Capri – the home of a supposedly perverted emperor, a philanthropic Swedish doctor, and a fugitive Scottish-German aristocrat who became a great travel writer. I’ve been thinking for a while about how to try and pull these stories together, so here goes.

The photographs that illustrate this post were all taken on a visit to Capri in 2011, when I was still shooting film on a Hasselblad medium-format camera. We were staying in a village near Amalfi called Pogerola, which I described in my post on Amalfi and the Sorrentine Peninsula.

There is a fast ferry service from Amalfi to Capri. Actually it starts out from Salerno, and calls into Amalfi on the way. We got to the jetty early in the morning and while we waited for the ferry we breakfasted on coffee and pastries and I was able to take some nice photographs of Amalfi in the early light.

Shortly before the ferry arrived some buses deposited about a hundred German tourists who all piled on to the ferry as well. It was quite windy and the sea was a bit rough. As the ferry roared away from Amalfi a couple of genial-looking crew members strode up and down the aisles with lots of plastic bags sticking out of their pockets. The intended use for these became apparent as we hit the swell and before long various fellow-passengers started urgently requesting the bags to throw up into. Preferring to take my chances out in the weather I went upstairs to the open deck and before long Lou followed. We had pretty good views of the Sorrentine Peninsula as we went.

It had been a bit overcast in Amalfi but we arrived in Capri in bright sunshine. As expected the port was heaving with tourists, but it was better than the heaving tourists on the boat.

Tiberius (42 BC – 37 AD)

Arriving at the port of Capri, we headed up to the main town. Seeing the length of the queue for the funicular up to Capri, we decided to walk the kilometre or so up the hill.

At this point I should introduce the first of our three historical characters: Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus, the second emperor or Rome, who reigned from AD14 to AD37. Tiberius has been dealt a doubly bad hand by history, getting stuck with a job he didn’t want, then being libelled by ancient historians for his troubles. The stepson and adopted son of the first emperor Augustus, he was manoeuvred into the succession by Augustus’s second wife, Tiberius’s mother Livia, who, as I discussed here, was probably not as bad as she has been portrayed, but a fairly forceful character nonetheless.

What is not in doubt is that Tiberius was an able administrator, a successful general, a competent lawyer, and – apparently – a reluctant emperor. Happily married to a woman he loved, he was forced by Augustus to divorce her and to marry Augustus’s own daughter Julia (now Tiberius’s step-sister) who proved to be unfaithful and promiscuous. Humiliated by this, forbidden to meet his beloved former wife and treated with hostility by the senatorial class, Tiberius announced his retirement from public life to the Greek island of Rhodes. But this deprived Augustus of an obvious successor, and Tiberius came under considerable pressure to return to Rome.

Eventually he did return, Augustus died (probably not poisoned by Livia, whatever Robert Graves may have written in I Claudius), and Tiberius became emperor. As only the second-ever emperor of Rome, Tiberius’s constitutional position and the legitimacy of the imperial office were still rather vague. Tiberius’s own view of the proper form of government for Rome is unknown, but he declined several of the traditional titular honours that Augustus had held. Unfortunately the Senate and the aristocratic class chose to interpret this not as a sign of humility, but of arrogance and hypocrisy.

Before long Tiberius had had enough of all this, and left Rome to live the rest of his life on Capri, maintaining overall control but leaving the day-to-day administration in the hands of the Praetorian Prefect Sejanus (who eventually showed imperial ambitions of his own and came to a sticky end). The conventional explanation for Tiberius’s departure is that he was distrustful of the Senate and fearful of assassination, which is plausible enough. That being said, I have seen an article suggesting that he was actually trying to get away from his mother Livia’s constant interference, which is also plausible (a view shared by Norman Douglas; see below).

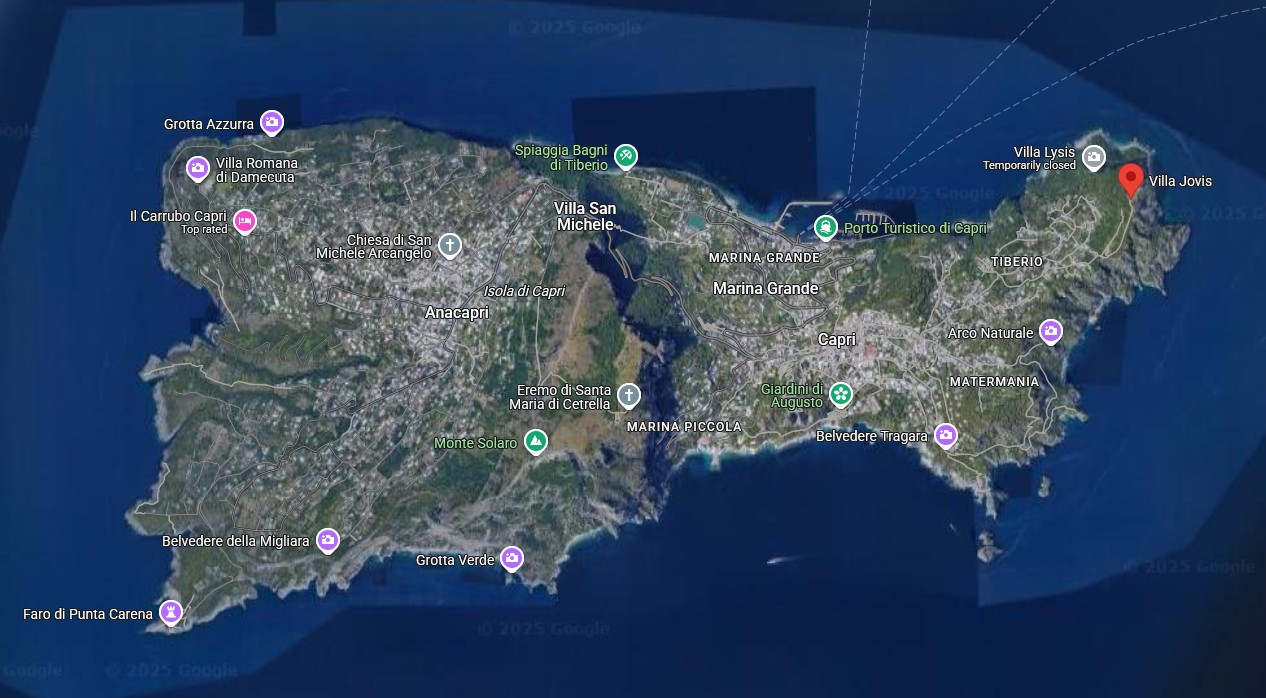

On Capri Tiberius built several villas, but mainly lived in a luxurious palace called the Villa Jovis (Villa of Jupiter). This is located at the north-eastern corner of the island with a view back to the mainland which includes Vesuvius and the tip of the Sorrentine peninsula.

The stories that have come down to us about Tiberius’s supposed depravities on Capri are lurid, and include employing young boys to swim up to him underwater to perform various intimate acts, and forced sex with otherwise virtuous women and young men, sometimes resulting in their deaths at their own hands, or on Tiberius’s orders.

What are we to make of this? It may all have been true, but I can think of two reasons for scepticism. One is that this behaviour does seem completely out of character with what we know of Tiberius before he retired to Capri. A second is that we must always remember that due to the loss of so many ancient manuscripts, we actually do not have very many historical sources for this period, and what we know about Tiberius comes mostly from only two historians – Tacitus and Suetonius, who have therefore been enormously influential in shaping the perceptions of later ages. Neither historian was a fan of the Julio-Claudian family – both were players in the politics of their own times, and had their own factional prejudices and axes to grind. Moreover they were writing under a subsequent imperial dynasty, and like Shakespeare with the Tudors it would have been in their interests implicitly to praise the virtues of the present regime by inventing stories of the wickedness of its predecessors. Tiberius, in other words, has had the same sort of bum rap as Richard III, and for similar reasons.

The most eloquent and erudite defence of Tiberius that I have seen comes from his fellow Capri resident Norman Douglas, of whom I will say more below, but while the salacious tales of Tiberius’s debaucheries have been debunked by modern scholars, nothing sells like scandal. So you will unfortunately find them repeated in much tourist literature, and no doubt in the spiels of the guides leading their troops of foreign visitors around.

Axel Munthe (1857 – 1949)

But next, to a Swedish doctor and writer who lived an eventful life, became a British citizen, and wrote a famous autobiography called The Story of San Michele. The San Michele in question is a villa, high on the northern cliffs of Capri, which Munthe purchased as a ruin, restored, and lived in for many years.

In the photograph above, you can see the scar in the side of the distant cliff where a narrow road climbs up from the town of Capri to the island’s second town, Anacapri. Just on the edge of the cliff, above the road, you can see a little white dot of a building with some trees behind it. That is San Michele, or one of its near neighbours.

To get to Anacapri from the town of Capri we caught a little local bus. The Capri residents, on their way home with their groceries, rushed on first and took all the seats, leaving us tourists to stand and hang onto the straps. This, while less comfortable, made the journey very memorable. If you look again at the photograph above, you will see that the road hugs a nearly sheer cliff face. The bus driver, like many Italians a secret racing driver, hurled us up that road, with – for those of us standing up on the right-hand side of the vehicle – near-vertical views down to the sea as we screeched round the bends. People have paid a lot of money for rides that are less scary than this was. While the standing tourists gasped in terror, the seated locals chatted amiably or read their newspapers.

From Anacapri we continued our ascent by taking the seggiovia, or chairlift, to the top of Monte Solaro, from which we enjoyed a magnificent view – from the Sorrentine peninsula to the east, past Vesuvius and the Bay of Naples to the islands of Ischia and Procida. Here are some photographs of that view, after which we will return to the subject of Axel Munthe.

Munthe attended medical school at Uppsala University in Sweden, then continued his medical studies in Paris. It was during his student years that he visited Capri, and like us made the ascent to Anacapri. There he found an old peasant’s cottage next to a ruined chapel dedicated to San Michele. He immediately formed the ambition to return one day, buy both buildings, and rebuild them into a villa in which he would live. And looking at the pictures above, who could blame him?

The Villa San Michele is quite a long way from Tiberius’s Villa Jovis, as you can see on the map above, but there were Roman remains on the site, and Munthe was quite convinced that these were the remains of a villa of Tiberius. Given that Tiberius apparently had several villas on Capri, this is by no means unlikely, particularly as the view would have been as spectacular in the First Century as it was in the Nineteenth .

Munthe’s medical career combined lucrative practising to high society and the wealthy (including the Swedish Royal Family), and philanthropic care to the poor without charge. In due course he became personal physician to, and a close friend of, Queen Victoria of Sweden, who would later spend several months each year on Capri on his advice.

He was a regular volunteer during natural disasters, and it was shortly after helping out during a cholera epidemic in Naples in 1884 that he finally was able to buy the Villa San Michele, and commence the long restoration. The workmen on the site were as convinced as he was that they were excavating one of Tiberius’s villas; when one of them uncovered an old clay tobacco pipe, he presented it to Munthe saying “look, Tiberius’s pipe!”. To help defray the costs of the restoration, Munthe opened a clinic in Rome.

After the 1908 earthquake that destroyed Messina in Sicily, Munthe went to assist and his account of the earthquake’s aftermath in The Story of San Michele is quite horrific.

Munthe married a wealthy Englishwoman and during the First World War he became a British citizen and served in the Ambulance Corps. Their son Malcolm became a member of the Special Operations Executive and a clandestine operative behind German lines in Norway in the Second World War.

I have to admit that I am not sure quite what to make of Axel Munthe. The first time I read The Story of San Michele, many years ago, I came away with the impression that it was all rather self-serving and self-glorifying, with many rather tendentious episodes demonstrating his virtue. It seems I am not the only one to think so. The part of the book that deals with his time in Paris and the pioneering French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, which ends up with his “rescuing” one of Charcot’s clinical hypnosis subjects, has been comprehensively debunked.

That being said, it is possible that Munthe himself was alive to this criticism. On re-reading the book some years later in a different edition, I paid a bit more attention to the preface, written in 1928, in which the aged (English) Munthe seems to confront an imaginary version of his youthful (Swedish) former self. It is worth quoting at length.

Unfortunately I have been writing The Story of San Michele under peculiar difficulties. I was interrupted at the very beginning by an unexpected visitor who sat down opposite me at the writing-table and began to talk about himself and his own affairs in the most erratic manner, as if all this nonsense could interest anybody but himself. There was something very irritating and un-English in the way he kept on relating his various adventures where he always seemed to turn out to have been the hero – too much Ego in your Cosmos, young man, thought I… Medicine seemed to be his special hobby, he said he was a nerve specialist and boasted of being a pupil of Charcot’s as they all do… At last I told him to leave me alone and let me go on with my Story of San Michele and my description of my precious marble fragments from the villa of Tiberius.

“Poor old man,” said the young fellow with his patronizing smile, “you are talking through your hat! I fear you cannot even read your own handwriting! It is not about San Michele and your precious marble fragments from the villa of Tiberius you have been writing the whole time, it is only some fragments of clay from your own broken life that you have brought to light.”

Norman Douglas (1868 – 1952)

Norman Douglas was born in Austria to a Scottish father and a German mother, both aristocrats. Educated in England and Germany, he joined the British Diplomatic Corps and was posted to St Petersburg, but in what was to become a pattern, his diplomatic career came to an early close after a series of scandalous affairs with Russian ladies, one of whom he abandoned when she was pregnant.

He married a cousin, with whom he moved to Italy and had two children. Soon afterwards however the marriage ended in divorce, based – perhaps surprisingly – not on his infidelity but on hers. After that Douglas’s sexual tastes tended towards young people, both boys and girls, which would have got him into very serious trouble today. As it was, in both 1916 and 1917 he was charged in London with indecent behaviour with underage boys and, on the second occasion he skipped bail and moved to Capri, these being the days before Interpol warrants. In 1937 he had to leave Florence in a hurry, this time over allegations involving a young girl.

D.H. Lawrence based the character James Argyle in Aaron’s Rod on Douglas, and it has been claimed that he was the model for Humbert Humbert in Nabokov’s Lolita. Given the literary circles in which he moved, it is hard not to imagine Douglas as the model for a few rascally characters in contemporary literature who are regularly getting into trouble and having to make a quick exit. One thinks of Evelyn Waugh’s Captain Grimes and Lawrence Durrell’s Scobie. But as with Caravaggio and Bernini one should try and consider the artist’s work separately from his crimes, so let us do just that.

Based mostly on Capri for the rest of his life (he spent the Second World War in London where presumably the bail-jumping of three decades earlier was overlooked), Norman supported himself on a modest family income, and writing: mostly novels and travel books. His travel books would not be to everyone’s taste – as guidebooks they would be useless, and his narrative meanders about with frequent historical and literary diversions which make no allowance for the reader’s own level of knowledge. One must follow along as best one can, and occasionally get a bit exasperated.

But if you enjoy being in an ancient landscape and reflecting on the palimpsest of history and literature that lies behind the views and the tourist attractions, then Douglas becomes an engaging and erudite companion. One can imagine accompanying him along some mountain track in Capri while he waves his walking stick about pointing out where some episode from The Odyssey is supposed to have occurred, or the location of one of Tiberius’s villas, followed by a forensic critical analysis of Tacitus and Suetonius. It would be great fun, although you might not bring the children along.

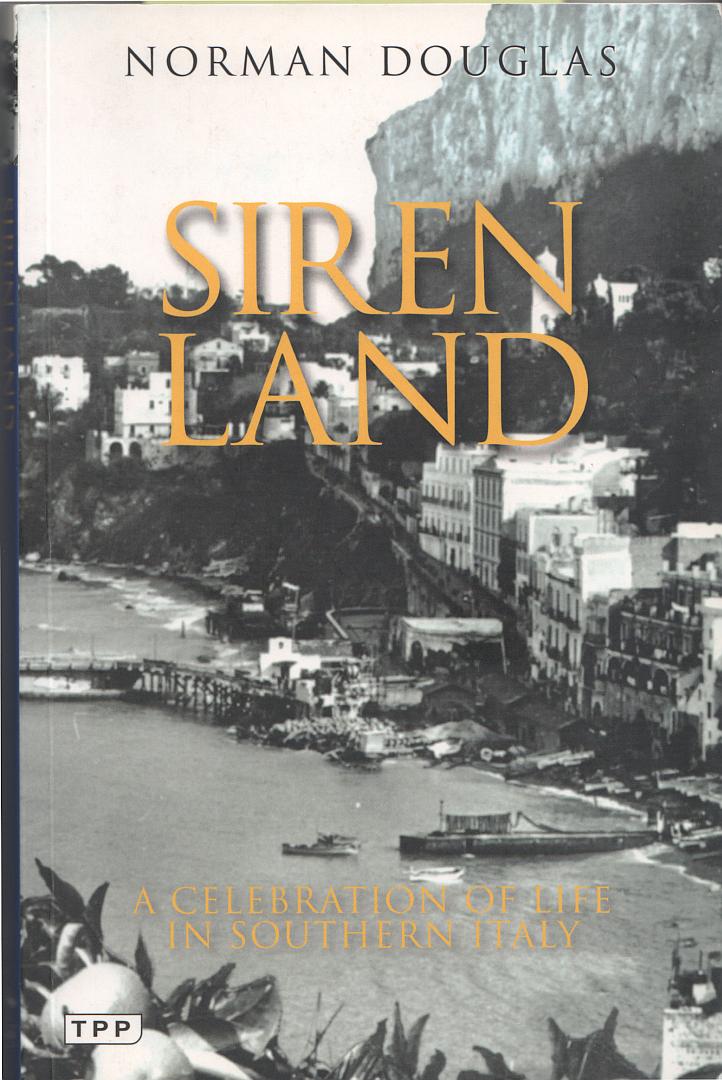

Of his many books, one of the first – Siren Land – is about Capri and the Sorrentine peninsula, more or less. That was written in 1911, and in 1917 he followed it with a novel – South Wind – in which the setting is a fictional version of Capri and various expatriates appear in thin disguise. Its theme of the brittleness of conventional morality was considered quite scandalous at the time.

I mentioned earlier that Norman Douglas mounts an eloquent and erudite defence of Tiberius. In other words, a known 20th-Century pederast defending a 1st-Century emperor against charges which included pederasty. I suppose that makes him some sort of expert witness. Anyway, this is from Siren Land:

After a youth of exemplary virtue, and half a century more of public life, during which the manners and morals of Tiberius were an honour to his age, he retired in his sixty-ninth year to the island of Capri, in order at last to be able to indulge his latent proclivities for cruelty and lust. So, at least, the wisest of us believed for twenty centuries. We have all heard of the reformed rake; Tiberius was the reverse: from being an Admirable Crichton, he became the prototype of the Marquis de Sade. But it is needless to go into this res adiudicata; historians like Duruy, Merivale, and Ferrero, however much they disagree upon other questions, are at one upon this: that no scholar of today, with a reputation to lose, should stake it upon the veracity of Tacitus and Suetonius…

And on he goes in this vein, for several pages, in which he questions Tacitus’s mental health, and attributes the historian’s extreme adherence to the aristocratic anti-Tiberius faction to the fact that Tacitus was a social climber and dreadful snob, trying too hard to fit in. He wonders whether posterity was the more ready to accept these calumnies due to the fact that it was during Tiberius’s reign that Christ was crucified, despite the fact that Tiberius would not personally have had anything to do with a local public order matter in Palestine.

While not going so far as to call Tiberius a closet republican, Douglas suggests that Tiberius “attempted the experiment of constitutional rule, interfering as little as possible in the machinery of the state, while reserving to himself the last word upon all graver matters.“

Having thus made Tiberius the very model of a modern constitutional monarch, Douglas then compares Tiberius very favourably with actual “modern” (ie 1911) monarchs:

The idea of retiring from the cares of government may seem absurd to us. But we must consider the kind of work which confronted Tiberius. Modern sovereigns, whose most violent physical exercise takes the form of shooting tame pheasants or leading a drowsy state-ball quadrille, would be killed outright by a single one of his many campaigns: the economic problems with which he grappled day after day would permanently liquefy their brains.

And off he goes in yet another direction, but always – eventually – bringing us back to the sun-drenched coasts of southern Italy.

Douglas ends his discussion of Tiberius with the hope that science will one day allow us to read the carbonised scrolls of Herculaneum and find among them some more objective histories of the early imperial era. Now, more than a hundred years after he wrote that, we seem very close indeed to doing just that. I hope I live long enough to see it.

__________________________

Three fascinating characters, each very different, but all of whom trod the steep hillsides of Capri and gazed into the blue expanse of the Bay of Naples. How I would like to have talked to them. Was Tiberius the evil pervert described by Suetonius, or the serious and responsible Roman citizen that he seems to have been in his early life? Axel Munthe’s conversation would have been expansive and informative, although some of his stories about himself might need to be taken with a grain of salt.

But I have no doubt that it would be Norman Douglas who would have been the most erudite and (albeit somewhat scandalously) entertaining.