During the holiday week of Ferragosto, we visited a semi-deserted Rome to see the Milvian Bridge, site of a crucial battle in 312 AD.

In August, accommodation in many parts of Italy changes from having been comparatively inexpensive to being breathtakingly expensive. And that is because in August there falls the holiday of Ferragosto, where everything closes down and everyone heads out of town.

Ferragosto has its origin in something in Ancient Rome called Feriae Augusti – the holiday of Augustus. When Octavius Caesar took over as emperor he renamed himself Augustus. He also renamed the month of Quintilis in the newly-reformed calendar after his predecessor Julius Caesar, so it became July, and he renamed the month of Sextilis after himself, so it became August. And because the hottest weather was in August and no-one felt like working, according to the popularly accepted story he decided to give all the working people of Rome a few days off, and gave himself the credit. It would have been marked by chariot races, and various religious festivals to honour harvest deities and the like. Needless to say there is debate about how accurate this account really is.

These days the 15th of August is Ferragosto and for a week or two on either side, factories close, public administration grinds to a halt and four out of five shops have signs in their windows saying chiuso per ferie (closed for holidays). Vast numbers of Italians head away, mostly to the coast but also to the mountains, and often to exactly the same place they have been going all their lives. It may be an urban myth, but there have even been stories of wanted criminals being captured in August because the police staked out the places they had been going to for holidays since they were children.

It would have been truly remarkable if the modern Ferragosto was an uninterrupted survival from antiquity – and it isn’t, of course. Or not much. What actually happened is that at first, like all other pre-Christian holidays, Feriae Augusti was incorporated into the Christian calendar, in this case being allocated to the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin. No doubt under the new administration the festival retained some of the characteristics of the original, if for no other reason than that it was hot, no-one felt like working, and in any case the harvest was in.

Then, in the 1930s, the Fascist government decided to revive Feriae Augusti as a secular holiday. Like authoritarian social movements elsewhere they liked the idea of organised leisure for factory and farm workers, and thus many working class people experienced trips to mountains and the seaside for the first time. The Fascists were also enthusiastic about any links, actual or imagined, with ancient Rome, so the Feast of the Assumption got turned back into Feriae Augusti, or Ferragosto in modern Italian. Of course the religious festival is still observed, so it wasn’t an actual reversion to paganism.

After the war, the Italians had got rid of the Fascists but they found they liked the idea of shutting the whole country down for a holiday, so they kept it. And every year the cities empty, the roads clog and the beaches fill up with thousands of identical beach umbrellas, precisely arranged, where people can come back to the same position, next to the same people, every year. Most decent beaches in Italy are private property and are run as businesses, handed down through generations of the same families.

It slowly dawned on us that Rome was one of the few places in Italy where accommodation might actually get cheaper during August. And thus it proved.

We had read about how Rome is deserted during Ferragosto. Not the historic centre, because that is still full of foreign tourists, but everywhere else. We took that to be a bit implausible – after all, who could imagine Rome not being busy? But it really isn’t. The traffic was light on the Ring Road, and as we arrived in the inner northern area of Nomentano there was almost no-one on the roads. The photo below was taken from the middle of a road, the crossing of which would have been suicidal when we were last there in June.

All our favourite restaurants were closed, of course, but the hotel directed us to one which was open and which proved to be a decent little Roman trattoria. And a Sicilian cafe on the corner was open for breakfast pastries and evening aperitivi, so the necessities of life were available.

A visit to Central Rome was a bit of a contrast. While the back streets might be quiet, in the Trevi Fountain – Pantheon – Piazza Navona triangle there was a full load of tourists surging back and forth like the tides. And because this was the time of the northern hemisphere summer holidays, a high proportion of the crowd was made up of junior bogans of all nations. And they were making full use of the greatest menace in Rome this year – electric bikes and scooters. The scooter riders were the worst. They tore along both the streets and the pavements at stupid speeds, and when they had got where they were going they abandoned the blasted things wherever they felt like it.

None of them were wearing protection for heads, elbows or knees, so I wonder how busy Rome’s hospital casualty departments are this summer. Italian local governments don’t have much patience for this sort of thing so I hope to read before long that e-scooters and e-bikes are being better regulated, and stupid behaviour thereon is attracting fines. After all, you can get fined for sitting on the Spanish Steps.

The photo below shows the Porta del Popolo, with a statue of St Peter vainly pointing out the part of the city by-laws dealing with electric scooters.

The next day we decided to take advantage of the lack of crowds to do our own tour of Rome on public transport. The hop-on-hop-off Rome tourist buses cost €15-20 or more, but we paid €7 each for a 24 hour ticket and had many more options than the tourist bus. We started by taking the number 61 bus which took us around the old Aurelian Walls of Rome for a bit, then entered the central city through the Porta Pia, the gate where Italian troops forced entry to Rome to defeat Papal forces in one of the later episodes of Italian unification in 1870. The bus then bounced along some rather potholed downtown streets before taking us through the Borghese Gardens and depositing us in the “Viale Giorgio Washington” just outside the Porta del Popolo.

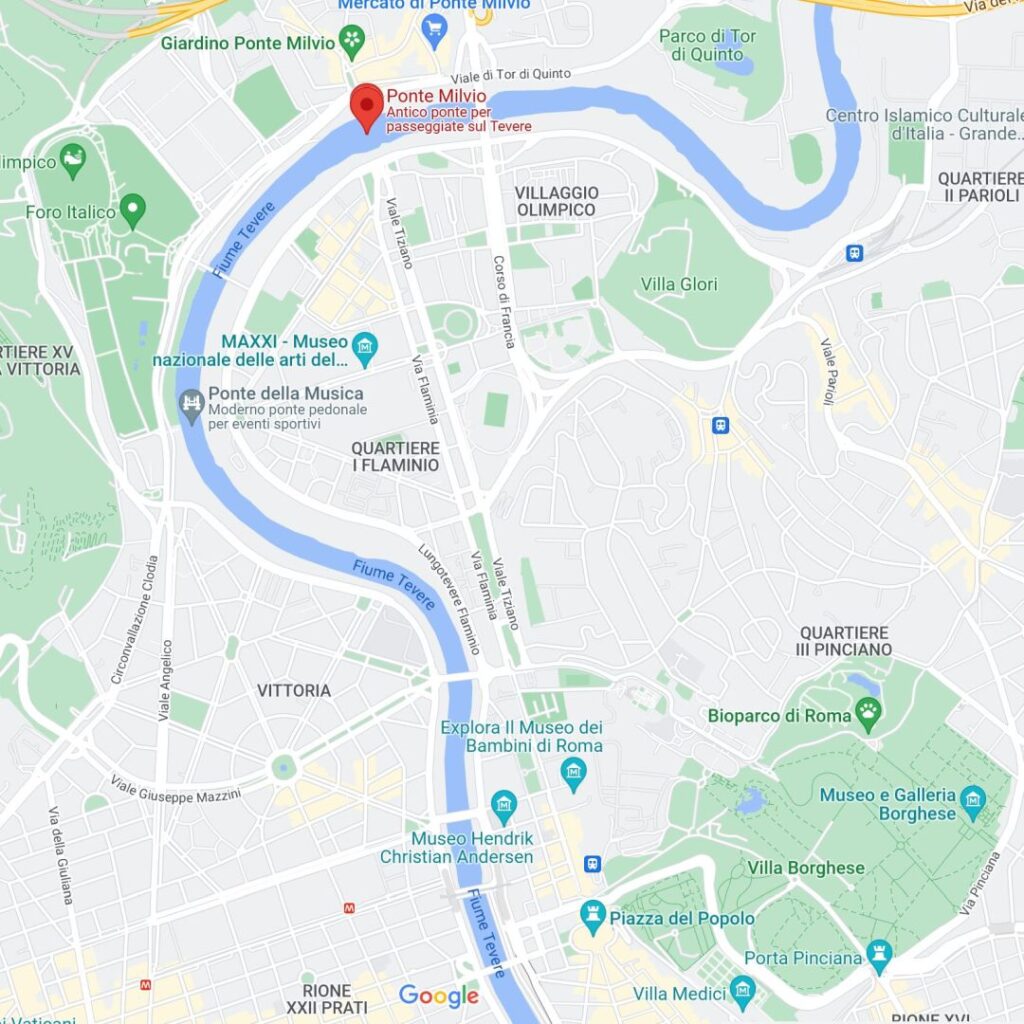

That is where the old Roman military road, the Via Flaminia, left the city on its way north. Its dead straight path out of Rome is followed by the modern road, which still bears its name. The number 2 tram goes along it, so we jumped on board.

The tram took us past some grandiose buildings housing government ministries, and some seedy low-cost housing. Out here the Ferragosto effect was very much in force and pretty much every shop and bar was closed and shuttered. A bit like Canberra in the first week of January.

But the main reason we had gone there was because I wanted to see the bridge where the Via Flaminia crosses the Tiber. It is called the “Milvian Bridge”, or the Ponte Milvio in modern Italian. It is much repaired and remodelled since antiquity, and no longer carries vehicular traffic. Some time in the Middle Ages it was partially destroyed by one of the leading Roman families, to force traffic to use the Ponte Sant’Angelo which was in territory they controlled. Nonetheless some of the stonework around the arches looks as if it might be original.

The old bridge has seen a lot. This was where the legions marched away to conquer Europe, or rebel troops like those of Julius Caesar entered Rome in defiance of the Senate.

As a defensible entry point to Rome it was the site of military actions over the centuries, and the most famous battle was in 312 AD between two rival emperors, Constantine and Maxentius. Constantine won and later claimed to have been inspired by a vision of the Christian cross. He then revoked the remaining restrictions on Christianity and started it on its way to becoming the established religion. As a result the “Battle of the Milvian Bridge” is much celebrated in religious art. Some paintings show Maxentius’s troops seeing the vision of the cross as well, throwing down their weapons and running away. Which is a bit unfair on them.

According to some accounts I have read, Maxentius had actually demolished part of the stone bridge and replaced it with a wooden pontoon bridge, which collapsed when he tried to bring his army back across it. You can see a discussion of the battle in a YouTube video here.

Since his defeat, Maxentius’s reputation was systematically dismantled with a Soviet-style rewriting of history. Some modern historians are trying to rescue his reputation, pointing out that the edict of toleration for Christianity, long attributed to Constantine, was very likely issued by Maxentius. You can see a very interesting discussion of this subject in a YouTube video here.

In addition, Constantine’s personal commitment to Christianity is debated. It may well just have been political pragmatism on his part, since Christianity was well on its way to becoming the dominant religion anyway, at least in terms of the number of adherents. At a time when his legitimacy might have been in question, getting a substantial part of the population on his side would have been a smart move.

There is no doubt though that his mother and daughters were enthusiastic Christians – his mother, the Empress Helena (Saint Helena to the church) paid a visit to the Holy Land and, without any obvious evidence, pronounced that manky old bit of wood to be the True Cross, and that scrubby old hill to be the site of Golgotha, here the Last Supper, there the Holy Sepulchre, and so forth. Most of her topological identifications are still observed by tradition, so she was pretty influential too. One of Constantine’s daughters was Costanza, and one can still visit her beautiful mausoleum in the Via Nomentana. I shall include that in a separate post on Paleochristian sites in Rome.

Edit: I have now posted that article and you can find it here.

The other thing that Constantine did was to move the imperial capital away from Rome to Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople, after himself.

Looking down from the bridge at the Tiber now it seems hard to imagine two armies engaging on the steep banks, but those are artificial, the river having been embanked some time in the 19th Century.

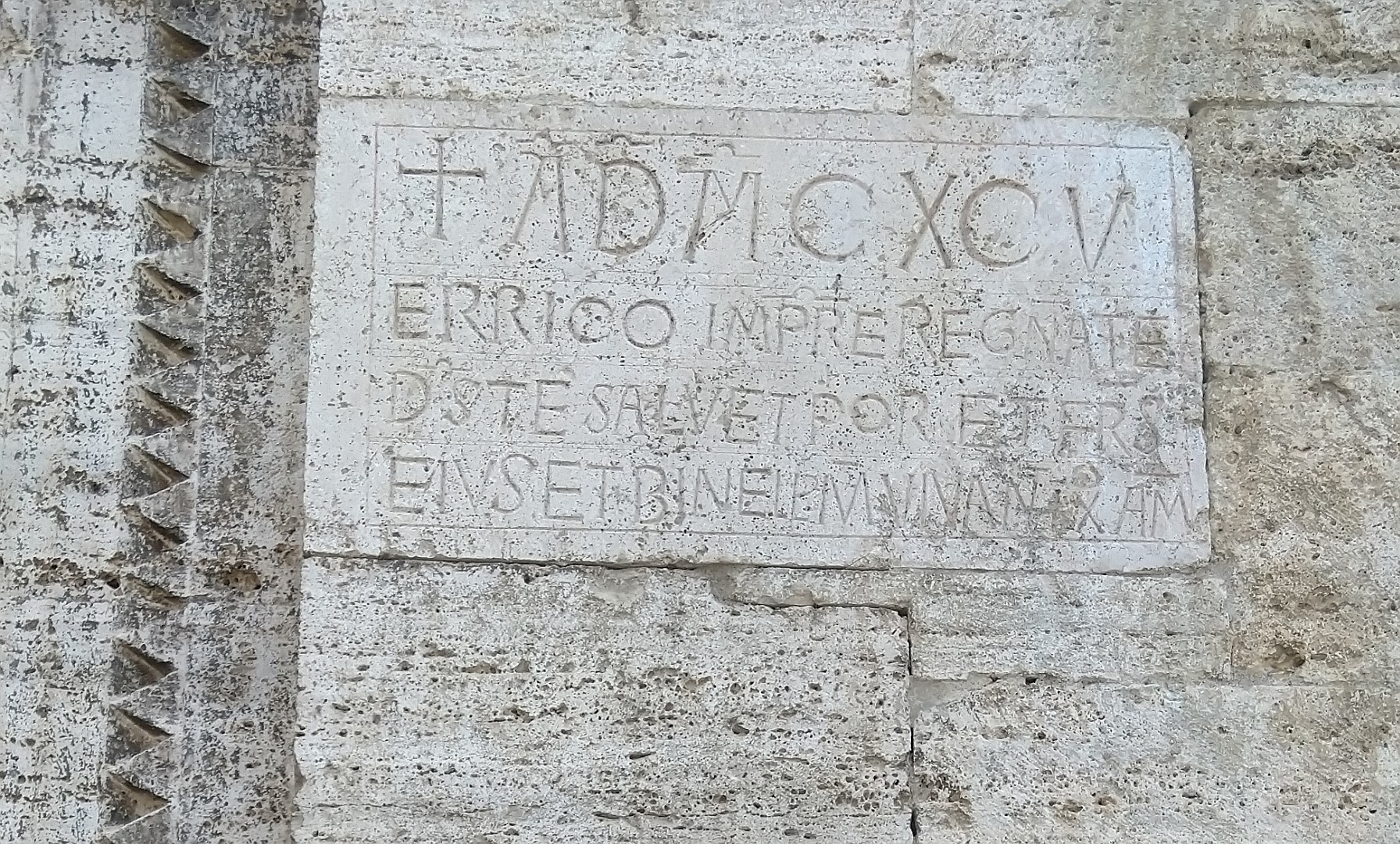

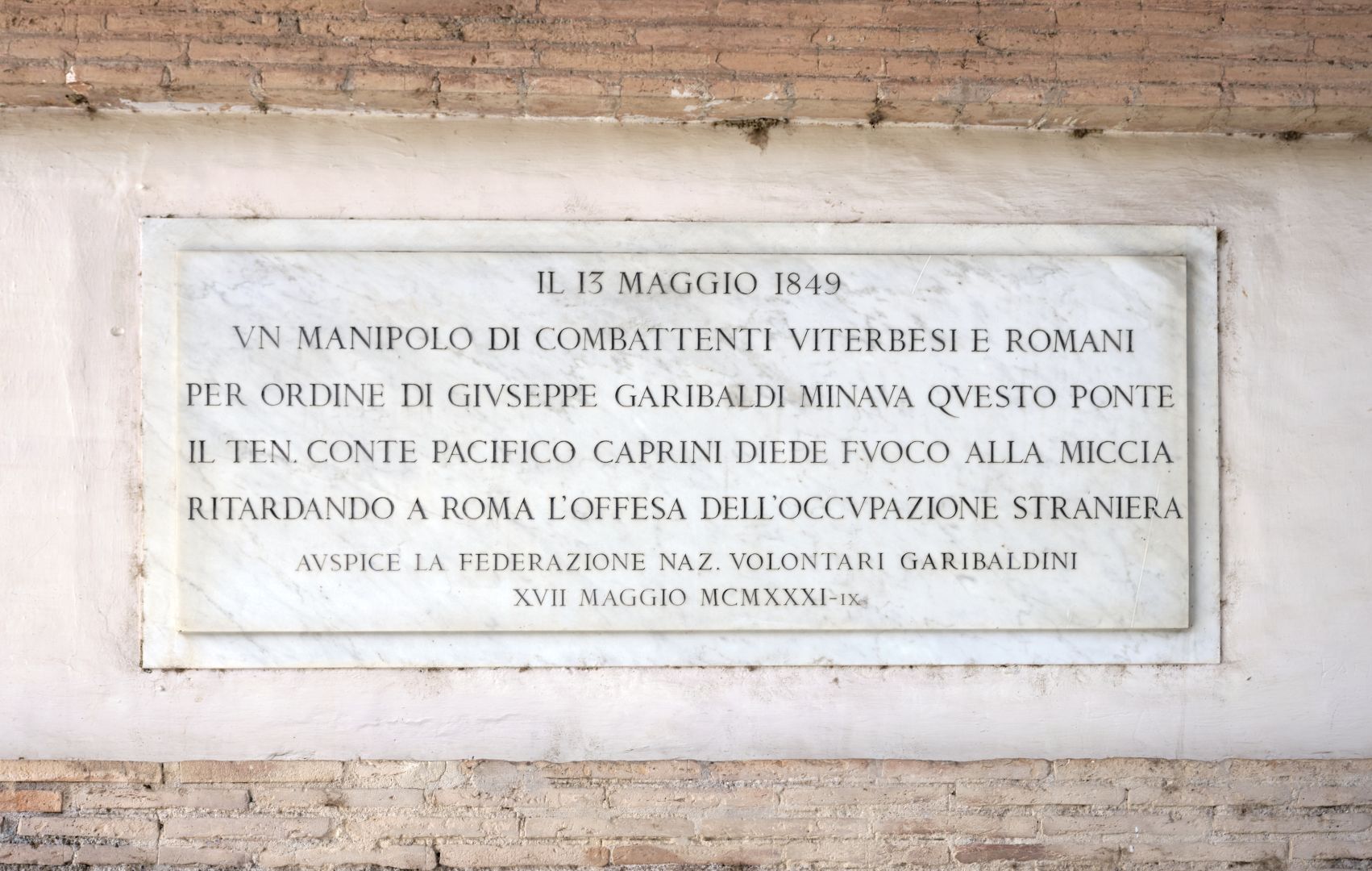

Another military engagement is commemorated on a plaque at the northern end of the bridge. In 1849, when France and Austria came to the aid of the Papacy to snuff out the self-proclaimed and short-lived Roman Republic, a party of Garibaldi’s troops sabotaged the bridge to prevent enemy troops crossing the river.

Once we had caught the tram back we passed through the gate into Piazza del Popolo and suddenly we were back into a Rome that was heaving with tourists. There are a couple of ritzy cafes beside the Piazza – the sort of places where the waiters wear uniforms and you pay more for a glass of prosecco than you would pay for the whole bottle in a supermarket. I was reminded of the travel writer H.V. Morton’s observation that at Florian’s Cafe in St Mark’s Square in Venice, the waiter serves your coffee “with the air of some grandee doing it for a wager”. This place had the same sort of feeling.

Despite the prices it was nice to sit looking out on the Piazza del Popolo with a drink and a sandwich. We were watching a couple of immigrants trying to sell roses to female tourists. They weren’t getting many takers. Then a sudden storm broke and for a moment all was confusion as the tourists rushed for shelter. Although we had only been distracted for a moment, by some conjuring trick the immigrants’ roses had magically been replaced by umbrellas.