In a pretty location in Umbria you may visit an artistic masterpiece of the Renaissance: Signorelli’s frescoes in the cathedral of Orvieto.

Orvieto is a town in western Umbria with a spectacular situation – the area abounds in outcrops of “tufa” – rock formed from volcanic ash, around which the softer rock has eroded away. This makes such sites good choices for defensibility, and it seems that there has been a settlement here from before Etruscan times. The name itself is said to derive from the Latin Urbs Vetus, meaning “the old city”.

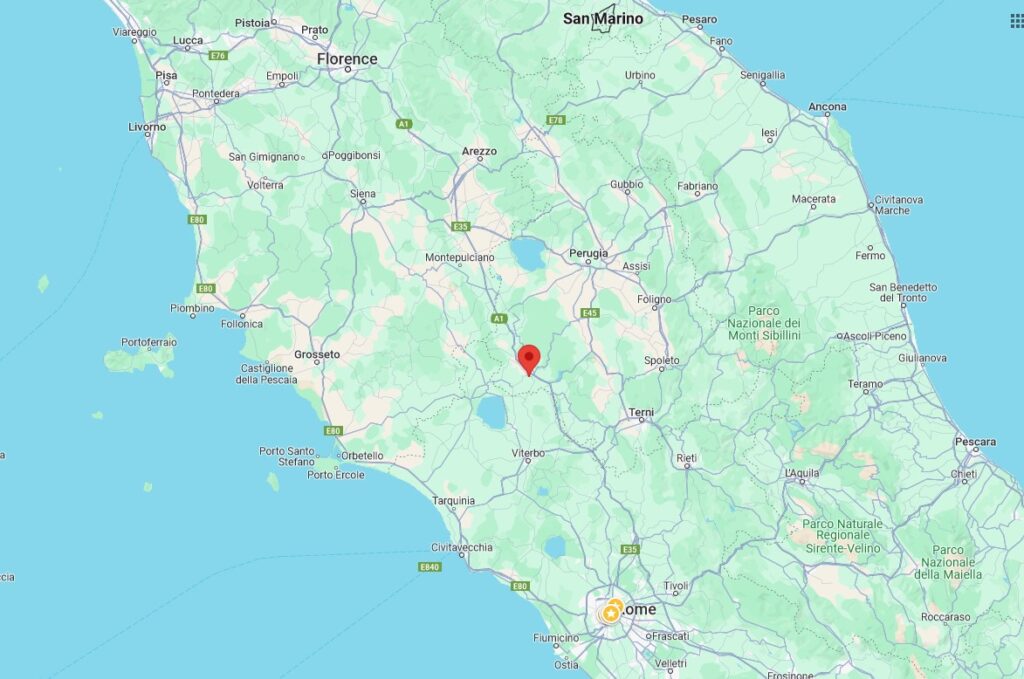

Although in the region of Umbria now, Orvieto is located west of the Tiber River and so it would not have been part of the ancient territory of the Umbri, nor, for the same reason, would it have been part of the ancient Roman province of Umbria. The modern region of Umbria, with several other regions, was created when the Papal territories were annexed by the Kingdom of Piedmont during the unification of Italy, and its modern area only approximates that of its ancient one. So Orvieto doesn’t feel particularly Umbrian – the landscape and architecture have more in common with northern Lazio towns like Montefiascone and Caprarola.

As the map shows, Orvieto is approximately halfway between Rome and Florence, and on both the main north-south motorway and the high-speed railway line. This means it is well-placed to receive a lot of tourists, which it does – but there has to be a reason for them to want to come. That reason is an artistic and architectural heritage that seems out of proportion to a place of such modest size. But some important things have happened here. Thomas Aquinas lectured at the university, and from the mid-1200s Orvieto was one of the cities to which Popes removed themselves when conflicts in Rome became too dangerous.

These days the attraction of Orvieto is largely based on the extraordinary duomo, or cathedral. While the duomo dominates the town when seen from a distance, you don’t actually see it as you walk along the narrow streets from the funicular which brings visitors up from the railway station and the car park. Then you suddenly turn a corner and there it is – and it is breathtaking.

Next to the duomo is an impressive medieval building – the Papal Palace, used as a residence when the Pope was in town. These days it houses the tourist office where you buy your ticket to visit the duomo.

The Duomo

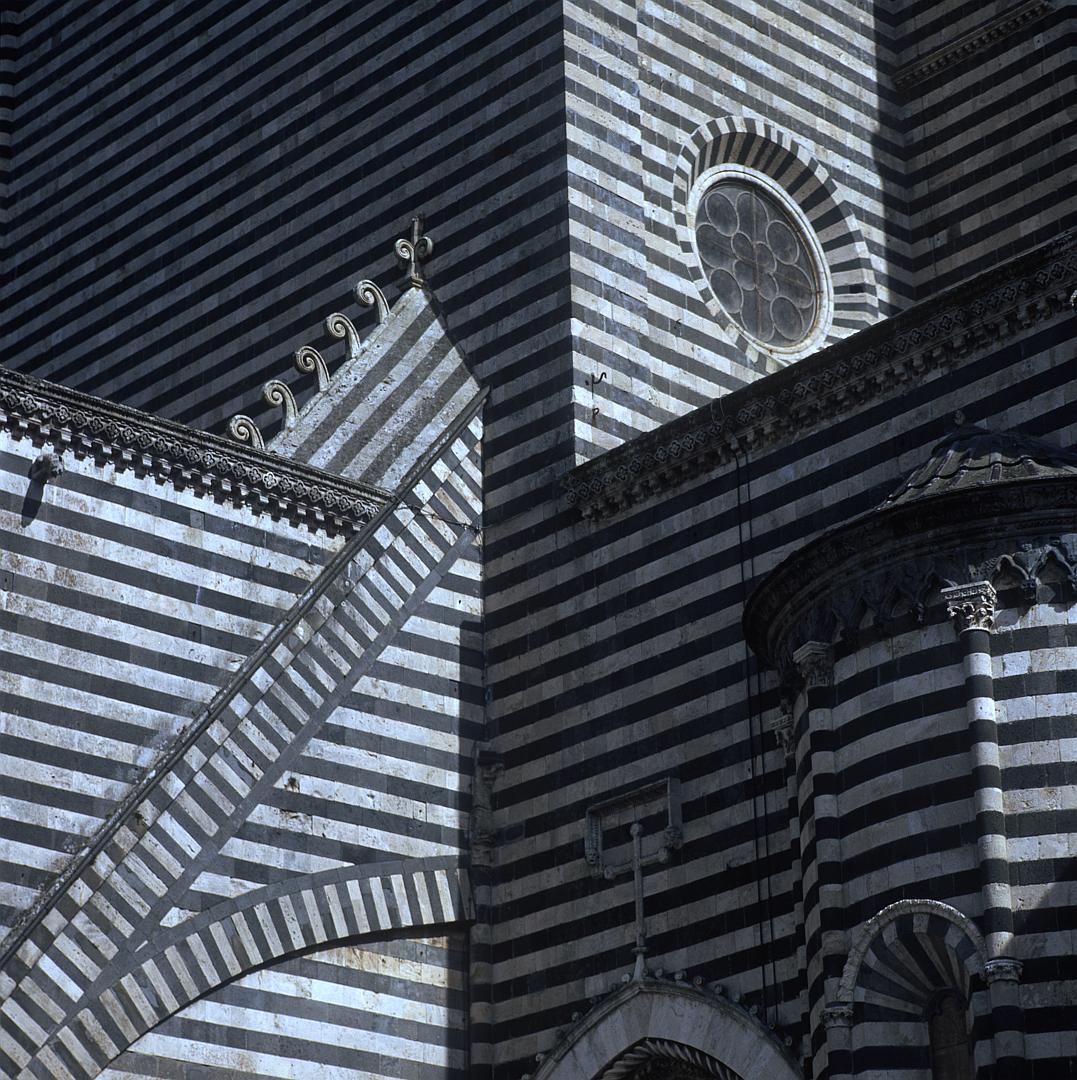

Towards the end of the 13th Century, the town authorities decided to build themselves a magnificent church, to be dedicated to Santa Maria Assunta, and built of alternating layers of white and black stone, like a giant liquorice allsort – a style common in Tuscan cities like Siena and Pistoia. Progress was a bit slow; the town kept running short of money, and every now and then plague and war interrupted things. In fact it took about three hundred years, so it started in the Romanesque style, most of it was Gothic, and there were some Renaissance bits towards the end.

Apparently one of the more serious problems first encountered was that the structure didn’t appear to be strong enough to carry its own weight – a Sienese architect was brought in who added buttresses and other features based on the duomo at Siena.

And it was that Sienese architect – a chap called Maitani – who designed the first of the cathedral’s masterpieces – the magnificent Gothic façade.

The façade is the most prominent architectural feature in Orvieto and it can be seen clearly in the distant view of the town in the first photograph above. Sometimes, when the setting sun hits its golden mosaics, it shines like a beacon far into the distance. The mosaics date from the late 14th Century, but most were replaced and redesigned in the 15th, 18th and 19th Centuries.

At the base of the four piers of the façade are a series of bas-reliefs depicting stories from the old testament, and a Last Judgement with gruesome-looking devils carrying away the souls of the damned. It is thought that some of the work was by Maitani himself, but that three or four other master sculptors must have worked on it. My favourite part of it is a “Jesse Tree” which was a favourite motif in Christian iconography, showing various ancestors of Christ, starting with Jesse, the father of King David, in the branches of a tree. This has been compared to a medieval manuscript illumination, but carved in marble – I would certainly agree with that description.

Around the door you will see some of the most extraordinarily delicate carving, of marble inlaid with beautiful mosaics. This sort of portal carving is very common in Gothic cathedrals, but seldom is it as elegant as this.

The Interior and the Cappella Nuova

Once inside the “liquorice allsort” one tends to be struck by the comparative simplicity. I like this, as it is probably close to the original impression one would have had in the Middle Ages. Some writers seem to find it too stark a contrast to the glories of the façade, and if you agree with them, then be patient, because the best is yet to come.

And the best – which is what you have come to see – is one of the most memorable works of the 15th-16th Centuries, which is saying something. On one side of the nave is a chapel referred to variously as the Chapel of the Madonna of San Brizio or simply the Cappella Nuova, or “New Chapel”. “New”, in this case means that it was commissioned in 1408, a bit over a hundred years after work on the cathedral commenced, but consideration about how to decorate it did not begin until the mid-1400s. Perhaps it was a question of money, because that certainly turned out to be a constraint in the decades to come.

In 1446 negotiations were started to secure the services of one of the most famous artists of the day, the Dominican monk born Guido di Pietro, later called Fra Giovanni da Fiesole, but known to anglophone art history as Fra Angelico (NB: not Frangelico – that is a hazelnut-flavoured liqueur). In Italy he is usually called Il Beato Angelico, the blessed Angelico. The title eventually became official in 1982 when Pope John Paul II formally beatified him. I have some photographs of his frescoes from the monastery of San Marco in Florence, which I will make the subject of another post one day. (edit: here is that post.)

In 1447 the cathedral authorities signed a contract with Fra Angelico, and he did spend one summer in Orvieto, preparing designs and executing a couple of ceiling panels – in which he was assisted by the young Benozzo Gozzoli. A combination of papal demands on Fra Angelico’s time and possibly the difficulty of finding the money to pay him meant that he did not return, although apparently Gozzoli stayed on and continued the work for a while.

Fra Angelico died in 1455, and for the rest of the 15th Century no real work was done on the chapel, although the scaffolding remained in place. Orvieto itself went through some hard times with a period of civil disorder caused by the usual conflicts between rival wealthy families, which cannot have helped with the civic revenues.

Every now and then as finances permitted, attempts were made to find a painter to carry on the work, including the great Perugino, who characteristically kept the Orvietans hanging for a decade or so before finally turning them down. At that point, the choice fell on Luca Signorelli.

Signorelli came from the town of Cortona on the border of Tuscany and Umbria. In 1499 he was around 50 years old and presumably at the height of his powers. He had contributed to the decoration of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, and also to the famous paintings in the monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore near Siena, but it was this work in Orvieto that established his reputation in art history. As part of the contract he undertook to complete those parts of the chapel for which Fra Angelico had left drawings, but these were only for the rest of the ceiling panels. Since Fra Angelico’s work featured a Christ in Judgement, Signorelli proposed to continue the theme of the Apocalypse and Last Judgement, in keeping with Fra Angelico’s intent, but also picking up the eschatological tone of the carvings on the cathedral façade.

I have seen a tourist website which states that the Orvieto Last Judgement is based on that of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. This is completely the wrong way round! Signorelli was first, and Michelangelo came after. Any similarities – which there are – are the result of Michelangelo drawing inspiration from Signorelli, and not vice versa.

The Frescoes

Let’s start with the ceiling, which is the only place you can see any work by Fra Angelico. These are the two panels featuring Christ in Judgement and The Prophets.

The rest is all by Signorelli. The upper walls contain several scenes, drawn from the biblical account of the apocalypse and medieval works. In (I think) chronological order, they are The Rule of the Antichrist, The Apocalypse, The Resurrection of the Flesh, The Damned in Hell and The Elect in Paradise. You may find them given slightly different names in different sources.

The Rule of the Antichrist

The central figure in this panel is the false Christ preaching. He is rather shockingly depicted as similar to the real one, but with the devil whispering in his ear. Our old friend the art historian Vasari claimed to have identified real people in the crowd around him, including the young Raphael as the well-dressed long-haired chap in red tights with his hands on his hips. However some modern sources cast doubt on this.

It had not occurred to me until I started writing this article, but this fresco was painted very shortly after the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola was convicted of heresy and executed in Florence. Savonarola preached a Taliban-like message of radical asceticism, and for a while was the effective ruler of Florence, declaring it to be the new Jerusalem and the world centre of Christianity. Savonarola was famous for his “bonfires of the vanities”, in which rich Florentines offered their treasures for destruction, and sure enough, on the ground in front of the Antichrist is a pile of such offerings. It seems very probable that people would have made the connection, and moreover that the church authorities would have wanted them to. Then I noticed that behind the Antichrist Signorelli has depicted a group of disputing clerics, prominent among whom are several in the black and white Dominican habit that Savonarola would have worn. I wonder if that was part of the message as well? Not that Savonarola had been the actual Antichrist, but that this sort of puritanism was dangerous heresy.

Elsewhere in the scene, bad stuff is happening all over the place. People are being persecuted and executed for not following the Antichrist. and in the central background the Antichrist is performing bogus miracles. At the top left is the end of this particular part of the story, where the Antichrist has dared to attempt to ascend into heaven, but is quickly dispatched by the Archangel Michael. A group of people below, presumably the Antichrist’s followers, are killed in the collateral damage.

At the lower left stand two men dressed in black, solemnly observing the scene. These are Signorelli himself and Fra Angelico. Signorelli cannot have met his predecessor, and I do not know on what the likeness was based, but it was a generous gesture on Signorelli’s part to include him.

In this as in the other main scenes, you will notice a clever artistic trick by Signorelli – at the bottom of each scene some of the characters look as if they are actually standing on ledges that are part of the structure of the cathedral. It is quite a skilful bit of false perspective, given that you are looking at it all from below. It is not the only part of the chapel where he plays these sorts of games.

The Apocalypse

This scene is painted over the archway that divides the chapel from the nave of the duomo. On the right, in the foreground the Old Testament King David and a Sibyl are predicting the end of the world. Behind them, someone is escaping from a collapsing building, and people are being led to execution. In the distance, a city is in ruins and ships are borne high on huge waves.

On the left, flying devils are laying waste to the earth with fiery breath, while people below flee in panic.

As elsewhere, the foremost figures – David and the Sybil on the right, the terrified refugees on the left, have been painted as if they have come out of the paintings and are standing on the actual architecture of the cathedral.

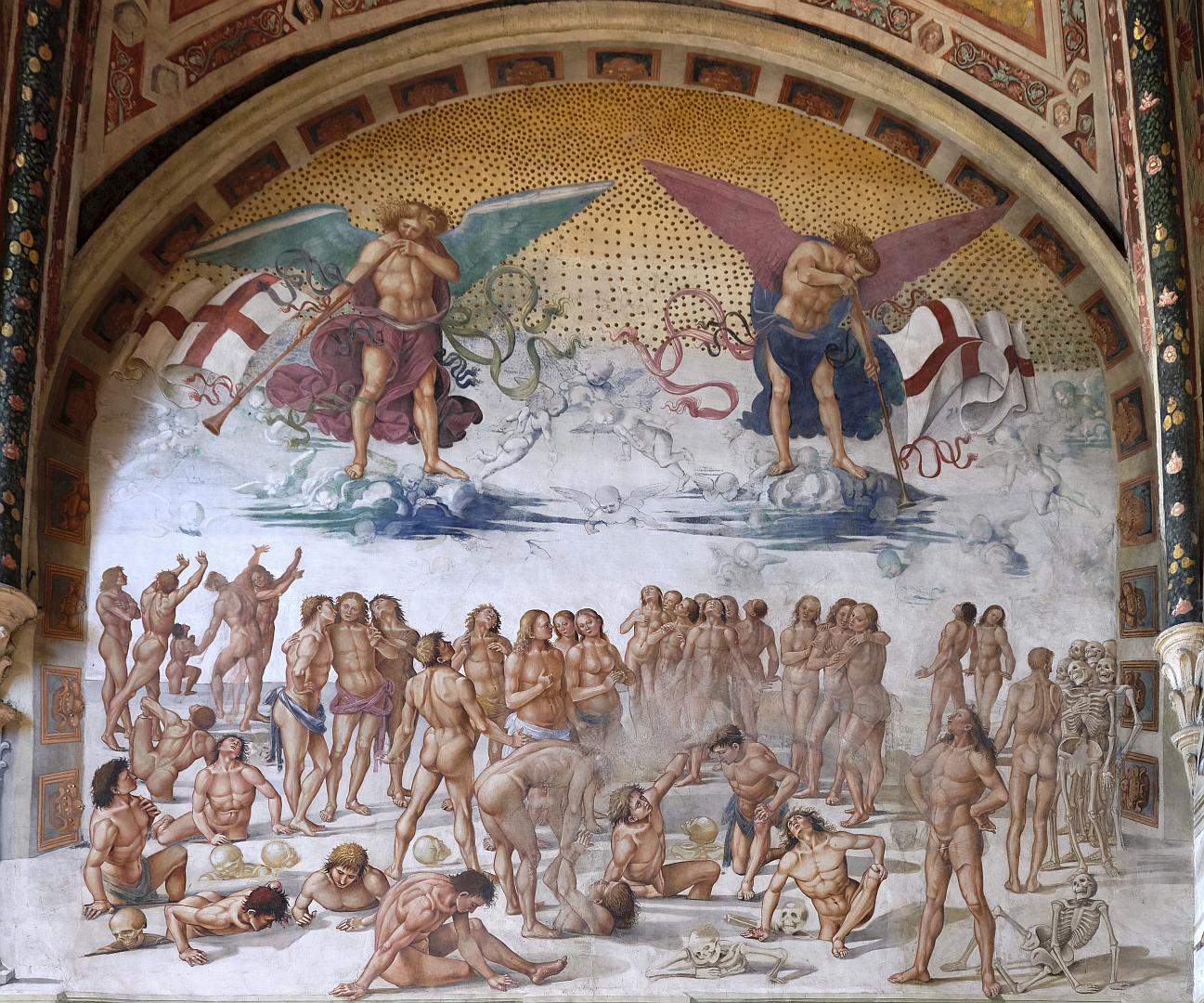

The Resurrection of the Flesh

In this scene the Last Trumpet is sounded, and the dead emerge from the earth – some already restored to flesh, others still as skeletons. I’m not sure why they did not all come back in complete form straight away.

Signorelli specialised in nude figures, in particular powerfully-muscled males, at a time when this was still a fairly novel thing in a sacred setting (as we have seen, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes came later). I’m not aware of whether the cathedral authorities thought he was being too daring.

The Damned in Hell

Signorelli definitely went to town on this scene. At the top right three armed archangels prevent any escape, while devils seize the damned souls and bear them into the fiery gate of hell at the lower left. There is a heaving mass of bodies below, but it is easy to distinguish the figures from each other – assisted, as one source points out, by the fact that Signorelli gives the devils grotesquely-coloured skin.

There is apparently a tradition that the naked woman being carried off on the back of a flying devil is a depiction of a former girlfriend of Signorelli’s who had jilted him. This would make it an early example of revenge porn, but I have not seen this in any serious discussion of the frescoes so it can probably be discounted.

The Elect in Paradise

The final large scene is a complete contrast to The Damned in Hell – obviously, because it is The Elect in Paradise. The raised dead stand around – most now decorously draped – while angels welcome them with crowns. More angels provide entertainment in the form of a chamber orchestra.

The Zoccoli

All of the main pictures start about two and a half metres above floor level. The walls beneath are painted to look like pedestals (Zoccoli in Italian), which gave Signorelli the opportunity for some more trompe l’oeil showing off. As we have already seen, he painted an apparent flat surface on top of the Zoccoli, which allowed some of the action to appear to spill forward out of the pictures. The Zoccoli are ornately decorated in the “grotesque” style, which in this context does not mean ugly but rather in a style based on the art seen in the ancient Roman ruins that were starting to be excavated. The classical theme is continued by the fact that in the centre of each Zoccolo there is a portrait, not of some saint or elder of the Church, but a poet.

By tradition these poets are Homer, Empedocles, Lucan, Horace, Ovid, Virgil and Dante, although some of these are now disputed. Dante is obvious, so no argument there. Ovid is surrounded by illustrations from his Metamorphoses, and Virgil with illustrations from his Georgics and Aeneid.

In medieval legend, the ancient poet Virgil acquired a second career as a magician and prophet. He therefore appears twice here, once in each persona – at least the wild-haired fellow below is thought to be him.

What they all have in common is that they wrote about visits to the underworld. Another feature that they share is that apart from Dante they are reacting to the apocalyptic events happening above them. They look at each other in alarm, or peer out of their little windows at the scenes above. It brings the biblical prophecies and classical literature together in a very Renaissance-humanist way, but it is also a little joke on Signorelli’s part.

Signorelli worked in Rome and elsewhere in central Italy, but I think this is his unquestioned masterpiece. It’s all quite an extraordinary experience, and one that we have yet to tire of repeating. When we first visited I was just impressed by the scale of it all. It was only later that I realised firstly how revolutionary it was in artistic terms, but also how elements of it would have resonated with recent history. We’ve been there a few times over the years, and Orvieto is one of our favourite places to take visitors. It helps that there is an excellent restaurant (Trattoria Vinosus) in the piazza next to the duomo.

A note on sources

These frescoes are an important landmark in Renaissance art, and the Duomo a major example of Gothic architecture, and as such you will find many references to them in art histories and online articles. There are references in Philip’s Travel Guides: Umbria by Jonathan Keats, which was particularly helpful in identifying which of the façade mosaics are later restorations. Much of what I have found on the frescoes comes from Signorelli’s Orvieto Frescoes, A Guide to the Cappella Nuova of Orvieto Cathedral, by Dugald McLellan, 1998. We bought our copy in Orvieto in 1999.

A note on the Photography

In some of the pictures of the Signorelli frescoes, I used a wide-angle lens from below, which introduced some distortion. I have attempted to correct the perspective in software, but only up to a point because of course some of the foreshortening was put there on purpose by Signorelli. If you want to get the full effect of his false-perspective tricks, you will just have to go there yourselves!

2 Replies to “The End of the World – The Duomo and Signorelli Frescoes in Orvieto”