Ravenna contains some breathtakingly beautiful art and architecture, miraculous survivals of a fascinating period in Italian history – fifteen hundred years ago – of which relatively few artistic and architectural records remain elsewhere. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site. For a while it was the capital of the Western Roman Empire, so if my previous post was not historical enough, this one should redress the balance.

The Place

Ravenna is on the Adriatic, near the mouth of the Po. Just north of Rimini, it was on a major military route in antiquity. Not far away is the little river Rubicon which marked the boundary past which a Roman General could not approach Rome without Senate permission. When Caesar defied the senate and crossed the Rubicon, he remarked that the “die is cast” (alea iacta est). Ravenna was an important port, and shortly after he defeated Mark Antony and became emperor, Augustus built a separate military port in Classis (modern Classe), a mile or so to the south, from which Rome could project power into the northern Adriatic.

Over the centuries, silting of the northern Adriatic has moved the coastline a few kilometres east, where a modern industrial area has grown up. The port of Ravenna was a target for allied bombing in World War 2, and while some of the irreplaceable cultural sites in the old city were damaged or destroyed, it may be that the displacement of the coastline and the growth of the new town is what saved the others.

Capital of a Declining Empire

How did Ravenna come to be the capital? By the end of the 4th Century, the Western Empire was at a tipping-point into terminal decline – economic, military and political. The frontiers were coming under pressure from increasing populations of “barbarians” – populations on whom Rome was becoming ever more dependent as a source of men for its armies. As agricultural productivity started to fall, the spread of a nasty new strain of malaria from Africa exacerbated the problem in the south, and the effects would eventually be felt through every tier of the economy.

The Eastern Empire, ruled from Constantinople, was where the action was. That left the West as the domain of the also-rans, and it showed. Most of the emperors of the West in the later 4th Century were either gormless nonentities increasingly dependent on military strongmen, or the strongmen themselves overthrowing each other in regular coups d’état. They didn’t even spend much time in Rome – for much of the 4th Century the effective capital of the West was Mediolanum (modern Milan).

Then in 402, after the Visigoths besieged Milan, the Emperor Honorius moved the seat of government down the Po Valley to Ravenna. The perceived advantages of the move were all military – the marshes surrounding it to the west should have been a defence against land attack. Since none of the barbarian nations had a navy worth the name, the military port at Classe would guarantee open supply lines to the Eastern Empire, and the Via Flaminia was an overland military route to Rome.

Goths and Arians

But the Western Empire had only 75 years or so to live. Rome was sacked by the Vandals in 410 (they simply bypassed Ravenna on their way south). In 476 the last western emperor – the derisively-nicknamed Romulus Augustulus (the little Augustus) – was deposed by one of his generals, the German Oadacer, who styled himself not Emperor, but King of Italy. Traditionally, historians like Gibbon marked this moment as the fall of the Empire. In fact, and to the extent that anyone in Italy at the time cared, the Western Empire was subsumed into the Eastern, and Oadacer, it seems, was careful to acknowledge the authority of the Emperor in Constantinople even though he was effectively independent. But the eastern Emperor Zeno cared, and he encouraged Theodoric, the Byzantine-educated leader of the Ostrogoths, to invade Italy and overthrow Oadacer in his turn. After inflicting a number of defeats on Oadacer’s forces across Northern Italy as far as Milan, Theodoric met Oadacer in Ravenna in 493. There, at a ceremonial banquet, Theodoric drew his sword and killed Oadacer with a single blow. Ravenna was henceforth the capital of the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy.

Which was a pretty big deal, and a more definitive break with the past than the deposition of Romulus Augustulus, whatever Gibbon might have said. For all his barbarian origins, Oadacer had led what was more or less a military coup by Rome’s own forces. Theodoric, by contrast, led not just an army but a people, who, like the Lombards and Franks that followed, formed part of the mass movement of peoples that marked the end of the classical period, and fundamentally changed the genetic, linguistic and artistic development of Italy.

The Goths were Arian Christians, deemed heretics by the Catholic Church (the final schism between the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox branches of Christianity lay in the future). As with many such religious disputes, there was no real disagreement over anything in the gospels, or the central Christian message of redemption. The clash instead was between the complex theological arguments which had been erected on that simple foundation. And no question was more vexed than that of Christology – the nature of Christ. Was the Son of the same substance as the Father and co-eternal with Him (the Catholic position), or like any son, did he have his own separate existence, albeit partly divine (the Arian position)? From the former comes the recondite doctrine of the Trinity, and the latter, perhaps because it required fewer intellectual gymnastics, seemed to appeal to the Goths. However they were a tolerant lot and even when they ran the place they didn’t really mind what the Latins and Greeks thought, especially as they probably didn’t really care what all the fuss was about.

There are two great architectural relics of this particular period in Ravenna. The first is the Arian Baptistry, an octagonal building with elaborate mosaic decorations. On the ceiling there is a representation of the baptism of Christ in the Jordan by St John the Baptist. To the modern eye, accustomed to conventional representations, there are some departures from the iconography to which we are accustomed. One is that Jesus is portrayed as a beardless youth. Another is that he is completely naked, rather than decorously draped. And the third is that the River Jordan is personified by a sort of pagan water spirit. (Edit: when I first published this post I speculated that these iconographic differences were “Arian” in character. However later we revisited Ravenna we saw the older Orthodox Baptistery and apart from the lack of a beard, it seems much the same.)

The second great relic from the Arian period is the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo. This is a church built by Theodoric in the early 500s as his palace chapel. It is a large, light, airy building with a great deal of wonderful mosaic decoration – including a Virgin and Child and processions of male and female saints. But given the history of the place, there are two decorations worth particular attention. One is a depiction of the Three Kings approaching the Infant Christ, and their extraordinary costume – bright red Phrygian caps and elaborately-decorated trousers. I’ve seen the costumes described as “to emphasise their oriental origins”, but also, much more appealingly, as “Gothic dress”. If the latter, then this would be such a rare thing – an illustration of how Gothic noblemen looked, by contemporary craftsmen competent enough to do so accurately. Also, despite what pasty-faced modern teenagers might think, it shows that Goths did not wear black.

At the other end of the church, high up, are depictions of palace buildings, lined with arches. These arches once contained pictures of human figures, presumably Theodoric himself and other worthies. However at some later point, after the suppression of Arianism and possibly on the instructions of Pope Gregory the Great, the central arch was blanked out in gold, and the other arches were reworked with images of curtains, covering the figures in an attempt to remove them from history. It seems that the Catholics were less tolerant of the Arians than the Arians had been of them. But the craftsmen given the job were not terribly careful, and if you look carefully, in several places you can see the hands or fingers of the censored figures, like the spare foot of someone otherwise airbrushed out of a photograph of Stalin’s politburo.

Justinian and Theodora and the Exarchate

In 527 Justinian became Emperor in Constantinople. Probably the greatest emperor of the post-classical period, he came from humble origins in what is what is now Albania. Apart from a major codification of imperial law and an attempt to heal religious differences between Constantinople and Rome, for our purposes his principal achievement was the reconquest of Ostrogothic Italy.

Like many English-speaking readers, I first came across this bit of history in Robert Graves’s historical novel Count Belisarius, where we meet the noble and talented general of the title, the equally talented (but less romantic) general who followed him, the elderly eunuch Narses, and the Emperor Justinian and his Empress.

While Justinian was – to put it mildly – a strong personality, his choice of consort makes him look somewhat plain vanilla in comparison. The Empress Theodora was the daughter of a bear-trainer at the hippodrome, and as a young woman had been a performer in what might euphemistically be called a sort of cabaret. She added a distinct element of cruelty and ruthlessness to Justinian’s reign – and almost certainly was responsible for its longevity as well. Theodora was tailor-made to become one of Graves’s arch-villainesses, like Livia in I, Claudius. And as with Livia this is in part due to Graves’s desire to write as would a contemporary witness, and his use as a result of contemporary historians. In Theodora’s case the historian in question was Procopius (c.500-565) and he clearly hated both Justinian and Theodora, stopping at nothing if it would blacken their reputation. After quoting a particularly pornographic description by Procopius of one of the young Theodora’s theatrical routines, John Julius Norwich sums it up quite even-handedly, firstly by calling Procopius a “sanctimonious old hypocrite” who is clearly enjoying telling the tale, and secondly by observing that “Theodora was, as our grandparents might have put it, no better than she should have been. Whether she was more depraved than others of her sort is open to question.”

As a result of the campaigns of Belisarius and Narses, Ostrogothic Italy returned to Byzantine rule, and once again the choice of capital in the West fell on Ravenna, governed by an exarch or representative of the Emperor. But another invading people had arrived – the Lombards – and by the late 6th Century they controlled considerably more Italian territory than did the Exarchate. Before long most of the Exarchate was absorbed into Lombard domains before they in their turn were conquered by the Franks.

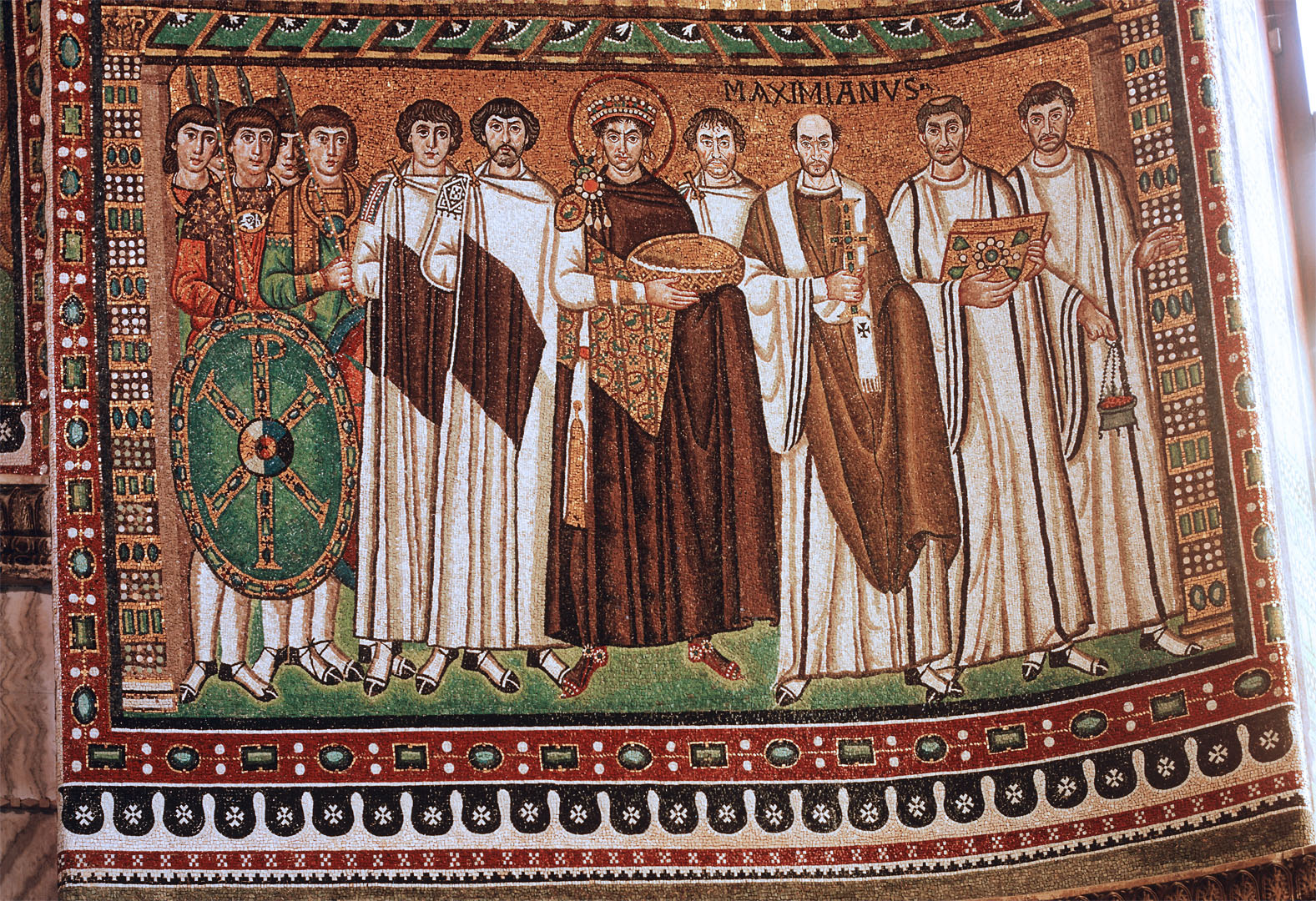

During this tumultuous period, a rich citizen of Ravenna commissioned the building of the Basilica of San Vitale. It is a jewel-box of 6th-Century architecture and decoration, and would be worth visiting just for that. But it contains two large mosaic panels, one of Justinian and his attendants, and one of Theodora and hers, completed in their lifetimes.

While it seems implausible that they actually sat for them, the individuality of these portraits, not just of the principals but of the other characters, and the force of personality they show, argues strongly that at some remove, they were based upon somebody’s actual observation of their subjects.

The bald chap standing next to Justinian and identified as “Maximianus” was Bishop of Ravenna at the time and it must therefore be considered a likeness. The bearded fellow with a pudding-basin haircut, standing immediately to the left of Justinian, is someone I have seen identified as Belisarius, although most writers do not do so. To look into their faces across a gap of 1500 years is extraordinary. And it must be said that Theodora does not look like someone in whose bad books you would want to be.

In 787, two hundred and sixty years later, the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne visited San Vitale, and looked upon the face of Justinian. You can tell that he was impressed, because he used San Vitale as a model for his new imperial chapel at Aachen. Not only that, but the chapel at Aachen re-uses some columns scavenged from the ruins of other buildings in Ravenna.

Classe

At around the same time as San Vitale was erected, in the military port of Classe a large church was built and dedicated by Maximianus to his predecessor Saint Apollinaris, the first bishop of Ravenna and Classe. The Church of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, as it is called in Italian, now sits quietly some distance inland thanks to coastal silting, with no trace of the old port fortifications visible. Inside, the iconography is of the saint as a shepherd leading his flock.

The real genius of the artist was to place it all in beautiful green fields. It is a peaceful place to visit now, both outside and inside, and it must have been a peaceful place to sit when it was new, while outside empires fell and kingdoms rose.

A note on the photography

The best way to take photographs of things high up on walls is to get the building owners to let you build a scaffold to raise the camera to the same height as the subject. And you should use bright white photographic lighting to ensure you get true colour rendition.

Lacking the right sort of connections and equipment, I took all these from ground level and under the sort of tungsten lighting you normally get in these places. As a result they all had a “leaning backward” perspective and a strong yellow cast. I’ve tried to reduce both of these in Photoshop, by applying perspective correction and a slight blue filter.

Further reading

A good recent source on the politics of the 4th and 5th Centuries is Imperial Tragedy, From Constantine’s Empire to the Destruction of Roman Italy, AD 363-568 by Michael Kulikowski, Profile Books, 2019.

Another good source I have recently come across, although published 30 years ago, is The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity AD 395-600 by Averil Cameron, Routledge, 1993.

Note: in 2022 I picked up the story in this post: The Lombard Invasion and the Byzantine Corridor.

Note 2: the photographs accompanying this article were taken in 2008. In 2023 I returned with different equipment and took a different set, and visited some different places as well. You can find that article here.

5 Replies to “Ravenna at the Fall of the Empire”