Iris Origo (1902–1988) should be much more famous than she is. Not just as a writer, historian and biographer but as a philanthropist, agricultural reformer and a war heroine.

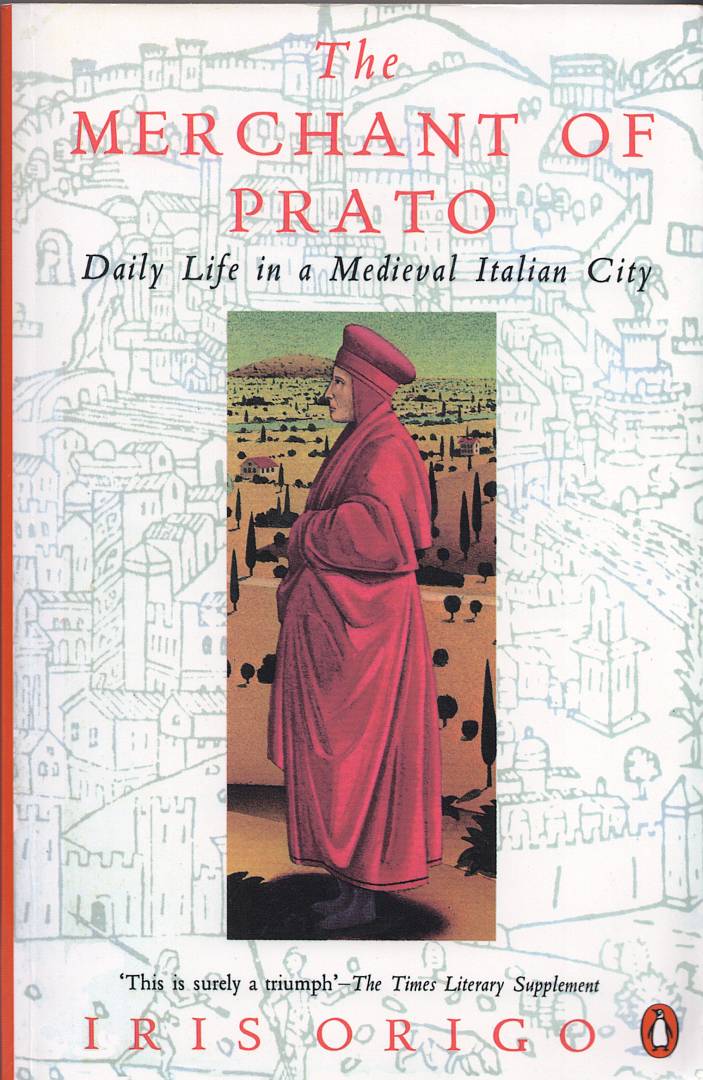

I first encountered Iris Origo about fifteen years ago when I bought her book The Merchant of Prato. The Merchant of the title was Francesco di Marco Datini (1335-1410), a resident of the city of Prato near Florence. Datini was a successful businessman with interests across Europe, especially Papal Avignon, although he also imported Cotswolds wool for the Florentine textile industry.

Datini kept meticulous records of his numerous letters and commercial documents, and in his will he directed that they be kept and stored in his house. Over time “storage” seems to have been rather broadly interpreted, as they were discovered in 1870, stuffed into sacks under the staircase – but still in his house, so the terms of the will had arguably been observed. While doubtless a few learned monographs were produced, the material had to wait until 1957 to be introduced to a wider audience in the form of Iris Origo’s book.

I really enjoyed the book and have re-read it a few times. It could have been rather boring, but her writing style is engaging. She manages to synthesise a compelling narrative from an enormous amount of source material, and combines painstaking scholarship with a deep understanding of the historical and cultural context in which Datini lived. In particular Origo manages to show real empathy for her distant subjects while not ascribing feelings to them beyond those supported by the historical evidence.

We actually have a couple of representations of Datini’s likeness. Like many wealthy merchants with a nervous eye on the church’s ban on lending at interest, Datini donated to good causes including paying for religious art, and in a painting by Filippo Lippi he is shown imploring the intercession of the Virgin Mary on behalf of a group of fellow-citizens.

If I can produce enough relevant photographs of Prato, I might do a separate post one day on Datini, but now I have a more compelling story to tell.

Who was Iris Origo?

So who was this writer, so obviously of extensive learning and considerable intellect? The back cover of The Merchant of Prato called her a Marchesa or Marchioness, which is to say above a countess in the order of Italian nobility, but below a duchess. It also turned out that she had never really been to school, let alone university.

She was born in Birdlip, Gloucestershire in 1902 to Bayard Cutting, a very wealthy American diplomat from New York, and Lady Sybil Cutting, daughter of the 5th Earl of Desart, an Anglo-Irish aristocrat. Alas, Bayard contracted tuberculosis and despite traipsing around the world to various health resorts in search of relief, he died in 1910 leaving his wife and young daughter alone but independently wealthy.

Bayard had developed strong internationalist ideas and before his death had asked Sybil not to bring Iris up either in America or England, but in an environment where she would not develop a strong sense of nationality. It is hard to say how successful this was, as Iris clearly always thought of herself as English, spending a lot of time in England (and some in America) in the 20s and 30s and being presented at court as a debutante. Moreover, she was to live in times when men with guns were liable to demand to see one’s passport, which rather forces the decision on one. But as we shall see she would spend more time in Italy than anywhere else.

An unusual childhood

Sibyl therefore decided to settle in Florence, arriving there in 1911 with the nine-year-old Iris in tow. Since the days of the 18th Century Grand Tour, and right up until the Second World War, there was a substantial British (and American) colony in Florence. Given the city’s artistic heritage, the English-speaking colony was rather self-consciously intellectual – like other expat groups though, it tended to factions and feuds.

Sibyl Cutting would have made a bit of a splash on arrival, as she rented the Villa Medici in Fiesole, one of the grandest Florentine addresses in terms of location, luxury and history. Fiesole is a town on a hill which overlooks Florence from the north, and in the mid-1450s Cosimo de’ Medici had built a villa there with magnificent views over the city. With Sibyl and Iris in residence, the villa quickly became one of the main social centres of the English colony, and Sibyl was to buy it outright in 1923.

The photograph of Fiesole below was taken from the viewing platform at the top of the Brunelleschi dome on Florence’s duomo. The Villa Medici is the square white building in the middle of the picture.

The free-thinking Bayard had not wanted Iris to attend a normal school, and she mostly did not, although when she was briefly enrolled in a school in London at the age of 12 she was assessed to be three years ahead of other girls of the same age. Instead she was schooled partly by a succession of governesses, partly self-educated by being given free run of the library at home, and partly by her mother’s intellectual friends, including the American art historian and fellow Florentine resident Bernard Berenson.

And it was on Berenson’s recommendation that Iris was sent for personal lessons with Professor Solone Monti on three afternoons a week. Monti taught her Greek and Latin and western literature, rather in the way that a Renaissance humanist scholar might have tutored the child of a prince. She learned Latin and Greek grammar by completing exercises while travelling to and from Monti’s home on the tram.

One of the many English people who drifted into the Cutting’s circle was an architect called Cecil Pinsent. A rather diffident young man, he set up a business with another Englishman restoring and redecorating the old buildings owned or rented by the expatriate colony, and increasingly designing their gardens. Apparently they were not very good at the practical side to start with, but learned on the job. It was not long before Sybil Cutting asked Pinsent to work on the gardens and interior decoration of the Villa Medici.

Sybil sounds like a difficult character – an increasingly self-obsessed and neurotic hypochondriac. As Iris grew older she was probably happy to spend more time in England away from her mother, where despite an understandable lack of self-confidence, she moved in some fairly exalted literary circles, meeting and talking with the likes of Virginia Woolf and T.S. Eliot.

Marriage and La Foce

It might have come as a surprise therefore when this quiet, brainy young woman on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Group married a young Italian aristocrat: the Marchese Antonio Origo. It might have been even more of a surprise when the newlyweds announced that they were sinking their combined capital into the purchase of a large but very run-down estate in a distant corner of southern Tuscany – the Val d’Orcia.

Nowadays the Val d’Orcia is one of the top tourist destinations in Italy, with some of the country’s most iconic views. I have photographed it many times, including on two visits this year. As indeed have hundreds of thousands of tourists. And as I’ve said elsewhere, modern visitors understandably think of the region as a land of milk and honey, or at any rate a land of pecorino cheese, salami and wine. But a century ago it was impoverished. Education rates were low, while disease rates, especially of those diseases associated with poor nutrition in children, were high.

There were a few reasons for this. One was soil degradation – the Val d’Orcia, heavily wooded in antiquity, had been deforested by the Etruscans and the Romans. What soil there was, already rather thin, was in many places eroded away to the underlying clay, and poor farming practices only made the erosion problem worse. Lack of education, conservatism and suspicion of outsiders hindered the introduction of more scientific farming techniques.

All of these ills occurred within, and were compounded by, the system of sharecropping known as mezzadria. As the name suggests, tenant farmers handed over half their crop (il mezzo) to the landowner. Traditionally, mezzadria was supposed to be a two-way street, with landowners having reciprocal responsibilities for various aspects of their tenants’ welfare. However by the early 20th Century, the great majority of landowners were absentees living in towns, handing over the management of their properties to factors (farm managers) whose job it was to maximise profits.

Into this sailed Antonio and Iris, two idealistic amateurs determined to be the old-fashioned, caring type of proprietors. In Antonio’s case this meant studying and introducing the latest scientific farming methods, while in Iris’s case it meant medical care and education for the children.

La Foce lies near the southern edge of the old Grand Duchy of Tuscany, in sight of the fortress of Radicofani that guarded the border with the Papal States. It was near the old pilgrim road called the Via Francigena of which I have written elsewhere. Along the old pilgrim routes, various charitable institutions would build hospices for pilgrims and other travellers, and the main building of La Foce was such a one, dating from the late 1400s.

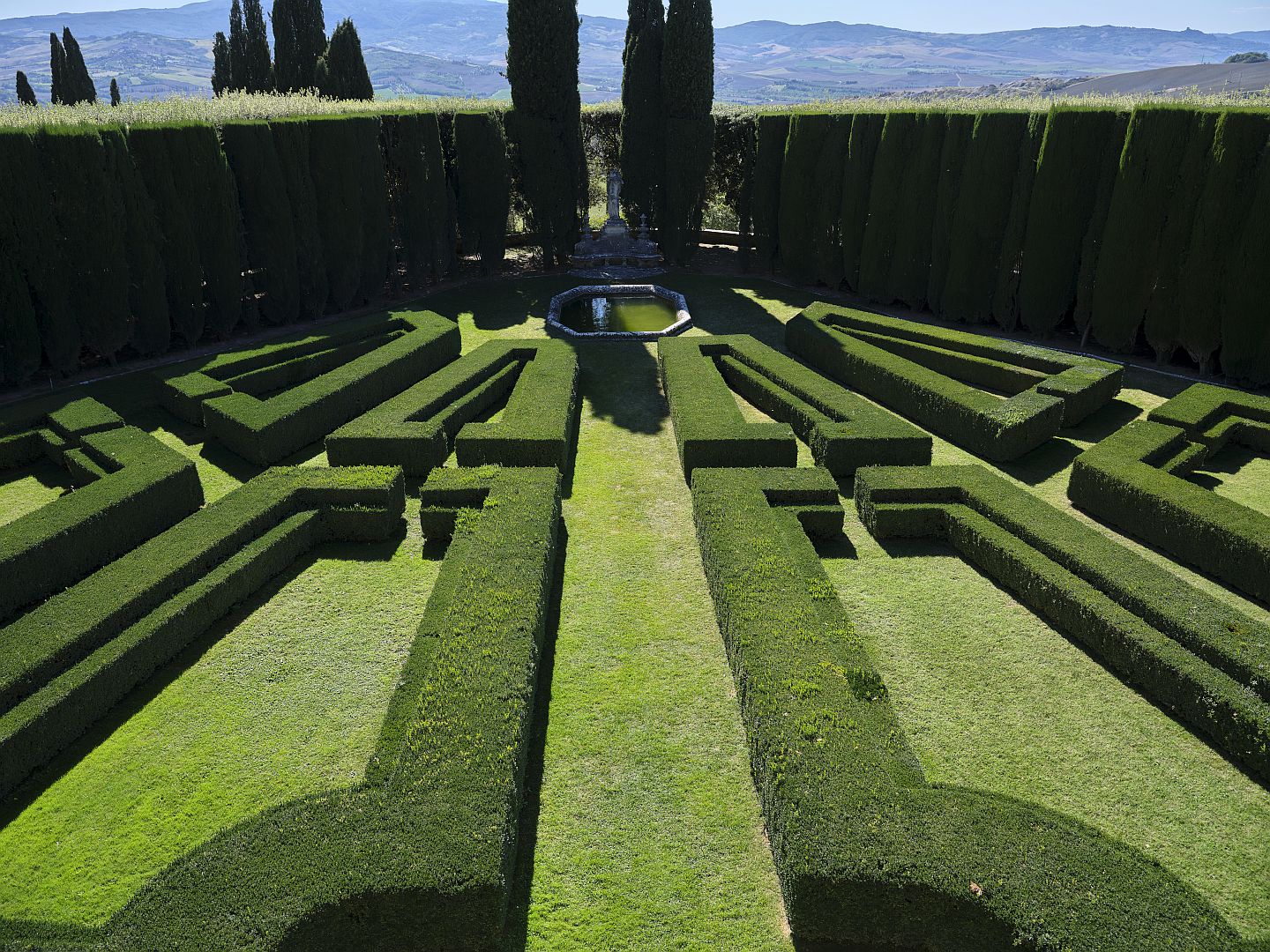

In the 1920s the old building was much neglected, without water or electricity, and the grounds were described as being like a lunar landscape. Iris’s choice of an architect to restore and extend the buildings, and lay out the gardens, was obviously going to be Cecil Pinsent.

Pinsent extended the building with a new wing at the rear, and in doing so realigned it. While the original wing faced the west and the old road, the new wing had a panoramic view south across the valley towards Monte Amiata.

As a birthday present for Iris, her American grandmother paid for water to be piped from a distant spring, and with a secure water supply now available, Pinsent could start laying out the garden. Photographs from the 1930s show that the modern garden is largely unchanged from Pinsent’s original design.

In 1925 Iris and Antonio had a son, Gianni, to whom Iris was utterly devoted. Alas, he was to die of meningitis shortly before his eighth birthday. Pinsent designed a small chapel in the grounds in which Gianni was buried (as later were his parents). Much later they had two daughters, one of whom, I believe, still lives at La Foce.

Antonio’s efforts to rehabilitate the estate and improve the productivity of the farms were starting to show results, as were Iris’s initiatives with the children of the estate, including starting a school and a clinic. These projects happened to be consistent with the rural modernisation programs of the Fascist government, and La Foce became something of a propaganda showpiece for the regional Fascists. Not unnaturally this caused the Origos to be viewed with suspicion by some people after the war.

But in fact Iris’s Anglophone circle was strongly anti-fascist, and Antonio was a conservative aristocrat, a reserve army officer and an Italian patriot rather than a Fascist. Like many of his class he would have thought the Fascists a better choice than the Communists at first, changing his views as the harm Fascism was doing to Italy became apparent. After the fall of Fascism, when Germany became the enemy, it would be clear which side he was on. But in the 1930s, politics was a subject that was avoided at the Origo dinner table.

War comes to La Foce

As war approached, Iris recorded in her diaries the increasing hostility towards Britain and the expatriate community. These diaries were published posthumously in 2017 under the title A Chill in the Air. Once war broke out, she was viewed with suspicion by the authorities, but protected by her marriage to an Italian and by the fact that she had an American as well as a British passport (America was to stay out of the war for two more years). Iris tried unsuccessfully for a while to get some sort of volunteer work and eventually managed a job with the Red Cross in Rome, helping families on both sides of the conflict to get news of sons who had been taken prisoner.

Later, Iris made representations to the Italian authorities to be allowed to take in at La Foce children evacuated from northern cities like Milan and Turin, by now under heavy bombing. Eventually this was agreed to and small groups of traumatised and in some cases orphaned children began to arrive, to be housed in the farm buildings closest to the main house.

After the Italian surrender in 1943, many thousands of allied prisoners of war were released or escaped and the Germans – after some frightful atrocities – left Rome and began retreating up through central Italy. Word spread among the POWs, partisans and Italian army deserters that La Foce was a place in which they might find aid and advice. There are some quite surreal accounts of escaped POWs creeping through the woods above La Foce and suddenly finding themselves addressed by a tall woman dressed in tweeds who would hand them a bit of food and a map, and in upper-class English tones would briskly advise them where to go to hide, or where the allied lines were believed to be, and how to avoid German patrols. On at least one occasion, Iris was out at the back of the house on just such an errand while Antonio was out at the front casually engaging a German patrol in conversation. I’m surprised no-one has made a film of it.

Some of the POWs made the dangerous journey south to rejoin the advancing allies; others preferred to hole up until the allies got to them. The wooded country around the base of Monte Amiata was a major partisan stronghold, and some POWs went and joined them there. A good many POWs and Italian deserters were sleeping rough in La Foce’s own woods.

If the word had got around in partisan circles that the Origos could be relied upon for help, then it would not have been long before the Fascists found out too, and the Origos were denounced in local Fascist news sheets. To have been caught helping the resistance by the Germans would have risked arrest, deportation to a concentration camp or summary execution, so to survive must have required a good deal of both agility and luck.

Escape with the children

Inevitably the allies – Americans, British, Indians and New Zealanders – arrived in the Val d’Orcia, with aerial bombing and artillery fire from both sides. One day the Germans came and informed the Origos that La Foce was to be requisitioned as a command post, so the time had come to get the remaining families and the refugee children to safety. Iris and Antonio gathered them all together and led them on foot to Montepulciano, about ten kilometres away.

The photograph below shows Montepulciano from the little town of Montefollonico. La Foce is beyond the hills at the distant right of the picture, so it would have been over these hills that Iris and Antonio led the refugees.

The roads were mined, and subject to artillery fire. The group walked past the bodies of dead soldiers, and hid in the cornfields when they heard shellfire. Eventually, exhausted and desperately thirsty, with the adults carrying the smaller children, they arrived outside the walls of Montepulciano. The Germans had left, and the refugees were taken in by friends in the town. Again, I don’t know why someone did not make a film of this – I can see Vivien Leigh as Iris and Dirk Bogarde as Antonio.

There was one peripheral element of this story that did end up on film, in a small way. Commissioned into the Royal Engineers, Cecil Pinsent returned to Italy in 1944 as part of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Commission – one of the “Monuments Men” who tried to recover art works lost and stolen during the fighting, which inspired the film of that name.

Iris the writer

Iris started writing seriously after the death of her son. It is therefore a bit poignant that her first published book was Allegra, a biography of the poet Byron’s short-lived illegitimate daughter, published in 1935. She brought out a couple more biographies before the war interrupted her writing career. You can find a complete list of Iris’s books in the Wikipedia article – I don’t propose to list them all here.

Her first really popular book was published in 1947. War in the Val d’Orcia was based on her wartime diaries and did a great deal in England and America to create more positive feelings towards Italy after the years of hostility.

In the late 1940s word got around in publishing circles that there existed in Italy a trove of letters from Lord Byron to his last mistress, Countess Teresa Guiccioli, but that the current owner, an elderly descendant of the Countess, was reluctant to allow access to them. Iris was asked by her London publishers to visit the owner and seek access to the letters, which she did without much expectation of success. Whether it was her manner, the fact that she had already published on Byron, or that she too was an Italian aristocrat of sorts, the old gentleman agreed. Thus was born her next book: The Last Attachment: The Story of Byron and Countess Guiccioli. I’ve got it – I have to say that although Iris is scrupulously objective, neither Byron nor Teresa comes across as particularly likeable.

In 1967 Iris was elected as a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and in 1976 she was appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. Antonio died in 1976 and Iris died in 1988.

La Foce Today

After the war the mezzadria system started to break down. The system as a whole was irrevocably tarnished by the injustices suffered by so many, and the Origo’s efforts to have been good proprietors did not really help them. The new republican government of Italy was keen to see the end of mezzadria , and applied its own inducements and penalties. Probably the most inexorable force was economic: the large-scale movement of the rural workforce to work in the industrial cities of Northern Italy, which brought fundamental changes to Italian society over the course of the 1950s and 60s. The estate was now worked by hired labour and a few remaining mezzadri who, on the Origos’ own initiative, received 70% of what they produced rather than the old 50%. After Iris’s death her daughters sold off about two-thirds of the estate.

A visit to the gardens is very rewarding and we would thoroughly recommend it. They are open a couple of times a week for guided tours in English and Italian, and you need to book on their website (see below). Comparing the gardens as they are today with photographs from the 1930s it is clear that they are more or less exactly as they were after Pinsent established them. At the end of the tour you end up in a small shop where some of Iris’s books are on sale.

I do not have figures to hand, but it seems that by the 1970s many of the La Foce farmhouses which the Origos had modernised in the 1930s would have been vacant and derelict. Then along came the agriturismo movement. These days the houses are mostly agriturismi at the end of cypress-lined roads where foreign visitors and Italians escaping the cities enjoy the idyllic Tuscan scenery. Few visitors would be aware how much the beauty of the modern landscape owes to Iris and Antonio.

More Reading

My principle sources for this post have been Iris’s own writing, and a biography by Caroline Moorehead published in 2000.

If you are interested in reading more, then Moorehead’s biography or Iris’s War in the Val d’Orcia would be good places to start.

I would also recommend La Foce’s own website, which features some impressive aerial photography of the estate as it is now, and some archive photographs which show the Val d’Orcia in its barren days before the Origos started to improve it. A page marked “References” contains external links to various articles. Italy seems to specialise in idiosyncratic website designs which are not always easy to navigate, and some of the outbound links are broken, but it is worth persevering with.

Postscript

I mentioned earlier my impression that Iris’s wartime experiences would have made a great film, and while checking something in Caroline Moorehead’s biography I found that in the 1980s a film based on War in the Val d’Orcia had been contemplated – something I had forgotten. Apparently Iris’s opinion was that she should have been played by Meryl Streep. That would have worked.