A return visit to Palermo gave me the opportunity to take photographs I had been unable to take before, and reflect more on the extraordinary legacy of Norman Sicily.

My post on Norman Sicily was written back in 2019, but illustrated with photographs I took on a visit in 2012. Recently (July 2024) we revisited Sicily, and I was able to take some more photographs. Rather than rewrite the original article and replace the images, I have decided to write a supplementary article, but if you are interested in the fascinating story of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, I recommend that you read the original article for more historical background.

The Photography

Those 2012 photographs were all taken on slow (ISO 50) Fujichrome Velvia film, using either a Hasselblad 501 C/M medium format camera or a Horseman 45FA large-format camera. For indoor shots I used the Hasselblad, but Velvia is a film meant for outdoor landscape photography, and the colour casts from low-light indoor photography were quite strong. The slow speed of the film also required exposures too long for hand-holding, which meant that I was restricted to situations where I could place the camera on a hard surface or brace it against something like a pillar (tripods are of course not allowed indoors).

This time I had my Fujifilm GFX-50R with me, which had several advantages. With indoor photography using this camera, I generally set the aperture and exposure manually, and leave the ISO on automatic (the GFX-50R goes up to ISO 12800). High ISOs mean greater digital “noise” (like the grain in fast film) but the large sensor on the 50R means the noise is less obvious. When necessary I then used a program called Topaz DeNoise AI to reduce the noise further. I was also able to use digital perspective correction to reduce the “leaning back” effect when things are photographed from below.

Cefalù

After taking our car across the strait to Messina on the ferry, our first stop was Cefalù, on the north coast. This town is spectacularly situated on a headland below a giant rock, and it was here, in 1131, that the Norman King Roger II commissioned a cathedral in which he planned to be buried. I have not come across any explanation as to why he chose Cefalù, but in the event his son William I decided to bury Roger in Palermo Cathedral, so he did not get his wish. It would have been a beautiful and peaceful place though.

Beautiful Cefalù still is, although you could not have described it as peaceful when we visited. The throngs of people were not there to soak up the glories of Norman-Sicilian architecture; these days Cefalù is a beach resort, and they were there to soak up the sun. We were there for the Duomo, however, so proceeded there through the crowded streets. It is a very beautiful building, with – to my untutored eye – a fascinating mixture of architectural styles. The twin campanili have Romanesque double-arched windows, but the front portico is a mixture. In the centre is a curved Romanesque arch, with pointy curved arches either side which are not European Gothic but Fatimid Arab. I suspect the decoration above the portico is also inspired by Arab architecture. Being surrounded by palm trees gives it all an exotic feel as well.

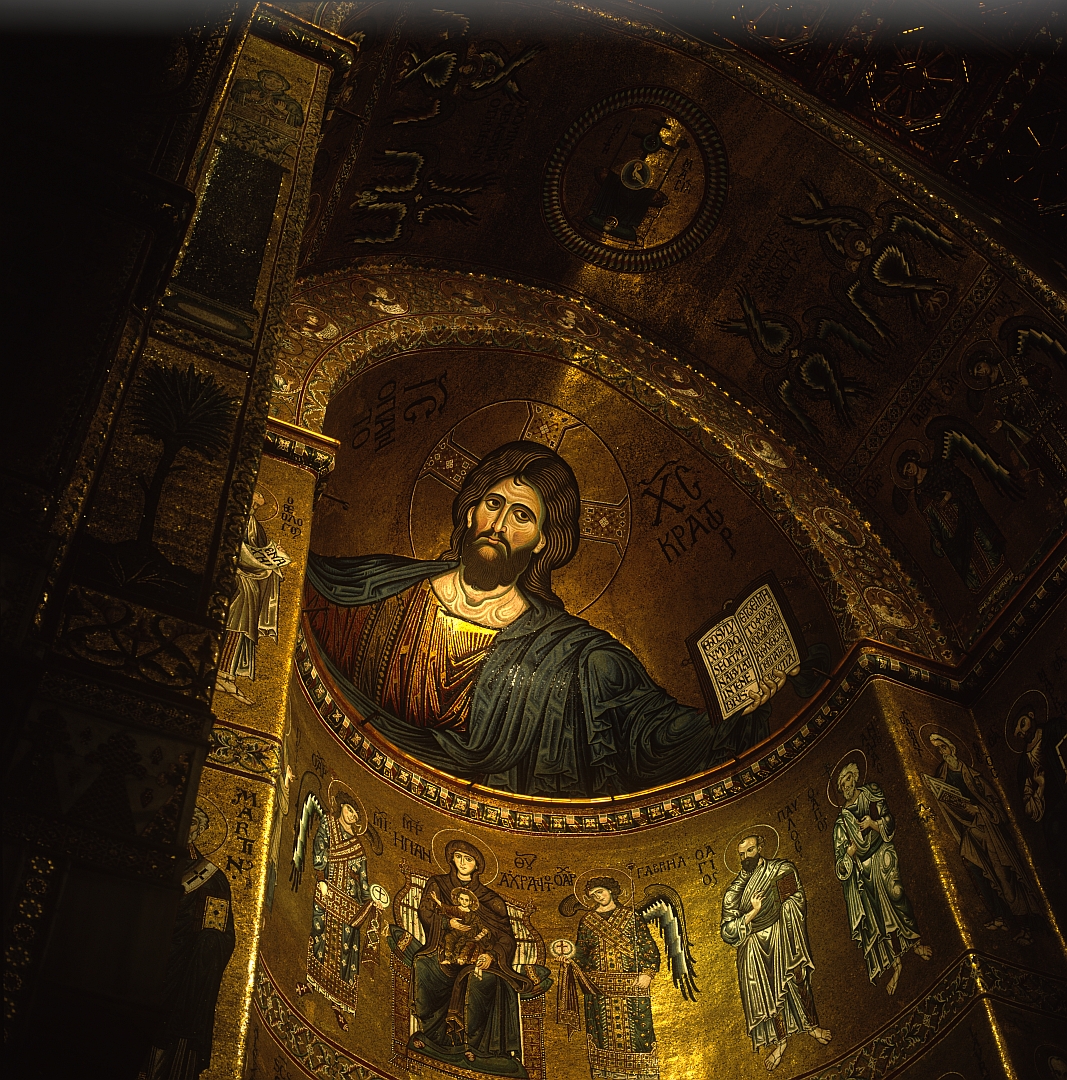

We arrived just as a wedding was about to start, but I was still able to grab some photographs, in particular some of the huge Christos Pantokrator mosaic in the apse. This was executed by Greek craftsmen brought from Constantinople, but it strikes me as not having quite the remoteness that one sees in Byzantine religious art (where iconoclasm was still a memory, and realism not encouraged). Instead there seems to be something of the western preoccupation with the humanity of Christ. And as ever I was struck by how much more sophisticated it is than most of the art that was being produced elsewhere in Europe at the time. A couple of weeks later we were in the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia, looking at works from one or two centuries later, and there was no comparison. The first depictions of emotion in post-classical western art are attributed to Giotto in the 13th-14th Centuries, but this came first by a long way.

Monreale

From Cefalù we continued our journey to Palermo, or to be more accurate, to Monreale. This town sits on a hill above the Conca d’Oro – Palermo’s coastal plain. Staying there would provide us with a bit of relief from the July heat at sea level, and also from driving in Palermo’s traffic.

What makes Monreale famous is not the climate or the traffic though, but its cathedral. The duomo was commissioned in the late 1100s by Roger II’s grandson William II (“The Good”), and represents probably the high point of this wonderful Norman-Sicilian syncretic tradition.

In the photograph above the sort-of Romanesque and sort-of Gothic arches are in fact, like those on the portico at Cefalù, very much Fatimid Arab.

The best part of the Monreale Duomo is the magnificent Christos Pantokrator in the apse, even greater in my opinion than the one in Cefalù. Unfortunately this year the apse mosaics are undergoing restoration and are all behind scaffolding. There is a large print of the mosaics hung on the front of the scaffolding, but it’s nothing like the real thing. So that was a bit disappointing; instead here is a picture I took in 2012.

Another disappointment was not being able to take a close-up photo with a long lens of the mosaic showing William II presenting the church to the Virgin Mary. Here is a version from 2012 – the mosaic would either have been done while William was alive, or shortly after his death.

To give you an idea of the sort of effect I was hoping for, here is a picture of Noah and his ark from our recent visit to Monreale. I zoomed in close, and then used software perspective correction to compensate for the fact that I was taking from below. I had really wanted a picture of the William II mosaic to which I could give a similar treatment. Oh well.

The Benedictine Cloisters

Thankfully not undergoing renovation was the adjoining Benedictine cloister, dating from around 1200. This is a lovely peaceful place, especially if you manage to get there between tour groups.

It’s another wonderful stylistic synthesis: an authentic Benedictine quadrangular plan, Arab arches, Greek mosaic patterns on the columns, Norman-French carvings on the capitals. And the overall exotic flavour is enhanced by the palm trees.

The Cappella Palatina

We then headed down into Palermo, with our destination the complex known as the Royal Palace, or the Palace of the Normans (Palazzo Reale or Palazzo dei Normanni). It also hosts the modern Sicilian Regional Assembly. From the outside the effect is all rather 18th-Century, due to the various accretions it has received over the years, but the core of the building started as a Norman castle built by Count Roger I shortly after the conquest of Sicily in 1072, and over time more was added, most notably the Cappella Palatina (Palace Chapel) in 1132, by Roger’s son Roger II. (Roger II was recognised as King of Sicily by the Pope in return for some military assistance).

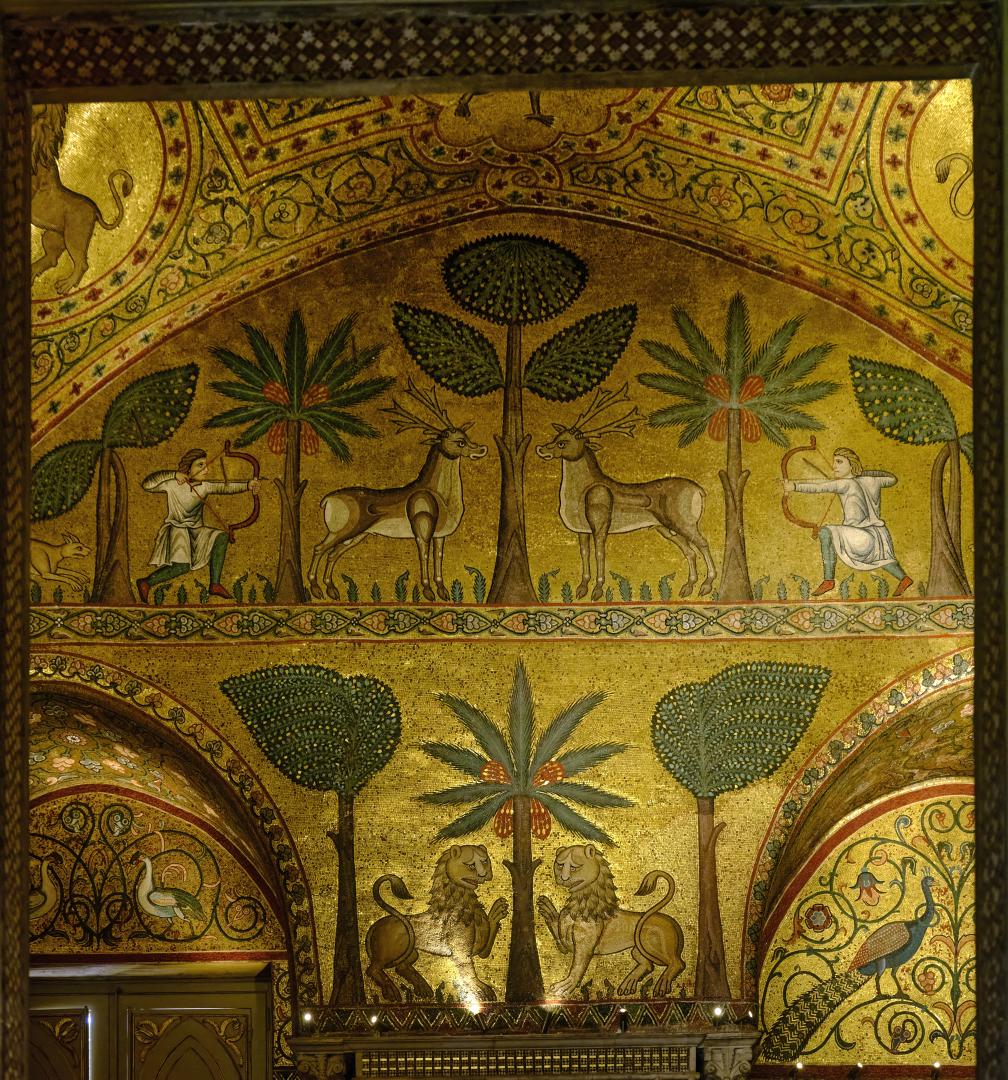

Like the cathedrals at Cefalù and at Monreale, the Cappella Palatina shows influences from all the Sicilian cultures. Like the others, there is an overall Norman plan, Latin-themed illustrations executed by Greek mosaic craftsmen, and Arab-inspired arches. There is also an extraordinary Arabic wooden muqarnas ceiling, inscribed with Koranic texts.

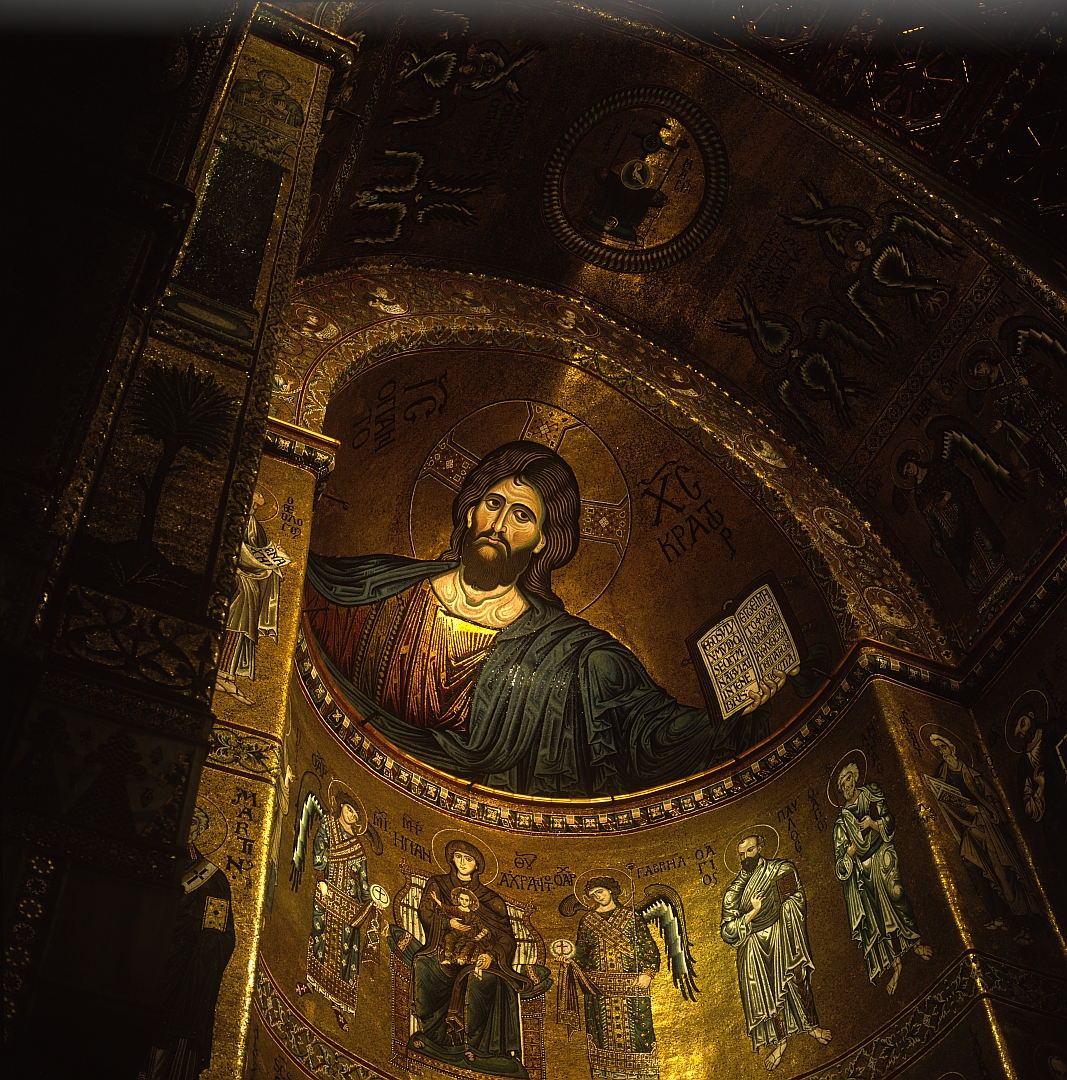

Outside there is a stone inscribed with blessings in Latin, Greek and Arabic. No more explicit statement could have been made of Roger’s intent that there should be peace between the various Sicilian peoples.

The Sala di Ruggero

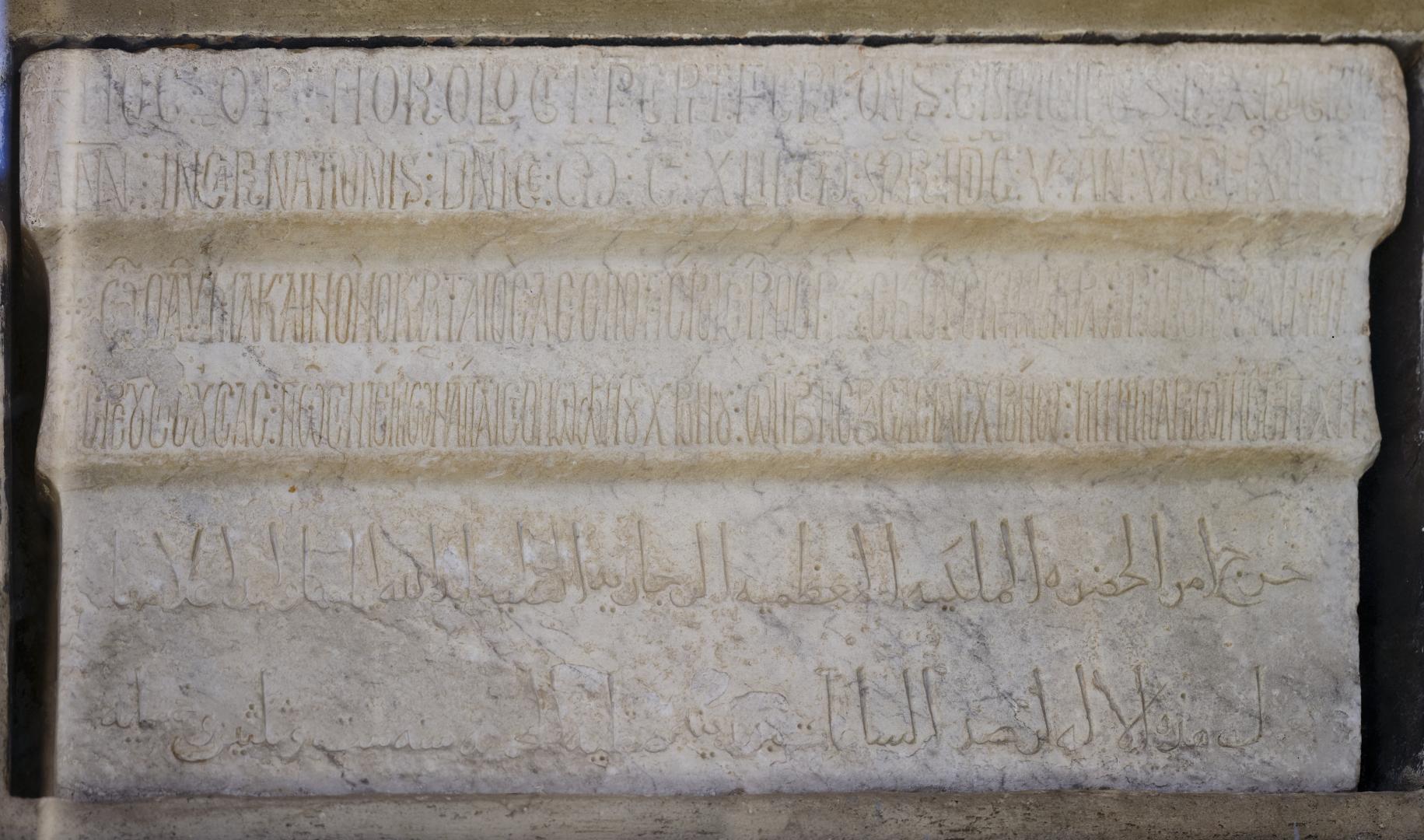

Earlier disappointments quickly faded when we headed upstairs from the Cappella Palatina to the so-called Sala di Ruggero (Roger’s Room). When we last visited in 2012 there was a ban on photography here, which unlike most of the other visitors, I had actually observed. In 2024, to my delight, there was no longer any such ban so I thoroughly enjoyed myself.

This room, presumably a reception room rather than private quarters (some describe it as a bedroom though), is beautiful by any standard but extraordinary by the standard of the 12th Century.

The fierce-looking leopards in the picture above have become a somewhat common sight in Sicily as they have been adopted as the logo of a chain of expensive souvenir shops. I suppose they are out of copyright by now.

The Sala di Ruggero leads off a central “wind tower” (another Arab architectural feature). The idea of a wind tower is that as the upper part heats up in the sun, the hot air rises and escapes through the windows at the top, thus creating an updraft which draws cooler air in from below. It seemed that the upper windows were not open this time, but they had been on our previous visit and it was quite effective then.

The Cathedral

We did not have time to do much more than photograph the outside of the cathedral as we passed, so there will be something to do on our next visit. The cathedral was started in 1185 by an archbishop of Palermo whose name has been variously mangled as Walter Ophamil and Gualtiero Offamiglia, but was originally Walter of the Mill; he was an Englishman.

It was built over, and incorporates, the remains of an earlier Byzantine basilica which had been turned into a mosque after the Arab conquest. In the late 18th Century someone added various neoclassical features, including a lantern and dome. It is this dome, which looks more or less like those over every other baroque church in Sicily, which fooled me the first time I saw it. It draws the eye and, used as I am to making sweeping judgements, it created an immediate impression of baroque architecture and I rather lost interest. But look closer. Even better, use your thumb or your hand (depending on how you are viewing this) to cover the dome.

I find that by blocking out the dome in this way, the other features – the pointy crenellations, the Arab-style arches and so forth – assume greater prominence, and suddenly the building looks much more eastern and exotic.

The End of the Hautevilles

It was all too good to last. The de Hauteville line died out and, through William II’s Aunt Constance, Sicily passed to her son, the Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen. Frederick was every bit as tolerant as Roger had been, and a polymath who deserved his nickname of “Stupor Mundi“, the wonder of the world. But his tolerance of Arabs and Jews infuriated the Popes, and in due course they engineered the accession of the French House of Anjou to the throne of Sicily.

I find it strange and a bit sad that modern Sicilians look back on the Norman era as a golden age, especially the reign of William II “The Good”. But the Sicilians never really got to rule themselves (some would say that even the unification of Italy only replaced one foreign dynasty with another), and there can be no argument that the cultural synthesis achieved under the Normans all those centuries ago is something to be proud of.