Here is a brief photo essay featuring pictures taken on a walk through the inner Rome suburb of Nomentano to the Castel Pretorio, the Aurelian Walls and Porta Pia. The pictures didn’t really lend themselves to a unifying theme, so rather than trying to manufacture one I thought I would let the walk itself be the theme.

In August this year, at the national holiday of Ferragosto, I again stayed in Rome for a few nights on the basis that Rome is one of the few places in Italy where accommodation actually gets a bit cheaper during August; outside the historic centre the city is considerably emptier then. Last year we visited and I wrote about the origins of the holiday and a visit to the Milvian Bridge, site of one of the more momentous battles in history.

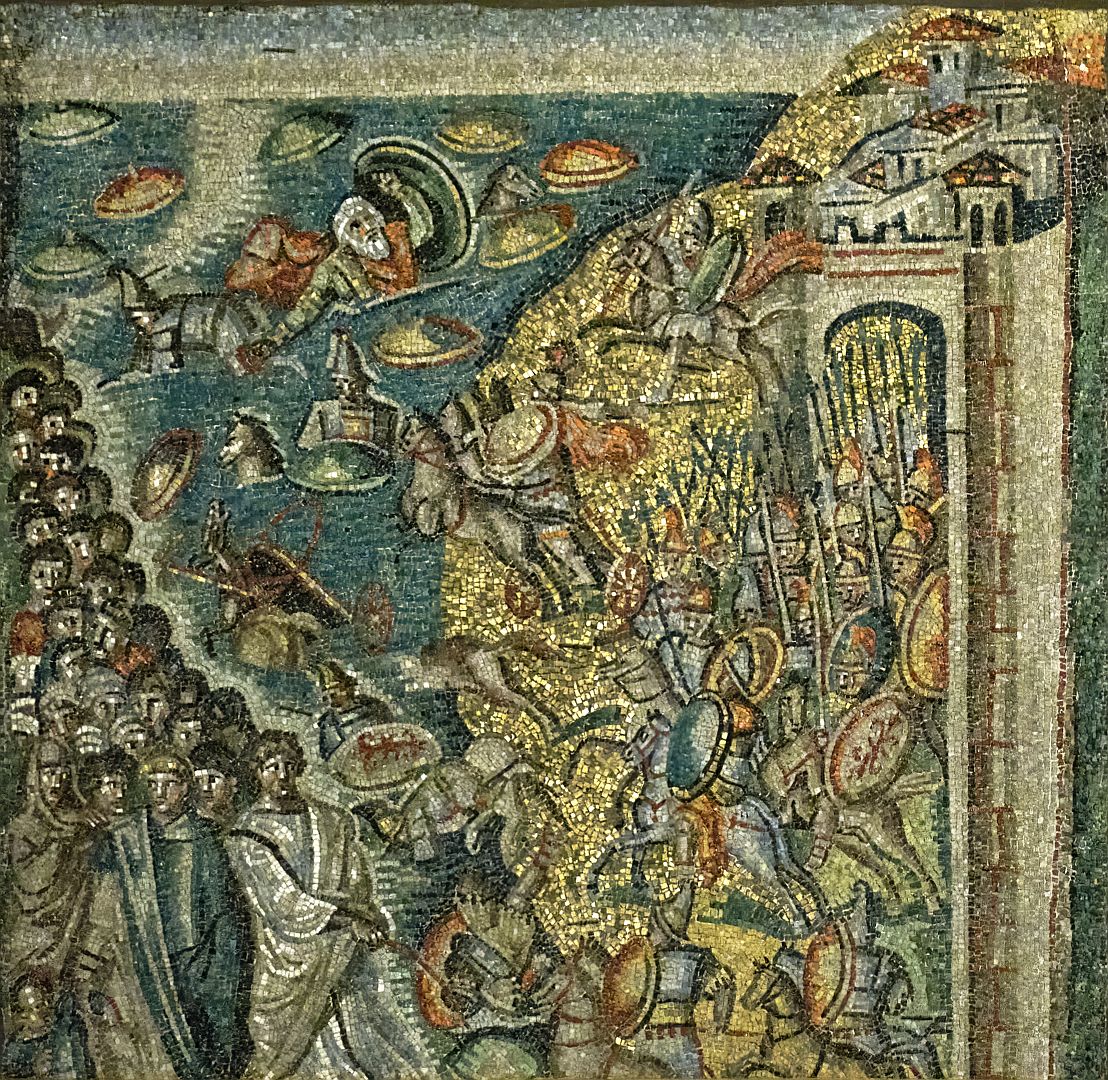

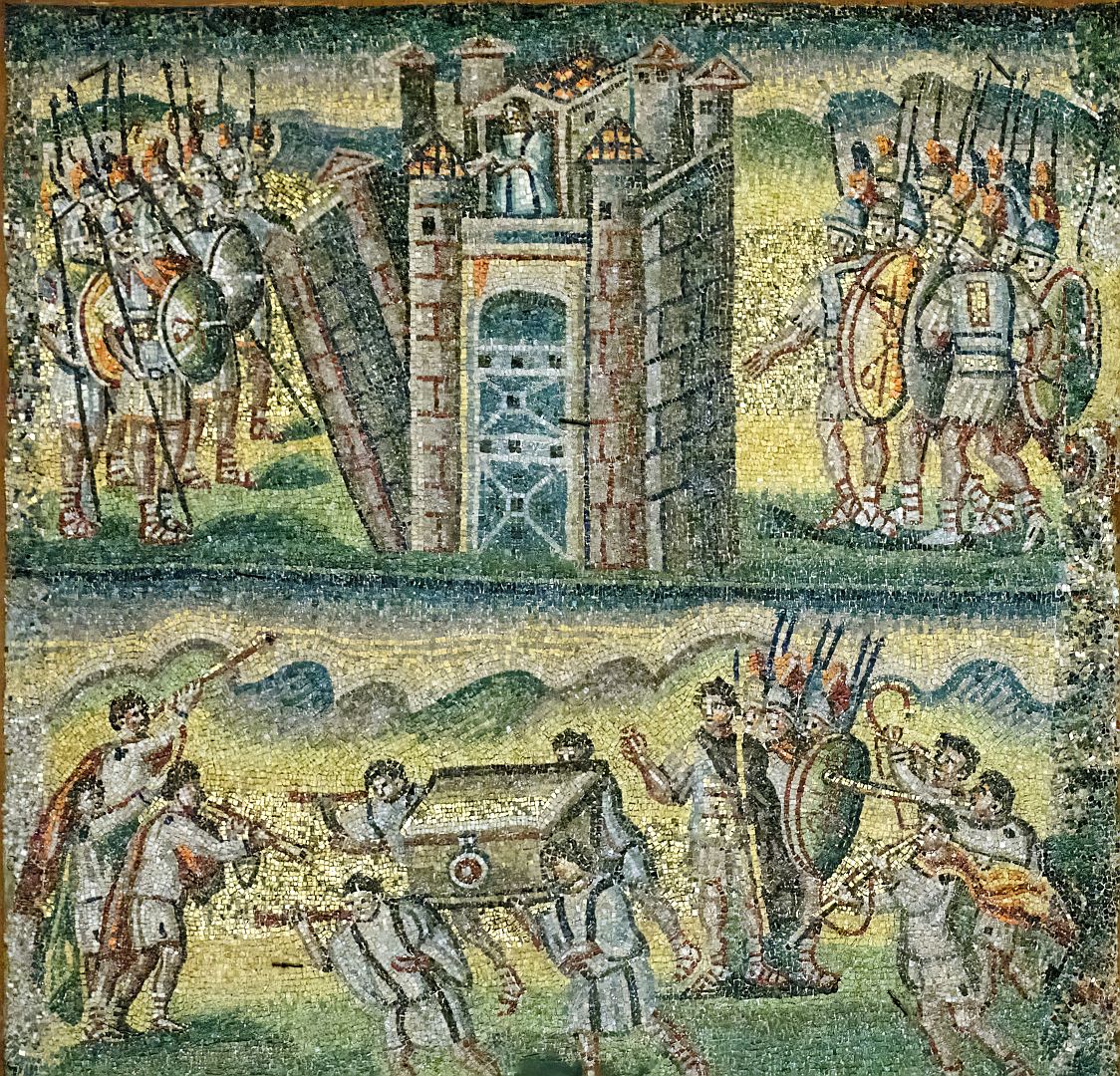

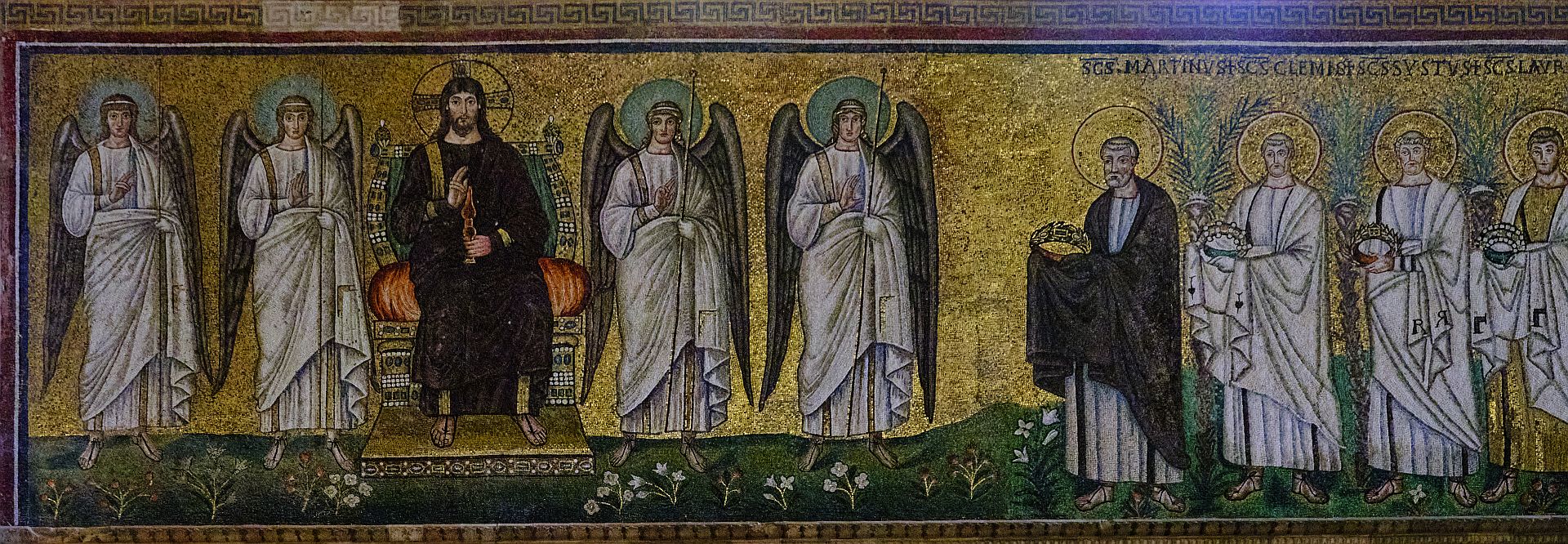

To the extent that I had any objectives other than staying in an air-conditioned hotel room, they were to take more photographs of paleochristian churches for future articles. Since then I have already published one on Santa Maria Maggiore, Santa Pudenziana and Santa Prassede featuring photos previously taken, and some taken on this visit. There will be at least one more to come.

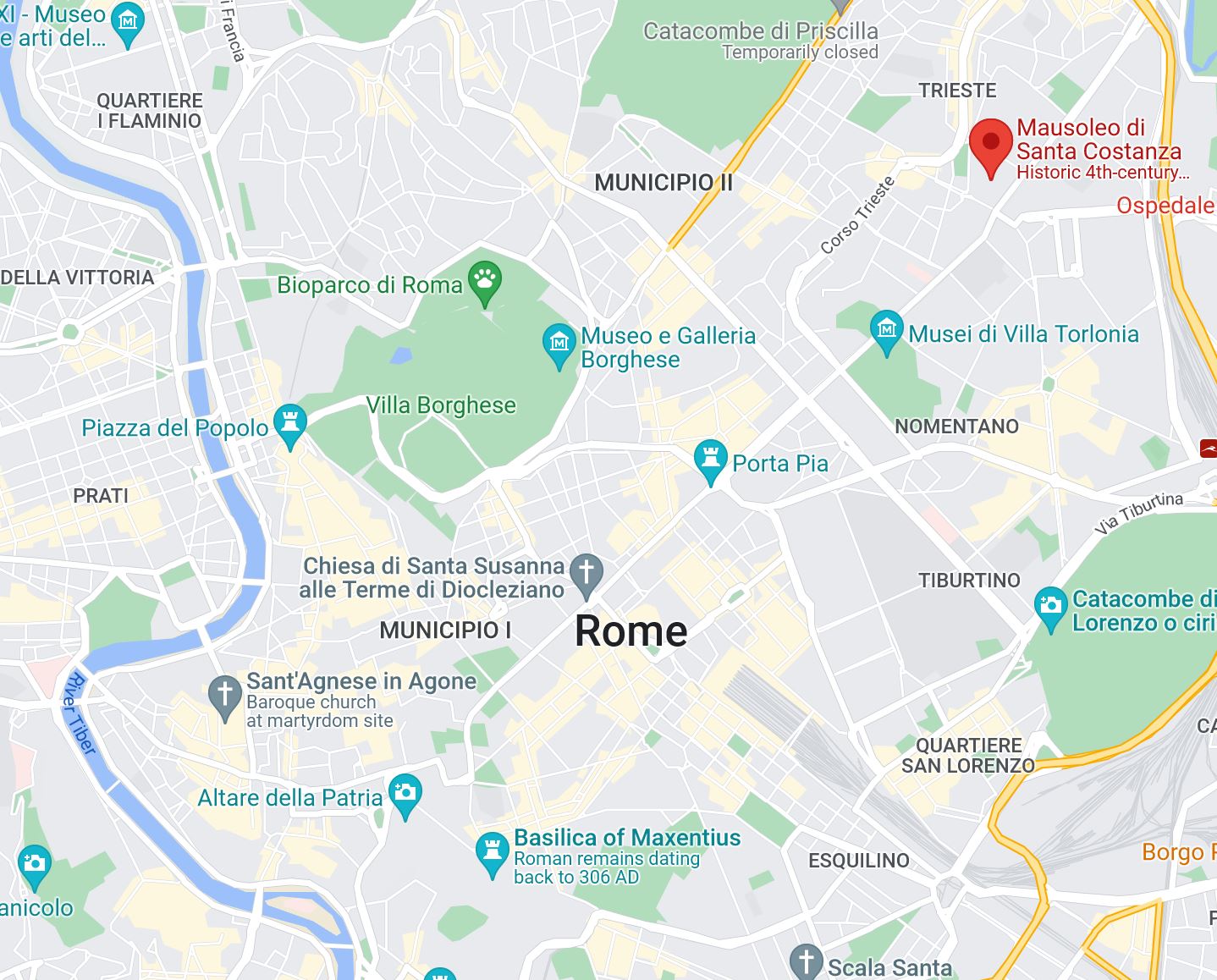

Normally at this time of year the public transport in Rome is comparatively empty, but this year the authorities had decided to take advantage of the season to close one of the two Metro lines for maintenance, so the buses were rather crowded. Given that, one morning I looked at the map and decided that I could probably achieve some of my objectives on foot.

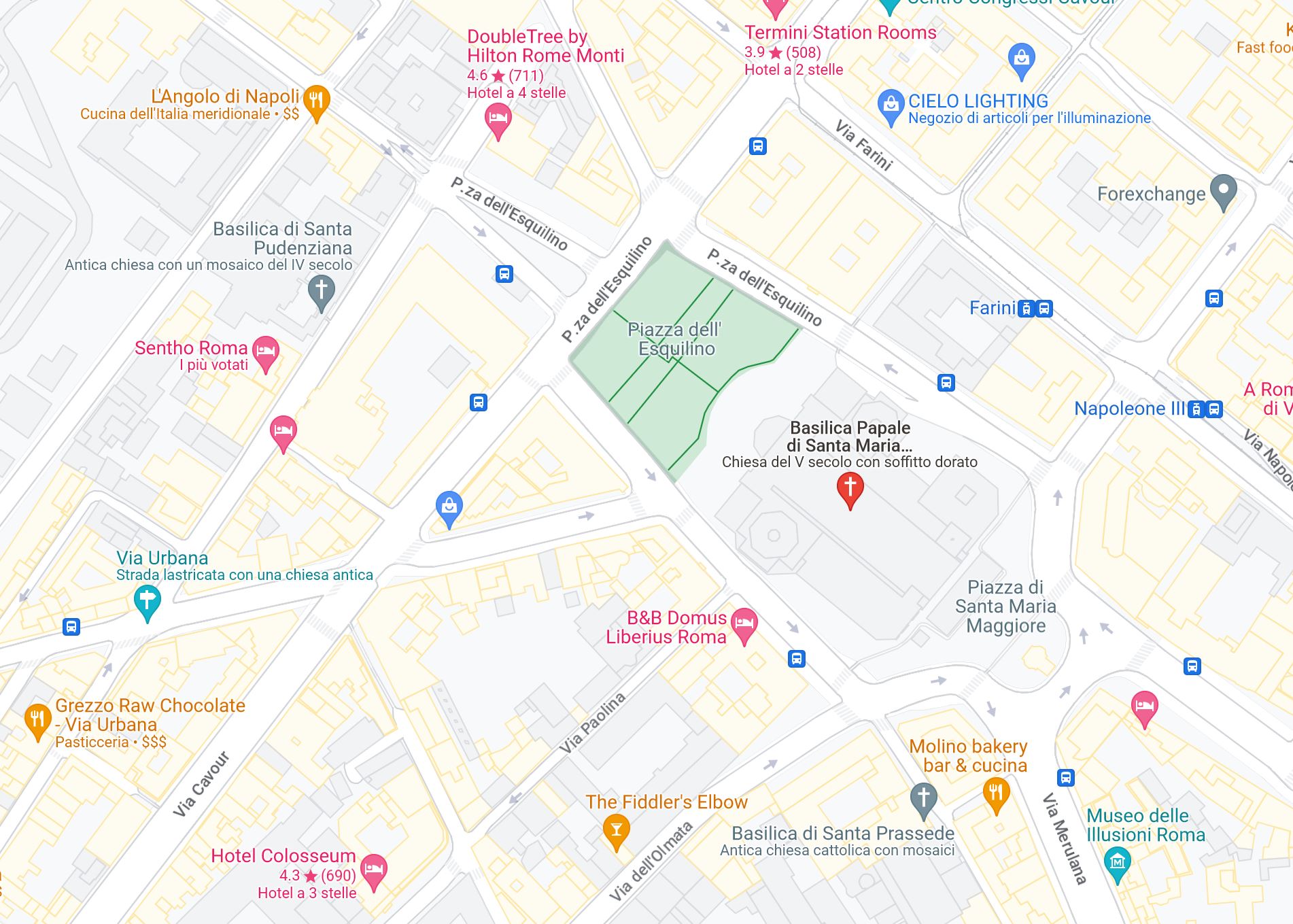

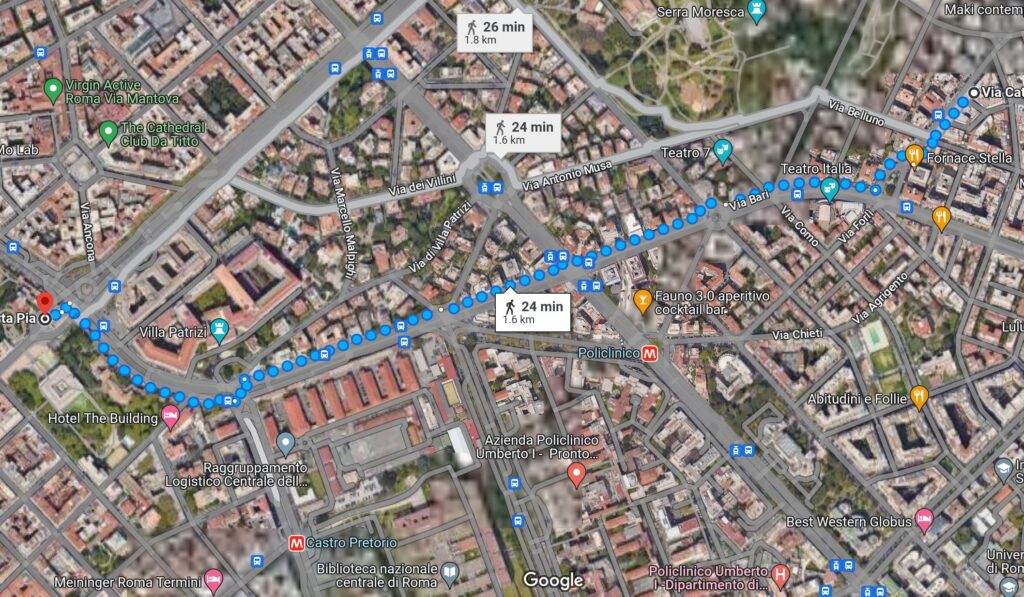

The map below shows the first part of my route. Because I was intending to take architectural photographs, sometimes indoors in low light, I took my heavy Fujifilm GFX 50R medium-format camera with me rather than the little Fujifilm X-Pro3, despite the extra discomfort.

I started at a favourite Sicilian bar in Nomentano, and after coffee and a pastry, set off down Via Catanzaro. One of the advantages of being in Rome during Ferragosto is that one can from time to time step into the street to compose a photograph without being immediately flattened by surging traffic, as would happen at any other time of year.

When I first realised that the word palazzo in Italian can mean “apartment block” as well as palace”, it struck me as a bit odd, but looking at some examples in Rome one realises that it is not entirely inappropriate – the architects were clearly trying for that sort of effect.

The rococo palazzo in the picture below, in Via Morgagni, was very striking; it was apparently built in 1926. The inscription on the front – NON DOMO DOMINUS SED DOMINO DOMUS is a quotation from Cicero, meaning that it is not the house (or family) that confers honour on its head, but the behaviour and bearing of the head that brings honour to the house. I don’t know what the significance of the snails at the top is, but they are a nice touch.

One sees quite a lot of early 20th-Century public artworks in Rome, and the tendency is to mentally label the more monumental examples as “fascist” art, because, well, fascists liked that sort of thing. And since public art is usually paid for by the state, it often appears in contexts associated with the ideology of the government of the day. But it is correlation rather than causation – sculptors in non-Fascist regimes like Jacob Epstein in Britain were producing public works in similar styles.

In Italy, one clue is to look at the dates on public inscriptions. If there is a date, followed by a smaller number with “A” and/or “EF” then they are saying “Year (Anno) X of the Fascist Era (Epoca Fascista)”. Once you know to look, it is actually rather surprising how often you still see this in Italy – there was nothing like the sort of comprehensive removal of reminders of Nazism that happened in Germany after the war.

Another clue is classical references in the architecture. Identification of the modern Fascist state with imperial Rome, right down to putting “SPQR” on the manhole covers, was ubiquitous.

Below is a building from 1925, the Dopolavoro of the Italian railway workers in Rome, on Via Bari.

What was a dopolavoro? Literally meaning “after work”, the dopolavori were social clubs for industrial and agricultural working people, and as elsewhere in Europe had their origins in the late 19th Century. Some were created by trade unions, and many by so-called “mutual assistance societies”. With the advent of Fascism, the trade unions were banned and the independent societies were incorporated into state-controlled organisations. The dopolavori proliferated, though, because the Fascist government liked the idea of them. The movement continued after the war and these days if you go to the website of the Dopolavoro Ferroviario (DLF) you will find an organisation offering cultural opportunities and cut-price travel.

Continuing along Via Catania I saw to my left the wall of a large building of obvious ancient Roman construction. This was the Castra Praetoria, or in modern Italian, Castel Pretorio – a name familiar to me from the metro station of the same name, but actually the remains of the barracks of the famous Praetorian Guard.

In Republican Rome, the title praetor was given to men serving as magistrates, or as commanders in the army. It is from the bodyguards of the latter that the Praetorian Guard was descended. In imperial times they were the elite corps of the army that protected the emperor, fought beside him in battle, and sometimes performed sensitive intelligence missions.

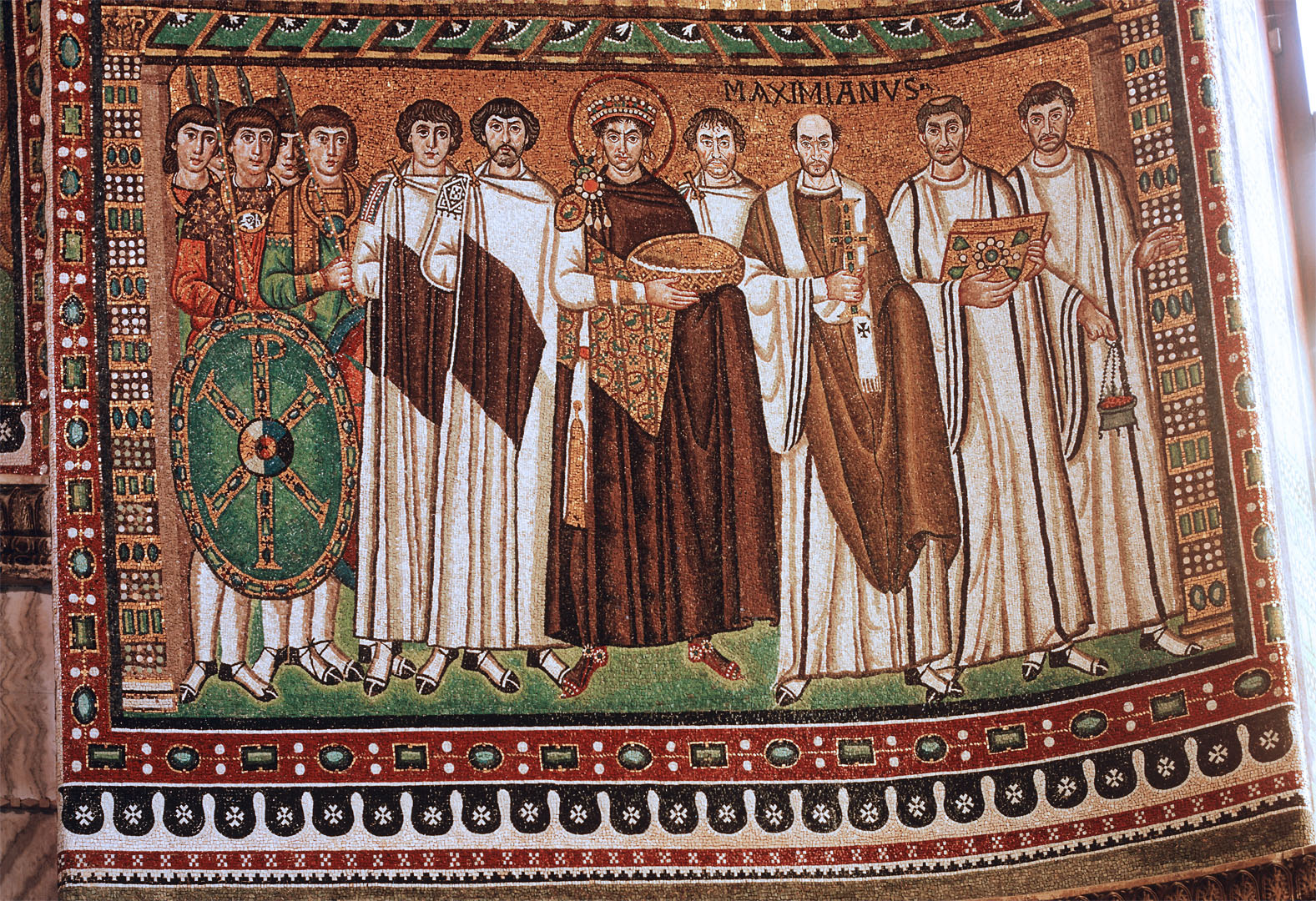

Over time they went from protecting the emperor to sometimes choosing him as well, starting with the famous occasion where they supposedly found Claudius hiding behind a curtain after the assassination of Caligula. They were the only troops permitted to carry weapons in Rome without special authority, and being known for their arrogant behaviour they were not popular in the city. Emperors needed to keep the Praetorians happy with generous bribes to retain their loyalty, but one of the occasions when they were completely faithful to their duty was their final act, when they fought alongside the emperor Maxentius on the losing side against Constantine at the battle of the Milvian Bridge. This was not, as later propaganda had it, the final triumph of Christianity over pagan persecution, because Maxentius had already promulgated an edict of toleration for Christianity (for which Constantine then took the credit). But it was the victory of one political faction over another, and Constantine took his revenge by disbanding the Praetorians and demolishing their headquarters.

Constantine didn’t demolish the Castel Pretorio completely, as it formed part of the Aurelian Walls of Rome, and I continued along Via Catania with those walls now to my left. The Aurelian Walls were built around 275 AD, after a long period of peace in which Romans did not feel threatened, and the city had spread far outside the original city walls of six centuries earlier. But the Vandal incursions into Italy of the 3rd Century put an end to that complacency, and the Emperor Aurelian hastily commissioned the walls which bear his name.

In 275 the walls were probably not strong enough to withstand a determined siege. That wasn’t their original purpose, though – it was to deter hit-and-run raids by barbarians, and to allow troops to be deployed rapidly to the site of an attack from one of the many watchtowers. However a few decades later Maxentius raised the height of the walls to make them a serious defence against siege warfare. It is an interesting hypothetical to consider what might have happened if Maxentius had decided to retreat behind the walls instead of engaging Constantine’s army at the Milvian Bridge.

Around 1,800 years later, the walls are still in pretty good condition where they have not been demolished to let roads through. I suspect that there are three reasons for this. Obviously, the first is that the walls were built strongly to start with – brick outer layers may not seem all that resilient but when the space between is filled with concrete and rock the result is very tough. The second is that brick and concrete are not materials that lend themselves to be scavenged for re-use, as happened to so much stone, marble and bronze from ancient buildings.

But probably the most important reason is that on a regular basis the walls continued to be needed for defence, right up until the 1870s, so the city authorities would have tried to keep them well-maintained. Which brings me – both in the narrative and in terms of my actual location – to Porta Pia.

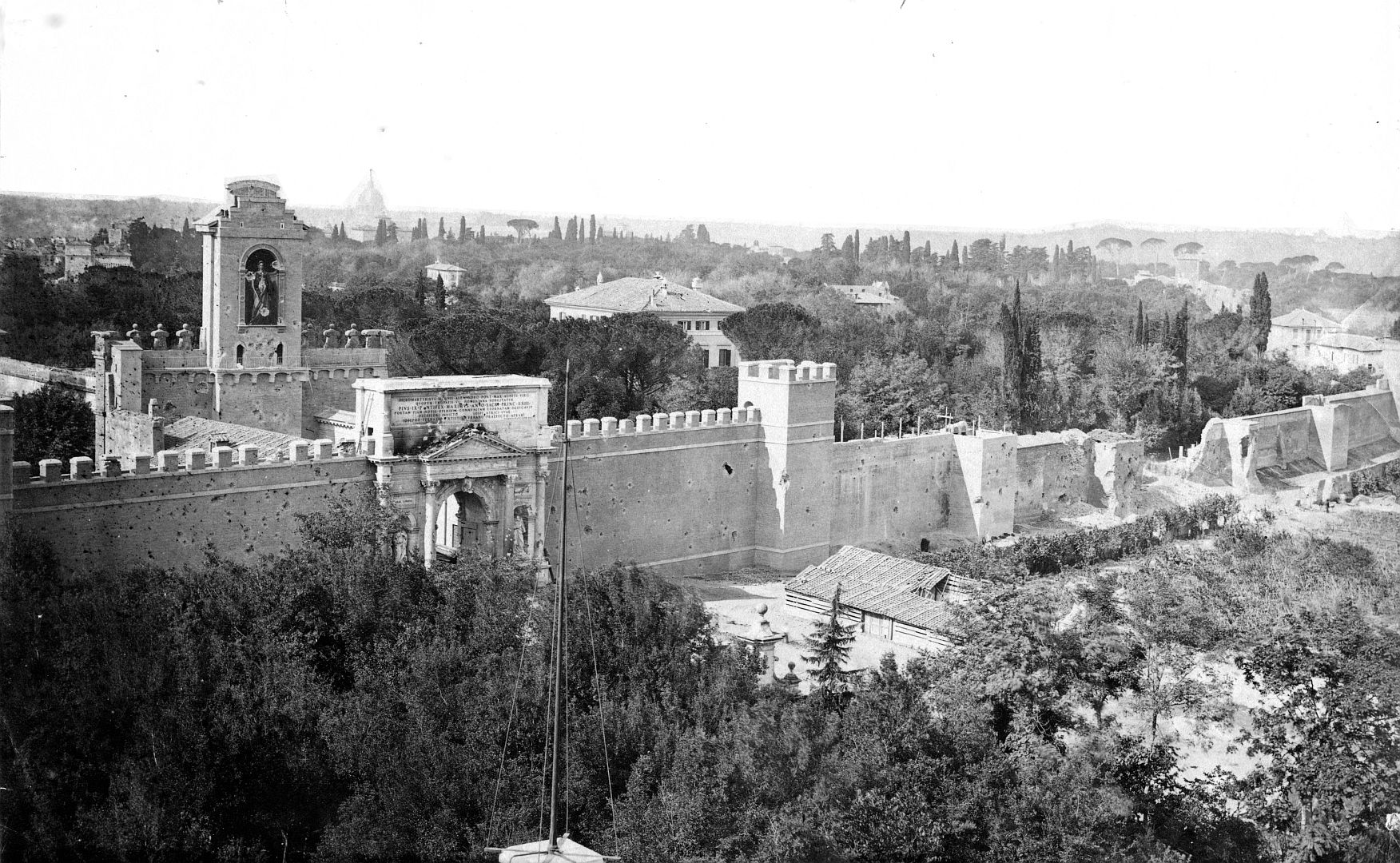

The city gate of Porta Pia, replacing an older gate which was too small, was erected in the 1560s in the reign of Pope Pius IV, from whom it took its name. It was designed by Michelangelo who offered three versions, but Pius did not want to spend a lot of money and chose the cheapest-looking of the three. Even then the external façade was not completed until the 1860s, on a neo-classical design which is supposedly faithful to Michelangelo’s intentions (we do not know because the original drawings have been lost). But the facade on the inside of the walls is authentic Michelangelo.

That’s all very well, but it isn’t the reason why every Italian schoolchild learns about the Porta Pia in history lessons. No, in 1870, the Porta Pia was where the army of the Kingdom of Italy forced its way into Rome. If you are not familiar with the history of the Risorgimento, that might have come as a bit of a surprise – the Italian army, capturing Rome?

When Italy united in 1861, the new Italian parliament, meeting in Turin, declared that Rome was to be the capital. But there was a problem: the Pope was Pius IX, of whom much had been expected by progressives on his accession as a comparatively young man. But he had grown increasingly reactionary as he grew older. He refused to recognise the Kingdom of Italy, denounced it as an abomination and told Italians that it was a serious sin to vote in national elections. He then spent the rest of his life sulking. Papal forces were quickly evicted from almost all the Papal States, but the Italian Army stopped at the walls of Rome. There were a couple of reasons for this. One was that it would not have been a good look to shed Italian blood in a conflict with the forces of the Catholic Church, a prospect which seriously troubled King Victor Emmanuel. But the main reason was that Rome was strongly garrisoned by mercenaries and foreign forces, most of which were provided by the French Emperor Napoleon III.

Over the decade or so following the establishment of the Italian state, various attempts were made to find a negotiated solution, but they almost always ended with Pius throwing a tantrum, leading to the point where, in 1870 and to the general surprise of theologians, he declared himself infallible. Papal infallibility only applied to doctrinal pronouncements, but on the other hand Pius obviously considered the legitimacy of the Italian state a matter of doctrine.

Everything changed with France’s impending defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, which saw the hurried withdrawal of French troops from Rome. Faced with the impossibility of defending the city, Pius still refused any kind of agreement, but privately let it be known that if the Italian forces were able to breach the city’s defences he would yield to force majeure. And those defences were, mostly, the Aurelian Walls.

In the event, the loss of life – although completely unnecessary – was not huge. On the 20th of September 1870, after a pounding by artillery, a breach was opened just to the west of the Porta Pia, the Bersaglieri light infantry of the Italian army entered Rome, and after brief fighting, the Papal forces laid down their arms. Most, being foreign mercenaries, were repatriated, although the Swiss were allowed to remain in Papal service. At a subsequent plebiscite, the vote by Romans to become part of Italy was overwhelmingly in the majority, so while 19th-Century plebiscites did not observe modern standards of integrity and transparency, it was probably a fair representation of public opinion.

But this was an armistice, not a formal peace. While the Pope and his administration were given the territory of the Vatican and certain other church properties, and afforded extravagant diplomatic courtesies by the Italian Government, they still did not formally recognise the Italian state, or concede the loss of their former territories in central Italy. Pius declared a mass excommunication of all the Italian forces involved in the military action.

In fact, the problem was not solved until 1929, when the new Italian Prime Minister Mussolini negotiated the “Lateran Treaty”. Meanwhile, many Italian towns renamed their principal streets and piazzas “XX Settembre” in commemoration of the capture of Rome.

Just outside the gate is a monument to the Bersaglieri – and we can actually call this one “fascist” because it was commissioned by Mussolini (whose brief military service in the First World War was in the Bersaglieri). Although the soldier on top is in a uniform from the First World War, he is charging straight at the gate. In case you missed the point, the gatehouse of Porta Pia itself now houses a museum of the Bersaglieri, and once inside the gate, the name of the street changes from Via Nomentana to Via XX Settembre.

After the capture of Rome, the Bersaglieri were immediately celebrated as heroes, and, with the Alpini, they remain a much-loved symbol of the Italian Army. I’m not sure what the best translation of the name would be – perhaps “riflemen”, “marksmen” or more generically, “light infantry”. I read somewhere that Piedmont lacked the resources to maintain a standing force of light cavalry, so the requirement for a highly-mobile battlefield force was filled by the Bersaglieri, which is why, rather than marching, they do everything at a run. And very fine they look too with their ostrich-plumed hats.

From Porta Pia I continued south towards the Esquiline Hill, then to the Colosseum, past the Palatine Hill and the Circus Maximus, then up the Aventine Hill, ending at the Basilica of Santa Sabina and the Giardini degli Aranci, from which there are excellent views over the Tiber towards Trastevere and the Vatican. That will be the subject of a separate post. Edit: here is that post.