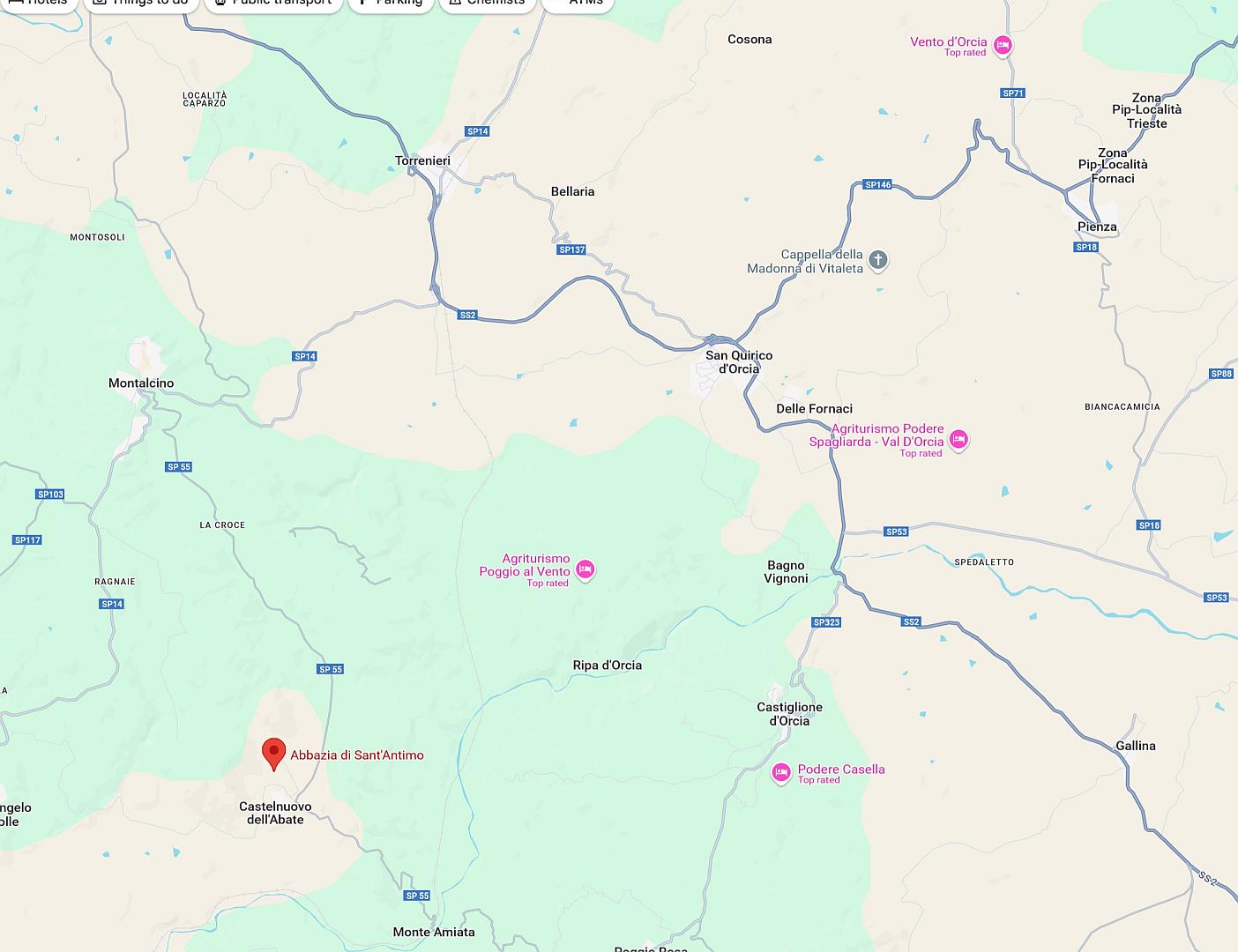

The Abbey of Sant’Antimo is a nine-hundred-year-old Romanesque jewel, and a jewel, moreover, in a setting of great beauty. That setting is a remote Tuscan valley, about ten kilometres south of Montalcino, below the little town of Castelnuovo dell’Abate. We first visited in 1999, and have been back several times since – if we are bringing friends to visit Pienza and the Val d’Orcia, we usually make the trip here via Montalcino.

There seems to have been some sort of monastic foundation here from the 800s, perhaps built over the remains of an ancient Roman villa or temple, but the current building mostly dates from the 1100s.

Which Saint?

The first question is – to whom is this abbey dedicated? Conventionally, most sources I have found say that it is St Anthimus of Rome. He was a 3rd or 4th-Century martyr of whom little is known, and that mostly legend. Not an obvious dedicatee.

Interestingly, there is another candidate, mentioned in the Italian-language Wikipedia article, but not the English one. He is Anthimus the Deacon of Arezzo, also martyred in the 4th Century. Arezzo is not terribly far from the Val d’Orcia, and it appears that there was a story that his martyrdom took place somewhere near the abbey’s location, and a small oratory was erected over his remains.

So on the face of it, it would seem much more likely that the abbey is dedicated to the local boy, Anthimus the Deacon from Arezzo. There is only one problem with this: Anthimus the Deacon was an Arian, an adherent of the sect which rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. Arianism was condemned as heretical by the Catholic church, which would therefore not have considered this Anthimus eligible for sainthood.

I do have a theory: the memory of Anthimus the Deacon is quite likely to have been kept alive in local tradition. The early Middle Ages were not conspicuous for keeping methodical historical records, and it is plausible enough that such a local tradition of a “Saint” Anthimus was conflated with the official saint, thus keeping the locals happy while avoiding the awkward problem of commemorating someone unacceptable. We have seen similar possible examples of hybrid hagiographies in my posts on Santa Costanza and Sant’Agnese and Santa Sabina.

What about Charlemagne?

There is another legend about the foundation of the Abbey in the 800s. In the year 800 Charles, King of the Franks, called “Charles the Great” (Charlemagne in French, or Carlo Magno in Italian), travelled to Rome after defeating the Lombards in northern Italy. There Pope Leo III – to Charles’s surprise, by some accounts – crowned him as Holy Roman Emperor, a title that was to shape the politics of the Middle Ages and continue until the 19th Century.

Charlemagne would have returned to France on the ancient road known as the Via Francigena, which passes not far to the west of the abbey, on a route now largely followed by the main road known as the SS2. Unsurprisingly, given that the abbey dates from the same era, a story arose that he had been the founder. There is no contemporary evidence of this, and no dedicatory inscriptions, so the best one can say is that it is not impossible, but not very probable. Among the very oldest parts of the abbey is a chapel probably dating from the 9th-Century which in deference to the Charlemagne legend is known as the “Carolingian Chapel”.

The Medieval Abbey

The building as we see it today was built in the early 1100s – the date of 1118 is carved into the altar step – with money bequeathed by a member of a wealthy local family. There are many interesting features on both the interior and exterior – some part of the original design, some apparently added later, and some which look as if they have been scavenged from older structures.

Like many medieval abbeys, Sant’Antimo acquired significant landholdings, and the secular power that went along with them. One of its properties, which became the residence of the prior, was the rocca or fortress of Montalcino.

But the period of the Abbey’s greatness was relatively short-lived – only a century or so. As Siena expanded its territory southwards, many of the Abbey’s properties were expropriated and with those properties went their rents and other income.

Decline and Rebirth

The end came with the ascension to the Papacy of Aeneas Piccolomini as Pius II in 1458. Before his election Piccolomini had been a famous humanist writer and accomplished papal diplomat (who among other things left an account of a perilous and secret diplomatic mission to Scotland). But importantly he was a local from the small town of Corsignano, not far away. Many medieval and Renaissance Popes enriched their families, but Pius went further and decided to make Corsignano a perfect Renaissance town. He achieved this by demolishing it and having it rebuilt by one of the leading architects of the day. He then renamed it Pienza, after himself. That does explain why today Pienza looks such a beautiful place – it is because it was designed to be so.

Unluckily for Sant’Antimo, Pius was determined to enrich Pienza as well as to beautify it, and he suppressed the Abbey on charges of moral laxity, transferring its remaining assets to the newly-created diocese of Pienza and Montalcino.

At some point after that Sant’Antimo ceased to function as a religious institution and by the 19th Century a local farmer was using the Abbey as a barn and its cloisters as a stable.

In the 1870s the fortunes of the beautiful old building took a turn for the better, as the new Italian state took it on and commenced a programme of restoration which took place over the next century or so. At some point it was reconsecrated, but only occasionally used for services. In the 1970s it was used as a location for the film Brother Sun, Sister Moon, by Franco Zeffirelli.

From 1992 the Abbey again housed a religious community, with the arrival of a group of French monks from the Premonstratensian Order. These were still there in 1999 when we made our first visit, and I remember it as a very peaceful place, with recordings of Gregorian chant playing softly in the interior.

The French monks returned to France in 2015. Although the Abbey is now affiliated to the Benedictine monastery at Monte Oliveto, there are no longer any monks resident there.

Sant’Antimo is now administered directly by the diocese with a view to generating some income – it is available for weddings, the monks’ cells are available as accommodation, the upper galleries of the nave can be accessed for a fee, and there is a shop which sells herbal remedies and similar products, and various medieval-themed souvenirs such as bags or mouse mats with reproductions of old manuscripts. It’s all quite tastefully done, and in the Abbey grounds there is an apiary and a garden where medicinal and culinary herbs are grown. The Abbey now has its own website which you can find here. And you have to pay to park your car.

It is still a wonderful and peaceful place, and well worth the short drive from the more famous attractions of the Val d’Orcia.