Venice is full of of little curiosities which reward keen-eyed and historically-minded visitors as they flee into the dark alleys away from the heaving crowds in the Piazza San Marco, or the souvenir sellers on the Riva degli Schiavoni.

You can see the commemorative plaque on the wall of a house from which, in the year 1310, an old lady dropped a mortar on the head of the standard-bearer of the would-be coup d’état leader Bajamonte Tiepolo, killing him on the spot, and foiling the rebellion. Or one of the little courtyards named del milion after one of its inhabitants, Marco Polo. Apparently people got so tired of his boasting about the fabulous wealth he had enjoyed in the East that they gave him the nickname milion.

Try not to drop the True Cross in the canal

I have a couple of other examples for you. Let us start in the Accademia gallery, with Gentile Bellini’s painting, executed around the year 1500, of The Miracle of the True Cross at the Bridge of San Lorenzo.

Small pieces of wood, purporting to be fragments of the True Cross (ie the cross on which Christ was crucified) were especially venerated in the Middle Ages. There were quite a few of them – perhaps enough for several crosses. A particularly precious fragment found its way into the possession of the post-crusader kingdom of “Cyprus and Jerusalem” in the mid-14th Century. By that time of course, it was only Cyprus, as Jerusalem had been lost to the West for all practical purposes almost two hundred years earlier.

Cyprus itself became an effective Venetian colony, through some typically tough Venetian realpolitik involving a young Venetian lady named Caterina Cornaro, who became Queen of Cyprus. Hers is a sad and romantic story, and I should write a separate post about her one day. But one of the items of treasure which found its way from Cyprus to Venice in that period was the fragment of the True Cross, which in 1369 was donated to one of Venice’s religious-commercial brotherhoods, in this case the Scuola of St John the Baptist.

Soon after its arrival in Venice, the relic in its elaborate reliquary was being taken through the streets for public veneration in its annual possession. Unfortunately, as the procession crossed the bridge over the San Lorenzo Canal, it fell in the water. Various members of the scuola dived in after it, but the relic mysteriously evaded efforts to retrieve it, until the head of the scuola himself entered the water.

As miracles go, it doesn’t seem to have involved a conspicuous suspension of the laws of nature, but an attested miracle associated with a relic was thought for obvious reasons to confirm the relic’s authenticity. So a miracle it became.

A century and a bit later, the scuola commissioned a series of paintings from leading artists of the day, including Perugino and Carpaccio, of miracles attributed to the True Cross. Gentile Bellini (1429-1507) got the commission for the San Lorenzo incident. In the picture below you can see the procession, halted on the bridge, the unsuccessful rescuers sloshing about in the canal, and the head of the brotherhood holding up the relic. To the right, an African, possibly a domestic servant, prepares to jump in and help, and the praying lady in black at the far left is thought to be Queen Caterina.

Now leave the Accademia with the picture fixed firmly in your mind, or even better, buy a postcard of it in the gift shop for reference purposes. Head eastward, past the Piazza San Marco, crossing a couple more canals, until you get to the Rio Di San Lorenzo. Cross the canal at the Ponte dei Greci, stop halfway across, and look north. That is where I took the photograph below, approximately 520 years after Bellini painted it. But it is recognisably the same place!

There are a couple of nice canal-side trattorie by the bridge; after your exertions you could do worse than stop there for an Aperol Spritz and imagine Bellini’s scene around you.

Graffiti was a problem a thousand years ago too.

After your drink, keep going in the same direction, away from St Mark’s and towards the Arsenale. This famous shipyard, the name of which became synonymous with military industry, was the wonder of its age, in which a ship could be rapidly built to a standard pattern. On one famous occasion a visiting King of France was shown the laying of a keel first thing in the morning, and the completed and fully-crewed ship sailing out through the gate that same evening. These ships were used for trade in time of peace, but could be rapidly converted for war, giving Venice access to a sizable fleet when it was needed, without the expense of maintaining it when it wasn’t.

We’ll come back to the Arsenale, but first I should mention another Venetian habit. Since Venice adopted St Mark as its patron, the evangelist’s symbol of the winged lion became Venice’s symbol. It is everywhere in the Veneto, and I still remember the thrill I felt on my first visit when I saw my first winged lion – albeit somewhat prosaically on an overpass as the emblem of the regional motorway maintenance organisation.

Venice itself has stone lions by the hundreds, many locally carved and resting their right paws on a book with the words spoken to St Mark by an angel: “Pax tibi Marce, evangelista mea” (Peace unto you, Mark, my evangelist). One of the fiercest-looking lions is on the gate of the Arsenale, in one of the first pieces of Renaissance architecture in the city, executed by the artist Gambello in commemoration of the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 (the Renaissance came late to Venice). Famously it doesn’t feature “Pax tibi…” as those words were felt a bit too pacific for such a martial institution.

But not all the lions were home-grown. As Venetian merchants roamed the Middle East, they developed the habit of souveniring any stone lions they came across. Some were much older than Venice. The lion on top of one of the two columns by the Doge’s Palace came from ancient Persia, although the wings were added after its arrival in Venice.

One such peripatetic lion, which ended up as one of a group outside the Arsenale gate, arrived in Venice from the Athenian port of Piraeus in 1687, during the campaign in which a Venetian cannon ball blew up a Turkish ammunition dump, unfortunately located in the Parthenon. But the lion was extremely ancient even then, having guarded Piraeus since antiquity.

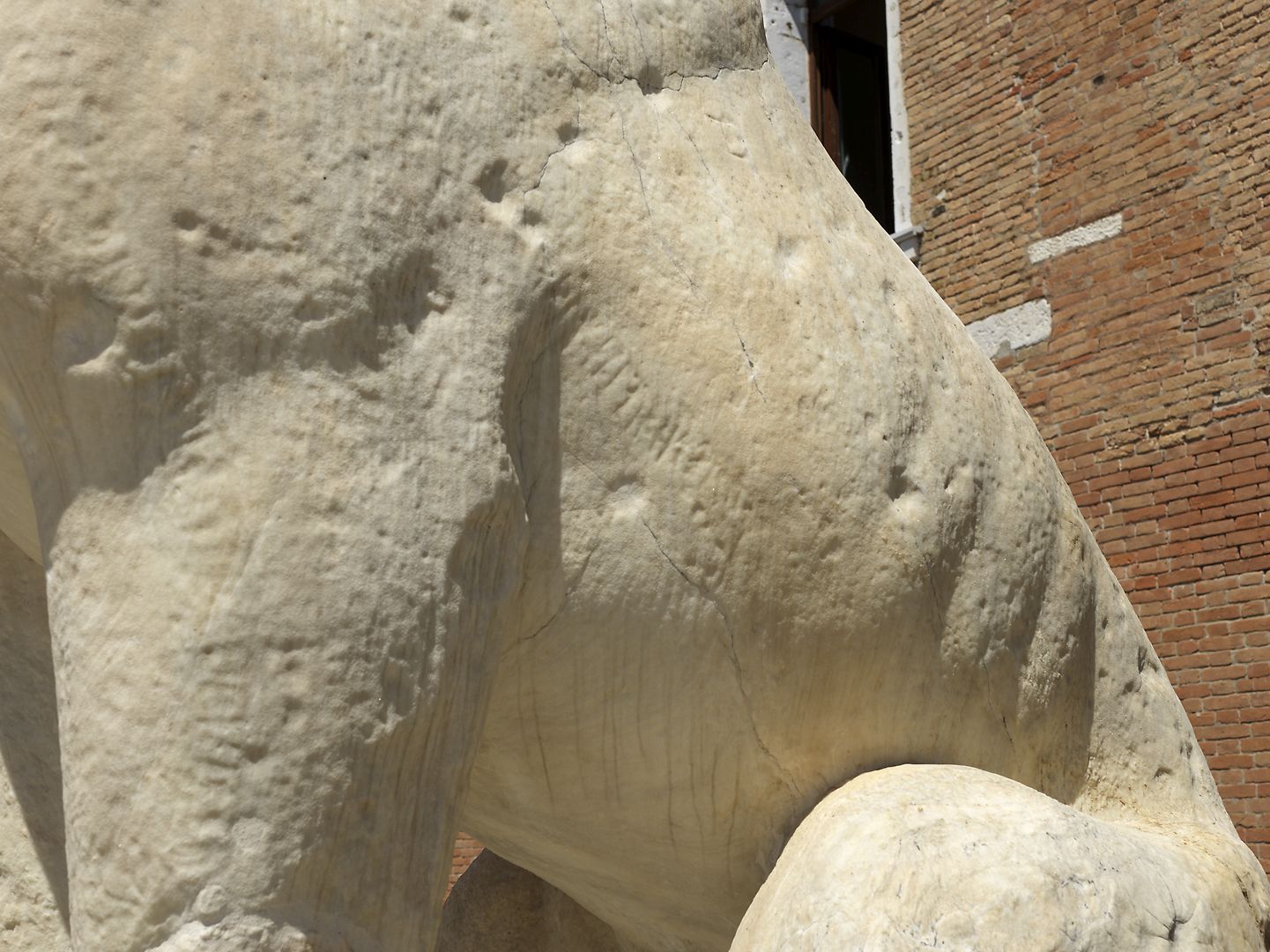

On arrival it was seen to have some strange characters – not Greek – engraved on its flanks. These remained a mystery until a visiting Danish scholar in the 19th Century recognised them as Norse runes. They turn out to have been carved on the instructions of a Norwegian mercenary called Harald the Tall who fought in various Mediterranean campaigns in the 11th century, and who died in 1066 fighting the Saxons at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, just before the Battle of Hastings. The inscription records the fact that Harald had captured Piraeus, and mentions the activities and locations of various of his companions.

At this point I can do no better than to quote from Jan Morris’s Venice:

“And on the right haunch of this queer animal is inscribed, in the runic: ‘Asmund engraved these runes in combination with Asgeir, Thorleif, Thord, and Ivar, by desire of Harald the Tall, although the Greeks on reflection opposed it.’ What all this means, only the lion knows: but modern scholars have interpreted its general sense as implying that Kilroy, with friends, was there.”

It is almost too much for the history enthusiast to take. Ancient Greece! Viking Mercenaries! The Battle of Lepanto! You probably need another drink and a bit of a sit-down. Fortunately there is another trattoria opposite the Arsenale gate.