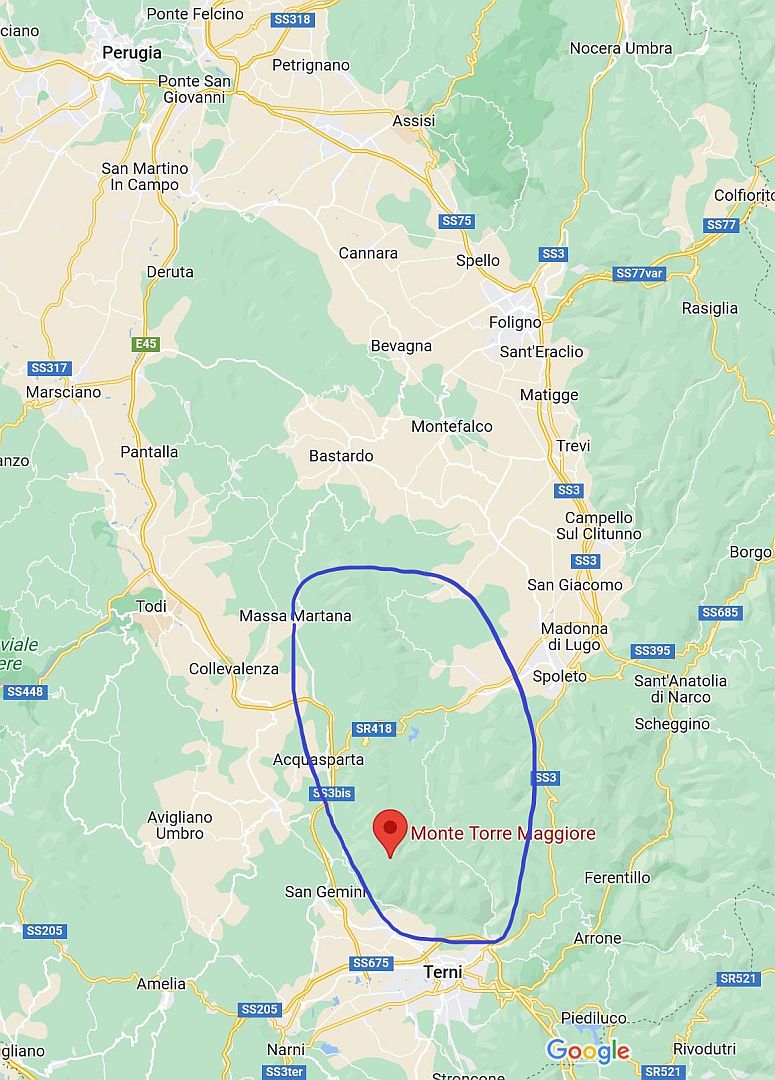

In Umbria, at the very top of Monte Torre Maggiore, is a site that was sacred for thousands of years. In June 2023 I resolved to make a trip there, as it was something I had had in mind for a while. Monte Torre Maggiore is the southernmost and highest peak in the chain called the Monti Martani which divides the Middle Tiber Valley from the Valle Umbra. Roughly speaking, the Middle Tiber Valley runs from Perugia in the north to Todi in the south, while the Valle Umbra runs from Assisi in the north to Spoleto in the south.

My desire to see the place came from reading a book titled simply Umbria by an English journalist called Patricia Clough, in which she describes heading up the mountain to the very summit, where she found the remains of a temple that dates from pre-Roman times. She makes much of how hard it was to find, and the difficulty of distinguishing it from some medieval remains a bit further down the mountain, but these days it is on Google Maps which solves both problems. “Pagan Sanctuary”, says Google – adding, a bit superfluously, “(ruin)”.

To get there one heads for a town called Cesi which is spectacularly located on a steep mountainside. It is however difficult to find a good spot from which to photograph Cesi, but if I ever get one I will update this post. Once in Cesi I turned off the car’s satnav and relied on Google Maps to find the road – which turned out to be steep, narrow, and in appalling condition even by the standards of Umbrian rural roads. Uncomfortably aware that my leased Peugeot didn’t have a spare tyre, just one of those silly repair kits, I crawled up the mountain in first gear, easing the car into and out of potholes when I couldn’t go round them. It took half an hour or so, and I only passed two cars. One, stationary in a clearing, had a couple of shifty-looking fellows in it who looked at me with suspicion. I decided they must be drug dealers. A bit later I passed a couple of lady carabiniere in one of their little green forestry patrol 4WD Fiat Pandas. The driver mouthed a friendly “buongiorno” to me as we passed, which I took to mean that what I was doing was neither illegal nor extremely foolish. Carabinieri carry military-grade weapons (they are in fact part of the military) so I assumed they would be a match for the drug dealers. In the event I saw nothing in the local online newspaper about a shootout on a lonely mountain road, so maybe I was wrong about them being drug dealers.

Sant’Erasmo

After having passed an astronomical observatory which appeared to be mothballed, about a third of the way up I reached a flat spot with somewhere to park, and got out. The scent of the wildflowers – of which there were many – was very strong. Big black shiny bumblebees, and little black insects with bright red wings, were feeding from them.

From the car park a ridge went out to a flat-topped outcrop, falling almost perpendicularly on three sides to the Terni valley a bit over two thousand feet below. On the flat top of the outcrop there is a church called Sant’Erasmo that dates from the 12th Century. It seemed unused but not abandoned, as there was a large padlock on the door.

Around Sant’Erasmo I saw various large stone blocks which looked ancient – from what I have been able to find out there was a settlement here called Clusiolum in Roman times, and in the early Middle Ages a Benedictine monastery for which Sant’Erasmo was presumably the church. Little remains of the Roman town, and nothing of the monastery as far as I could see, although doubtless much is hidden under the grass. In some places Sant’Erasmo is referred to not as a chiesa (church) but as an eremo (hermitage). There is a rather roughly-built stone extension out of the side of the church which doesn’t really fit any of the conventions of ecclesiastical architecture, so I speculate that might have been the hermit’s cell.

The view was tremendous, with a near-vertical slope down to the industrial outskirts of Terni on the left, and away to the right the town of Narni, sitting beside the gorge where the ancient military road (still called the Via Flaminia) heads down to Rome.

At the end of the ridge there are the remains of a medieval tower which would also have had a tremendous view. Presumably if the garrison saw an invading army they would have lit a fire or something. I didn’t go out to the tower, partly because it looked like a bit of a scramble, and partly because there were signs saying that it was both very dangerous and very illegal to approach within 15 metres.

Monte Torre Maggiore

Sant’Erasmo was very interesting, but not the object of the trip, so I climbed back in the car and kept going uphill. Shortly beyond Sant’Erasmo the road became unmetalled, and actually a lot smoother, so I made better progress. Eventually I got to where Google thought it would be a good idea to get out and continue on foot, so I found a place in which to park the car out of the hot sun, and did so. It was very steep. At first it was through woodland, then it came out onto a bare hillside with lots of white stones. It was hard going; the sun was quite fierce and the hillside continued to be steep. I was going very slowly and stopping frequently, and my smart watch kept asking if I had finished my workout. Given how hard I was gasping for air I found this rather insulting.

On another hill a couple of kilometres away members of a mountain rescue team were practising being winched up and down from a helicopter, so it wasn’t hugely peaceful. A large raptor circled overhead for a while then, presumably deciding that I wasn’t about to expire, headed away. After a while the helicopter left too, presumably deciding I didn’t need rescuing.

Eventually I got to the summit. The site is surrounded by a metal fence but there was no lock on the gate so I assumed it is just there to keep cattle out, and let myself in. It is on the highest point of the mountain so the view is indeed spectacular – almost 360 degrees from Assisi in the northeast to Todi in the northwest. To the southeast are the high Apennines of Abruzzo, range after range fading into the distance.

To the south, beyond a range of hills, are the plains of northern Lazio that lead down to Rome. Clough’s book says that locals claim that from here one could see the dome of St Peter’s in Rome on a clear day, and nowadays the tower blocks on the outskirts of Rome. That seems a bit plausible, but not in a summer heat haze.

As for the ruins themselves, they are the remains of two rectangular buildings. One has been dated to the 3rd Century BC, and a larger one from the 3rd or 4th Century AD, both erected over buried remains of a much earlier structure. There is also a smaller structure made of more haphazardly-arranged stones. I have no idea if that was part of the original or dates from some later period.

Being a good journalist rather than a cavalier blogger like me, Clough chased down the archaeologist who led the excavation of the site and who explained its pre-Roman origins. The excavations apparently revealed Bronze and Iron Age traces including ritual items in a grotto nearby, but to my untutored eye what remains above ground looks all Roman – large evenly-dressed stone blocks without mortar, fragments of fluted columns and the like.

It seems that as Rome’s dominions expanded to take in Umbria the site was redeveloped in Roman style. It is well-known that the Romans would co-opt local deities into their pantheon, so a shrine on some foggy British riverside or one on a baking Syrian hilltop would be rededicated to , for example, Jupiter plus the British name or Minerva plus the Syrian name. It could be that something similar happened here, or perhaps the original deity was just extinguished. Either way, the name of that original deity is lost now.

Given what we know, assimilation seems more characteristic of Roman practice and therefore more likely. It is seen as a strength of Roman imperialism – helping to encourage the locals into the new dominant culture, and presumably preventing local sacred sites from becoming centres of resistance.

In due course, something analogous happened with Christianity. It was not as explicit as pagan Roman syncretism, because the whole point of the Judeo-Christian god was that you were not allowed any other ones (although with the Trinity, the Virgin Mary, apostles, martyrs and other saints, in practice there was no shortage of additional subjects for veneration). What happened instead was that sacred sites continued to be co-opted, but the object was replacement rather than assimilation. Pagan temples were replaced by Christian churches on the same sites. Temples to Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, were frequently (or always? I don’t know) replaced by churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

That did not seem to have happened in the case of the temple on Monte Torre Maggiore. I haven’t seen any references to a Christian church on the site, and Clough’s archaeologist source suggests that the temples may have been violently destroyed. Whether that was part of the suppression of paganism, or was the result of war or earthquake, I do not know.

Sources

As I said, the inspiration for my visit to Monte Torre Maggiore, and the source for most of the information on the temple is Umbria by Patricia Clough, Haus Publishing, London, 2009. Although not a long book, it ranges across several aspects of living in Umbria, from history and culture to food and home renovation. I recommend it to anyone interested in the area.

I have found very little else – there is a brief mention of Sant’Erasmo in Cadogan Guides: Umbria (2009 edition), and nothing at all in the usually comprehensive Umbria, a Cultural Guide by Ian Campbell Ross. Online there are cursory mentions on a few tourism and outdoor walking sites, and only the stub of a Wikipedia page. It is an unusual experience for me to think that I might be making a substantial addition to the amount of online material on a subject.