Most of the visitors wandering through the Borghese Gallery in Rome probably don’t give all that much thought to the fellow who started it all – I certainly didn’t the first time I came. This is a shame, because his is an interesting if mildly unsavoury story. Visitors almost certainly give a bit more thought to a later occupant of the Villa Borghese, because she is hard to miss. But let’s start at the beginning.

Scipione Borghese

Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577-1633) embodied much that was bad, and some that was good, about the Catholic Church in the early 17th Century (anglophone art historians may call him by the Latin version of his name, “Scipio”). We will start with the bad: among his many, many, official titles, probably the most important was Cardinalis Nepos – “Cardinal-Nephew”.

You read that right. It was so common for Popes to appoint a relative – often a nephew, sometimes an illegitimate son – to high office, that it became an official position. It was assumed that the first priority of any new Pope would be enriching and ennobling his own family, so it would be best to make that a full-time job for another person. And who better to trust that job to than a family member? The English word “nepotism” was coined specifically to describe this practice.

Scipione was an actual nephew. His father was called Francesco Caffarelli, but his mother was a Borghese, and her brother, his uncle Camillo Borghese, paid for his education. In 1605 Camillo was elected Pope, taking the name Paul V. He adopted Scipione as his son, quickly appointed him a cardinal (in those days the tiresome process of climbing through the ecclesiastical ranks was optional for people with connections) and made him Papal Secretary.

Scipione acquired many jobs and titles – in locations which would have made it impossible for him to have been personally present at the same time, but that is not how it worked. If you were, for example, both Abbot of Subiaco and Archbishop of Bologna (as Scipione was), you didn’t have to be in either place. Instead you received the income but stayed in Rome and employed deputies to discharge most of the actual duties. With at least a couple of dozen such offices, Scipione quickly became very wealthy indeed. With wealth came power, and he was able to persuade a few landowners to sell significant estates to him or other members of the family on very favourable terms – by making them “offers they couldn’t refuse”. According to the Wikipedia article he purchased entire towns, and the Borghese ended up owning about a third of the land south of Rome. All the while, his uncle Paul V looked on benignly.

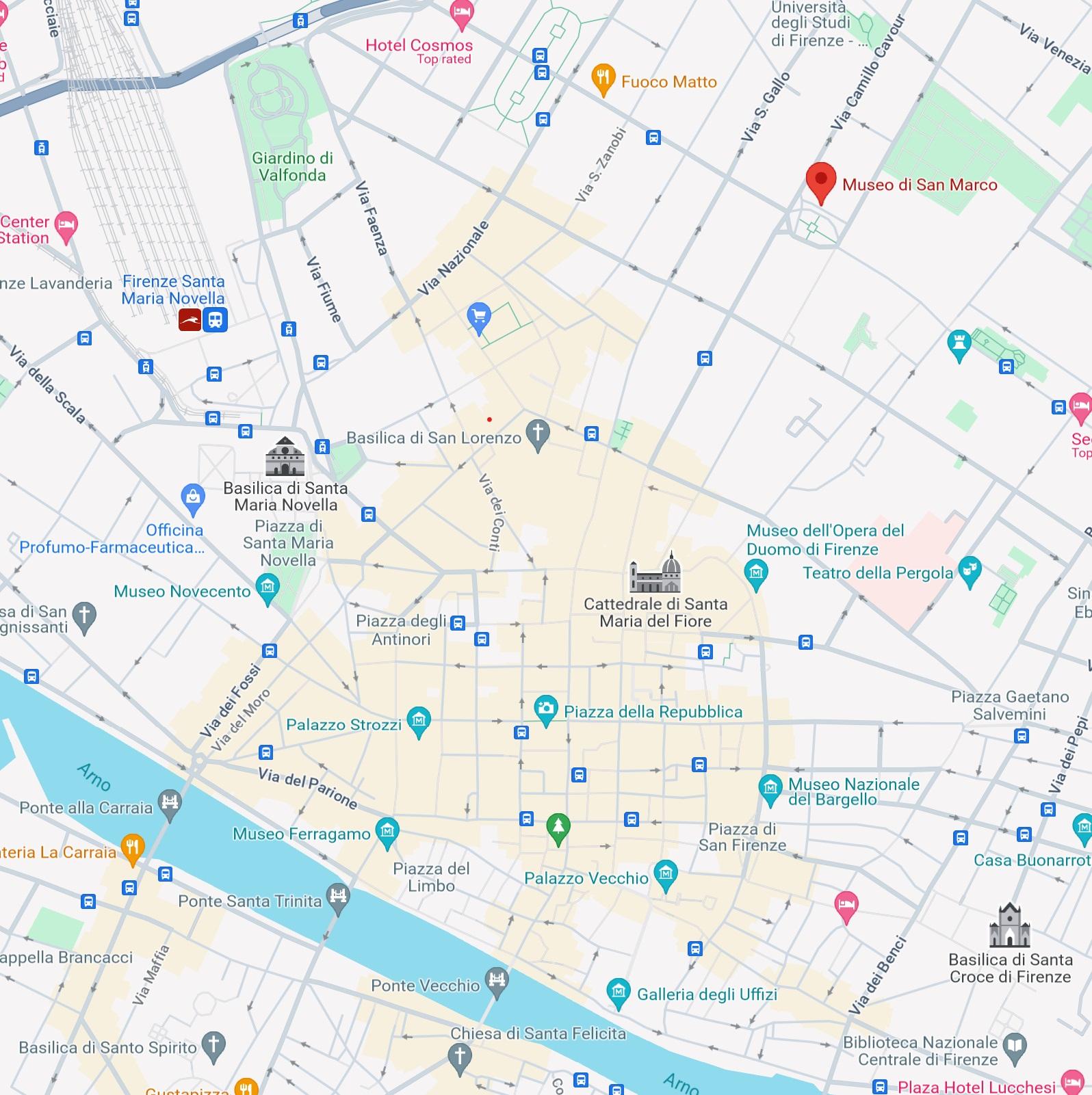

So what was the good part? His legacy of art and architecture. It seems that Scipione may not have wanted the top job for himself – he never seems to have been considered for Pope. He was an enthusiastic builder; inheriting the Palazzo Borghese in Rome from his uncle, he enlarged and modernised it. He also commissioned or modernised several churches. In architectural terms what he is most remembered for are the Borghese Gardens – a large area of former vineyards on the edge of the old city of Rome which he had developed as a park, and the beautiful villa he built there. But what he wanted to do most of all was to collect, patronise and admire art, and the Villa Borghese was – as it still is – the perfect place to house his collection.

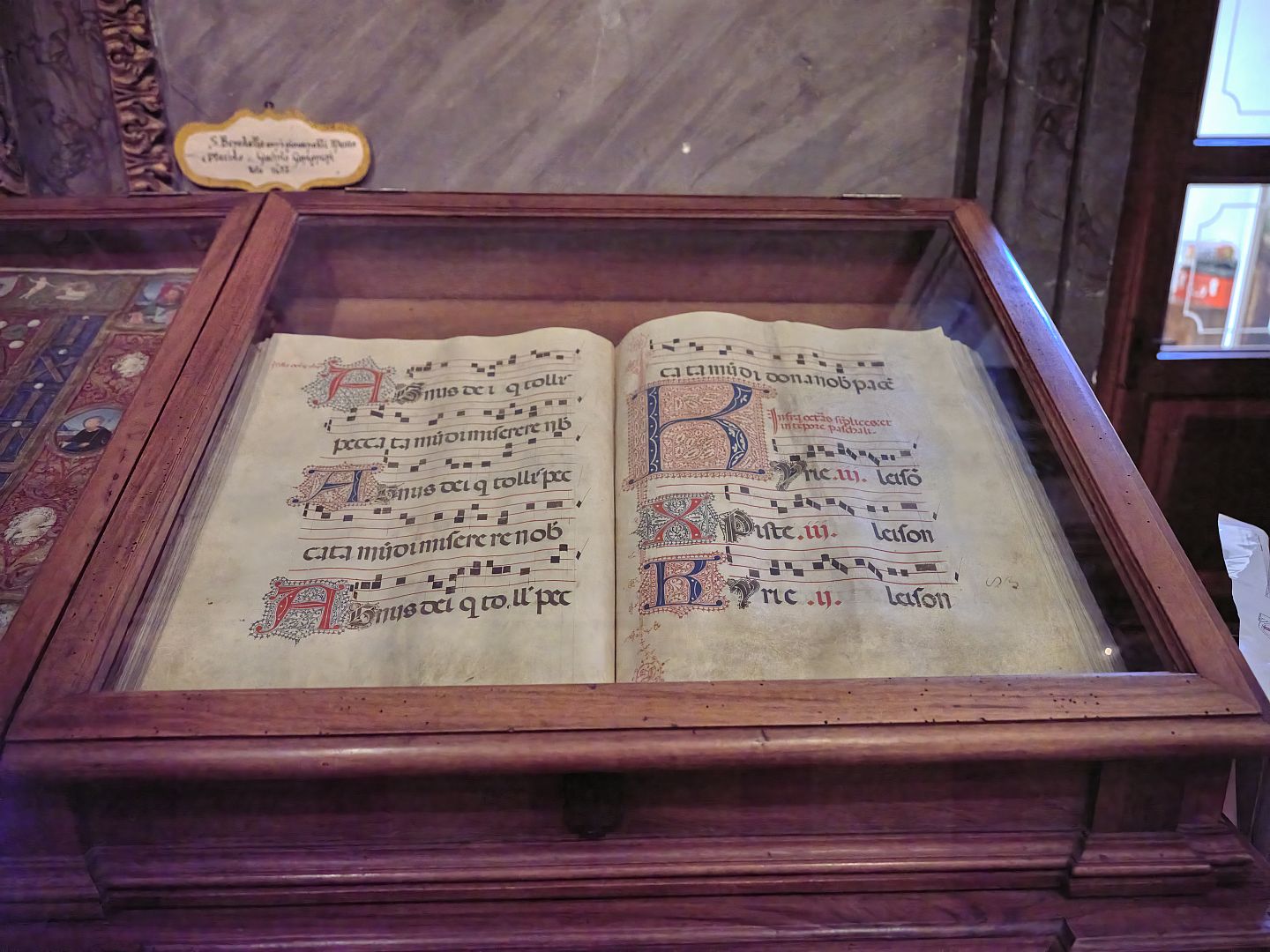

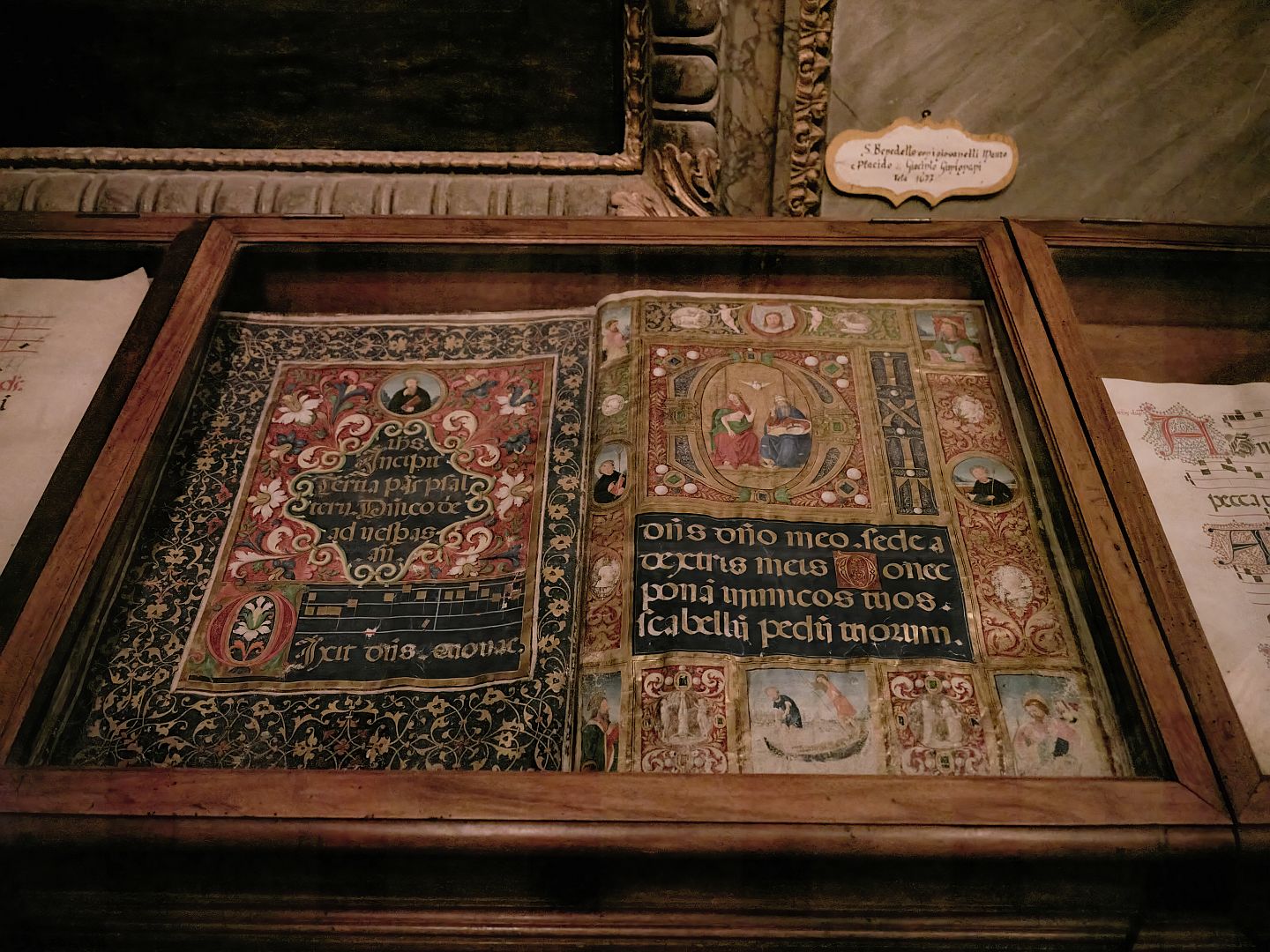

Art, Ancient and Modern

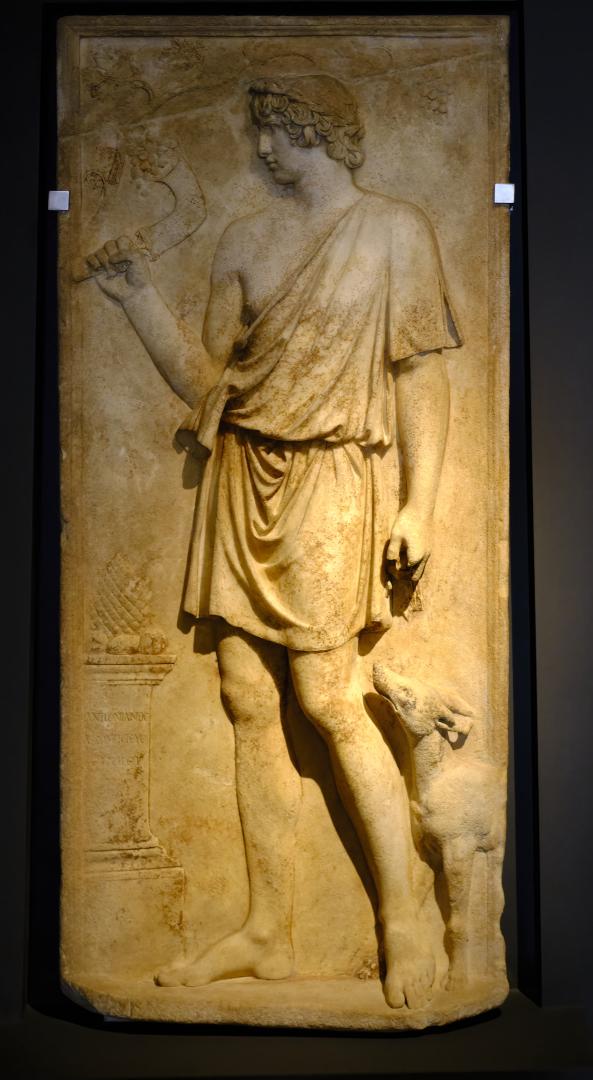

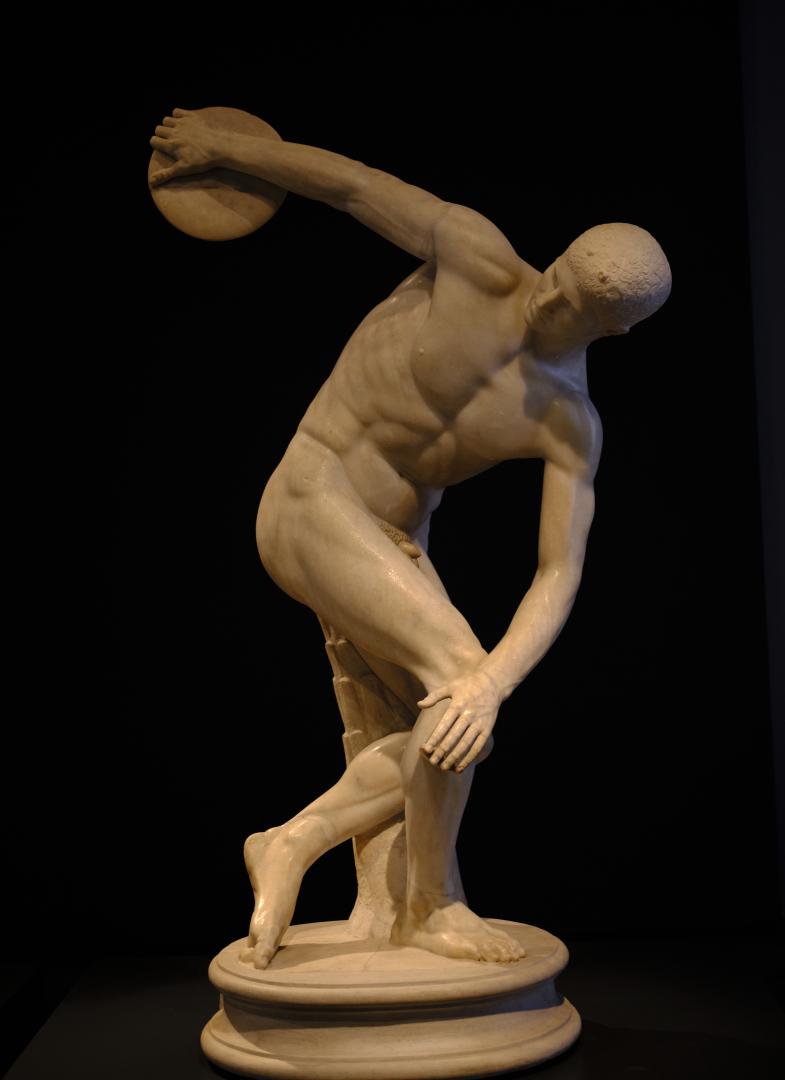

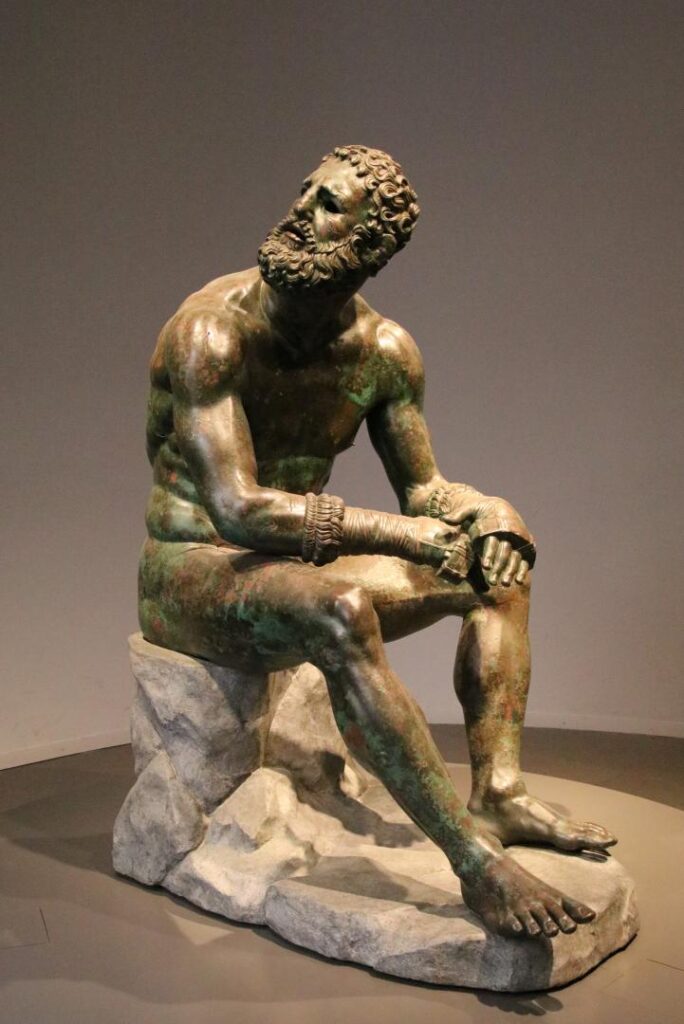

Art collecting and patronage wasn’t particularly new at the start of the 17th Century. Over a hundred years earlier the pattern of the discerning Renaissance prince had been set by Lorenzo de’ Medici (“The Magnificent”) and others like Duke Federigo da Montefeltro and Cardinal Ippolito d’Este. But Scipione seems to have taken it to a new level. In addition to art by his contemporaries, he was an enthusiastic collector of ancient Roman statuary; again this was nothing new, but the taste for collecting ancient art meant that collections were available to be bought, and new finds would be coming on the market from time to time.

Disreputable artists – Bernini and Caravaggio

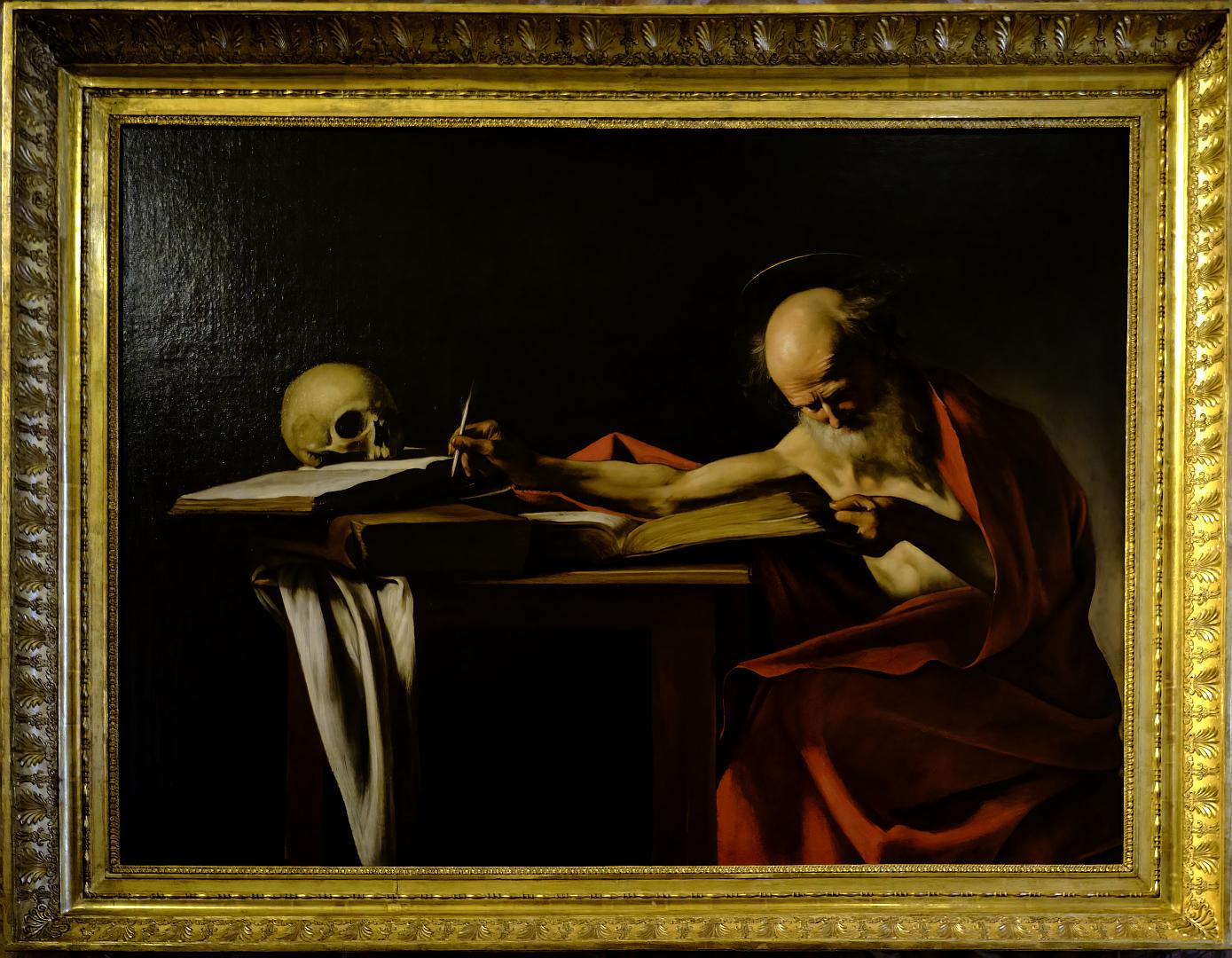

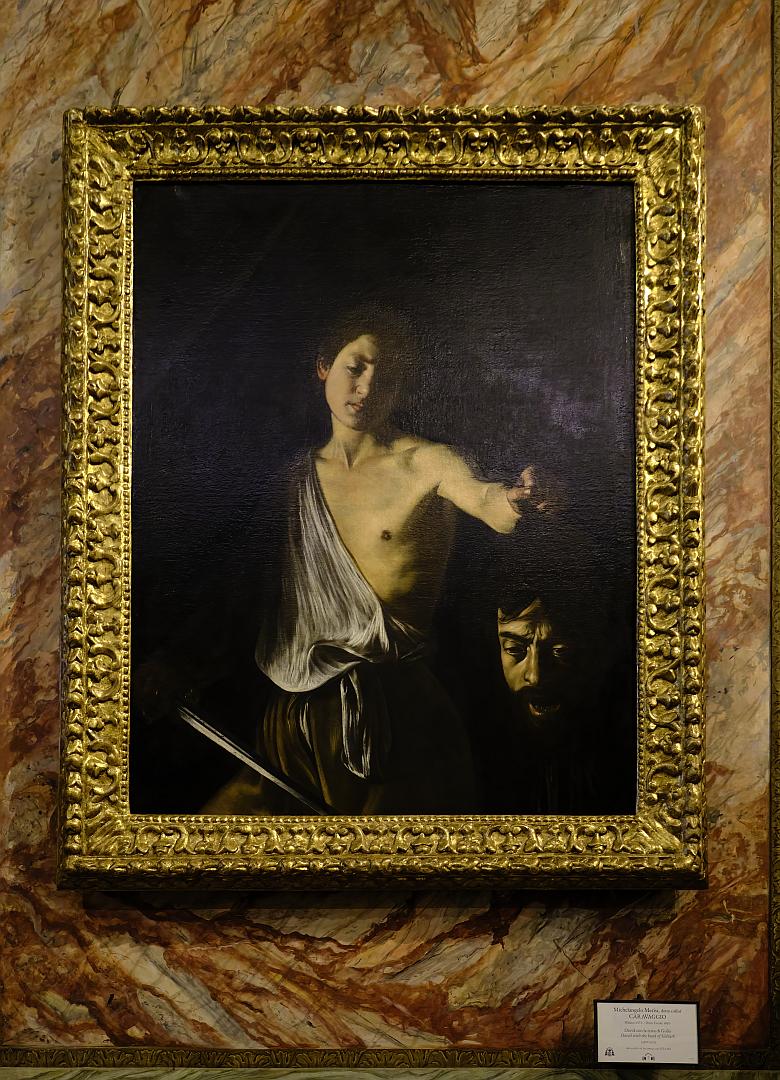

Two artists who will always be associated with Scipione Borghese are Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Michelangelo Merisi, the latter better known to history as “Caravaggio” after his birthplace in Lombardy. Both behaved reprehensibly in their private lives, but both were geniuses. It seems to me that in their virtues and their vices they represent something about the time and the place – in early 17th-Century Italy emotions were intensely felt and intensely expressed.

Bernini was recognised in childhood as “a future Michelangelo” and he certainly was – his ability to conjure life out of cold marble has probably never been matched. Both Scipione and his uncle commissioned major works from him, including the baldacchino (altar canopy) in St Peters, and the Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona.

But some of his unquestioned masterpieces are in the Villa Borghese. After the death of Paul V, the next couple of Popes continued their patronage.

The darker side of Bernini’s character was shown when he started an affair with a woman called Costanza, the wife of one of his workshop assistants. However in time Costanza also had an affair with Bernini’s younger brother Luigi, who worked in the same studio. When Bernini found out about it he attacked Luigi in a jealous rage, chasing him through the streets of Rome into Santa Maria Maggiore. Bernini then had one of his servants go to Costanza’s house and slash her face several times with a razor. The servant was jailed for the assault, and Costanza was jailed for adultery. Bernini, though, thanks to friends in the highest of places, got away with it completely. After exonerating Bernini, the Pope ordered him to marry a Roman woman called Caterina Tezio with whom he was to have 11 children, which appears to have settled him down a bit.

The overlapping worlds of art and Papal politics in Rome in the 17th Century were spiteful places. Bernini had plenty of enemies and when in time the Papacy came into the hands of a different faction, they struck. He was falsely accused of incompetence in his design for two bell towers for St Peters, which were starting to crack (subsequent investigations showed that the builder of the foundations was to blame). But he was fined a massive sum and withdrew from public life. An unfinished statue in the Borghese Gallery, titled Truth Unveiled by Time, is a work he undertook to console himself that the truth would come out in the end, as indeed it did.

If Bernini’s was the life of an artist disfigured by a crime, then Caravaggio’s was a life of crime ennobled by art. Caravaggio’s list of offences would have been as long as one’s proverbial arm, or much longer, unless it had been in very small writing, and on both sides of the page. Yet he was as much of a genius as Bernini, and even more influential. More so than any of his predecessors, he understood how light works, and his use of chiaroscuro (literally “light and dark”) transformed painting. For that reason I feel that every photographer should study him – “photography”, after all, is Greek for “painting with light”.

But if you really want to see where Caravaggio has had a great influence, look at modern cinematography. I am an inveterate watcher of films without sound, over other people’s shoulders in aeroplanes. In those circumstances one tends to notice the visual aspects, and on one such occasion it occurred to me that a film that had received much praise for its cinematography was exemplifying Caravaggio’s style very well, with extreme lighting contrasts adding drama to the plot – whatever that might have been.

When the young Caravaggio arrived in Rome – characteristically he was on the run from the authorities in Milan after wounding a police officer – he quickly came to Scipione Borghese’s attention. A couple of his early works are in the gallery, and the story of their acquisition gives us some insight into Scipione’s modus operandi. Caravaggio had been working in the studio of a man called Giuseppe Cesari, and these paintings were in Cesari’s collection. Scipione made Cesari an insultingly low offer for them, which Cesari refused. He should have realised that he was being made an offer he couldn’t refuse, because Scipione then arranged to have him arrested on trumped-up charges, and then simply appropriated the entire collection, including the two Caravaggios.

The government of the Papal States was meticulous in its record-keeping, and Caravaggio’s police interviews fill many pages. A man of fiery temper, he frequented low inns and brothels, associated with criminals and prostitutes, and was frequently arrested for brawling in the street. To make matters worse, he claimed that his status as painter to various noblemen made him a gentleman and gave him the right to wear a sword. This was not actually true, and got him arrested several times for carrying a weapon illegally. Inevitably he ended up using that sword (the quarrel was over a prostitute called Fillide Melandroni who had modelled for him) and this time he ended up on a murder charge that even his influential patrons could not get him off. He was sentenced to death by decapitation, and fled Rome with that hanging over him. It can be no coincidence that many of Caravaggio’s subsequent paintings featured severed heads – Holofernes, Goliath, John the Baptist etc – and that in some cases those severed heads were self-portraits.

To spend more time on Caravaggio’s many misadventures would take this article off in the wrong direction, so let it suffice for now to say that eventually he was able to secure the promise of a pardon from – who else? – Cardinal Scipione Borghese, and was on his way back to Rome when he died, in slightly mysterious circumstances, but probably of nothing more sinister than a fever.

Caravaggio may hold the record among great artists for the number of his paintings that were rejected. Typically he would receive a commission from a wealthy art lover for a painting of a particular subject – The Virgin and Child, the Conversion of Saint Paul, whatever – and would produce something marvellously realistic, with models who were beggars, thieves or prostitutes. The authorities in the church or institution in which the painting was to be hung would then reject it in horror. Dirty real people were not what they wanted their congregations to see. Still, there was always Cardinal Scipione Borghese to resolve the embarrassing situation by buying the unwanted picture – at a discount, of course.

Scandals

So we know that Scipione, in addition to having an eye for great art, didn’t mind associating with some of the seamier elements in society. He wouldn’t be the last wealthy and powerful person to enjoy that sort of thing. But there were other rumours too. Some see a strong homoerotic element in his choices of art, such as the Hermaphrodite, and some of the pictures painted for him by Caravaggio. I have even seen a description of Apollo and Daphne which suggests that Daphne’s transformation was a veiled reference to changing sex (I have to say that I didn’t see it myself).

But as is often the case in Italy, the best contemporary sources of rumour and gossip are the diplomatic and espionage reports which went back to other Italian states. According to these, Scipione had several homosexual affairs, and arranged for his lovers to be appointed to church offices – even to be made cardinals. There is also a shocking story about a young man who was murdered by Scipione’s servants after leaving the Cardinal’s bed.

Scipione died in 1633, aged 56, and is buried in the Borghese Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. The position of “Cardinal-Nephew” was abolished in 1692; after the Council of Trent and the Counter-Reformation, being that blatant about the material benefits of Papal office was presumably felt to be in poor taste.

Pauline Bonaparte

The Borghese family had come a long way from their middle-class origins in Siena, and Scipione had done his job as Cardinal-Nephew very well. He was an astute investor and the family’s income from their enormous property holdings meant that they would no longer be dependent on playing the risky game of Papal patronage for access to wealth and power. What is more, marriages with ancient Roman aristocratic families like the Orsini and the Aldobrandini meant they acquired those families’ fortunes as well as their princely titles.

Once such prince, Camillo Borghese, enlisted in the Napoleonic army and became a general. In 1803 he married Napoleon’s sister, Pauline Bonaparte.

Pauline had an interesting life; both her original marriage to the French General Leclerc and, after his death, to Camillo Borghese, were entered into at her brother’s direction. She accompanied Leclerc to Saint-Domingue in the West Indies (modern Haiti) where he recaptured the island after a slave rebellion, and became its Governor-General. After his death she returned to France and was then married off to Camillo in the hope of improving relations between the Romans and their French rulers (it didn’t work).

Perhaps because these were arranged marriages, it seems that Pauline felt under no obligation to remain faithful to either husband, and she acquired a reputation for promiscuity which she seems to have enjoyed. When Camillo arranged for the leading Italian sculptor of the day, Antonio Canova, to create a statue of her as the virgin huntress goddess Diana, she is said to have insisted on being portrayed as Venus because no-one would believe she was a virgin.

Since Pauline’s naked body in the statue is just a standard idealised classical nude, it is of course perfectly possible that she only posed for the sculpture of her head and face, and that Canova finished it without using her as the model. But Pauline would not want to ruin a good story any more than the rest of us would, and scandalised Roman society by insisting that she had indeed posed nude. When a shocked Roman matron asked how she could possibly have done so, Pauline replied that it had not been difficult because she had ensured that there was a stove in the studio to keep her warm.

Even though Napoleon had treated her as diplomatic currency, in the end she was more loyal to him than any of their other siblings. When he was deposed and exiled to Elba she liquidated all her own assets and moved to Elba to be near him and to use the money to improve his living conditions. After Waterloo and his final exile to St Helena, she moved back to Rome and lived out the remainder of her brief but eventful life under Papal protection.

Further Reading

I am not aware of a biography in English of Scipione Borghese (please correct me in the comments if you are). He and the rest of his family are mentioned in John Julius Norwich’s The Popes. A recent biography of Caravaggio is Caravaggio, A Life Sacred and Profane by the English art critic and TV personality Andrew Graham-Dixon, which inevitably discusses Scipione.

Christopher Hibbert’s Rome (I have the luxurious 1997 Folio Society edition) builds a whole chapter around the life of Bernini, although he omits any reference to the Costanza incident.