Intended as a fortress, then converted into a palace, the Villa Farnese in Caprarola is above all a monument to one of the most powerful families in Renaissance Italy.

The Farnese family accumulated a fair bit of real estate. If you have been to central Rome there is a good chance that you will have seen the massive Palazzo Farnese (now the French Embassy), or the beautiful Villa Farnesina across the Tiber, with Raphael’s famous frescoes. If you have visited Parma you might have seen the elegant “Palazzo del Giardino”, also a Farnese palace. This post is about one of the most remarkable, in the town of Caprarola north of Rome.

The Farnese Family

We met the Farnese family when they were the villains of the story, violently subduing the city of Perugia. This time they get to be the heroes – which is not really surprising since they are telling this story themselves.

Although claiming ancient origins, the Farnese family first came to the notice of history in the 12th Century, with a power base north of Rome. In the interminable Guelph versus Ghibelline wars of the Middle Ages, they generally turned up on the Guelph side, ie the side of the Papacy. It seems they knew where the family’s future fortunes lay.

And stupendous fortunes they were, built on acquisition of noble titles and huge estates, mercenary soldiering on behalf of the popes, and shameless simony and nepotism. “Simony” refers to the buying and selling of ecclesiastical offices and anticipated rewards in the afterlife, like Papal indulgences. “Nepotism” comes from the Latin word for “nephew” and was coined to refer to the practice of Popes granting lucrative high offices – ecclesiastical or secular – to their (ahem) “nephews”.

There were other ways to power. Alessandro Farnese, later Pope Paul III, owed his Cardinal’s hat to his sister Giulia. She was the mistress of Pope Alexander VI, and persuaded him to make her brother a cardinal.

Caprarola

In 1504 Cardinal Alessandro Farnese splashed out on the purchase of the estate of Caprarola in northern Lazio, in the heart of his family’s historical power base. He then commissioned his favourite architect Antonio Sangallo to design and build a large fortress on the site.

We have already met both Alessandro and Sangallo, later in their careers. Forty or so years later, Alessandro was by then Pope Paul III, and, having ordered the subjugation of Perugia by his nephew son Pierluigi, he commissioned Sangallo to build a huge fortress at the south of the town, to keep it that way. All this is described in my earlier post on The Buried Streets of Perugia. But for now the Papacy lay in the future for Alessandro Farnese.

Alessandro’s brief to Sangallo for Caprarola, it seems, was for a military structure, similar to that which he would one day build in Perugia. It was to be a pentagonal fortress in a good defensive position, with bastions that could provide raking fire on attackers. That a prince of the Church thought it prudent to design such a building tells you a bit about 16th-Century Italian politics. When things in the city got a bit awkward, it was time to head to the country estate and pull up the drawbridge.

In any case the fortress was never completed as planned. In 1556 Pope Paul’s grandson, another Alessandro Farnese and another cardinal, had the half-built fortress converted into a lavish country villa by an architect named Giacomo Vignola. It seems that the mood was a bit less bellicose half a century later, but the bastions are still visible at the lower level, and the finished villa retains the pentagonal shape of Sangallo’s original project. And the villa was still used as somewhere to retreat to whenever the Farnese found themselves on the losing side of papal politics.

The Villa

The villa is in the late Renaissance, or “Mannerist” style, and sits on a slope, with formal Renaissance gardens up the hill behind. The front of the building faces south-east, in the direction of Rome. This aspect of the building was doubtless dictated by the topology of the site. It is nonetheless rather appropriate that while the Farnese were enjoying breakfast on their balcony, they were looking towards the city that would always be at the front of their minds – the source of their power, and of threats from rival families. Immediately in front of the building is a massive piazza.

Walking up to the front entrance across the piazza, we were not accompanied by a ceremonial guard, so we felt pretty small. Actually, you would probably feel fairly small even with a medium-sized ceremonial guard, which was presumably the intention.

Once inside you realise that the pentagonal shape is hollow, and that each floor has a gallery around the edge of the central space.

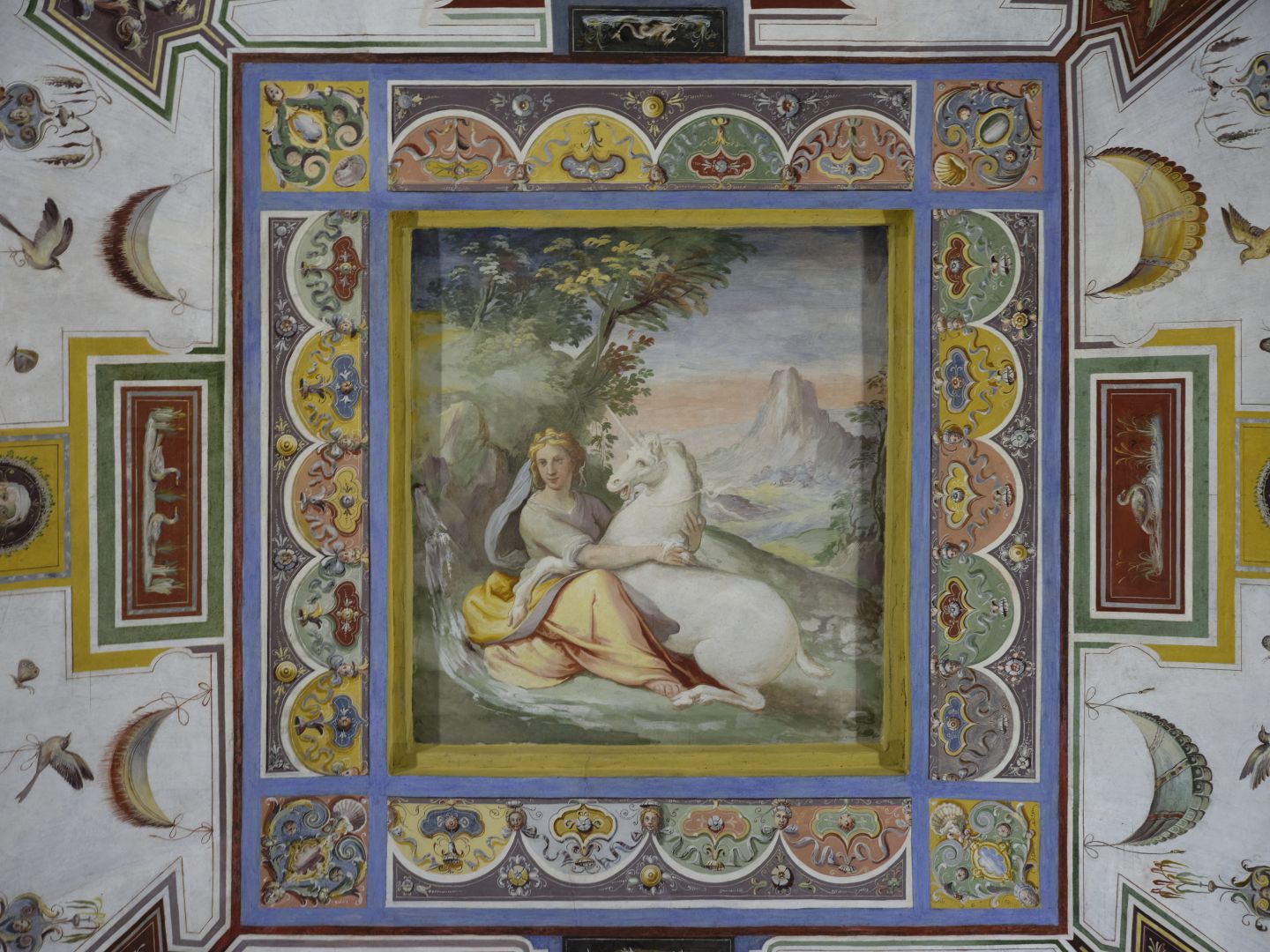

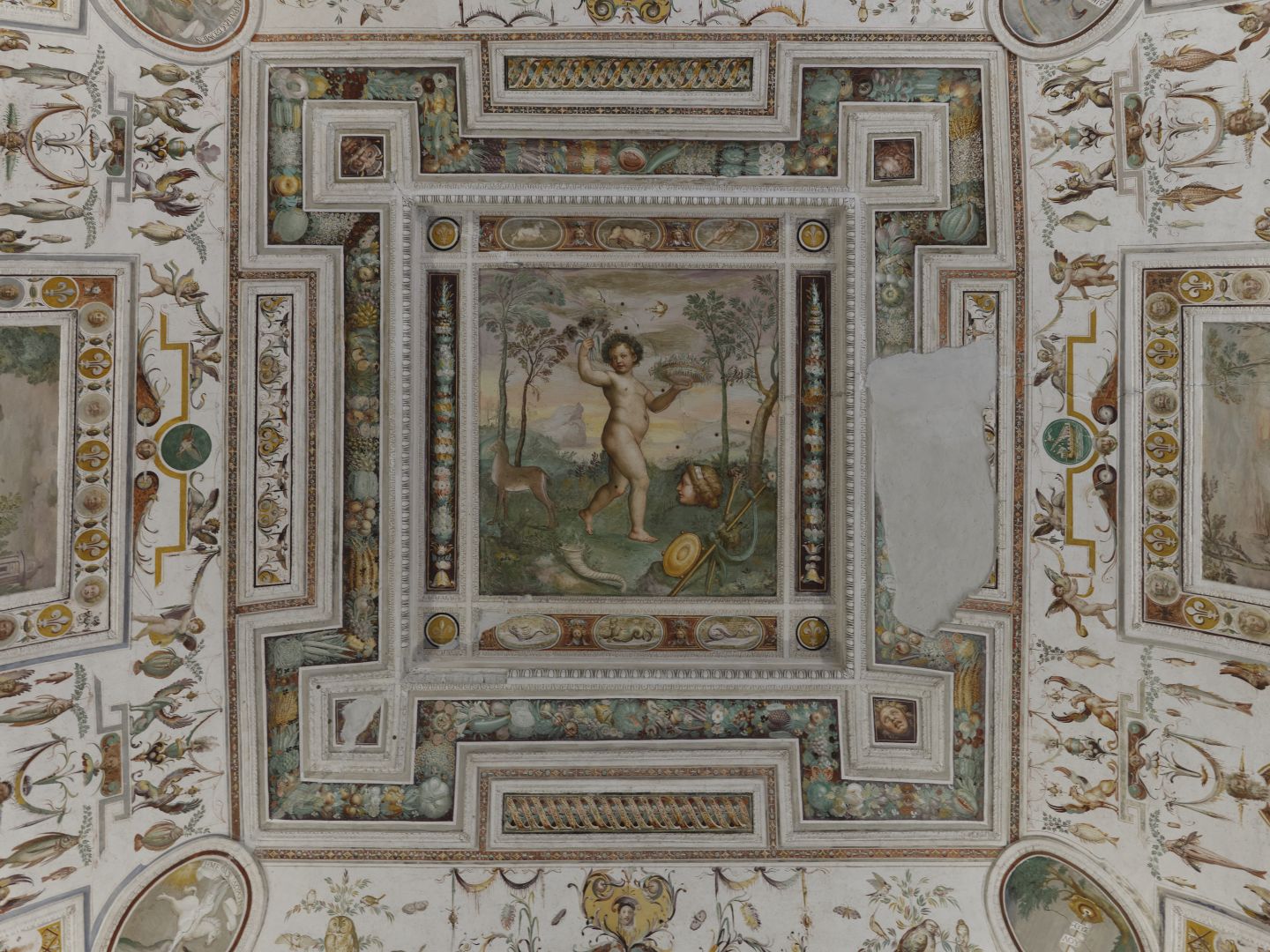

Inside, the rooms are lavishly decorated, with every square metre of wall and ceiling put to use. As is frequently the case in Renaissance palaces, each room has a theme. Sometimes the theme is obvious and sometimes it would need fairly recondite knowledge to spot all the references. Fortunately for those who are not Renaissance humanists, these days there are plenty of explanatory panels.

The Royal Staircase

You access the upper floors by means of the “Royal Staircase”. In this period staircases were an opportunity for architects to show off their skill. The mathematical complexities of their design, the combination of strength and delicacy, and the visual attractiveness of curves and spirals, could come together to show both technical and aesthetic mastery. Vignola seems to have hit all the marks on this occasion.

And of course the walls and ceiling of the stairwell provide more real estate for decoration.

Deeds and Maps

Upstairs the decoration gets even more impressive, and when you enter “The Room of the Farnese Deeds” you realise you are in a Farnese family theme park. Enormous frescoes show great world events in which the family took part. Here the Farnese Pope Paul III and the Emperor Charles V wage war on the Lutherans, accompanied by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and his brother Ottavio Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza.

Here the French King Francis rides out from Paris to meet Charles V on the way to chastise the Belgians (or something), accompanied naturally by Cardinal Farnese, the “ambassador of great affairs”.

It would be a bit nauseating were it not for the sheer pomposity of it all which renders it a bit ridiculous to modern eyes. Freud would no doubt have said that Alessandro was compensating for something. Here is the ceiling, in which almost every panel is a Farnese doing deeds, or angels cheering them on.

The Room of the Maps contains maps of the whole world as it was known in the 16th Century. So no Australia and New Zealand, obviously. It apparently so impressed one of the Popes that he commissioned a similar thing for the Vatican.

The Gardens

As you complete the tour of the villa, you find yourself in the lower of the two gardens – a formal and symmetrical Renaissance garden which is presumably similar to the 16th-Century original. You can imagine the younger Alessandro strolling here, in quiet conversation with some confidential envoy bringing news of developments in the Vatican.

From the lower garden you wander uphill through a chestnut wood. I don’t know what was planted here 450 years ago but the absence of buildings or landscaping suggests that it was intended to simulate a wild landscape. Then you get to the something called the “Secret Garden”, presumably because it was invisible from the main villa. The Secret Garden is approached through a corridor of some pretty exuberant Mannerist waterworks and statuary, starting with a catena d’acqua or “chain of water” which leads up to a pair of colossal statues of river gods.

Beyond the statues are another pair of gardens and a charming building called the “casino”. By most standards this would be considered a substantial dwelling but in the context of the Villa Farnese it is obviously just a little summer house.

After the Farnese

Unusually for a Farnese cardinal, the younger Alessandro left no direct heirs. The villa passed to his relatives, the Dukes of Parma and Piacenza. In the 18th Century the Farnese line died out and their property passed through marriage to the Bourbon kings of Naples.

After the unification of Italy in the 19th Century the villa became the property of the Italian state. For a while the villa was used as a residence for the heir to the Italian throne, but under the Republic it is now a museum.

The “casino” in the upper garden is used as a residence for the President of the Italian Republic. I don’t know if President Mattarella gets to use it very much, but I hope he does. It would be a nice place to get away from the complexities of political life in Rome for a while, just as it was five centuries ago.

2 Replies to “A Little Place in the Country – The Villa Farnese at Caprarola”