A visit to two different, but memorably-decorated churches in Perugia – the Oratory of St Bernardino, and the Basilica of San Pietro.

There are many excellent things to see in Perugia, and other reasons to visit too: good restaurants, not too crowded, parking fees that are not extortionate by Italian standards, and free escalators and lifts from car parks up to the historic centre. The Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria has fine examples of Umbrian Art, and the Museum of Archaeology (to be the subject of a future post) has fascinating Etruscan artefacts.

But for most historically-minded visitors to Perugia, one of the main impressions they take away with them is of the group of magnificent gothic public buildings[1] which together form the Palazzo dei Priori, at the end of the Corso Vannucci, near the duomo (cathedral) and the Fontana Maggiore. As I discussed in my post on The Buried Streets of Perugia, one reason this part of town is so well-preserved is because of the Papal conquest in the early 16th Century, and the subsequent expropriation of most revenue to Rome. The architecture stayed as it was because there was no money to change it – the money went to Rome where many fine old buildings were “modernised” in the baroque style. In architectural history, the hard times of earlier ages can sometimes be posterity’s gain.

All that being so, today I would like to talk about a couple of – in my view under-appreciated – buildings which are covered in exuberant Renaissance decoration, one on the outside, and one all over the inside. Both are in easy walking distance from the historic centre, but because the centre has so much to offer, many visitors never get to them and you can admire them in peace.

The Oratory of St Bernardino of Siena

Let us start with the one that is decorated on the outside. It is the Oratorio di San Bernardino, part of a complex which includes the larger church of San Francesco al Prato, nowadays associated with Perugia University.

Although he came from Siena, Bernardino preached all over central Italy, and was particularly active in Perugia, where you can see a special pulpit they built for him on the side of the duomo. I don’t know if non-Catholics are supposed to have favourite Catholic saints, but if I were allowed to, Bernardino would definitely not be one of mine. He preached fiery sermons against Jews, homosexuals and gypsies, sometimes leading to violence against them, and his views on women seem to have been regressive even by the standards of the early 15th Century. He is associated with the start of a period of witch-burnings that was a stain on European history for over two hundred years.

In iconography, he is always rather appropriately represented as having a pinched, disapproving face, and since this seems to be based on contemporary portraits, that must indeed be what he looked like. Anyway, I don’t want to give offence, so let us move on to the charming little oratory that the Perugians started building in his honour in 1452, only eight years after his death and two years after his canonisation.

It seems that Bernardino is credited with having pacified the warring factions in Perugia (see my post on Tough Guys in Art – the Baglioni of Perugia) and it is for this reason that he was popular there.

To complete the building, the Perugians commissioned a Florentine sculptor called Agostino di Duccio to create a façade in polychrome, showing The Glory of St Bernardino.

And glorious it is, with cream and pink marble, and blue lapis lazuli creating a most agreeable pastel effect. Apparently there was gold there too once, but whether this was deliberately removed or just flaked off I don’t know. It must have been magnificent when new.

At the top there is a Virgin and Child, below which you can see the words AUGUSTA PERUSIA, the title given to the city in antiquity by the Emperor Augustus (see my post on The Ancient Gates of Perugia) and the date 1461, when the façade was completed.

In the centre, we see the saint surrounded by angels, below which is a frieze commemorating the attested miracles that would have been needed for his canonisation. That is also where the sculptor signed his name – OPUS AUGUSTINI FLORENTINI LAPICIDAE.

My favourite parts are the panels either side of the two doors, where there are several angel musicians. Most of the musicians are showing the expected decorum, but one seems to be auditioning for the role of lead guitarist in a thrash metal rock band.

Inside the church is a complete contrast; very simple and austere. I don’t know if it has always been thus, or whether, as in so many cases, a modern restoration has removed baroque accretions to bring back the dignity of the original. But if baroque excess is your thing, there is a chapel behind the altar you should visit.

The altar itself is a Christian sarcophagus of the late Roman period. It was re-used to house the remains of Giles of Assisi, one of the companions of St Francis.

On the wall you can see hanging a gonfalone or banner, commemorating the deliverance of Perugia from an outbreak of plague in 1464. The Madonna is shown protecting the city from divine wrath in the form of two armed angels and a particularly angry-looking Christ. At the bottom, another armed angel (I think it is the Archangel Michael) is driving away the figure of death with a spear. The interceding saints are on either side of the Madonna, with St Bernardino at the lower left. You can see what I mean about his pinched face.

The Abbey Church of San Pietro

This basilica, to the south-east of the historic centre of Perugia, is most definitely not a Renaissance building. Parts of it date from the 10th Century, replacing a 4th-Century church which was in turn erected on an Etrusco-Roman religious site. It was the church of a wealthy and powerful monastery (now the department of agriculture and environmental science at the university).

It has a distinctive tower on a 12-sided base, dating from the 13th Century, long a Perugian landmark. In fact in the National Gallery of Umbria there is a series of 15th-Century paintings by Benedetto Bonfigli showing incidents in the life of the Patron Saint of Perugia, St Herculanus, ending with the transfer of his remains to San Pietro. Despite Herculanus having been an historical figure from the 6th Century, Bonfigli charmingly paints it all as having occurred in the Perugia of his own day, in which the tower of San Pietro is easily identified.

It seems that like many powerful monastic establishments, the Abbey took sides in secular conflicts, which sometimes saw it being attacked, damaged and restored. In the 16th Century a period of reconstruction and decoration of the basilica began which continued into the 18th, and in the course of this every single available surface was covered in frescoes, oil paintings and wood carvings. Although the quality of the art is variable, the overall effect is overwhelming.

Behind the altar, the choir stalls are of intricately carved and inlaid wood, with many grotesque – and distinctly non-religious – subjects.

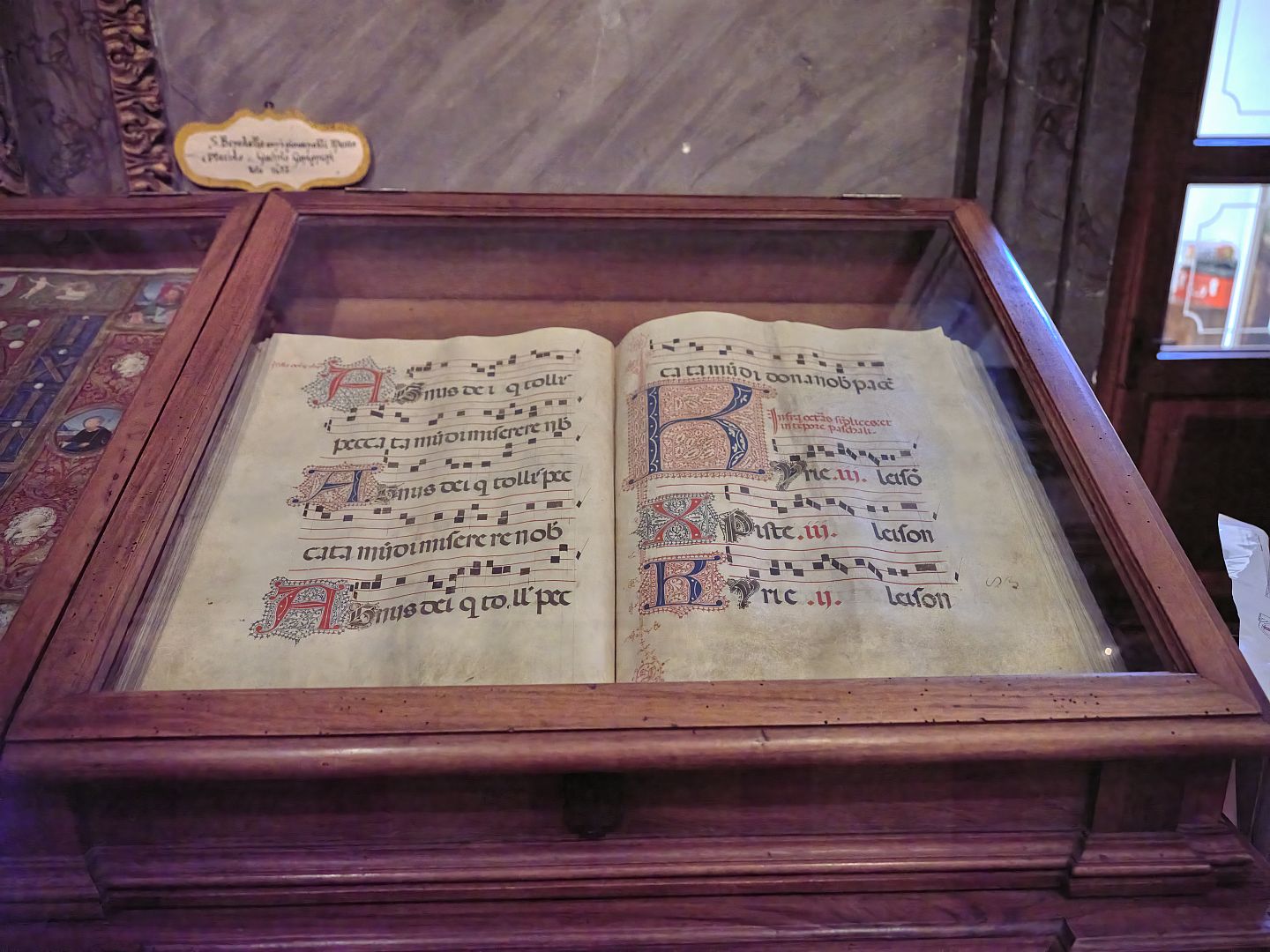

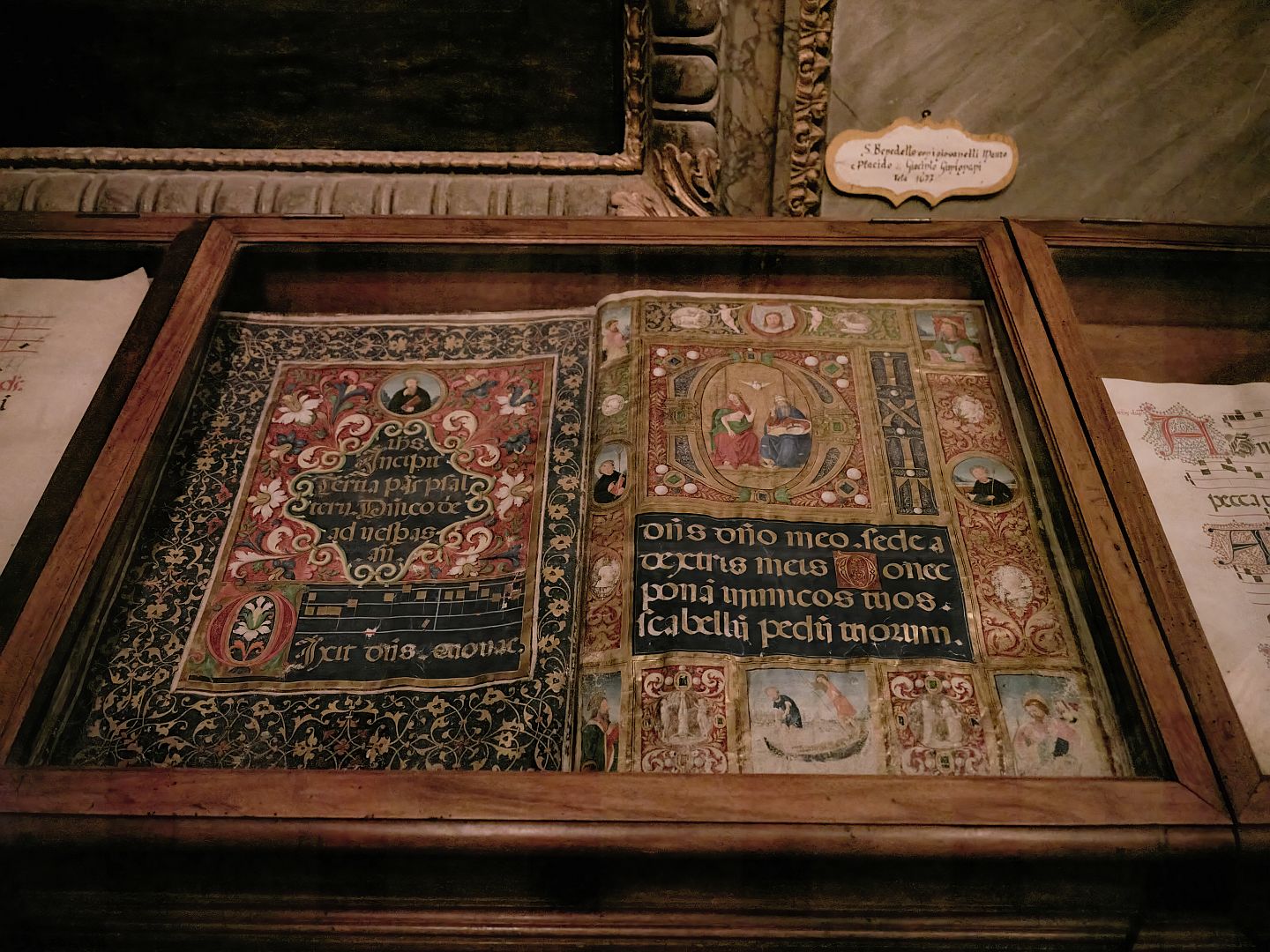

The church also holds a collection of manuscript volumes of Gregorian Chant, some beautifully illuminated.

In 2022 we attended a performance here of Claudio Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 by a group from Monteverdi’s home town of Cremona. It was beautifully performed, and in a most evocative setting.

[1] Note: in architectural terms, “gothic” refers to the style of the late Middle Ages, characterised by pointy window arches and other decorative features. It has nothing to do with the Goths, confusingly.