A few weeks ago I was browsing a second-hand bookshop in the inner-Melbourne suburb of Carlton, when my eye fell on a slim book with the title Camera and Chianti. Now one of the reasons I write about photography and Italy is that these are subjects I like to read about myself. So naturally I took it down from the shelf, and for the vast sum of $6.25 Australian I became its new owner and was soon heading to a nearby pub to celebrate my find with a glass of wine at an outdoor table.

The book turned out to be an account of a journey around Italy, with photographs by the author, a chap called Francis Sandwith. It was published in 1955 but in the text there are references to the forthcoming coronation, and the photographs appear to show spring foliage, so my guess is that the actual trip was in the first half of 1952. In those days of post-war austerity, the costs needed to be offset by assistance from the Italian State Railways, and Ilford film. Also doubtless a sign of those times, the book is cheaply printed on poor quality paper, and the reproductions of photographs are not the best.

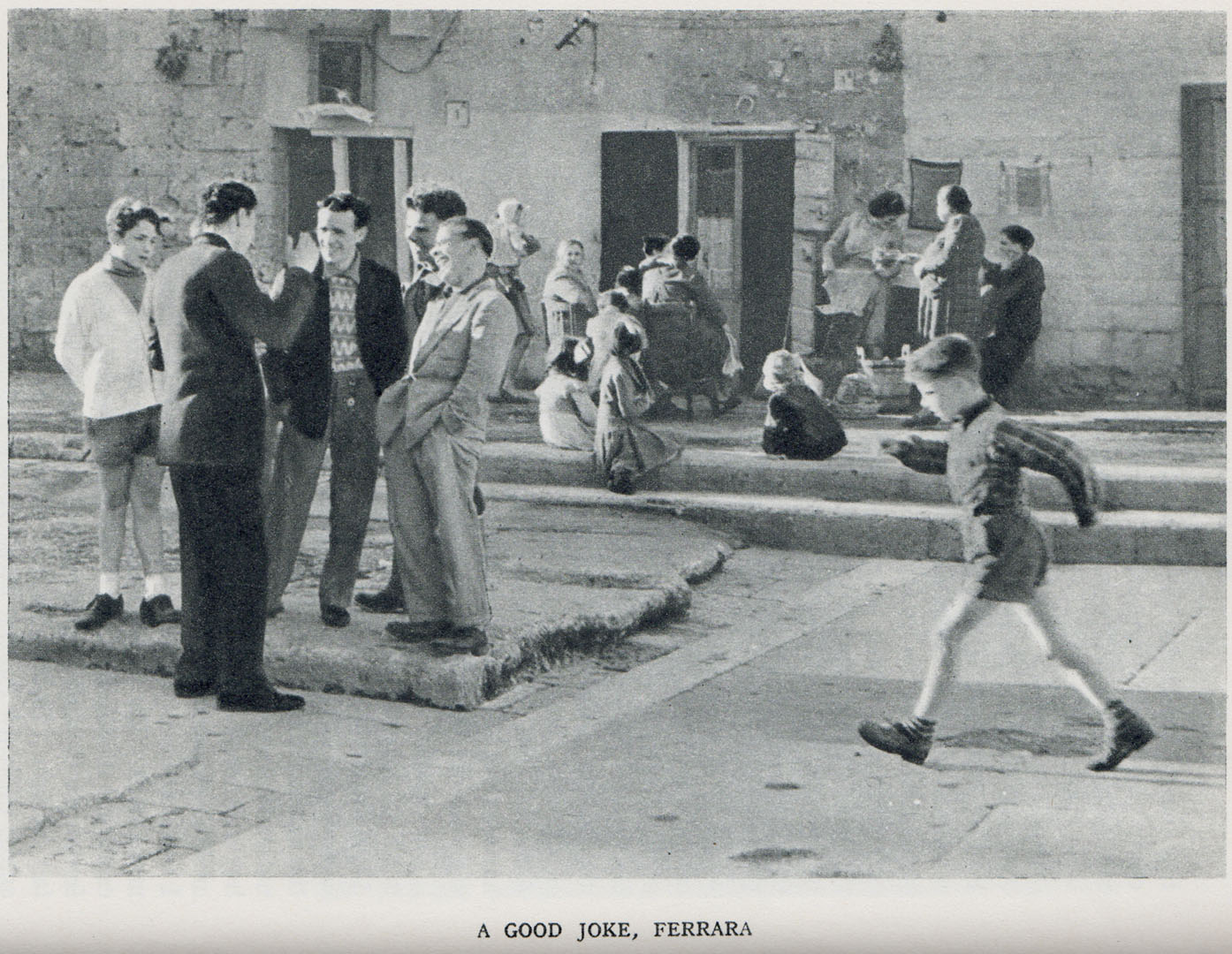

I was mildly surprised, looking at the contents page, to see that despite the title, he did not go anywhere near Chianti or even Tuscany. As I read, though, it became clear that he used the term “Chianti” to refer to any locally-produced Italian wine in a straw-covered flask, red or white, just as people might once have referred to any dry red wine in a straight bottle as “claret”, whether or not it came from Bordeaux. In fact, his trip started in Milan, then continued to Padua and Ferrara, then went south via San Marino to Puglia and Calabria, and ended in Naples via the Amalfi Coast.

Francis does not seem to have left much of a mark on literary history – he has no Wikipedia entry – but I did find a website here which appears to have been set up as an online repository of works by Francis and his daughter Noelle, an artist, photographer and ethnographer who worked extensively in Australia and the South Pacific. The website gives his year of birth as 1899, but not a year of death. According to the website, he was educated at Oxford, and went on to hold editorial positions on several newspapers in England and the Dominions, including Ceylon and South Africa. As a photographer he did advertising work and photography for Country Life and the Morning Post, and ran the photography department of a major advertising agency.

Unfortunately the website appears not to have been completed – sections titled “Library” and “Gallery” are not linked to any content. And there is no apparent way to contact the creator of the site, who is presumably a descendant of Francis Sandwith. So, not having been able to seek permission, I hope that the few reproductions of Francis’s photographs in this post – scanned from the book – can be considered fair dealing for review purposes.

Francis comes across as a nice chap. He was a journalist and photographer, not a writer of books. In fact he only seems to have produced two books – this one, and one in the 1930s of night photographs of London, called London by Night. That one seems to be a bit of a classic, no doubt using what would now be called large format cameras using sheet film or even glass photographic plates.

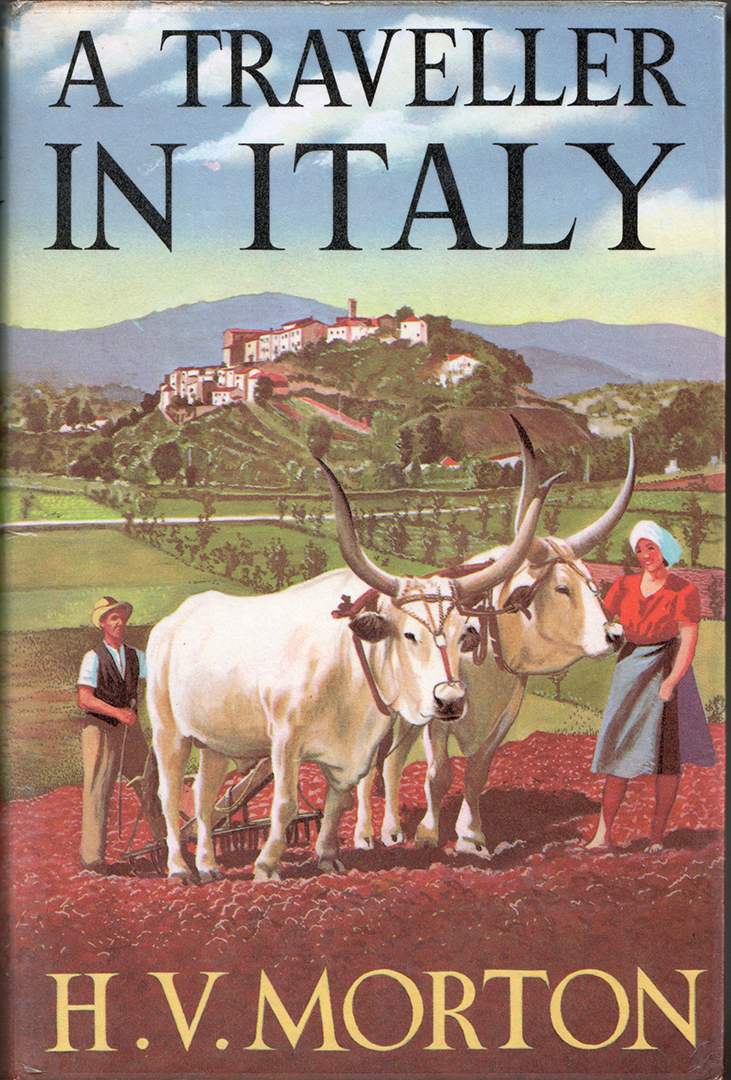

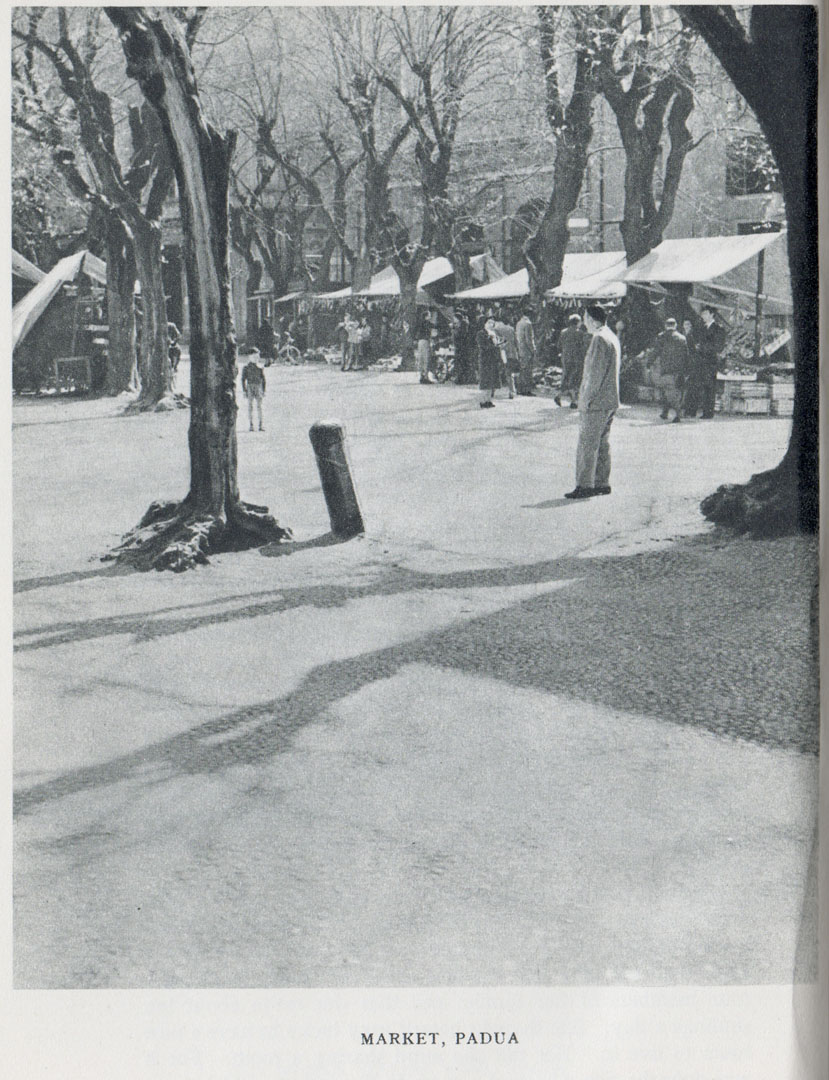

I was pleased to see that like H.V. Morton here, Francis thought the market in Padua was a wonderful timeless place. And like me here, he thought it a good place for photography.

We made our way to the market in the Piazza delle Erbe. It was a gay scene. Pigeons flew over the stalls covered with huge red umbrellas and coloured awnings. As in London, children eagerly bought peanuts for the birds, which clustered on the cobbles, and there was also a colleague reaping his harvest with a miniature camera. Italians love children. It was a delight to watch hard-bitten business men stop to watch a scene, which they must have looked at hundreds of times, and the tides of pleasure that suffused their faces.

The market was very tidy. Everything was spick and span, orderly and quiet. The stall-keepers, mostly women, sat at the back of their stalls, on which the goods were displayed with an eye to colour and design, with an apparent air of indifference. They did not bother to glance at a foreigner, for they had seen many foreigners come and go in recent years. About them there was an eternal quality, like the ancient stone bronzed with the sun of centuries, a timelessness, so that whether a sale was made to-day or to-morrow did not matter greatly.

OK, so he might have used a few clichés, but he was a journalist after all. And we should remember that he was writing for a generation whose opportunities for travel had been severely limited by the Depression, the war and the subsequent period of austerity. What might seem a bit hackneyed to our more fortunate and blasé generation might well have come across as fresh and new to them.

He has a dry and rather self-deprecating humour as well. In Taranto he was being shown around by the Director of the tourist office, a prominent local photographer, and an interpreter.

In southern Italy the traveller is overwhelmed with hospitality. Your host will see that every moment of the day is occupied and is reluctant that your night should be spent in solitude and without suitable entertainment. So I was not surprised, for I had been warned about these old southern customs, when the interpreter inquired with a gay and confidential air whether I would like a young and beautiful signorina to share the midnight hours. The interpreter and the photographer, both delightful young men, gazed at me with warm understanding and sympathy. The Director hummed a little tune. I was a little embarrassed, for I did not like to let down the reputation of British photographers for enterprise, but I am in the middle fifties and was tired with the heat and travelling. So I excused myself by saying that I was too old.

Cameras and technique

A particular highlight for me is that throughout the book he also describes the process of taking his photographs, and at the end he lists the cameras and film that he used. Although he describes his cameras as “miniature”, only one of them, an Ilford Advocate II, used 35mm film. The other three were all what would now be called medium format, using 6cm-wide 120 roll film. One was a twin-lens reflex Microcord, a British version of the Rolleicord. He also used two Zeiss Ikonta folding cameras. This was a pleasure to read because I have a couple of these in my collection:

The smaller one dates from the 1940s, and the larger from the 50s. With relatively little work I have restored both of these to working order and I have taken pictures with them. The lenses are very sharp, all things considered.

The only two things wrong with them is firstly that the lenses are very contrasty, and secondly that the colour balance isn’t quite right on modern (Fujichrome Velvia) film – there is a bit of a blue cast. For lenses designed before colour film was really a thing that isn’t too surprising. Given the sharpness of my results, I’m not sure how to explain the poor quality of the reproductions in the book. It could be the how the book itself was printed, or it could be that by his own account Francis was mainly using fast black and white film, which would have produced quite grainy results. Film emulsion technology still had some way to go in the 1950s.

Francis also took some colour photographs on his trip. Alas none are reproduced in the book. Images in online bookshops show that the original dustcover was a colour version of the “Calabrian maidens” but unfortunately my copy has lost its cover. However it is nevertheless interesting to read Francis’s descriptions of the limitations of colour film in those days. The postscript in the book says he was using a colour negative film called “Pakolor” which according to my online searches was an English film based on an Agfa chemistry. A description here suggests that the film had an effective speed of ISO 10 which is very slow indeed by modern standards – requiring much longer exposures for a given light and aperture. So a tripod, or bright sunlight, would have been necessary. However Francis also explains that the high contrasts and harsh light encountered in the middle of the day were also unsuitable for colour film and that he could therefore only use it in limited circumstances. On one occasion in Taranto he took some pictures having forgotten that he had colour film in the camera, and the results were too badly underexposed to be used.

As I said, after buying the book I went to the pub, or as Francis would doubtless have put it, I repaired to a nearby hostelry, and enjoyed making his acquaintance over a glass of wine. From memory it was a Barolo, which is probably close enough, given his somewhat elastic definition of Chianti. Cheers, Francis.