The Etruscans were pervasive in Central Italy, but their legacy was largely overwritten by the Romans. Three years ago we visited a recently discovered Etruscan tomb in Sarteano, and then went on the trail of Lars Porsena of Clusium.

Who were the Etruscans?

If you had asked me a couple of decades ago what I knew of the Etruscans, my answer like Gaul would have been divided into three parts. First, they lived in the area now known as Tuscany, which derives its name from them. Second, they spoke an unknown language unrelated to Latin. Third, Rome had been ruled by Tuscan kings until they heroically overthrew the last one, Tarquinius Superbus, ushering in the Republican Period. I then might have quoted a couple of half-remembered lines from Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome, the part about Horatius defending the bridge that begins:

Lars Porsena of Clusium, by the nine gods he swore

That (something something something) should suffer wrong no more.

Not surprisingly, it turns out that things are bit more complicated than that.

Firstly, it is true that they started out in what is more or less modern Tuscany, although their original homeland extended eastwards into what is now Umbria, to the Tiber River and Perugia. At its widest extent their civilisation extended north into the Po Valley as far as Mantua, and to the south it reached down to Campania and Naples, so it well and truly included Rome. On that southern border they came into contact with the Greek colonies in Italy, absorbing many cultural influences.

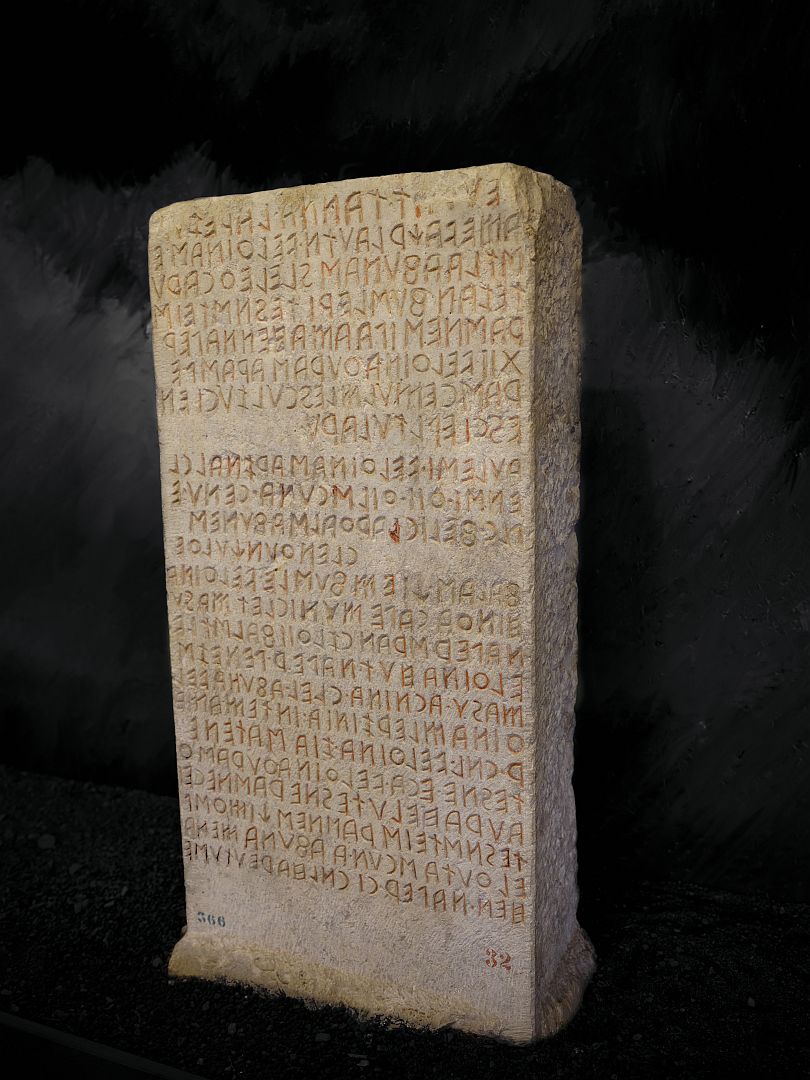

As for the language, it is tantalising how little we know of the Etruscans’ culture, given how much we know about where they were, when they were, and what other cultures they interacted with, several of which were literate. We know that their language was indeed not Indo-European, and that it (and they) therefore probably pre-dated the migration of Aryan peoples into Europe. We also know more or less how it sounded because when the Etruscans became literate they adopted a version of the Greek alphabet, albeit written from right to left. In fact, in most of the museum exhibits I have seen, they even flipped the Greek characters into true mirror-writing, which makes it look odd indeed until you work out what is going on (note 1).

But they left nothing but funerary inscriptions, and a tiny number of other documents recording religious rituals or commercial contracts, a couple of which are actually in parallel Etruscan and Latin language versions.

Finally, they left no descriptions of themselves, and the only descriptions we have are from early Greek writers, or Roman historians writing many generations later, which included the bits about the Etruscan kings of Rome. Given that Rome defined much of its early history by stories of wars in which the Etruscans were the bad guys, the traditions on which those historians – mainly Livy – were relying were probably not entirely objective. And like all such societies in that era, the great battles and glorious victories they celebrated were probably not much more than cattle raids. Finally, the Etruscan civilisation didn’t fall as such. Instead it was gradually romanised until it became indistinguishable from that of Rome, and faded away.

But it isn’t just that Etruria became Roman; some aspects of what we think of as Roman culture have Etruscan origins. It turns out that certain words which modern European languages inherited from Latin, including the English person and military, are thought to be derived in turn from Etruscan originals, so there are some distant modern echoes of that otherwise vanished language.

Chianciano and Sarteano

In June 2018 we were staying in the southern Tuscan town of Chianciano while waiting to hear whether our offer on an apartment in Umbria had been accepted. Chianciano is divided into a charming little medieval hill town and a newer town (Chianciano Terme) on the eastern slope of the range of hills that divides the Valdichiana from the Val d’Orcia. Chianciano Terme, as the name implies, is a spa town. It is mostly composed of mid-20th Century hotels catering for elderly patients who came there to take the waters for their livers. It’s a nice place and in particular the old town has some lovely views eastwards across the Valdichiana to the Umbrian hills. A particularly good place to look at the view was from the balcony of the Bar Pasticceria Centro Storico (below).

When the new town was being built they uncovered quite a few Etruscan tombs, and Chianciano now has a decent little museum in which to display the contents.

We have to admit though that a better Etruscan museum is in a town called Sarteano, about halfway between Chianciano and Monte Cetona, a few kilometres south.

As is almost always the case, the Etruscan remains around Sarteano are mostly tombs. When a few finds were turned up in the mid 19th Century, the aristocrat on whose land they were found financed some excavations which were scientific enough by the standards of the day, but proper archaeology as we understand the term had to wait until after the Second World War.

And the finds are still happening. One of the most spectacular occurred in 2003, and Lou had established that by paying a bit more on top of the price of the museum ticket, you could actually make a visit to that site on Saturday mornings. So we duly paid, and the following Saturday morning we made our way to the site following the directions given by the museum attendant (head out of town until you see a bunch of car dealers, then turn left just after the Rover sign). The road became a dirt track, then we eventually bumped to a halt in a field and got out to investigate.

The first thing to say is that it is in an absolutely splendid location, augmented in this case by the fact that it was a flawless summer’s morning, with all sorts of flowers growing around, the air heavy with their scent, and resonant with the sound of bees and birds. We were standing on the broad shoulder of a range of hills that runs north-south and which separates the Valdichiana from the Val d’Orcia. Behind us to the right was the tall conical peak of Monte Cetona. Ahead, to the east we looked down into the Valdichiana which is a patchwork of fields and vineyards thrown over low rolling hills. On one such hill in the middle distance to the left was the town of Chiusi (the ancient Clusium of “Lars Porsena of Clusium“), in the distance was Lake Trasimeno, and on the distant skyline were the Apennines.

The area appears to have been a necropolis, or burial area, and it seems to have been used for a period of several hundred years, stretching into the 1st Century AD. At one end of the excavated area is an oval structure of travertine stone which looks like a stage, which the archaeologists, plausibly enough, have decided was a stage, presumably used for pre-interment ceremonies. The entrances to the tombs are long passages cut into the hillside and lined with travertine; as the whole area is on a slope the passages can cut into the earth while being mostly horizontal themselves.

Over the next quarter of an hour a dozen or so more visitors arrived, then there was a hallooing from a bit further down the hill which turned out to be coming from our guide. She was an archaeologist who had taken part in the 2003 excavations herself and been present at the discovery of the tomb we were about to see.

The tomb we had come to see is called the Tomba della Quadriga Infernale (Tomb of the Infernal Chariot) because of the frescoes. That they have survived at all is quite lucky. Some finds inside date from the early Middle Ages and suggest that it was actually used as a dwelling in that period. Or perhaps a refuge in times of war, as even by the standards of the time it can hardly have been a salubrious place to live. Then – in the 1940s, they think – grave robbers broke in and did some frightful damage to one of the frescoes. Fortunately much of the entry passage was buried by then, and the earth protected the other paintings.

We split into two groups to go in; Lou and I were in the first group. All the other people in our group were Italians, so our guide spoke in Italian, but very clearly and not too fast so we were able to follow most of what she said. Of course, we had visited the museum a couple of days earlier, so the vocabulary was familiar. You were allowed to take photos without flash, so I did, but just on my phone.

All the surviving paintings are on the left side as you go in. If there were any on the right, they might have been destroyed when the tomb was used as a dwelling in the Middle Ages. The first is what gives the tomb its name – it is a demon driving a chariot, drawn by a team of lions and griffins.

He is heading towards the entrance of the tomb, which leads scholars to conclude that the charioteer is heading back to the world of the living after having carried a dead soul down to the underworld, in order to pick up the next passenger. This in turn leads those scholars to identify the demon with Charon, although we are more familiar with him as a boatman ferrying souls across the Styx. You can tell he is a demon, apparently, because of his large lower canine tooth, his red hair and white face. They didn’t mention the rouged cheeks and lipstick.

Beyond the demon in the chariot is a picture of two men – one old and one young – embracing. The explanation back in the Sarteano museum had been that the younger one is the recently deceased, greeting his long-dead father in the underworld. The guide did at least acknowledge the other possibility that they were lovers – accepted enough in ancient Greece and therefore presumably possible in ancient Etruria.

Then at the back of the tomb there was a three-headed serpent and a hippocampus or sea-horse. There was a sarcophagus at the end of the tomb which had been smashed up by one of the later intruders, and later reassembled by the archaeologists. Some human remains had been found among the bits, which on analysis had been found to be those of a male in his sixties.

There were several extraordinary things about all this. One was that the paintings had survived at all after more than two thousand years. Another was that they had survived in such good condition. And another was that we could just wander in there and look at them – no hermetically sealed system, no sheets of perspex between us and the paintings, and no ultrasonic alarms to prevent you getting too close. Although given that one lady almost backed into the charioteer before being warned off by the guide, maybe that might have been a good idea.

It was also fascinating to think that when we were first in these parts at the end of the 1990s, the tomb had yet to be discovered. Afterwards Lou and I lingered up above in the sunshine, admiring the view which – minus the odd high-speed railway line – was pretty much as the Etruscans would have seen it, and pondered how much else might be beneath our feet.

Chiusi

Chianciano is quite close to the town of Chiusi, which as I said is the Clusium of the ancients. In the first twenty years or so of our visits to Italy, Chiusi to us was a motorway exit on the way north from Rome Airport to the Val d’Orcia in Tuscany, and a handy shopping centre and supermarket at a place called Querce al Pino, called – significantly – Centro Etrusco. If, instead of continuing towards Montepulciano you turn east towards Città della Pieve, you go through the modern town of Chiusi Scalo which is fringed by light industry and some now shabby-looking 1950s social housing.

Once we had worked out that there was more to Chiusi we paid a couple of visits to the old town, which has much to recommend it. It is pleasantly compact and neat, up on the hilltop where those Etruscans once decided to make a home. Being close to such tourist drawcards as Orvieto, Montepulciano and Pienza it has never really cracked the foreign tourist market, but in many ways this is no bad thing. One can only buy so many fridge magnets.

We have a definite tendency, when turning up in towns for the first time, to do so on unsuitable days. In this case we got a double because not only was it market day (where do they put markets? In the car parks) but also the annual feast day of St Mustiola, one of the patron saints of Chiusi. So the market had extended hours, and later when we tried to get into the duomo there was a mass going on. However we got lucky and found a parking spot and wandered around a bit.

We walked up to a little park which is on the site of the old acropolis and which is full of various bits of antique stonework turned up in the 18th and 19th centuries and too heavy, or not good enough, to sell to foreign collectors.

The Etruscan Museum is quite large, and worth a visit. Around the town, Etruscan and Roman remains are everywhere. Several buildings have obvious ancient stonework incorporated in their walls, and next to the duomo there is an Etrusco-Roman cistern of which the base is Etruscan and the upper part Roman. The whole thing has been converted into a bell tower for the duomo by the addition of some medieval brickwork on the top. You can climb it for excellent views of the town and the surrounding countryside.

Nearby there is the entrance to something called Il Labirinto di Porsenna of which we took a guided tour. The story of Lars Porsena’s tomb being hidden under Chiusi and protected by a labyrinth goes back a long way, being mentioned by the Roman historian Pliny the Elder. So when the “labyrinth” was rediscovered in the 1920s people were quick to make the association. The truth is a bit more prosaic: it is in fact a system of aqueducts and drains that made up the town water supply in antiquity. The townspeople put it to good use in the 1940s as air-raid shelters.

There are other signs of Etruscan influence. The main street is called Via Porsenna and I was hoping to find a “Lars Porsena Bar”, but we did not find one. We did at least eat at a little restaurant called “Osteria Etrusca” where one of the pizza toppings was called “Pizza Etrusca” and consisted of sausage and gorgonzola cheese. No doubt its authenticity is based on scholarly research, although the menu omitted any citations.

I have enough material to do a separate post on Chianciano one day. And we are not finished with the Etruscans either, because the following year we visited the town of Tarquinia in the northern part of Lazio, which has an extensive Etruscan necropolis.

note 1: In the excellent National Archaeological Museum of Umbria, in Perugia, I saw an inscription in the Umbrian language, which unlike Etruscan is Indo-European and in the same linguistic family as Latin. It used the Latin alphabet, but was written in mirror-writing like Etruscan.