Celestine V was history’s most reluctant pope. I visited the harsh and beautiful landscape from which he came, and where he had lived as a hermit.

Abruzzo, for those who have not been there, is the very mountainous region on the eastern side of the Italian peninsula, about halfway down. It is due east of Rome, and can be reached from there quite quickly by a modern road that goes through many long tunnels and over some spectacular tall viaducts. Until the 20th Century though, if you were in Rome and wanted to get there in a hurry, you might have been better off going by sea, thanks to the mountains.

Despite being on the same latitude as Rome, Abruzzo is officially and historically part of il mezzogiorno or the South of Italy. “Officially” in the sense that the Italian Government groups several regions together for statistical and policy purposes, on the grounds that they share similar economic and social problems, and are the subject of various targeted schemes to try and relieve those problems. And “historically” because before Italian unification in the 1860s, those regions were part of what was variously called the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Sicily, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies – ruled for its last few hundred years by a branch of the Spanish Bourbon family, one of the most reactionary regimes in Europe. Over a hundred and sixty years later, that history still casts a long shadow.

The Apennines define Abruzzo: high mountains, poor soils, a harsh climate – and earthquakes, lots of them.

For many centuries, the principal economic activity was transhumance – the moving of animals, mostly sheep and goats but cattle too, up into the high country at the end of spring to graze on the mountain pastures, then back down again when the cool weather arrived. Some of the distances travelled were in the order of several hundred kilometres. Transhumance is still happening, but rather than huge herds of animals blocking all the roads, it happens in trucks at night.

These days Abruzzo hosts some of Italy’s wildest national parks, in which are to be found eagles, boars, bears and wolves. I didn’t see any, but there are plenty of road signs warning one to be careful not to hit a bear (I was careful, and didn’t).

We had made a couple of visits to the region in the past; I went there a third time in July 2023 in search of some cooler weather than we were getting in Umbria. I was staying in a place called Caramanico Terme. Italy is full of these spa towns, the glory days of which were mostly in the 1950s and 60s. It seems that back then you could get a doctor to prescribe you a cure at a spa, for your liver or whatever, and the result was a holiday subsidised by the Italian public health system. It was a racket, and eventually the government put a stop to it.

Since then, Caramanico has done better than some; its proximity to Maiella National Park has allowed it to reinvent itself as a centre for outdoor sports, and so instead of elderly people with liver problems shuffling along, the town is full of younger people with extravagant calf muscles striding purposefully along. The spa itself is closed.

On the evening after I arrived I went out for a stroll and an aperitivo. As soon as I got outside I smelt smoke in the air; the sky was a bronze colour, a light snow of white ash was falling, and people were gathered in the street looking at the sky, in a way that Australians are familiar with. It didn’t take long to establish that there was a wildfire on Monte Morrone, the large mountain between Caramanico and Sulmona. That put paid to one option for the next day, which was a visit to the principal hermitage of Pope Celestine V.

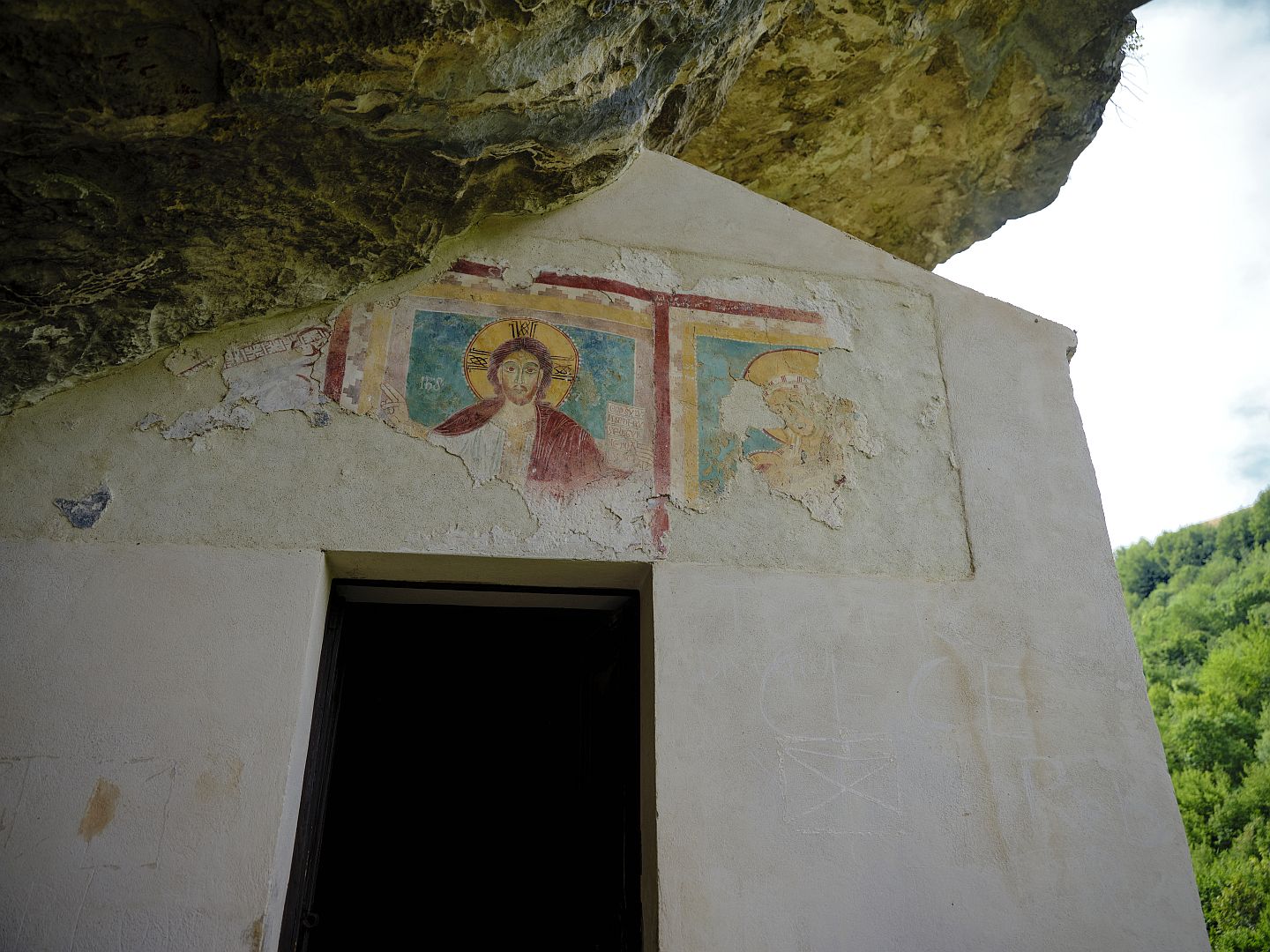

In fact, a visit to Celestine’s main hermitage on Monte Morrone, even if there had been no fires, would not have been all that satisfying, as it has been significantly enlarged and embellished over the intervening centuries. But all was not lost – not far from Caramanico is another hermitage that he lived in for five years, which is still pretty much in the 13th-Century condition to which Celestine himself restored it. It is called Eremo di San Bartolomeo in Legio.

Pope Celestine V

Who was Celestine V, and why would I want to visit his hermitage? Born Pietro Angelerio and later known as Pietro da Morrone, he was easily the least suitable pope in the history of the papacy (note: I have no opinion on the suitability of any recent popes on doctrinal grounds; this is a history blog, not a religious one).

Back to Pietro. Born to a poor farming family in the 13th Century, he became a monk and lived an extremely ascetic life as a hermit on Monte Morrone and other places in the area, attracting followers and gaining a reputation for piety and simplicity. He came to the attention of papal circles when he made a journey to visit the then pope in person and seek approval for establishment of his order, later known as the Celestines.

Then the pope died, and for various reasons, including plague in Rome and the usual one that several of the cardinals wanted the job themselves, no agreement was reached on a successor for a couple of years. Pietro wrote to the college of cardinals, then meeting in Perugia, telling them that they risked damnation if they didn’t make up their minds. No doubt thinking “job done”, Pietro went back to being a hermit, only to stick his head out of his cell one morning to see a delegation outside informing him that he had been elected the next pope. Actually, two delegations. The King of Naples, of whose territories Abruzzo was part, had also heard the news and could not pass up the opportunity to get involved in the fun.

Dismayed and at first flatly refusing (one story has him dragged out from under the bed by his heels), Pietro was eventually persuaded on dubious theological grounds that he did not have the option to refuse, and very reluctantly agreed to become pope, taking the name Celestine V. It didn’t end well. Poor old Celestine was hopeless at running a theocratic state and was kept a virtual prisoner by the King of Naples and the crafty cardinals. He was illiterate, spoke no Latin, and would say yes to whatever was asked of him, sometimes granting the same benefice to multiple petitioners.

The craftiest of the cardinals, one Benedetto Caetani, undermined Celestine’s confidence even further. He went so far, it was said, to introduce a speaking tube into Celestine’s cell through which, in the small hours of the night, he would pretend to be the voice of God, telling the terrified pope to resign or face damnation. After five miserable months Celestine passed a decree allowing popes to resign and promptly invoked it, hoping to return to his hermitage.

Not everyone accepted his resignation, and in order to prevent him being set up as a rival, his successor as pope (Benedetto Caetani; now there’s a coincidence) who took the name Boniface VIII, made him an actual prisoner in a remote castle – which is not too different from how he had planned to live anyway – and before long he died.

Boniface could not have been more of a contrast to Celestine. He was a typical medieval “bad pope” – not as outright evil or debauched as some, but not particularly interested in spiritual matters, and very interested indeed in extending his temporal power and empowering and enriching his family. He repealed all of Celestine’s decrees except for the one about papal resignations.

After Boniface in turn died, Celestine was canonised. This might seem to have been an apology from the church for the rotten way he had been treated, but in fact even that was political. Given that making him a saint was an implied criticism of Boniface, cardinals from the Caetani family and their allies all voted against canonisation, but were outvoted by their rivals, cardinals from the Colonna family and their allies.

Il Sentiero di Celestino

Before I could start my journey in the footsteps of Celestine, I drove up a narrow, steep and winding road to a village called Decontra, several hundred feet above Caramanico. This was a pretty little place in a spectacular setting, on the shoulder of a hill beneath some much higher mountains.

A single row of stone cottages lines the road. But what is pretty now would have been a harsh place to live until quite recently. It was the sort of place where the more prosperous people could aspire to build a two-storey house, so the animals and people could live in different rooms.

Having found somewhere to park, as I was loading myself up for the walk I saw someone whom I took to be another hardy trekkista approaching across a field. Then I noticed that he was accompanied by a large herd of sheep – no, goats – no, sheep and goats. And he was an elderly she.

She had three dogs with her but only one seemed to be making any contribution; the other two were more interested in playing, saying hello to tourists and so forth. So the sheep and goats were heading in all directions and it took the lady quite a bit of running around, yelling and hitting any nearby animal with her stick, to get them all going in the same direction.

Which she eventually did, and off they all went in search, literally, of greener pastures. I felt that I had been given a glimpse of the past, or to be more accurate, a glimpse of something that would shortly become part of the past. I mean, good luck getting anyone under seventy to take that on as a profession.

The Valle Giumentina

To get to the eremo was going to be a couple of hours’ walk through an area called the Valle Giumentina, which is a wide valley sloping down from the high Apennines towards the distant Adriatic. It is shown on Google Maps as a “neolithic archaeological site”, and sure enough it is covered with little piles of stones. At one side of the valley some entrepreneur has recreated a “paleolithic village” of little round stone huts – it wasn’t open during the week, but even from a distance it was rather reminiscent of The Flintstones.

Paleolithic and neolithic things have indeed been found here, and it seems that in prehistoric times the locals used the valley for transhumance, and built little stone huts (called tholoi) in which to store things, and in which to turn the milk from their flocks into cheese. But here’s the problem: so did every subsequent generation until after the Second World War. So was that pile of stones the remains of a hut from 1000 BC, or of one from 1950? I resolved to visit the archaeological museum in Chieti the next day to find out.

The Eremo di San Bartolomeo in Legio

On the edge of the Valle Giumentina the limestone has been eroded into a deep ravine, on the side of which there is a natural stone platform under an overhanging rock, and on that platform is a little chapel and an adjoining cell. According to a plaque at the site, it had already been built and had then fallen into ruin when Celestine, or Pietro as he still was, rebuilt it and moved in.

There are two ways to get to the hermitage, and both seem to be equally arduous. As it turned out I had chosen the better route for photography, as it approached from the other side of the valley, giving much better views. The other route approaches from above, and you would not be able to see the place until you got to it. Even from my side of the ravine it was a bit hard to make out at first – in the photograph below it is at the lower left.

It was a bit of a scramble down, and a tiring climb back up, but worth it for the photographs.

Poor old Celestine has been remembered though; the walking trail which links several of these barely-accessible hermitages is the Sentiero di Celestino. Of course, the hardy trekkisti with bulging calf muscles, Ray-Ban sunglasses and carbon fibre walking sticks might not look much like the wild-eyed, half-starved hermit who became history’s most reluctant pope, but there you are. In addition I note that there is a “Bar Celestino” in Sulmona, to which no doubt a modern Celestine could come down from the mountain if he felt like an Aperol Spritz.

Chieti

The next day I did indeed drive to Chieti – a handsome town on a hill between the mountains and the sea – and visited the archaeological museum. It did not enlighten me regarding the Valle Giumentina – the attendant I consulted was knowledgeable about the rules on photography in the museum, but had never heard of the Valle Giumentina. I’ve since found some academic papers online which variously date human habitation in the Valle to the Paleolithic and indeed late Pleistocene eras. The visit to the museum was by no means a waste of time, as there was a lot of information about the various pre-Roman clans and tribes in the area, and I did get to see the slightly-famous “Warrior of Capestrano”, a grave statue from the 6th Century BC. With his wide-brimmed helmet and the diagonal shoulder straps holding his breastplate on, he looks a bit Mexican.

Further Reading

There is plenty about Celestine V online, but one of the more satisfying sources is The Popes by John Julius Norwich (London 2011). Celestine and Boniface are dealt with starting on page 189.