More photography of the UNESCO sites in Ravenna, and an introduction to an intriguing lady – Galla Placidia.

Back in 2020 I posted this article on Ravenna at the Fall of the Empire and illustrated it with photographs I had taken in 2008. I won’t repeat too much of that content here, so I do recommend you have a look at that article if you are interested in the history of Ravenna, and how it came to contain so much extraordinary late-Roman art.

But for those who don’t want to, here is a very short version: Ravenna became the capital of the Western Roman Empire shortly before it fell. It was ruled by the Goths for a while, then retaken by the Eastern Empire, under the Emperor Justinian and his general Belisarius.

There are some new historical subjects covered in this post, so feel free to scroll past the photographic stuff.

Photography Stuff (feel free to skip)

Those 2008 photographs were taken with a Hasselblad 501C/M camera with a 120 rollfilm back, on slow ISO 50 Fujichrome Velvia film. When I got back to Australia I scanned the 6x6cm positives on a Nikon Coolscan 9000 film scanner. All of that presented some challenges, due mainly to the slow film in dark indoor settings. I needed to use exposures that were on the long side for hand-held photography (tripods are of course not permitted in the Ravenna UNESCO sites), which limited me to places where I could brace the camera, for example against a column. It also tended to produce colour casts, as Velvia is a film that was developed for outdoor light conditions.

Recently (June 2023) we revisited Ravenna, and this was an opportunity to re-take some of those photographs, and to take new ones in places where photography had been impossible last time due to the slow film and poor light. This time I took my Fujifilm GFX 50R medium-format digital camera, which gave me some advantages. One is that, unlike with a roll of film, one can change the ISO with every image, thus being able to shoot in low light. And while high ISO will produce electrical noise (a bit like grain in film, but in this case variation between adjacent pixels), the large sensor reduces the effect of that, simply by having smaller and more numerous pixels relative to the image size. I also used software called Topaz DeNoise AI to reduce the amount of noise further. In post-processing I was also better able to manage the colour balance.

All that being said, there are some very interesting historical things to talk about in this post, so let’s get started.

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia

On your way into the Basilica of San Vitale, you pass a small rather nondescript building which might have passed for a public lavatory or electricity substation, had they had such things in the 420s. It is the “Mausoleum” of Galla Placidia, although her body never lay here.

In my earlier post on Ravenna I made a comment that a lot of the late emperors were gormless nonentities. That was a bit of a generalisation, but quite a few of them were. One of the stronger characters of this era, though, was not an emperor but the daughter of one, the half-sister of two others, the wife of a fourth and the mother of a fifth, in whose name she ruled the Western Empire as regent during his childhood. Her name was Galla Placidia.

Placidia’s father was the emperor Theodosius I, who was not gormless, He was the last to rule both the western and eastern halves of the empire, and did a creditable job militarily despite having been given a very challenging strategic environment to work in.

Born in Constantinople, as a young teenager Placidia was summoned to her father’s court in Mediolanum (Milan), shortly before his death.

On Theodosius’s death, the empire was divided in two and he was succeeded in the west by his son Honorius, who was definitely one of the gormless ones. Faced with a military situation as bad as that faced by his father, Honorius managed to make it worse by falling out with and then executing his most competent general, Stilicho. That left Alaric, king of the Goths, as the main military force in the West. Alaric could have ended up as Rome’s greatest ally and its saviour – all he wanted was land for his people and to command Rome’s armies, which on the evidence he would have done very well. But Honorius managed the relationship so badly that Alaric ended up as Rome’s implacable enemy.

Alaric invaded Italy and laid siege to Rome, where the eighteen-year-old Placidia was then living. Somehow – perhaps while trying to escape – she was captured by the Goths and kept as a hostage in their camp. Alaric then besieged Ravenna, where, during a truce for negotiations, Honorius treacherously ordered an attack. Alaric, clearly deciding that he had had enough, returned to Rome, where he captured and sacked the city. Then, loaded with booty and even more hostages – but still including Placidia – the Goths continued south, hoping to settle in Sicily.

That would have had momentous consequences for Italian history, but instead Alaric soon fell ill and died, and was replaced by his brother-in-law Athaulf (or Ataulf). Athaulf decided instead to leave Italy and led his army, hostages and all, into what is now France and Spain where in one of the more surprising developments in an age of surprises, Placidia married him.

Why? Was it a forced marriage? It does not appear so. Was she a headstrong young woman following her heart? Was it a negotiated arrangement between Athaulf and Honorius to create a dynastic link? It seems unlikely. Was she, as an emperor’s daughter, placing herself in a position of power? History is frustratingly silent, which of course has allowed some modern writers to project their own preferences onto that partly-blank canvas.

Placidia and Athaulf had a son, who died in infancy – another fascinating what-if, for what might have become of a child with Roman imperial and Gothic royal blood? Before long Athaulf himself was murdered, and after a period of turmoil she was lucky to survive, his widow was returned to Honorius under the terms of a treaty. Honorius forced her into a marriage with his general Constantius, who shortly after was raised to the status of co-emperor. Placidia bore him two children, a girl and a boy, but was soon widowed again.

In due course her son Valentinian was declared Emperor of the West, and Galla Placidia became regent until he came of age, ruling skilfully. Indeed she has been described as the last competent ruler of the Western Empire (Valentinian having inherited the gormless gene). Her daughter Honoria became notorious in her own right for opening a correspondence with Attila the Hun (and even possibly contemplating marriage with him).

In her later years Placidia was known for commissioning churches, and one of those, of course, was the little chapel in Ravenna, now known incorrectly as her mausoleum.

What is beyond doubt is that inside the modest exterior is a little jewel box. The ceiling is covered in stars with the symbols of the four evangelists in the corners, there is a youthful beardless Christ (typical of the 5th Century) as a shepherd, and an image of St Lawrence, to whom the chapel was probably dedicated, with his gridiron.

It is not known who was buried there, but it certainly wasn’t her – she died and was buried in Rome. Nonetheless the medieval tradition that she was buried there was very strong. Someone even invented a story to explain the lack of her body in any of the sarcophagi – supposedly some children accidentally set fire to it! But the chapel definitely has a connection with her, and so we can think about her as we contemplate it.

There is no artificial light, and very little light enters – the tiny windows are covered in sheets of translucent stone – alabaster, I read somewhere. It takes a while for your eyes to become accustomed to the darkness, and even pushing the GFX50R to ISO 12800 produced some very marginal images that required a lot of post-processing. But at least I got some photographs – it was far too dark for my ISO 50 Velvia film back in 2008.

Apparently there is archaeological evidence that the little chapel was once part of a larger complex of religious buildings associated with the imperial palace.

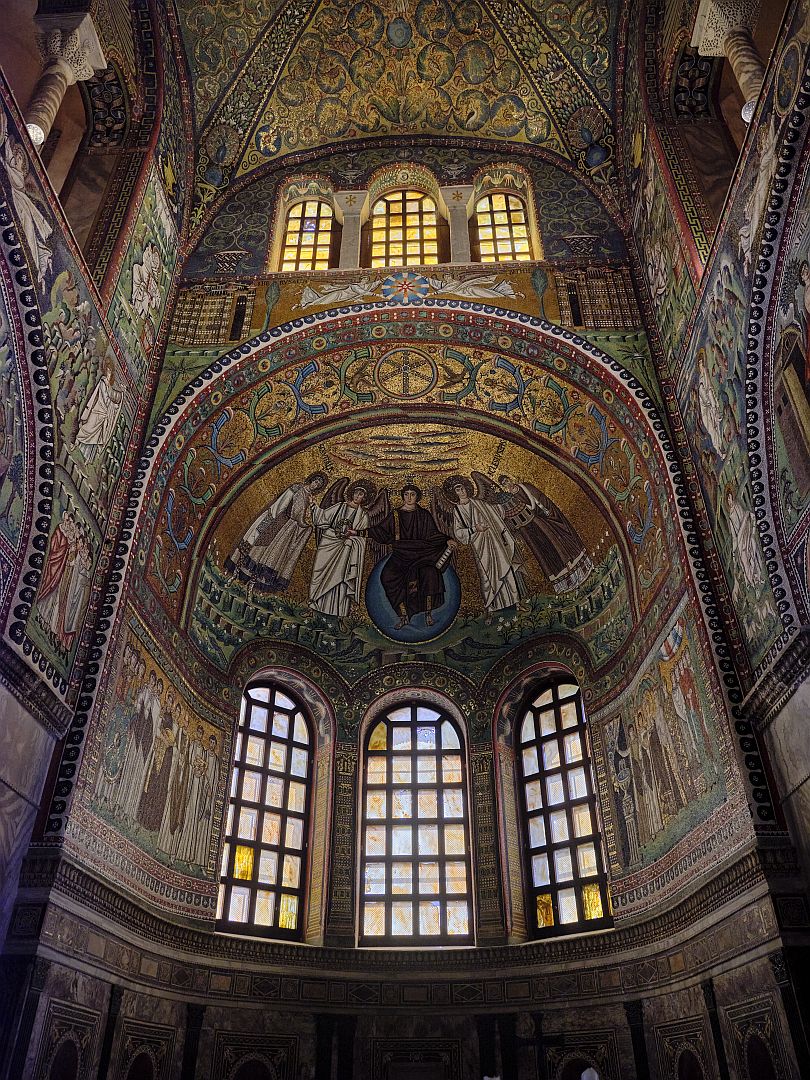

The Basilica of San Vitale

Emerging blinking into the sunlight, I had a brief conversation with the attendant who, it turned out, was a camera enthusiast and another Fuji user. From there it was a very short walk to San Vitale – built more than a hundred years after Galla Placidia’s Mausoleum.

I don’t propose to repeat everything I said in the original article but the very short version is that the building of the basilica was funded by a wealthy Ravennate starting in 526, by which time the Western Roman Empire had gone, never to be restored. It contains many extraordinary mosaics, but the two most important historically are one of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian and his retinue, and on the opposite wall one of the Empress Theodora, and hers.

We know that the bald chap is Bishop (later Saint) Maximianus, because it says so. It is also believed that the bearded fellow with the mod haircut to Justinian’s left is the great general Belisarius, hero of the first Gothic War. I have seen a few illustrations of Belisarius, doubtless all based on this mosaic, and they always manage to make him look a bit like Pete Townshend from The Who. According to the Wikipedia article, the wealthy Ravennate who funded the building of San Vitale – one Julius Argentarius – may appear as one of the courtiers in the Justinian mosaic. If that is true, then my bet, based on no research whatsoever, is that he is the thickset fellow with a five-o’-clock shadow between Justinian and Maximianus. I have also seen this described as a portrait of Justinian’s other general Narses, but find that a bit implausible, because Narses was a eunuch and unlikely to have a moustache.

I can’t remember seeing anything that suggests identifications for Theodora’s attendants, but looking at them it seems likely that the two men and two women on either side of her are intended to be actual people, given the individuality of their portraits, while the ladies off to the right are all a bit generic.

Congratulations to Lou for noticing that on the hem of Theodora’s cloak you can see a version of the Three Kings from the Church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo (see below). I had not noticed that before.

One thing that I hadn’t really thought through before was the chronology of the building of San Vitale relative to that of the Gothic Wars. When the building was commissioned, Ravenna (and indeed most of Italy) was ruled by the Ostrogothic king Theodoric, albeit notionally as a fief of the Eastern Empire. By the time that the mosaics of Justinian and Theodora were created, the first Gothic War was over and direct imperial rule had been established in the form of the Exarchate of Ravenna. Justinian was now the actual rather than the nominal ruler, and it was all thanks to Belisarius, so it is no surprise to see them both commemorated in this way. Nor is it a surprise to see Theodora there as well, as she added quite a bit of steel to Justinian’s already fairly hardline regime.

Alas, the Goths revived under the leadership of Totila, and as I have described elsewhere, the Second Gothic War, along with a couple of natural disasters, saw the complete devastation and impoverishment of Italy.

Compared to my 2008 pictures, these show the advantages of having been shot with higher ISO, and better colour balancing.

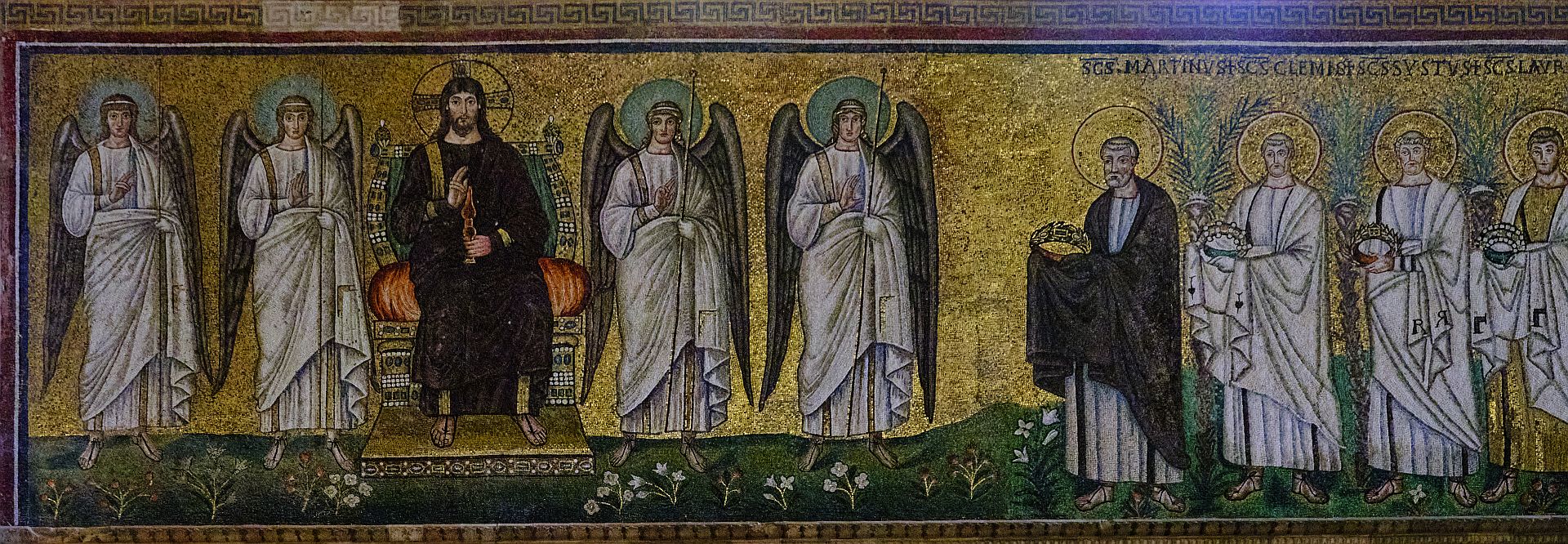

Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

From San Vitale we walked to the great church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo. Again, I won’t repeat the full description in the earlier article but this large church, like San Vitale, was started under Ostrogothic rule and was probably attached to the palace of Theodoric. As such it contained various portraits of Theodoric and churchmen who, like the rest of the Goths, adhered to the Arian version of Christianity which was later suppressed as heretical by the Catholic Church (the argument was over just how human or divine Christ actually was). At that time the “heretical” portraits in Sant’Apollinare were covered over, although they missed a few bits.

The glory of Sant’Apollinare is the two long mosaics down either side of the nave. On one side a procession of female martyrs leads to an adoration of the magi, but this is nothing like the Three Kings we are used to from later ages. They are in extraordinary exotic garments, and by some accounts are actually dressed like contemporary Gothic nobles.

I had thought that this picture of the Three Kings with their fancy tights and their Phrygian caps was unique, but I was wrong, as I discovered on visits to the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore and the Basilica of Santa Sabina in Rome.

On the other side is a procession of male martyrs, leading to an enthroned Christ. Leading the procession is St Martin of Tours, a vociferous opponent of Arianism, to whom the church was rededicated after the suppression of Arianism under Justinian. St Martin’s portrait must therefore have been added as part of the other redecorations, which explains his different costume. Of course we do not know the identity of the saint whose image was destroyed to make way for St Martin.

One can only speculate how glorious the apse decoration behind the altar must have been, given that this was where they usually put the best bits. Apparently though this too was subject to redecoration under Justinian. But in any case the area was later disastrously redecorated in a 17th-Century wedding-cake style, so we will never know.

The Neonian (Orthodox) Baptistery

This is one place we didn’t get to in 2008. There are two ancient baptisteries in Ravenna. One, featured in my earlier article, is the “Arian Baptistery” which was built by Theodoric for the use of his fellow Arians. The other, known as the Neonian (after a bishop Neon) or “Orthodox” Baptistery is about fifty years older, from the end of the 300s or beginning of the 400s. This makes it older even than Galla Placidia’s mausoleum, predating the fall of the Western Empire by seventy years or so.

Inside, in the centre of the dome, is Christ being baptised. The River Jordan is represented as a sort of pagan river-god, and Christ himself is shown as youthful and blond, although bearded, unlike the clean-shaven Christ of the Arian Baptistery.

Around the dome are the twelve apostles, and beneath them are what look like classical buildings, with seats and tables, which in the case of the evangelists are bearing their gospels.

The quality of these depictions of the apostles is extraordinary, better even than the near-contemporary mosaics in the Mausoleum of Santa Costanza in Rome. It is dangerous to generalise about an era from the work of (presumably) a single artist, but based on what has survived, stuff as good as this would not be seen again for many hundreds of years.

The Chapel of Sant’Andrea

Our final visit was to the little chapel of Sant’Andrea, part of a complex of ancient buildings which is now the archiepiscopal museum. There is not as much information available as for the other Ravenna UNESCO sites, but I have found that it dates from the time of Ostrogothic rule in Ravenna. It was not however Arian. As I observed in my earlier post on Ravenna, the Goths were a tolerant lot and were happy to allow the orthodox Catholics to worship unmolested – a tolerance that Justinian’s regime obviously did not reciprocate when he took over again.

Like the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, it is very dark inside, so one has to push the ISO a bit, and do some corrective work in post-processing.

The association with Saint Andrew is due to the fact that the saint’s alleged remains were relocated to Ravenna from Constantinople in the 6th Century. Possession of such remains by a city was both prestigious and lucrative, so people went to a lot of trouble to acquire them, and if that failed, then a convenient miracle often occurred to reveal a substitute set.

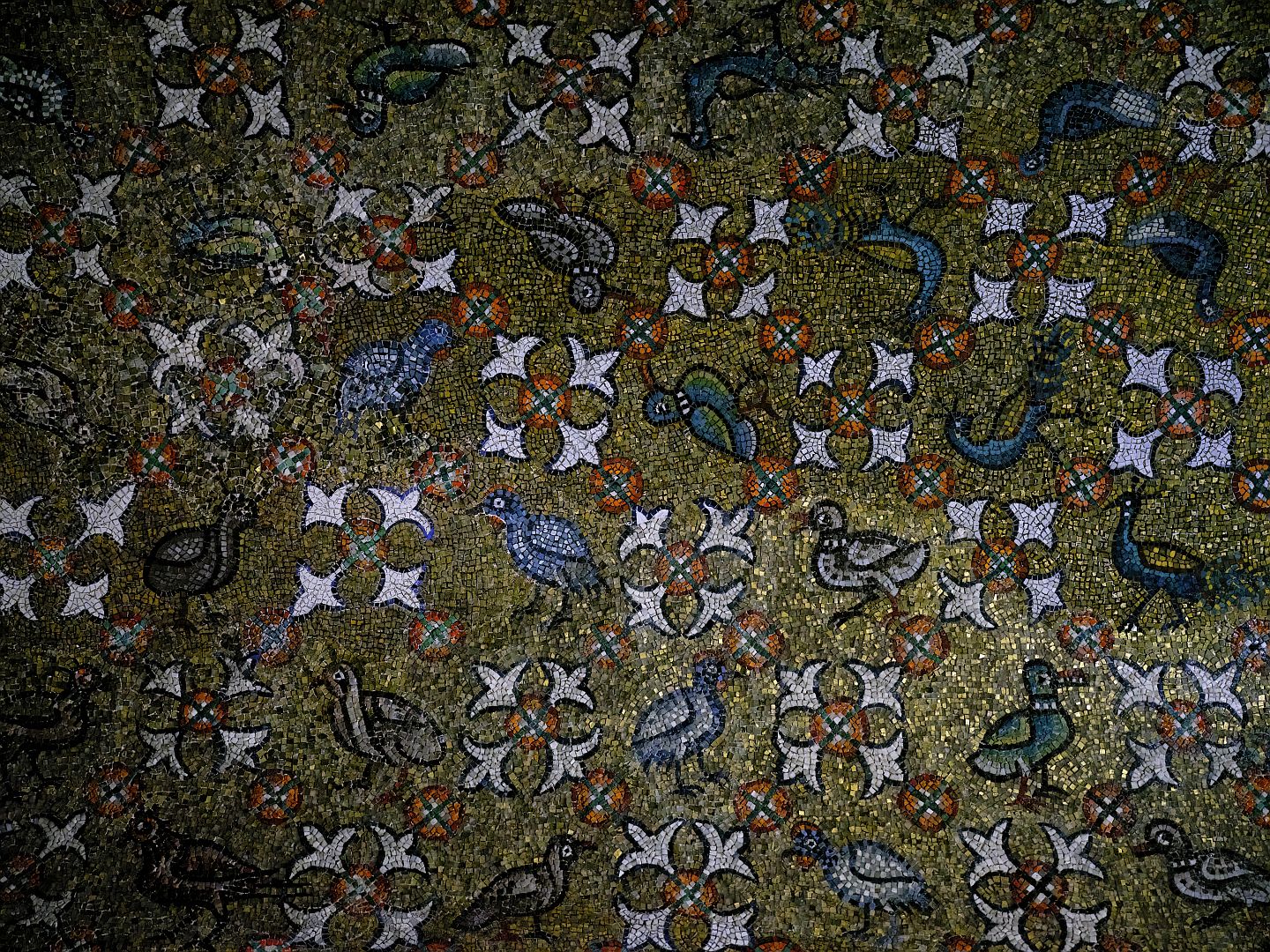

Two things are memorable about this chapel. One is that Christ is represented dressed in late-Roman military costume (indeed at first I assumed the picture was of the Archangel Michael). The other is a ceiling covered in cheerful-looking birds. Birds are a feature of early Christian art, but these ones seem to have more character than most.