An exhibition in Perugia, marking the 500th anniversary of the death of Perugino, Umbria’s most famous Renaissance artist, brings together paintings from all over the world.

We met the painter Perugino in my post on Tough Guys in Art – the Baglioni of Perugia. In that article I made the observation that he deserves to be more famous, and blamed the Tuscan chauvinism of the art historian Giorgio Vasari. Contemporary accounts certainly show him to have been held in very high regard, and no less a person than Isabella d’Este of Mantua, that most demanding of art patrons, worked very hard to get him to accept a commission, of which more later.

Of course the Umbrians are just as parochial as the Tuscans, and are very loyal to their boy – especially the Perugians. “Perugino” means “the guy from Perugia”, which isn’t quite true but he was from a town not far away and certainly spent a lot of time working in Perugia.

Perugino died in 1523, and to mark the occasion the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia has assembled an exhibition, not just from their own collection, but with works on loan from many other Italian galleries, as well as galleries in France, Britain and America.

The exhibition also features artists who were influenced by Perugino and developed the “Umbrian Style” further, such as Verrocchio, Ghirlandaio, Pinturicchio and Signorelli. And of course the most famous of Perugino’s pupils, Raphael.

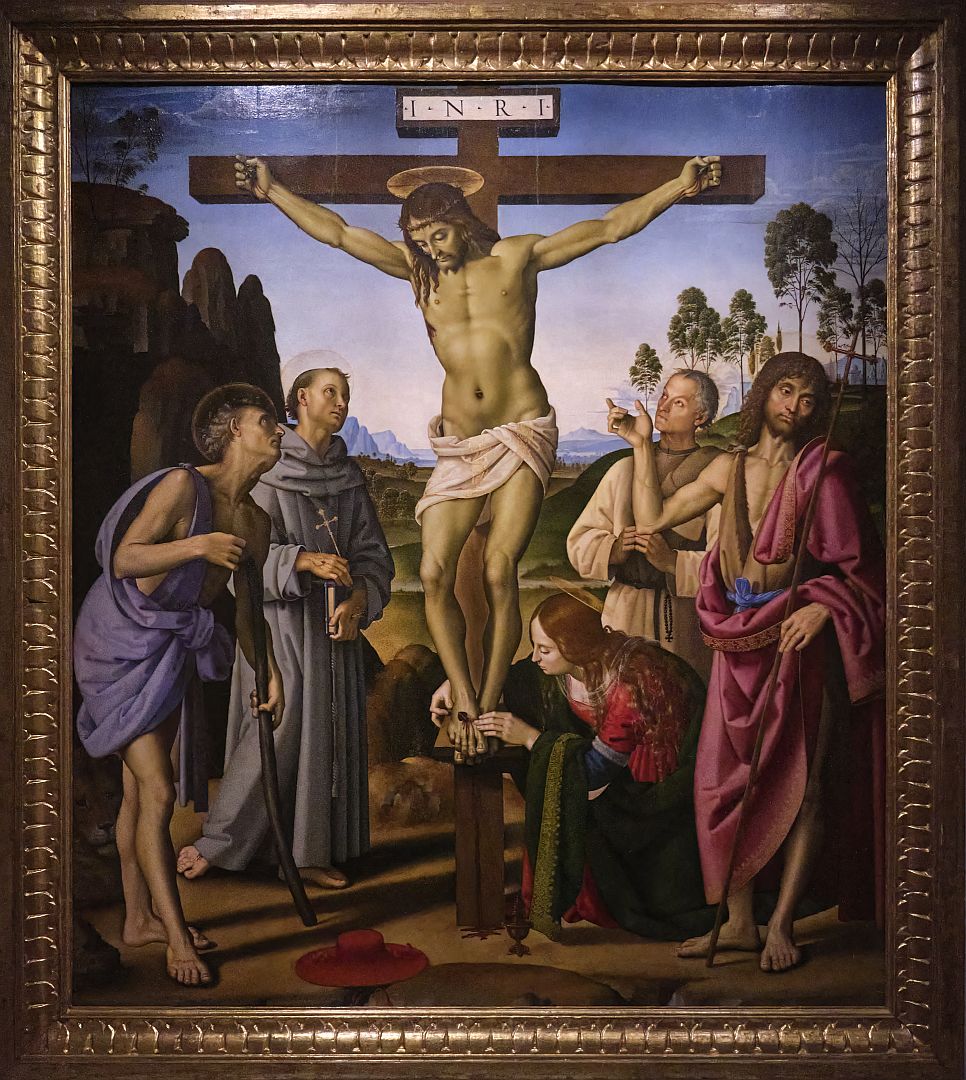

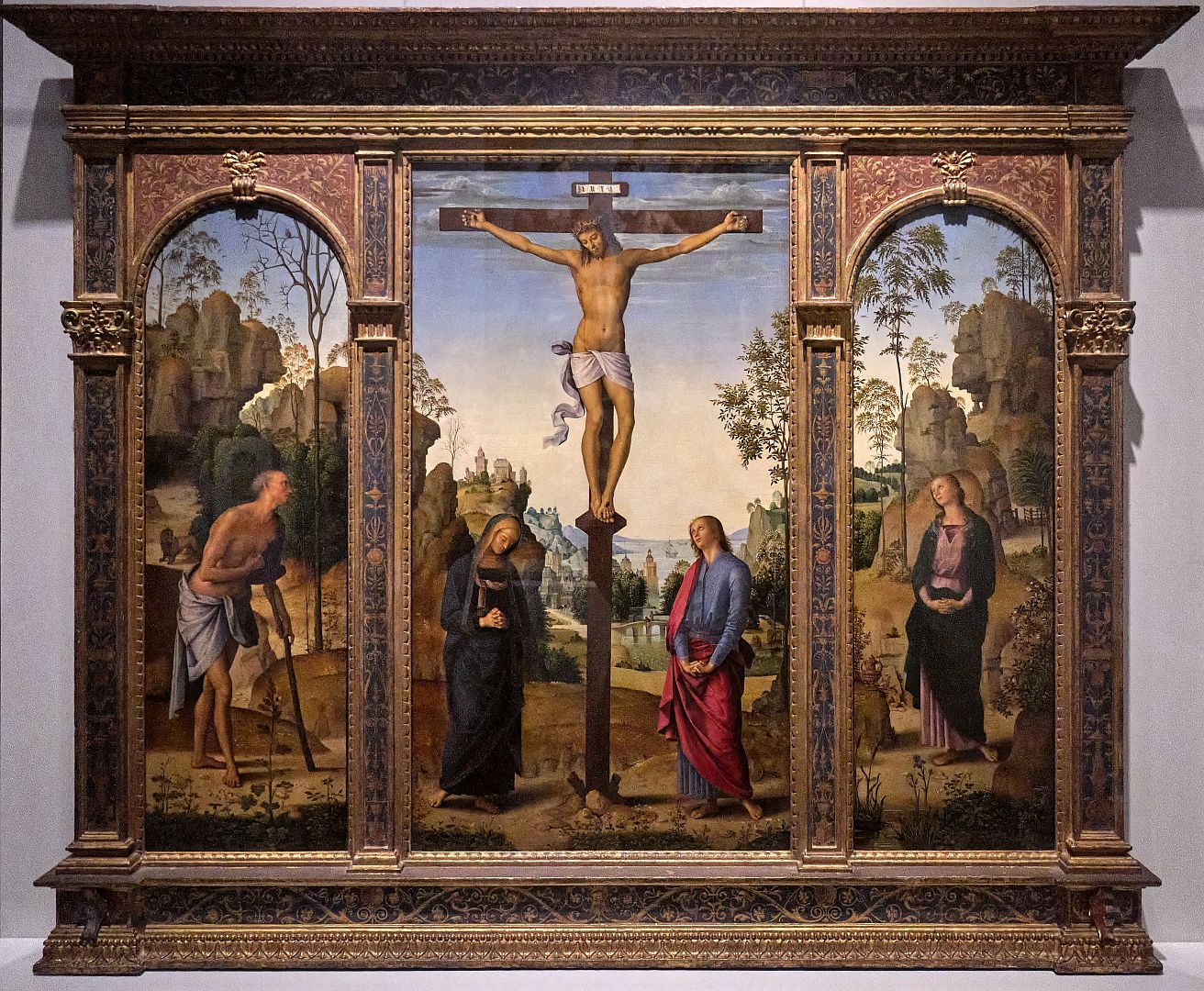

For me, the exhibition gave a somewhat different appreciation of Perugino’s work. This is because most Perugino works that one sees in Umbria are frescoes – paintings on fresh plaster just after it has been applied to a wall. But in this exhibition the loaned works are mostly oil paintings, or egg tempera. Painting in oils was a technique which Perugino was instrumental in introducing to Italy after its development in Flanders.

And therein lie a few insights (for me at least; I’m obviously not an art historian). Apart from the different materials, there are fundamental differences between fresco and oil. Firstly, the audience. Something that is fixed to the wall of a church is very much a public piece; obviously intended to generate reverence. Hence the beauty of Perugino’s frescoes, the clear pastel colours, the idyllic landscapes and the characters in stereotypical poses.

An oil painting, depending on the circumstances in which it is commissioned and displayed, can be less formulaic, more individualistic, more cerebral.

Even when using oils to paint devotional paintings, there is a difference. When painting frescoes, you have to work fast, before the plaster dries. An oil painting can be done more slowly with more consideration, and even altered halfway through if the painter changes his mind. To me, all this explains the fact that the oils in the exhibition show greater individuality, and better demonstrate just how good Perugino really was.

Furthermore – and rather prosaically – by definition an oil painting on canvas or wood is more portable than something painted directly onto a wall. This explains why an exhibition such as this is an unusual opportunity to appreciate the breadth of Perugino’s talent. Many of the finer works have been dispersed over the last five hundred years – either sold to wealthy collectors and then re-sold or donated to foreign galleries, or in the case of Napoleon, simply looted.

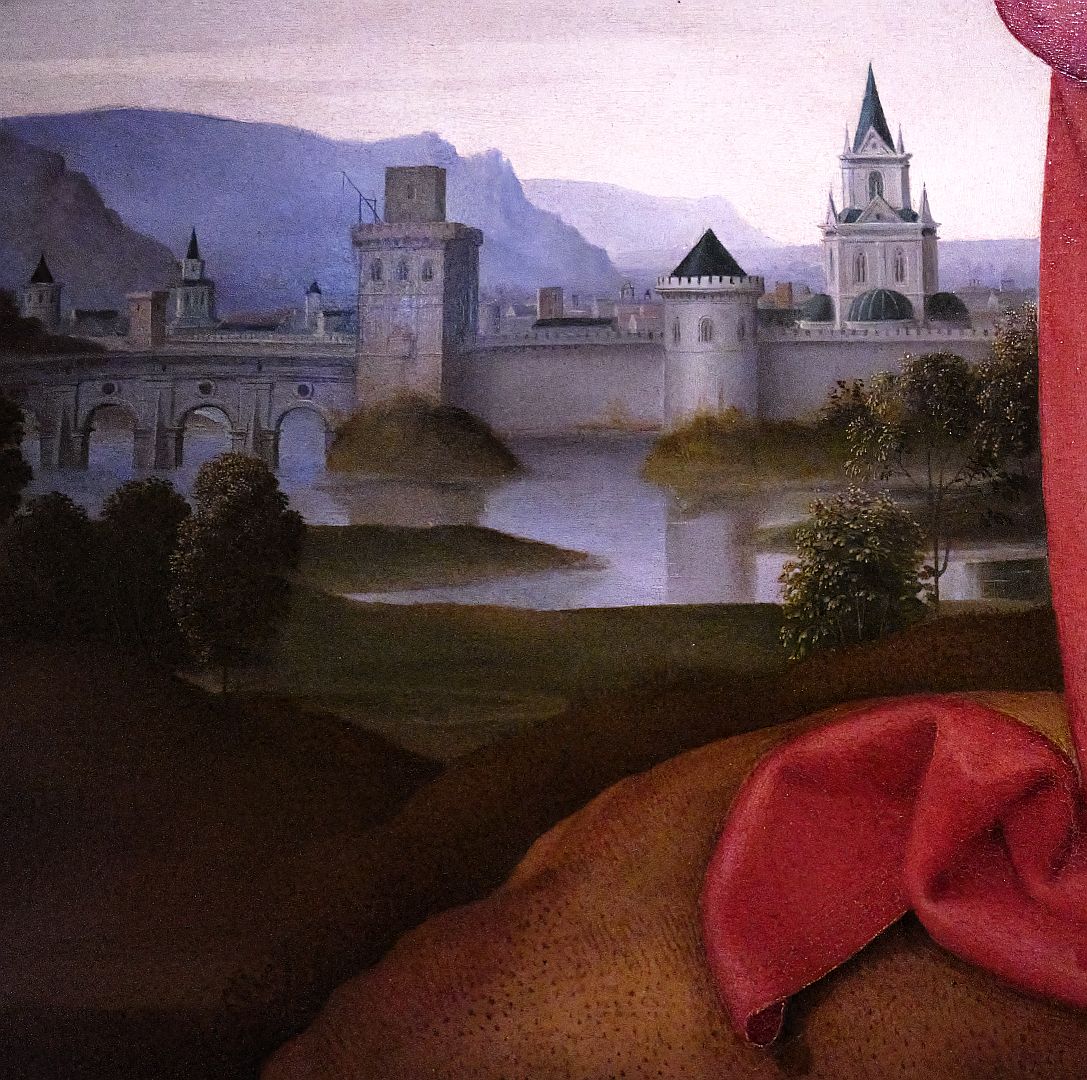

I love the background detail in many of Perugino’s paintings. The landscape in the Galitzin Triptych above is beautiful, as is the one in the Prayer in the Garden, below. There is also a lot of other business going on – on the left, Judas approaches with soldiers and priests, while more reinforcements arrive from the right. I’ve seen Perugino’s idea of Roman soldiers elsewhere, notably in a Martyrdom of St Sebastian in the town of Panicale above Lake Trasimeno. They are rather strange, but in a way the feathers and curly bits do actually remind me of some ancient Roman decorative illustrations.

One thing I learned is that Perugino’s later and uniformly beautiful Madonnas are supposedly all portraits of his own wife. If that is true he was a lucky fellow, but he would not have been the only Renaissance artist to marry one of his models. At least, unlike the wife of Filippo Lippi, Perugino’s wife wasn’t an absconded nun, as far as I know.

I mentioned Isabella d’Este earlier. She apparently pestered Perugino for ages for a painting. Eventually he agreed to a commission, then tried to explain missed deadlines with various poor excuses. Finally he produced something which is easily the weakest piece in the exhibition. The Lotta tra Amore e Castità (struggle between love and chastity) is a group of separate illustrations of stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses – just figures in a landscape with no visual unity. It was also painted in tempera (egg-based paint) rather than oils, so it lacks punch. Isabella was not pleased.

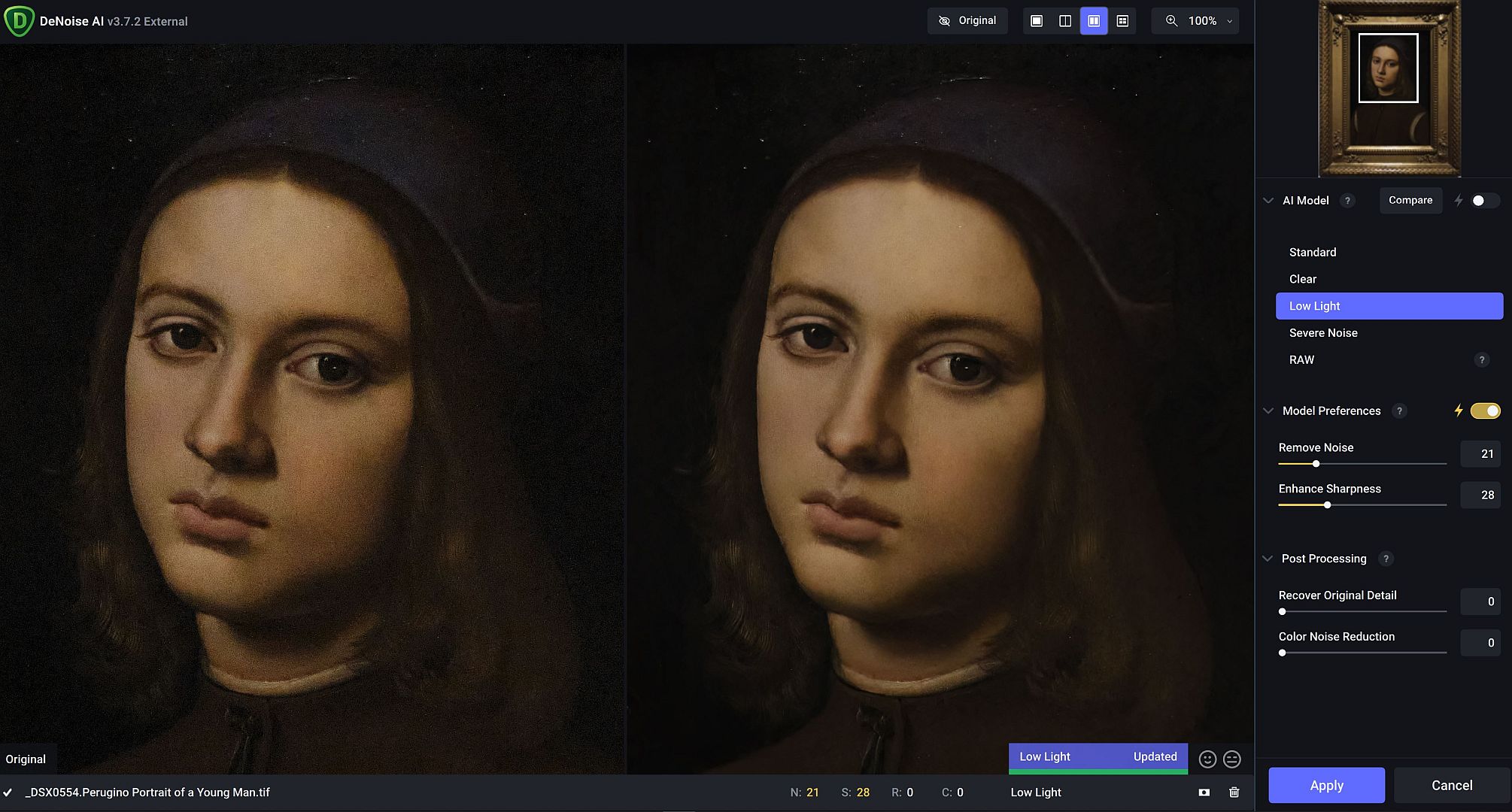

A note on the photography

As in many exhibitions, this one had very subdued lighting to protect the artworks. The appropriate way to photograph them would therefore be to set up a tripod and take long exposures; obviously that was not going to be permitted.

So I needed to use a hand-held camera and high ISO settings, which introduces digital noise. I was also using my small Fujifilm X-Pro3 camera, which while nice and light was a less suitable camera for the task than my medium-format Fujifilm GFX 50R would have been. Since noise in digital photography at high ISOs is partly random variations between one pixel and the next, a larger sensor equals smaller pixels relative to the size of the image, so noise is less obvious.

There were some workarounds available. I underexposed each shot by a few stops then applied exposure compensation later in Capture One software – I’m not sure how successful that was (edit: actually it was a bad idea). During post-processing I also used an external program called Topaz DeNoise AI which tries to smooth out the parts that should be smooth while retaining sharpness where sharpness is intended. Below is a screenshot showing a before and after comparison from that software.

Here is a link to the National Gallery of Umbria’s web page on the exhibition. I don’t know how long it will stay up after the exhibition closes though.