Just outside Mantua is the Palazzo Te, built by the first Duke of Mantua as a pavilion for leisure, and love.

When I first heard of the Palazzo Te (I think it might have been on TV) I came away with the impression that the name actually meant “Palace of Tea”, implying its use as a retreat for graceful pursuits. Only later did it occur to me that there were two problems with this interpretation. One is that the Italian for tea is not te but tè (with the accent). A more substantial objection is that the palace predates the introduction of tea into Europe by several decades at least.

A more plausible etymology is that the land on which it was built was an island in the swampy land around the River Mincio. The island was called Tejeto, shortened to Te. I gather that even this explanation lacks corroboration, but I think we can all agree that it has nothing to do with tea.

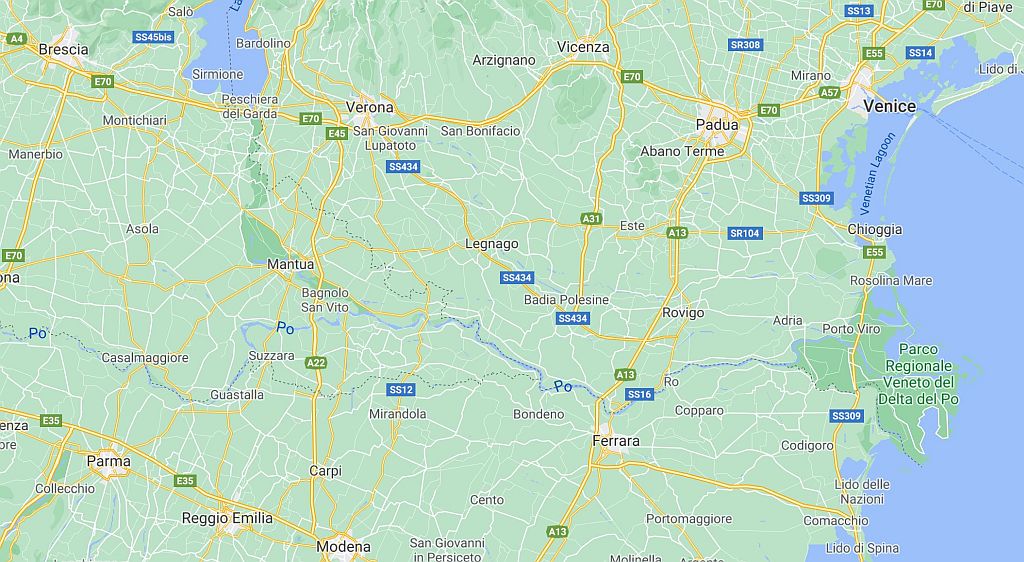

After our visit to the Ducal Palace, we made a separate trip into Mantua to see the Palazzo Te, as it is a fair way south of the centre of the city. As it transpired the day of our visit was very hot and we were glad of the opportunity to park close by. The map below shows the location of Palazzo Te.

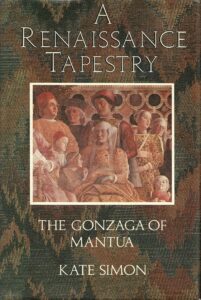

We met the ruling family of Mantua, the Gonzagas, in my post “Mantua – Grumpy Old Artist, Charming Painting” which was mostly about the famous paintings by Mantegna on the walls and ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi in the Ducal Palace.

Federico Gonzaga

The head of the Gonzaga Family at the time they employed Mantegna was Ludovico III, the second Marquis. His great-grandson was Federico II, the fifth Marquis and, from 1530, the first Duke of Mantua, and it was Federico that built Palazzo Te. Federico’s mother was the formidable Isabella d’Este of Ferrara, who was a noted art collector and who was no doubt responsible for that part of his education.

Although what comes later in this article might suggest that Federico was no more than a dissolute lover of pleasure, he was a soldier and an active military player in the campaigns of Popes and Emperors.

Although Federico came three generations after Ludovico, he assumed the title only 22 years after Ludovico’s death; it seems that most of the male Gonzagas were not long-lived. That may have had something to do with the malarial environment of Mantua, but in fact both Federico and his father Francesco died of syphilis, only recently introduced from America but already spreading rapidly.

Perhaps not unrelated to the syphilis, the male Gonzagas were highly philoprogenitive, indeed priapic. Ludovico had had ten legitimate surviving children, his son and grandson six each, and Federico had five. And that was just with their wives.

Federico had several mistresses in his youth, but the one to whom he became attached for most of his life was a lady called Isabella Boschetti, known as “La Bella Boschetta”. At a time when rulers’ wives were chosen for dynastic and diplomatic reasons, it was quite common for them to take mistresses as well; not just casual affairs but long-term attachments which, as in Federico’s case, might pre-date their marriages. Frequently the children of such relationships were raised in the father’s household alongside their legitimate children, which was fairly sporting of the real wives, to whom custom did not extend the same latitude.

Federico had two children by Isabella, a boy who went on to become a state councillor in Mantua, and a girl who married a distant relative of Federico’s.

The picture below, referred to boringly by art historians as Portrait of a Lady with a Mirror, is also by Titian and is thought to be of Isabella Boschetti.

The New Palace

Some time around 1524 Federico decided to build a new palace, which would be both a separate household for him and Isabella, and a pleasant retreat outside the city. The site was still surrounded by water, and the suburban buildings which now surround the Palazzo Te and its grounds all look to have been built in the last century or so, which suggests that the area around was reclaimed relatively recently.

The artist and architect that Federico commissioned to design, and decorate the Palazzo Te was Giulio Romano (born Giulio Pippi in Rome, so when he left there he was called “Giulio the Roman” in that imaginative way they had in those days). In his youth in Rome he was apprenticed to Raphael and worked with him both in the Vatican and the Villa Farnesina, and took over those projects after Raphael’s early death.

Giulio’s fame thus grew, and in due course Federico persuaded him to come to Mantua as court artist. In those days there was considerable overlap between artists and architects, so it was not unusual for Giulio to be awarded the brief for the Palazzo Te. His work lacks the finesse of his predecessor Mantegna and his master Raphael, but there is no doubt that when it came to a big project like the Palazzo Te, he was up for it.

The Palazzo is in what is known as the late-Renaissance “mannerist” architectural style – where the earlier attempts to replicate classical styles had become a bit more like “riffing on a classical theme”. As you can see in the photograph below, the various columns, friezes and architraves perform no load-bearing function – they are just decorations.

The Palazzo Te isn’t quite as over-the-top as the Cavallerizza in the Ducal Palace from a generation later, which looks a bit as if the architect was taking mind-altering substances. A photograph of the Cavallerizza is in my earlier post on Mantua.

The Interior

Inside is where the Palazzo Te starts to get really memorable. There are a couple of very large frescoes which illustrate the sort of purposes that Federico had in mind for the place. HONEST IDLENESS AFTER LABOUR reads one inscription, and since such honest idleness seems to involve Bacchus, wine, naked women and priapic satyrs, one gets the general idea.

In my earlier post on Mantua I mentioned that the place was famous for breeding warhorses – a lucrative state business of which Henry VIII of England was one of many customers. No surprise then to see several of them celebrated in the frescoes in the Sala dei Cavalli.

Many of the other frescoes are of classical and biblical themes, which despite their supposed propriety nonetheless manage to maintain the general air of lubriciousness. There is a room devoted to the story of Cupid and Psyche, and their illicit love, possibly a reference to Federico and Isabella.

In another room dedicated to Ovid’s Metamorphoses there is a giant picture of Polyphemus the Cyclops. To his left there is what I take to be Zeus seducing Persephone in the form of a dragon, and to his right, Daedalus helping Queen Pasiphae of Crete to disguise herself as a cow in order to have sex with a bull (of which union came the Minotaur). I assume that the two figures at the lower right might be Acis and Galatea.

And of course what could possibly be improper about a scene from scripture such as David and Bathsheba?

A typical feature of Renaissance palaces is the glorification of the owner. Sometimes this is explicit, such as in the slightly nauseating “Room of the Farnese Deeds” in the Villa Farnese at Caprarola. In general though these things tend to be done a bit more subtly, with famous scenes depicting classical virtues. The strong implication is that such virtues just happen to be exemplified by the boss, who is therefore a Decent Chap.

One such picture in the Palazzo Te depicts the occasion when Caesar was presented with letters and papers stolen from his rival Pompey. Despite the fact that they would have revealed the names of Pompey’s co-conspirators, Caesar refused to look at them because he did not wish to profit from underhand tactics, and instead angrily directed that they be burned unread.

This became an exemplary story about honour in warfare, with which of course Federico as a condottiere would wish to be associated. (I read somewhere that Caesar’s successors in antiquity would emulate him by ceremonially burning the papers of vanquished rivals – although not before making private copies for future reference!)

The Sala dei Giganti

The most memorable part of the interior decorations of the Palazzo Te is the Sala dei Giganti – the “Room of the Giants”. Giulio Romano’s fresco, which covers the entire surface of the walls and ceiling, illustrates the story of the giants who had attempted to build a tower reaching to Olympus, and who were destroyed by Zeus with thunderbolts.

While you couldn’t really describe the painting as refined, what Giulio lacked in elegance he certainly made up for in energy and scale. The grotesque and ugly giants are being crushed by the collapsing masonry, while the Olympian gods and demigods are looking down on them. In all the excitement some of the goddesses have managed to have wardrobe malfunctions.

The gods react in various ways to the giants, some in alarm, some in anger. Hera is standing beside Zeus, handing him more ammo in the form of thunderbolts.

I saw somewhere a suggestion that the cupola and circular balustrade at the very top of the picture is supposed to represent the Christian heaven, above the pagan one. This is a nice idea but there does not seem to be any obvious Christian iconography and no other sources mention it, so it can probably be disregarded.

Leaving the building, you find a small artificial grotto in a courtyard. Inside it is pleasant enough, but my principal memory of it is the motion sensor alarm which was too sensitive and went off before one got anywhere near the frescoes it was there to protect.

Magnificent as Federico’s reign might have appeared, his death in 1530 marked the start of the decline of Mantua. As I mentioned in my post on the life of Claudio Monteverdi, by the beginning of the 17th Century the Gonzagas were no longer a significant military force, were living well beyond their means, and were drifting into strategic and political irrelevance.

But the reigns of Ludovico and Federico bookended a glorious period in Italian history. While the Mantua that Federico ruled may have lacked the intellectual energy of Florence, the culture of Urbino or the sheer wealth of Venice, he certainly knew how to have a good time.

Note: I had originally thought of titling this piece “Crumpet, But no Tea”, but decided it would be both obscure to non-British English speakers, and also a bit juvenile for a respectable blog like this.