Welcome to the fourth instalment in this series, in which we look at Santa Maria Maggiore, one of Rome’s most famous churches, and two smaller but very interesting ones nearby – Santa Pudenziana and Santa Prassede.

My interest in this subject is historical and secular rather than religious, but it is not possible to discuss European history in the first millennium without reference to the evolution and controversies of Christian doctrine. I try my best to consider these issues objectively, but hope not to offend the devout.

Santa Maria Maggiore

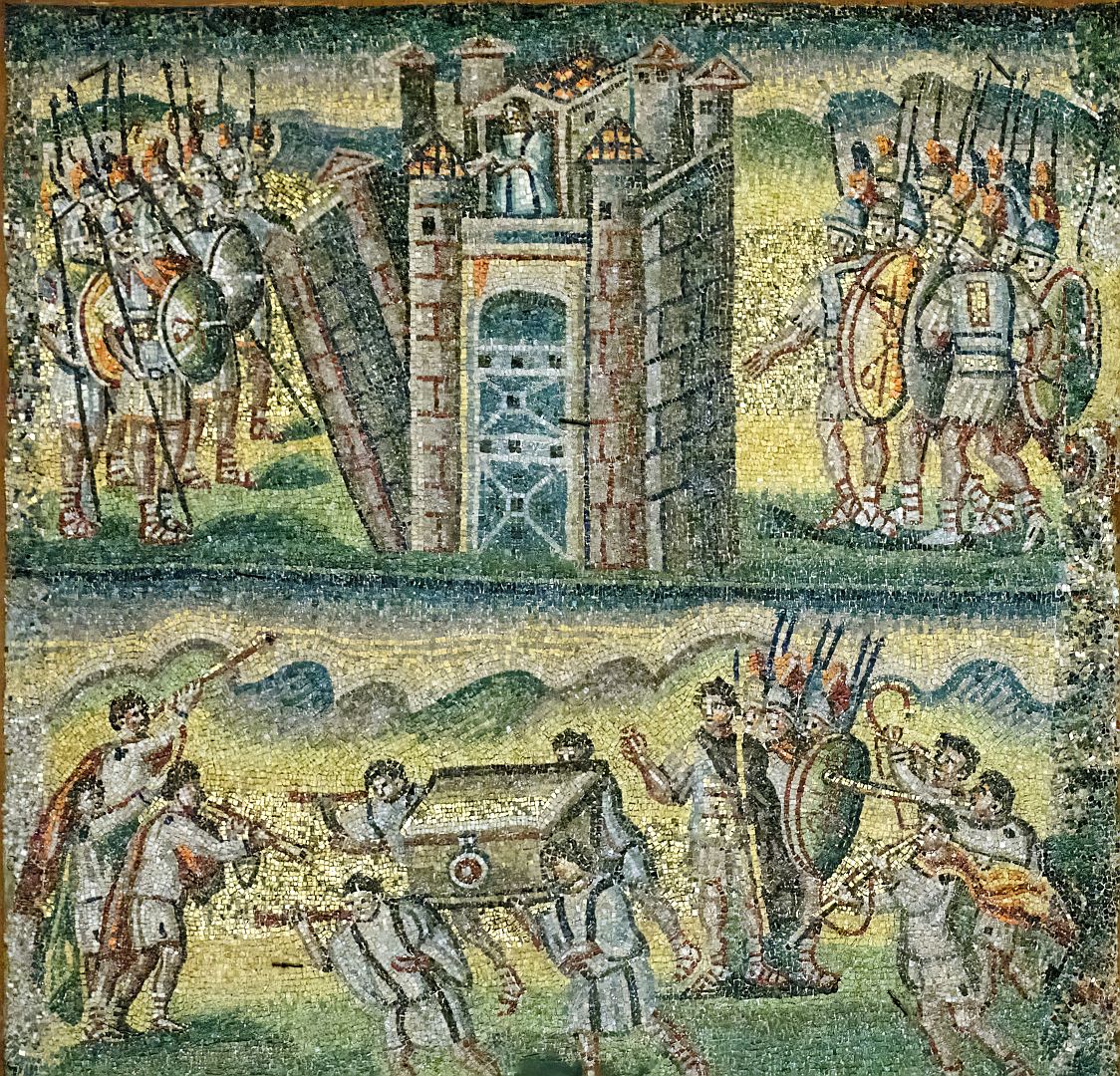

On a spur of Rome’s Esquiline Hill, not far from the Termini railway station, is the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore – Saint Mary the Great. These days the word “basilica” means a church that has been granted special privileges by the Pope, but in ancient Rome a basilica was just a large public building, built to a standard pattern on a rectangular plan, with a large central hall and side aisles divided from the central area by rows of columns. Santa Maria Maggiore is a basilica in both senses.

One interesting point about the special status of Santa Maria Maggiore is that when you step into it you are no longer in Italy, in a jurisdictional sense. Under the terms of the Lateran Treaty of 1929, in which the Catholic Church finally recognised the existence of the Italian state, the basilicas of Santa Maria Maggiore and St John Lateran remained little exclaves of Vatican City, analogous to the way that diplomatic premises are granted special status under international conventions. But my purpose here is to talk about the most ancient aspects of the building.

As is often the case, the exact origins of the building are a bit obscure, but it seems to have been built in the mid-400s on the site of another church which was about a century older. There is a legend about a miraculous summer fall of snow which indicated where the church should be built, but versions vary as to whether that refers to the older or the newer church.

What is known is that the central structure of the present church is that of the 5th-Century building. The church has been repaired, modified and extended several times over the centuries, with the most dramatic change being the addition of the huge baroque façade in the 1740s. That, added to the late medieval campanile and the domes, has the result that on first sight it really does not look very ancient at all.

But you have to look a bit closer. Unlike many of the terribly destructive modernisations of the 16th and 17th Centuries, this 18th-Century one left the 12th-Century mosaics on the original façade intact. So while that’s not paleochristian but medieval, it’s a good start.

Before we examine the insides, let us consider the fact that the church was dedicated to the Virgin Mary. This doesn’t sound particularly unusual to us now, but in the mid-400s, it was. Why is that? The answer begins with the fact that the Council of Ephesus had just concluded.

Some of the – for me anyway – more tiresome aspects of the history of the early Christian era are the endless controversies over Christology – the nature of Christ. Was he human, or divine? Or did he have both human and divine agency? If so, was his divine agency separate from that of God’s? How could his human agency not have been tainted by original sin? And so on, and on, and on, literally for centuries. Attempts to resolve these questions by reasoning led to all sorts of abstruse doctrines with no explicit basis in scripture, including the Trinity, the immaculate conception of Mary and more, all of which just spawned additional disagreements. Well-meaning emperors, popes and patriarchs tried – when they were not active disputants themselves – to resolve the issues by convening councils, but those councils usually ended up with enraged clerics hurling anathemas at each other, and sometimes furniture.

One such council, and an important one, was the Council of Ephesus in 431 which was called by the Emperor Theodosius II. I’ll spare you the details of all the issues in dispute (although if you are interested there is a fairly comprehensive summary on Wikipedia) but one of the outcomes was that Mary was now officially designated Theotokos, or “Mother of God” and that led rapidly to her promotion to the important position she has since occupied in both the Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. The Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, one of the first to be dedicated to the Virgin, was erected to commemorate this decision, which you will agree was a momentous one given the focus of intense veneration which she quickly became.

Now let us step inside. The first impression is of yet another large baroque church. There is an immense 16th-Century gilded ceiling which is “over the top” figuratively as well as literally. There is a huge baldacchino (canopy) over the altar, and at the rear of the nave over the door is a mock Roman temple façade with columns and tympanum, papal crest and a couple of angels. Above the altar is a dome and arches with every available surface covered with baroque wedding-cake style decoration.

But look at the columns that line the nave – although the capitals are more recent, they are real ancient Roman columns, recycled either from the church that stood on the site before this one, or from an earlier pagan temple (maybe both).

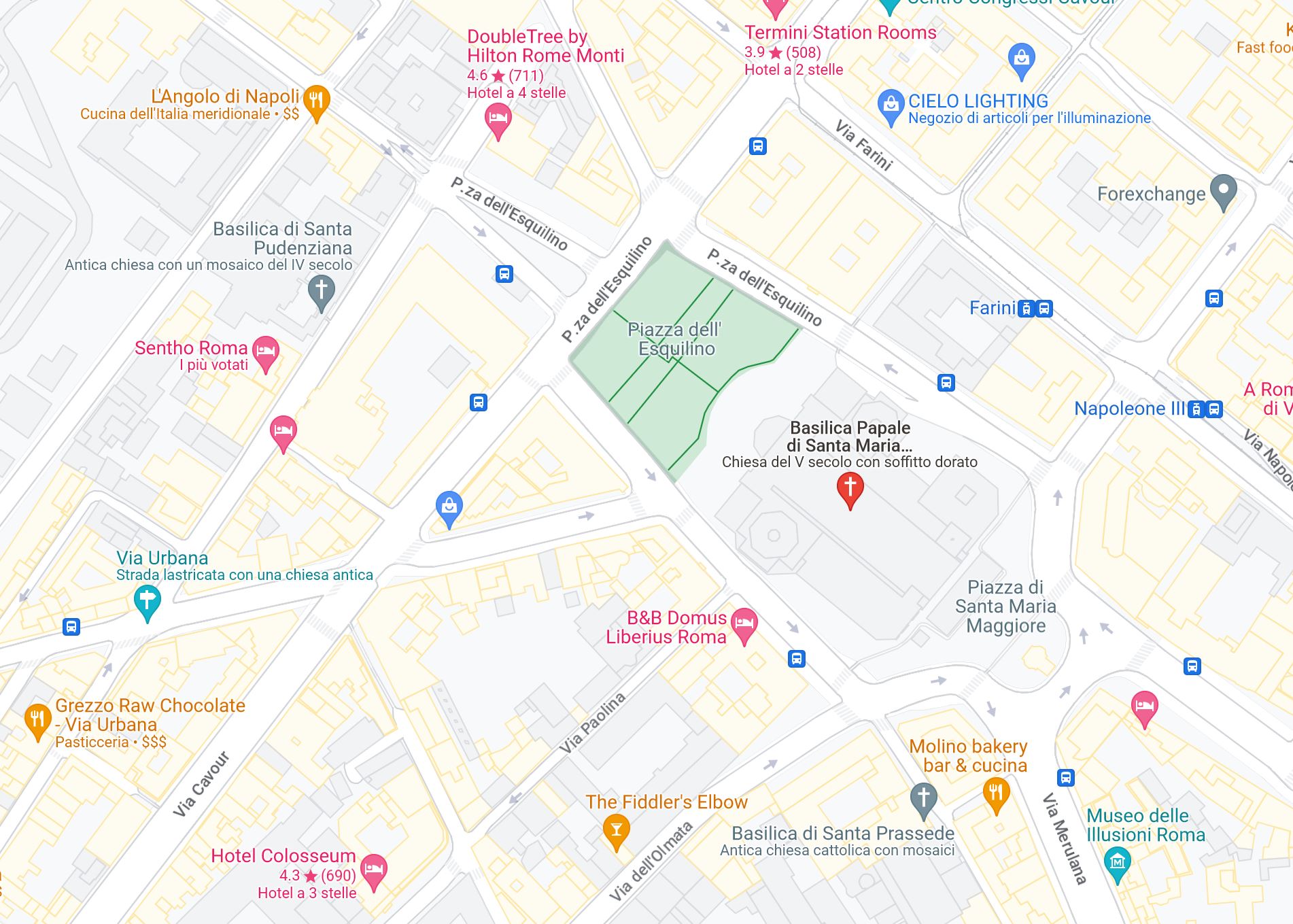

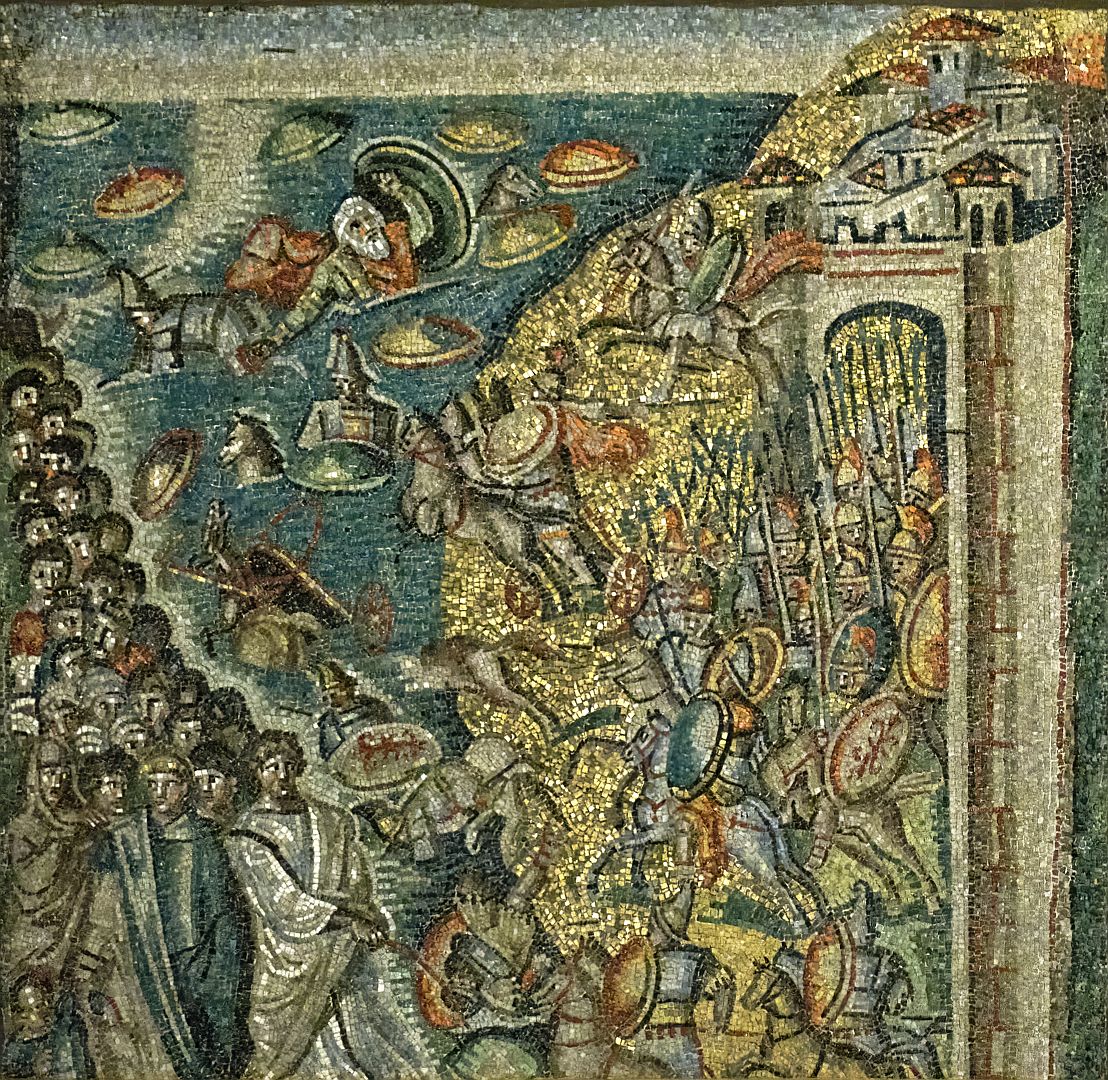

Above the frieze is a series of 5th-Century mosaic panels telling the story of Moses on the eastern side, and various other Old Testament stories on the western.

But the real glories of Santa Maria Maggiore are the 5th-Century mosaics on the arch separating the nave from the apse, and the 13th-Century mosaics in the apse itself. And they make a real contrast in Marian iconography.

Let’s do this backwards in time and look at the apse first. It is a magnificent example of a very conventional medieval image – Christ crowning His mother as Queen of Heaven. Christ has long dark hair and a beard. Mary wears her conventional shawl and outer blue cloak. Angels, saints, popes and cardinals are in attendance.

Now let us go back eight hundred years before that and look at what may be the earliest-surviving representations of Mary in western religious art, on the so-called triumphal arch. Remember, this was just after she had been proclaimed Mother of God by the Council of Ephesus. Here is a series of illustrations from the life of the Virgin – the annunciation, the nativity, and so on. But where is Mary? You would be forgiven for not noticing her at first – she’s not dressed in her normal blue cloak, but is the one dressed as an aristocratic lady from the late Roman period – complete with silk dress, necklace and tiara. Nor does she seem to have a halo (although, weirdly, Herod does). Nothing like the later representations of her.

And look for the three kings who appear in the adoration of the magi on the left side of the arch, and before Herod on the right. With their brightly-coloured tights and their Phrygian caps, we’ve seen those guys before, in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, built about fifty years after Santa Maria Maggiore. I had thought that version of them was unique to Ravenna, but clearly it was a conventional representation at the time. This stuff is really fascinating to late-Roman history nerds like me. (Note: I’ve since discovered a third version of them, on the ancient cypress-wood doors of Santa Sabina).

When we visited the church I was very pleased to see, as is often the case with the grand Roman basilicas, that the nave was empty of pews or chairs. This gives a sense of space and a much better idea of how the original must have felt (churches did not have seating until the late Middle Ages; before that you stayed standing or knelt on the floor).

Note: The original version of this article featured photographs of the arch mosaics taken with a high ISO and a short zoom lens and heavily cropped. The results were unsatisfactory and in October 2023 when I was next in Rome I took new ones with a longer lens with image stabilisation, which have replaced the earlier ones. It was still quite a challenge to process them.

Santa Pudenziana

The next church on our little itinerary is that of Santa Pudenziana, quite close by (see the map above). It is a very different sort of experience to Santa Maria Maggiore. The church is in a location described as the oldest place of Christian worship in Rome (although it is not the oldest surviving church building) and there seem to be reasonable grounds for making the claim. However the fabric of the building itself dates from the mid-4th Century which still makes it very old indeed.

Pudenziana (Latin Pudentiana) and her sister Prassede (Latin Praxedis or Praxedes) are supposed to have been the daughters of an early Christian convert in Rome called Pudens. Pudens probably existed – St Paul sends a cheerio on his behalf in 2 Timothy 4:21. There is a suggestion from linguistic evidence that Pudentiana might not have been a real person, and that her existence has been wrongly inferred from the phrase domus Pudentiana, which could have meant the “house (or family) of Pudens”. Whether she was real or not, a tradition sprang up that Pudentiana and Praxedis went around collecting the blood of martyrs before being martyred themselves in due course.

The church is on the site of a 1st-Century Roman house, so it is by no means implausible that the house was the home of a convert to Christianity (whom we may as well call Pudens) which in due course became an unofficial, then an official, place of worship.

It is hard to get a good sense of the building as you approach it – it is surrounded by other buildings including hotels and apartment blocks, and sits some way below the current street level, showing how much higher the ground level is in Rome these days (you can see a video explaining this phenomenon here). When you do get to it you see an architectural mish-mash which visually owes more to medieval and 19th Century renovations than to anything from the 4th Century.

Inside it is initially a bit disappointing as well – plaster-covered arches and a baroque altarpiece do not convey any sense of antiquity.

There is a notionally 4th-Century mosaic in the apse, showing Christ and the apostles and once described as the most beautiful in Rome, but it was heavily restored in the 16th Century, losing much in the process. The background, featuring an idealised Jerusalem and, in the sky the symbols of the four evangelists, looks original, and some of the faces of the figures on the left may be.

The rest of the decoration in the church is mediocre stuff from the 16th Century and later. I have to admit that the first time I visited here a few years ago I took a quick look around, sniffed disapprovingly at the redecorations, and quickly left.

But the evidence of the building’s antiquity is there in front of you – not in the decorations, but between them. Stuck unobtrusively between the plaster arches are the original Roman columns that support the nave, and – unusually for a redecorated church – the walls of the nave are the original unrendered Roman brickwork. At the top of the picture below you can see the herringbone pattern that is very characteristic of the era.

So, as it often turns out, it is worth pausing, looking carefully and thinking about what you see. You may then also reflect that during the weekly Sunday services (the church has been adopted by Rome’s Filipino community), the walls that look down on the congregation are the same ones that looked down on congregations over 1600 years ago.

Santa Prassede

The final church we are visiting today is on the other side of Santa Maria Maggiore and is dedicated to Pudenziana’s sister Praxedis/Prassede. I have not come across any explicit doubts about whether Prassede existed, as there are in her sister’s case, but by the same token I have not read of any evidence for her existence, other than tradition,

From the street, Santa Prassede is a bit unprepossessing. The first time we visited was an “are you sure this is the right place?” moment – but go inside, because you will be rewarded.

The church is later than the other two in this article, dating from the 700s, although there was a church on the same spot a couple of centuries earlier, and legend has it that the land was originally owned by the family of Pudens. It was commissioned by Pope Hadrian I to house the supposed bones of Prassede and Pudenziana. Shortly after it was built, around 820, the church was enlarged and redecorated on the instructions of Pope Paschal I, and it is these decorations on the arch and apse that – if you look past the inevitable baroque stuff lower down – make an overwhelming first impression.

Old Paschal wanted to make sure that he got the credit for this – under the both the triumphal arch and the apsidal arch you will see his monogram. And in the apse itself you will see him on the left of the group of figures surrounding Christ, holding a model of the church – since he was alive at the time of the depiction, by convention he is given a square halo. Either side of Christ, two female martyrs, presumably Prassede and Pudenziana, are being presented by Saints Peter and Paul. I don’t know who the saint on the far right is.

It’s a bit difficult to get a decent photograph of the apse mosaic from floor level, thanks to the ornate baroque baldacchino over the altar, so I had to take it in sections.

The church and its decorations are very impressive by 21st-Century standards, but must have been breathtaking indeed in the 800s. Shortly after it was built it was visited by a couple of pilgrims from a distant northern land – King Æthelwulf of England and his young son, the future Alfred the Great. At a time when most buildings in England would have been made of timber, you can imagine the effect this must have had.

For me one of the highlights of the church is the little chapel of San Zeno, built by Paschal to contain the tomb of his mother Theodora. Inside it is covered in mosaics – not to the same standard as in the main church, but they are charming and intimate. A lady labelled as Theodora is presumably Paschal’s mother, and since she too has a square halo she must still have been alive at the time.

In the photographs above the lady on the left is Theodora, Paschal’s mother, followed by probably Santa Prassede. Then comes the Virgin Mary, by now (400 years after Santa Maria Maggiore) conventionally dressed in a blue cloak with her head covered. I don’t know who the saint on the right is – it could be Santa Pudenziana, but if it were one would expect her to be wearing a martyr’s crown like her sister.

Also in the church is part of an antique pillar of polished stone – said to be that to which Jesus was tied when scourged in front of Pilate. This was identified in situ by Saint Helena, the mother of the emperor Constantine. Helena made a trip to the Holy Land during which, in addition to the pillar, she also managed to identify pieces of wood from the True Cross, parts of Jesus’s crib and various other relics which sparked a lucrative trade in such things for the next millennium or so. She also confidently indicated various sites mentioned in scripture such as Golgotha, the location of the Last Supper, and so on.

Note, April 2025: Santa Maria Maggiore has received a good deal of publicity recently after the burial there of the late Pope Francis. Expect it to be very busy for a while.