Through much of the 19th Century, the wealthiest and most influential family in Sicily was English. A classic history – Princes under the Volcano – tells their story.

I’m going to structure this post around that book, of which I am particularly fond and which I have returned to a couple of times, despite its considerable length. Princes under the Volcano is by Raleigh Trevelyan, and is subtitled “Two Hundred Years of a British Dynasty in Sicily”. It was published in 1972 and reprinted in 2002, and again in 2012. As far as I can tell it is not currently in print, with very few new copies available online, but it seems easy enough to find second-hand editions. There was also an Italian edition (Principi sotto il vulcano) which was very popular and may still be in print.

Raleigh Trevelyan (1923-2014) was an interesting character in his own right. A descendant of the Elizabethan courtier and adventurer Sir Walter Raleigh, and related to the great “Whig historian” G.M. Trevelyan, he was born to a posh army family in British India. In due course he was sent off to boarding school in England. From Winchester College he went straight into the army in 1942. As a young officer seconded to the Green Howards, he took part in the fighting at Anzio in 1944, of which he wrote a harrowing account (he was wounded twice and many members of his battalion died). Later he was part of the British Military Mission in Rome, remaining there for two years and forming a lasting bond with Italy.

After the war he commenced a career in publishing and as a writer himself produced several extensively-researched works on historical subjects. It was this that led to him being approached by a member of the Whitaker family to write Princes under the Volcano.

The “British Dynasty” that is the subject of this book was founded by Benjamin Ingham (1784-1861) and passed through Ingham’s nephew to the Whitaker family. The great bulk – and it must literally have been a great bulk – of material on which the book is based is formed of two collections of papers: firstly those of Ingham himself, and secondly the letters and diaries of Tina Whitaker (1858-1957). Tina also wrote a volume of reminiscences of Anglo-Sicilian political exiles (Sicily and England, still in print in the Italian edition).

Benjamin’s papers are exclusively to do with his business, while Tina’s are full of gossip. This makes the earlier and later parts of the book a bit different in style, but as Trevelyan points out in the introduction, that does rather lend itself to the subject matter. Benjamin Ingham’s career covered the tumultuous years of the Napoleonic Wars and the exile of the Spanish Bourbon King Ferdinand of Naples to Sicily under the protection of Admiral Nelson, then later the failed revolutions of 1849, the convulsions of the Risorgimento, Garibaldi’s campaign in Sicily, the fall of the House of Bourbon and the rise of the Mafia. Throughout it all Ingham records the events around him while grumbling about how bad wars and revolutions are for business.

Tina, on the other hand, was of the generation that didn’t make the money – it spent it. The wife of the wealthiest man in Sicily, related by blood and marriage to both English and Sicilian aristocracy, she entertained kings, emperors and celebrities, and she and her daughters were presented at court in London. The Whitakers knew the family of Giuseppe di Lampedusa, and many of the real people who ended up thinly disguised as characters in Lampedusa’s book Il Gattopardo (The Leopard). Both Ingham’s and Tina’s accounts are fascinating seams to mine for nuggets of insight into Sicilian history, and Trevelyan selects his material well.

Note: until I came to write this post I had not realised that “gattopardo” does not actually mean “leopard” in Italian. It refers to a smaller animal called a serval. Lampedusa’s English publishers decided to change the name to something a bit catchier.

English Merchants in Sicily

What were English merchants doing in Sicily anyway? The answer goes back to Napoleon’s invasion of Spain and Portugal and the subsequent disruption of the Iberian wine trade. England was a great importer of sherry from Spain and port from Portugal, and many English firms were established to produce, transport and sell these wines. The fact that the wines were fortified with brandy, by the way, was less to do with English preference for strong drink than with the fact that the spirit acted as a preservative for the long sea voyage.

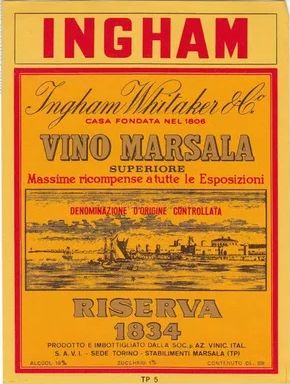

In 1773, an English trader called John Woodhouse had realised that the wines of Marsala and Trapani on the west coast of Sicily, made in a similar way to sherry and port, might also sell well in Britain. It seems to have been a bit of a niche market at first but three decades later the supply of Spanish and Portuguese sherry and port was interrupted by the war, and the trade from Marsala took off.

Life on the west coast of Sicily at the end of the 18th Century would have been tough. Although the Mafia would not take on its modern, organised form for several decades, brigandage and kidnapping were common. Inland there were few roads, and those few were in terrible condition. The writ of the distant Bourbon government in Naples did not really run outside the larger towns. But for a young Englishman with a taste for adventure and a view to making a fortune, it seems to have had many attractions.

The photograph below shows the rugged country inland from Sicily’s west coast – still growing grapes for Marsala wine. At the end of the 18th Century there would have been no modern road here, and quite possibly bandits behind the rocks to take potshots at travellers.

Enter Benjamin Ingham

Ingham was the son of a Yorkshire family that traded in cloth. He arrived in Sicily in 1806 with a view to opening up an export market for their products, but quickly realised that there was more money to be made selling Marsala wine back to Britain and America. As his business grew he sent back to his family for help, and in due course William Whitaker, the son of Ingham’s sister Mary, was sent out to help him.

Ingham was almost a caricature of the dour and unemotional Yorkshireman. A Whitaker family story (apocryphal, I hope) had him, when nephew William died suddenly, writing to Mary saying “Your son is dead. Send me another.”

The replacement nephew was Joseph Whitaker (1802-1884) who seems to have been even more dour than Ingham – not a particularly pleasant or generous person at all, in fact. But the young man does seem to have been an excellent administrator, and it must have been due in part to him that Ingham accumulated the phenomenal wealth most of which Joseph and his family were to inherit.

The British Connection

There were other connections between Sicily and Britain. Many of them date to the period when Lord Nelson was active in the Mediterranean. In fact Nelson seems to have helped kick the Marsala wine trade along with a substantial purchase of wine for his ships – no doubt Nelson was pleased to find that there were British merchants in Sicily to deal with.

Then when the French armies and local revolutionaries chased King Ferdinand IV and his queen out of Naples, it was ships of the Royal Navy under Nelson’s command that evacuated the royal party to Sicily. Also on board were the British Ambassador Sir William Hamilton and his wife Emma, who had already started her famous affair with Nelson.

Note: Queen Maria Carolina of Naples was unlikely to have been a fan of the French Republic. Her sister Marie Antoinette had been decapitated by them.

For a period Sicily remained under de facto British rule, and there were some who thought it would be a good idea to make it permanent, as with Malta. To this end in 1812, a Sicilian parliament and a new Sicilian constitution on the British model were proclaimed. But the idea of Sicily as either a British territory or an independent state under British protection was met unenthusiastically in London. The island was handed back to the Bourbons, the constitution was immediately cancelled and the old regime returned, even more oppressive than before.

The constitution had been an idealistic concept, but hopelessly impractical. To expect a feudal society to adopt a range of liberal institutions at a single stroke was never going to work.

Nevertheless, and perhaps because it had never been tried and shown not to work, the stillborn 1812 “British” constitution occupied a special place in the imagination of Sicilian radicals. Subsequent outbreaks of unrest in 1820, in the failed Italy-wide revolutions of 1849, and the Risorgimento in 1860-61, were always accompanied by calls for its restoration.

Not only that, but Britain itself came to be seen by many Sicilians, rather romantically, as the only foreign power which had their interests at heart. And when Sicilian and other Italian patriots attracted the unwelcome attention of the authorities and had to flee, they often ended up in London.

Garibaldi and “The Thousand”

In 1860, Garibaldi and his famous thousand red-shirted volunteers landed at Marsala and drove the Bourbon forces out of Sicily. The exiles returned, and the Bourbons were replaced by the Piedmontese House of Savoy in the form of King Victor Emmanuel II.

Although there was in theory now a single Kingdom of Italy, for many Sicilians one foreign regime had simply been replaced by another. The catalogue of mistakes made by the new Italian government in handling its new southern territories is long indeed and would take this post in a very different direction. Suffice to say that the Piedmontese Prime Minister Cavour was not interested in any form of autonomy for Sicily, so a bunch of northern Italian administrators arrived who regarded the locals with contempt and horror, and many poor Sicilians found times harder even than they had under the Bourbons. Banditry, bloodshed and the rise of the Mafia were the result.

Throughout all this period of upheavals and excitement, Ingham kept getting richer and richer. He had married a Sicilian noblewoman (and was somewhat bothered by her impecunious relatives). He got into banking, and was said to have lent money to most of the aristocratic Sicilian families. He also got into shipping and before long had his own fleet. He died in 1861, just after Sicily had been absorbed into the new Kingdom of Italy. Part of his substantial fortune – and control of the business – passed to his nephew and long-time associate, Joseph Whitaker.

Joseph and his wife Sophia had had eleven children (a twelfth died in infancy), and on Joseph’s death in 1884 the firm passed to two of his sons, another William and another Joseph, the latter known all his life as Pip. Pip seems to have taken more after his mother than his father – a gentle character much interested in natural history and, later on, archaeology. But it is Pip’s wife Caterina (Tina) who through her papers becomes the central character of the rest of the book.

Caterina (Tina) Whitaker, née Scalia

I find Tina fascinating, even though I suspect that I would not like her very much in real life. Born in England, baptised as an Anglican and married to an Englishman, she was a stickler for form and must have come across as a rather forbidding type of Edwardian snob to those she thought her social inferiors. She divided her time between Sicily and England, and when the Whitakers hosted King Edward VII at their Palermo villa in 1907, she informed the king that he was on “British soil”. And yet her parents were both Italian.

Earlier I mentioned the tendency of Italian patriots to end up in England when they ran foul of their governments (most parts of Italy in the early 19th Century were ruled by foreign dynasties or the Papacy, and even the sort-of-Italian Piedmontese took a dim view of radical nationalists). One such exile was Pompeo Anichini, a member of a respectable Tuscan family; Tina later maintained that they were nobility, but they weren’t really. Anichini became a British citizen, but kept up his links with Italy, trading with Benjamin Ingham, and mixing in pro-Italian circles in London with the likes of Mazzini.

Trevelyan could not find out much about the woman Anichini married, but their daughter Giulia was a striking young woman who had many friends among the italophile English aristocracy. Despite having been born in London and brought up an Anglican, she felt herself to be very much an Italian. However when circumstances allowed her to “return” to Italy later in life she found the reality did not really live up to the dream, and instead increasingly felt herself to be an Englishwoman living in Italy – the fate of many a deracinated exile.

Still in London, in due course Giulia Anichini met a dashing young Sicilian exile called Alfonso Scalia, and married him. Scalia’s father seems to have come from a rather boring middle-class Palermitan family, but his Neapolitan mother Caterina was a real firebrand who joined the Carbonari anti-Bourbon secret society. She passed on her liberal views and her spirit to her two sons Alfonso and Luigi, and when Bourbon troops came to search their house in Palermo for incriminating papers (which Alfonso and his brother were at that very moment destroying), Caterina stood at the door and told the soldiers that they would have to shoot her first. While the soldiers pondered how to proceed, the brothers, having destroyed the evidence, escaped out of a back window.

I find it slightly amusing that the ultra-conservative Tina was named after such a radical grandmother, but according to Trevelyan Tina tended to downplay her paternal ancestry anyway, it not really having been as posh as she would have liked it to be.

In his day job Alfonso Scalia was a captain in the merchant marine. Despite his youth (he was still in his mid-20s), during the uprising of 1849 he commanded revolutionary troops in Catania, shelling Bourbon naval vessels. When the revolution failed, he fled to London, married Giulia and set up a household which became a centre for the exile community, and Giulia’s aristocratic friends.

Return to Sicily

In 1860 Garibaldi swept into Sicily and before the London exiles really had time to organise, Palermo had fallen to the redshirts. However Scalia arrived as soon as he could, and Garibaldi quickly made him a lieutenant-colonel in the artillery; he was later to rise to the rank of lieutenant-general in the army of unified Italy. After Garibaldi’s campaign moved to the mainland, Giulia and Tina (still a little girl) came out and joined him in Naples. Tina would spend most of the rest of her long life dividing her time between Italy and England.

As Tina grew up she trained as an opera singer, and would have been a very good one. By all accounts she was much fêted and was on the verge of a professional career when she became engaged to Pip Whitaker; they married in 1882, and seem to have been referred to in society as “The Pips”. Pip had to spend part of his time running the wine business in Marsala, and was already showing an interest in archaeology, in particular excavating Phoenician remains on the island of Motya near Marsala (“Mozia” in standard Italian). Tina on the other hand was not at all keen on Marsala and spent as much time in Palermo as she could, when she was not back in England.

Shortly after the birth of their second daughter, old Joseph Whitaker died and Pip became the richest man in Sicily. Their house, Villa Malfitano, was one of the most impressive in Palermo, and over the years was visited by the rich and famous, and a few independently wealthy British layabouts who sound a bit like Evelyn Waugh characters. Tina’s diary and letters mention them all (the posher the better) and Trevelyan does a good job of turning the succession of visits into a series of intertwined narratives.

And while Tina was going on about how delightful had been the Princess of This, or how spiteful the Duchess of That, she was tangentially illustrating Italian and European history.

During the First World War the older of Tina’s daughters, Norina, married a military man, General Antonino di Giorgio. During the 1920s di Giorgio became Minister for War in Mussolini’s government, although he does not seem to have been a committed fascist himself, and died before the outbreak of the Second World War.

The End of the Dynasty

Pip died in 1936, and the now-elderly Tina, cared for by her two daughters, found herself in a precarious position as war approached, given her British nationality. Despite Tina’s late son-in-law having been a minister in one of Mussolini’s governments, several relations and family friends were associated with the anti-fascist side, and there are stories of arrests and people living in great anxiety. The three moved between Sicily and Rome for a while, but saw out the last couple of years of the war in Rome. Tina’s papers record tumultuous events around the fall of Mussolini, the oppression of the German occupation, and the privations of the late wartime period for the population of Rome.

Tina died in 1957, Norina having predeceased her in 1954. Delia, the other daughter, lived on until 1971, long enough to be interviewed by Trevelyan as he researched the book. She died just as it was published. Their magnificent home, the Villa Malfitana, avoided the fate of many grand mansions in Palermo, being neither destroyed by allied bombs nor allowed to fall into ruins and be converted into slums through Mafia corruption. I regret that I have not photographed it myself, but here is a photograph from Wikipedia:

After Delia’s death the family wealth went into the creation of the Joseph Whitaker Foundation (Fondazione Giuseppe Whitaker), preserving the Villa Malfitana and also the results of Pip’s Phoenician excavations at Motya. You can visit the English-language version of the foundation’s website here, with some photographs of the interior of the villa. It is well worth visiting the website to see the extraordinary luxury in which the Whitakers must have lived. Note that the Giuseppe Whitaker talked about in the text of the website was in fact Pip, not Joseph Whitaker senior.