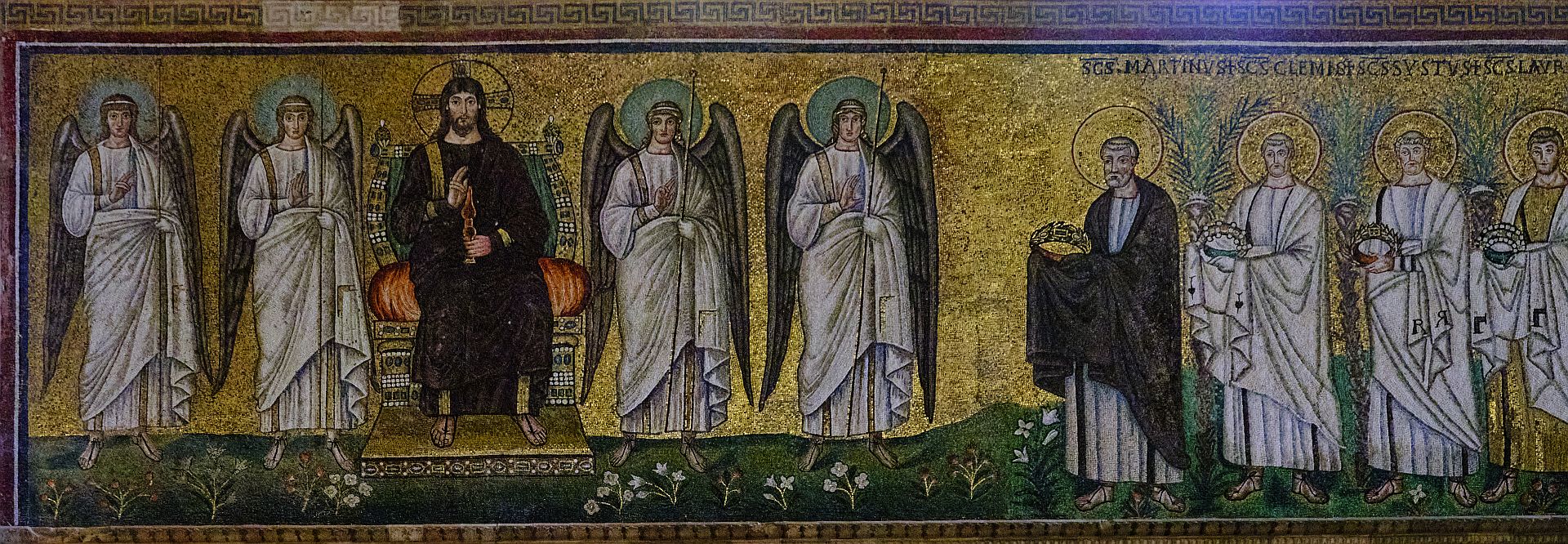

The second thing that stood out to me was the panel showing the adoration of the Magi. As in Ravenna and in Santa Maria Maggiore, our three friends are wearing diamond-patterned tights and Phrygian caps (or “smurf hats”, if you prefer). I think that puts it beyond doubt that this was the conventional representation of them in the 5th Century.

Another panel shows a figure being acclaimed by others, standing in front of a church and accompanied by an angel. While there have been various interpretations that this is a biblical event, another theory has it that the person’s costume would make him a Roman-Byzantine Emperor. If so, the most plausible candidate is Theodosius II, the Eastern Emperor at the time that Santa Sabina was built (and the nephew of Galla Placidia). Theodosius convened the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD, at which some of the thornier doctrinal questions of the early church were resolved, so you can imagine that this would have been considered worth commemorating.

Later History

The basilica survived subsequent sackings of Rome and the rest of the Dark Ages. In 1216, when the Order of the Dominicans was established, Pope Honorius granted Santa Sabina to them to use as their headquarters. Some internal redecoration occurred in the Renaissance, but the building avoided the worst indignities of the period, especially that of having an entirely inappropriate Renaissance or baroque facade stuck on the front. At one point due to fears for the integrity of the structure most of the windows were bricked in, which must have made the interior very dark.

In the half-dome of the apse there was once an original 5th-Century mosaic, which was replaced in the 16th Century by a mediocre fresco. I have not managed to find a description of the original, but it is suggested that the composition of the replacement mimics that of the original.

During Napoleon’s occupation of Rome the Dominicans were expelled, but returned afterwards. Then when the Kingdom of Italy took Rome from the Papacy in 1870 they were expelled again, and the Italian Government converted the church to a quarantine station, of all things. These days the basilica is again a consecrated church of the Dominicans.

There were two separate restorations during the 20th Century, the first of which was criticised for some of the aesthetic decisions made, including the installation of a rather bizarre pagoda-like ciborium, baldacchino or altar canopy, which was removed, along with other accretions, in the second restoration. At that time the windows were re-opened, with the stone tracery recreated based on the remains of the 5th-Century originals which had been discovered during excavations.

However if you would like to see the ciborium, and you live in California, you can do so. Someone bought it, shipped it to America and reassembled it in the grounds of the Los Angeles Forest Lawn cemetery.