The late Sixth Century saw some extraordinary developments in Italy. Almost the entire country was overrun by the Lombards, except for a narrow strip of territory – the “Byzantine Corridor” between Rome and Ravenna. You can still see where, in the modern landscape, the “Corridor” ran.

In my post about Ravenna at the Fall of the Empire I wrote of the invasion of Italy by the Goths, the partial reconquest by Byzantine forces, and briefly mentioned the subsequent invasion by the Lombards. This post picks up the story, and looks at how it played out in central Italy.

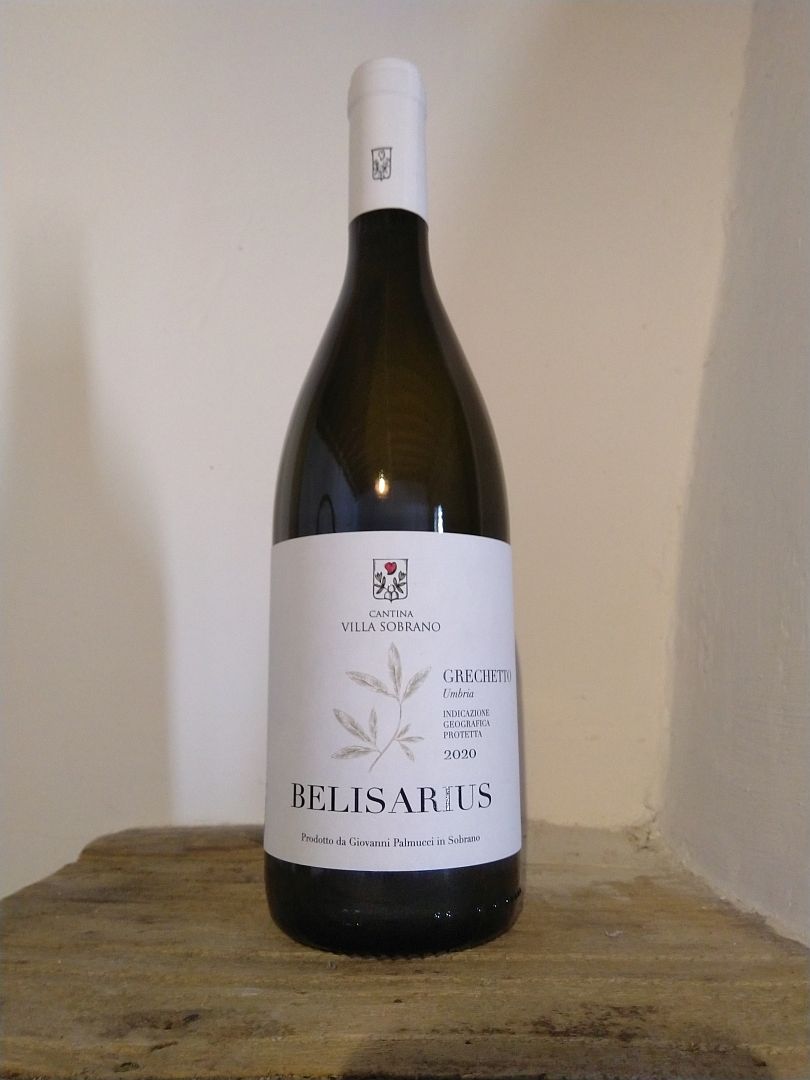

The Byzantine forces under Belisarius and Narses had successfully regained much of Italy from the Goths for the Byzantine Emperor Justinian. Obviously the conflict is not entirely forgotten in Umbria, going by this wine label I found:

But the period of the Gothic War of 535-554 was absolutely ruinous for Italy – not just due to military action. In 536 the Earth suffered the worst climate event in recorded history when a volcanic eruption (the location is uncertain) caused two years of severe global cooling followed by drought. That was on top of existing climate change as, due to changes in the solar cycle, the world left the “Roman Warm Period” and entered the “Medieval Cool Period”. Crops failed and famine was widespread. Then came the so-called “Justinian Plague” in 540-541 (probably bubonic plague). All that was on top of the spread of malaria from the south.

Deliberate debasement of the currency (these days they call it “quantitative easing”) which had been going on for many years, reduced people’s purchasing power. Depopulation, impoverishment and a general breakdown in administration were inevitable. The population shrank, education almost ceased, technologies were forgotten, the great cities emptied, productive agricultural land reverted to swamp or woodland, health and life expectancy declined, and things were generally horrible. Revisionist modern historians avoid using the term “Dark Ages” to refer to the centuries after the fall of the empire (presumably to avoid offending people who identify as Visigoths and Vandals) but the Dark Ages sound pretty dark to me.

And while the war left the “Roman” Byzantines nominally in charge, it was a pyrrhic victory. The attenuated power of the local representatives of distant Byzantium – the Exarchs of Ravenna – was not up to the task of resisting the next threat.

The Lombards

And the next threat was the Lombards, or in their own language, Langobards or Longobards. If you agree with me that it sounds a little bit like the English words “long beards”, you are absolutely right. The Langobards came to the notice of history in what is now southern Sweden, Denmark and northern Germany, where they were speaking a language closely related to Anglo-Saxon. And it seems that they did indeed have long beards, or at least the men did, so that is what they called themselves.

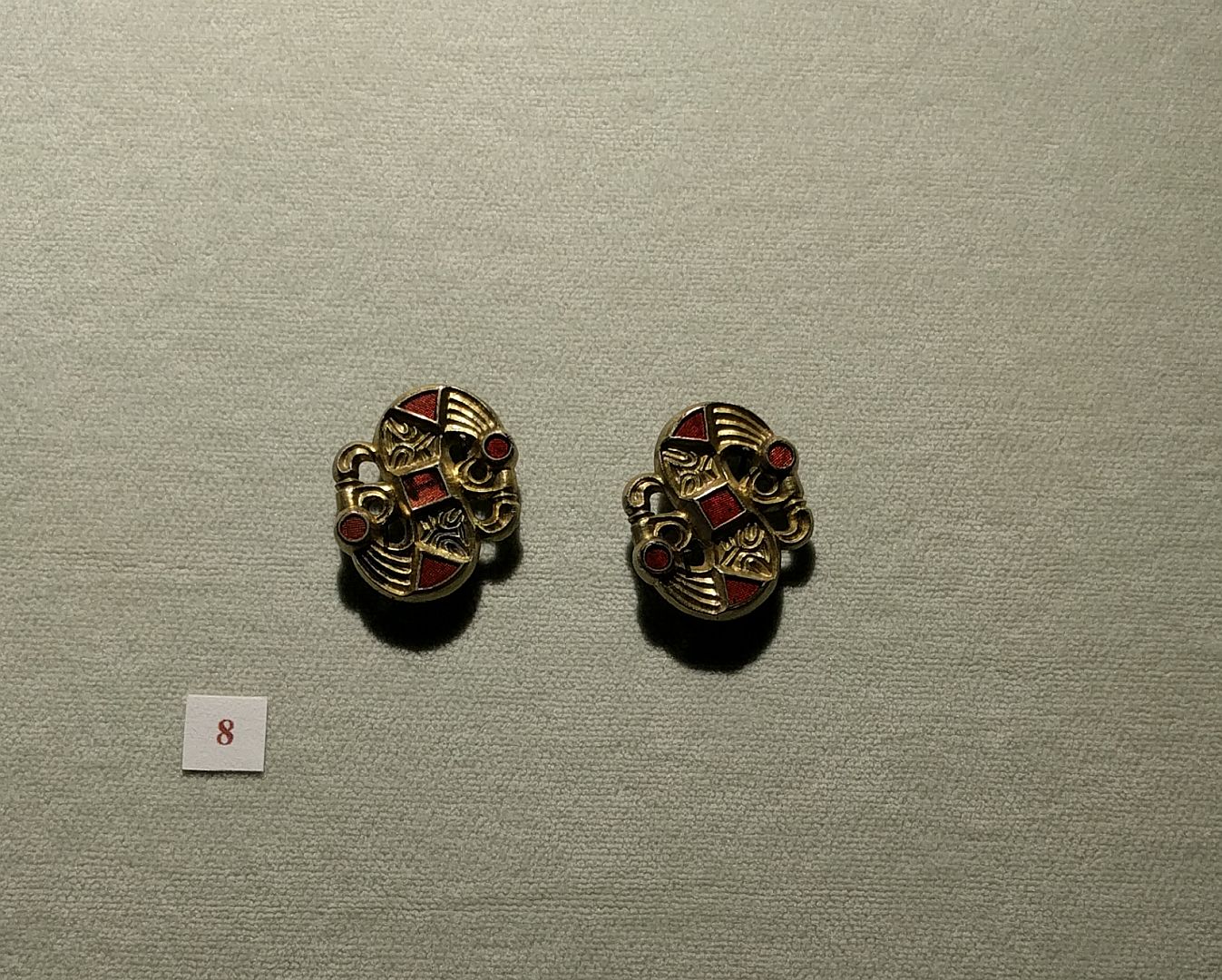

After a few hundred years of drifting southwards, and under pressure from other aggressive populations to the east, the Lombards (as I will now refer to them with their Italianised name), found themselves in what is now Austria and Slovakia around 568 AD. They entered devastated and depopulated Italy across the Julian Alps (in modern Slovenia) and were virtually unopposed. A modern town close to where they entered Italy is Cividale del Friuli in the far northeast, which has some Lombard archaeological remains and an excellent museum of Lombard culture which I highly recommend.

As we saw earlier, thanks to the devastation caused by the Gothic Wars, the Lombards were pretty much pushing at an open door. But nevertheless the speed of their expansion through Italy was extraordinary. Only two or three years later almost all of northern Italy was under their control (a much larger region than the modern “Lombardy”) and Lombard duchies had been established further south in Tuscany, Spoleto and Benevento.

Here is a map of Italy after these duchies were established.

You will see that the nominally Byzantine control of Rome continued, that the Exarchate of Ravenna was threatened, and that they were connected by a narrow strip of territory. Italian historians call this the Corridoio Bizantino or “Byzantine Corridor”.

Conflict and Truce

In Umbria, as the Lombards extended their territory westwards from Spoleto, they captured the Via Flaminia, cutting the Byzantines off from the historic military route between Ravenna and Rome. But somewhere in the Martani Hills the Lombards stopped, and the Via Amerina, not far to the west in the Tiber Valley, remained under Byzantine control. It was this road, originally a series of pre-Roman provincial roads between towns, that became the narrow thread linking Ravenna and Rome through hostile country: the Byzantine Corridor.

At first the corridor was created and defended by force of arms. Later, a truce between Lombard and Byzantine/Papal authorities regularised the borders, but there were probably a few skirmishes from time to time.

So how narrow was the corridor? In places very narrow indeed, it would seem.

Linguistic Evidence

Working out where the edges of the Byzantine Corridor lay is difficult; they didn’t put up signs beside the roads. But as with Anglo-Saxon and Celtic place-names in Britain, one form of evidence for boundaries, and hence the extent of Lombard dominion in Italy, is linguistic.

A few years ago it occurred to me to wonder about the origin of the word borgo, common in Italy and meaning a small town, or an area on the edge of a larger town. This is clearly not of Latin origin, but the same Germanic word that you find in Hamburg, Gothenburg, Peterborough, Canterbury and Edinburgh. And lots of other burgs, borgs, boroughs and burys. What was such an obviously Germanic word doing in Italian?

It turns out that borgo and several other Italian words associated with locations are indeed Germanic. Some might have been derived from Gothic or Frankish, but most are probably Lombard.

Another such word is gualdo. The letters “gu” in Italian were used in Italian to render the initial “w” sound in Germanic languages, such as “Gualtiero” for “Walter”. So if you see an Italian word beginning in “gu” followed by a vowel, it probably has a Germanic origin. Gualdo comes from the same origin as the German wald meaning wood or forest, as in Schwartzwald for “Black Forest”.

There are a number of places in Italy either called Gualdo, or with names containing that word. They all seem to be in areas that were once part of Lombard dominions. While such places were presumably named for being in or near woodland, the term is also associated with military outposts, suggesting that they would have been on the borders of Lombard territory.

In the Martani Hills in Umbria is a pretty little town called Gualdo Cattaneo. From the linguistic evidence just discussed, this may well have been an outpost in wooded country on the edge of Lombard territory, in this case the Duchy of Spoleto. I understand that the earliest surviving records are from after the period of the Byzantine Corridor, but the name tells you that the area was certainly Lombard, so the idea that this was originally a border outpost is appealing. The photograph below, taken from the south, shows that it was on elevated ground facing west into Byzantine territory – exactly what you would expect of such an outpost.

The picture below, taken from a bit closer, shows the defensive situation of the town, even if the current fortifications are clearly from the 14th Century or later (rounded fortifications generally post-date the introduction of cannon to warfare; cannon balls are more likely to bounce off them).

The Byzantine Corridor Today

The photograph below shows the Middle Tiber Valley, looking north from Todi towards Perugia (I recommend you click on it to open a larger version in a new window). It is up this valley that the Via Amerina ran, and so you are looking at the actual Byzantine Corridor. Today’s pretty agricultural landscape must look very different from the semi-wilderness of the 6th Century though. The Via Amerina more or less followed the route now taken by the E45 motorway, clearly visible on the eastern side of the river, but back then it would have threaded between swamps and woodland, and passed through the ruins of Roman-era towns by then abandoned.

This photograph really helps one envisage just how narrow the “Byzantine Corridor” was, here in central Umbria. Gualdo Cattaneo, on the edge of the Lombard Duchy of Spoleto, is in the hills at the right of the photograph, about 12 kilometres from the motorway. To the left of the Via Amerina is the Tiber (marked by a double line of trees), and beyond it steep hilly country. Further west still was the Lombard Duchy of Tuscia, or Tuscany.

Here is the same area on a map. The E45 motorway runs down the middle, following approximately the same route as the ancient Via Amerina. Gualdo Cattaneo is on the right. The town of Deruta through which the road passed had been completely destroyed in the Gothic Wars and Lombard invasion – indeed its very name derives from Latin words implying ruin.

That puts it all in perspective. Up and down this valley would have come Byzantine troops, and Imperial and church officials, trying to maintain contact between Ravenna and Rome. They would have hurried from the protection of one fortified town to the next, keeping an eye on the nearby woodlands for signs of an ambush by Lombard troops, or maybe a party of leftover Goths.

South of Todi there seems to be some uncertainty over exactly where the Corridor ran. I’ve done a bit of poking about in the hills there, and I’ll make that the subject of a separate post in due course.