The Ducal Palace in Urbino was the home of one of the most famous and cultivated courts of the Renaissance. I have previously posted on Urbino – that article was really about the taking of a single large-format photograph, but also gave a quick history of the city, and how its court, under the warrior-humanist Duke Federico da Montefeltro, came to be considered the archetypal Renaissance court under the archetypal Renaissance ruler.

There is something almost theme-park-like about Urbino; the Duke clearly wanted it to be as beautiful as the architects of the day could make it, and so you drive a long way into a comparatively remote part of the country, and then you round a bend and there is a jewel of a small city. Here again is the photograph I took in 2008.

We recently revisited Urbino, which gave me the opportunity to take sufficient photographs to illustrate an article on the Palazzo Ducale (Ducal Palace), in which I can reflect a bit more on the Federico phenomenon. Here is a portrait of him as the donor of a religious work by Piero della Francesca, which I photographed in the Brera museum in Milan.

This painting was among the many works plundered from Central Italy by Napoleon, but rather than it ending up in the Louvre, Napoleon placed it in the Brera.

Federico famously preferred only to be painted in profile from the left, after losing his right eye to a jousting injury. And in order that this should not prevent him from seeing to his right on the battlefield, he had surgeons remove the bridge of his nose, giving that profile even more individuality. The bas-relief below shows this clearly. The other man is his (probable) brother Ottaviano Ubaldini della Carda, not the half-brother Oddantonio whom Federico succeeded, but a scholar and humanist who established Federico’s famous library for him.

Federico’s reputation is in a sense the result of a collaboration across the centuries. He himself was, it must be said, a careful curator of his own reputation, and then in the 19th Century his opinion of himself was enthusiastically confirmed by the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, who more or less defined the idea of the Renaissance as we think of it today, and who was looking for exemplars to support his argument. Later on Kenneth Clark picked up the theme in his seminal 1966 television series Civilisation.

That is not to say that Burckhardt and Clark fell for a cynical exercise in 15th-Century spin-doctoring. Federico really did receive a humanist education, he really did attract intellectuals to his court, and he really did try to be a philosopher-prince. Burckhardt’s story may be a bit of an oversimplification, but being only mostly right isn’t the same as being wrong.

A visit to the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino will quickly illustrate various aspects of this – starting with the FE DUX (Duke Federico) you see everywhere; he didn’t want you to be in any doubt as to whose place this was.

And the palace is the focus of the townscape without crudely dominating it; it is adapted to the contours of the hill and like Pope Pius’s recreation of the town of Pienza, this was about achieving beauty and proportion at scale as well as in miniature.

Inside there is a large arcaded courtyard with more inscriptions in honour of Federico. After buying our tickets we were ushered into an exhibition of works by a 16th-Century (ie, after Duke Federico) Urbino painter called Federico Barocci who is considered important and influential but who I must say seems a bit third-rate to me. His saints all have pretty faces and rosy cheeks as in the cheaper sort of devotional greeting cards. I guess it says something that Napoleon did not consider his works worth stealing. We did not stay long, and were soon heading upstairs into the Palace, which houses the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche.

A couple of wings were closed for renovation, alas, which meant that we could not access the balconies on the front of the building, but they had moved the important works from those wings so they could still be seen, and we were able to go up one of the towers.

There are many large halls, equipped with huge fireplaces to blunt the chill of the Urbino winters (a bit hard to imagine when we visited in a very hot July). One of the largest rooms is hung with expensive Flemish tapestries.

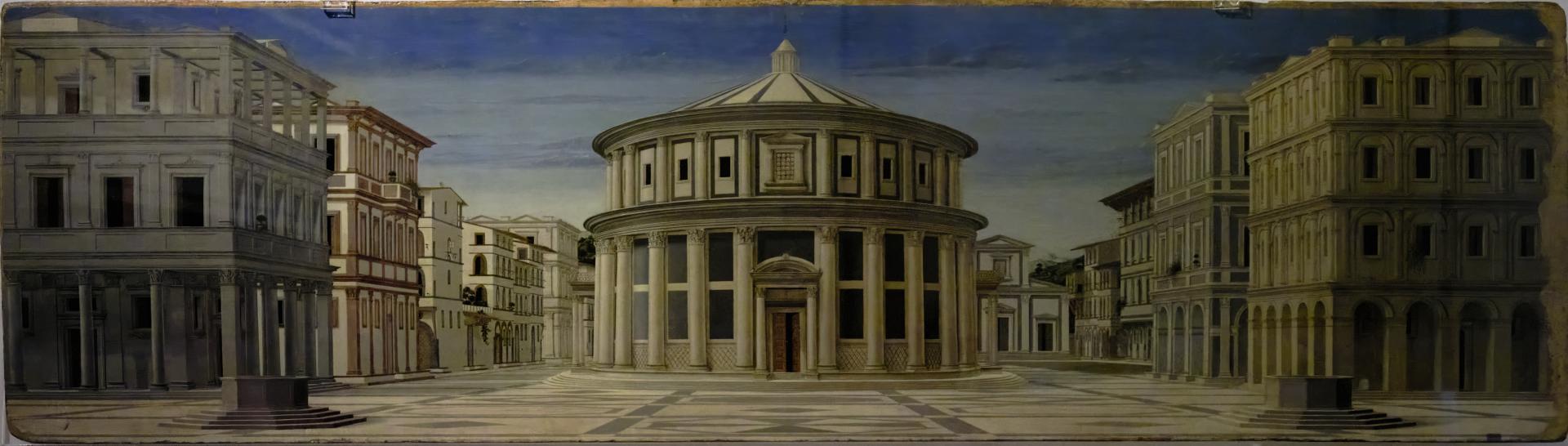

The “Ideal City”

There are two emblematic works associated with Urbino that are still kept in the palace. The first, a painting of an “Ideal City” was long attributed to Piero della Francesca, then to several others in turn. Now its creator is more cautiously described as “unknown artist”.

There is another “Ideal City” painting from Urbino whose attribution to della Francesca is accepted; that one is now in the United States.

The depiction of ideal cities was very much a Renaissance thing and it is quite in character for Federico to have commissioned one or more. Renaissance artists were often architects as well, meaning that they had to have a good grasp of applied mathematics. One way to acquire this – and of course to demonstrate it – was to practice the art of perspective. Moreover when you had big aspirations to redesign a whole town, as Federico clearly did, then imaginary cityscapes, especially those that embodied “classical” Roman aesthetic values, would have had obvious attractions.

The Flagellation of Christ

The second emblematic work, The Flagellation of Christ from 1468 or 1470, is unambiguously attributed to Piero della Francesca (because he signed it). It is a mysterious piece the meaning of which continues to elude art historians, although that has not prevented them coming up with many ingenious theories. One popular suggestion is that it is a coded reference to the death, in suspicious circumstances, of Federico’s predecessor and half-brother Oddantonio, who according to that tradition is the blond barefoot figure in the centre of the group on the right. Oddantonio’s government had not been popular in Urbino and when Federico succeeded him he had promised not to investigate his death or hold anyone to account – this is argued to be the reason why this commemoration had to be so cryptic. Just to add spice, there are also theories that Federico himself was in some way complicit in Oddantonio’s death.

Other interpretations centre around the intriguing figure of Bessarion, a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher and notable scholar who nonetheless became a cardinal in the Catholic Church and, in a vain attempt to avoid the fall of Constantinople to the Turks, worked unsuccessfully for a reunification of the eastern and western churches. By that reading the picture could be a lament on the destruction of Eastern Christendom. There is certainly a good argument that the Herod figure is meant to be John VIII Palaiologos, the penultimate Byzantine Emperor – he is wearing the red slippers that only emperors could wear, and the same funny hat that he is shown wearing in other likenesses. So I think that the answer to the riddle has to be found in that direction. But no doubt new interpretations of this enigmatic painting will continue to appear: I don’t think anyone has managed to work in the Knights Templar yet, so there’s an opportunity.

Kenneth Clark was particularly enthusiastic about it, calling it the “best small painting in the world”. One additional mystery is how it survived at all. It was apparently discovered folded in half (or cut in half, according to the panel next to it in the palace) which explains the damage to the face of the Christ figure.

The Studiolo

One of the famous rooms in the palace is the so-called “studiolo”, or little study. It is a tiny room, with a chapel attached, decorated with some of the finest examples of trompe-l’oeil intarsio, or wood inlay, to be found in Italy. It is easy to imagine Federico in here, reading dispatches from his commanders, or letters from other rulers, or perhaps studying a copy of some ancient text that he had acquired for his library.

The Art of War

As I explained in the earlier article, as a second son, (originally illegitimate, but legitimised by the Pope) Federico’s intended career was as a condottiere or mercenary captain. When he succeeded to the Dukedom he found that the duchy’s finances were in a very poor state, so he kept going in that line of work to bring in an income, with the additional benefit to prospective employers that he was not just supplying an army, but an alliance. He was very successful in the profession of arms, so when he was celebrating his achievements, his military prowess tended to be prominent.

In most pictures of Federico, such as the one from the Brera shown above, he is either wearing his armour, or he has it beside him. And the surgery on his nose would always be a reminder that he had been a soldier before he was anything else.

It turns out that Federico commissioned a celebration of his martial profession as part of the external decoration of the palace. If you look at the picture below, there is space for a frieze (now just a blank strip) along the bottom of the wall around the square, above the bench where people are sitting.

Federico was apparently a keen student of the works of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, especially his book on military machines, and so the frieze he ordered was to feature diagrams of those as well. According to Vasari they were originally coloured.

After a couple of hundred years of being out in the weather (and perhaps of the citizens of Urbino leaning against them) the images had become badly deteriorated, and 1756 the Papal governor ordered that they be removed and brought indoors, where they stayed until the 1940s. They weren’t visible when we were last here in 2008, but they have been brought out again and put on display. Some of them are indeed so badly deteriorated that it would be impossible to make out their subject were it not for helpful illustrations alongside, but here are a few of the better ones.

The End of the Story

As I said in my earlier article, the flame of Urbino burned brightly, but not for long. The duchy passed into the hands of staunch Papal allies, the della Rovere family, who put another floor on the palace and furnished it to their own tastes.

But the party was already over, and in due course the title was extinguished and the duchy was formally absorbed into the Papal States. From a humanistic intellectual lighthouse to a provincial backwater, Urbino’s fall was far indeed. There is of course one benefit from that long period of decline, which is that architecturally the city remained frozen in time at the period of its greatness. It is now a university town and there is a bit of energy about the place once again. So nowadays you can visit this improbably beautiful city and imagine what it must have been like when it and its ruler were “The Light of Italy”.