The city-state of Mantua, and its ruling family the Gonzaga, are the centre of a story of wars, politics, and art.

For some time now I’ve been contemplating a post on some aspect of the complex history of Mantua and Ferrara in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, their respective ducal families the Gonzaga and d’Este, and all the political, artistic and personal stories that swirl around those two cities. But it is such a big topic, and as with all big topics, it took me a while to think of how to start.

What a story it is though, with larger-than-life characters, heroes and villains, triumphs and tragedies. Other famous families have walk-on parts, including the Visconti and Sforza of Milan, the Montefeltro of Urbino, the Baglioni of Perugia and the most infamous family of the Renaissance, the Borgia.

The Context

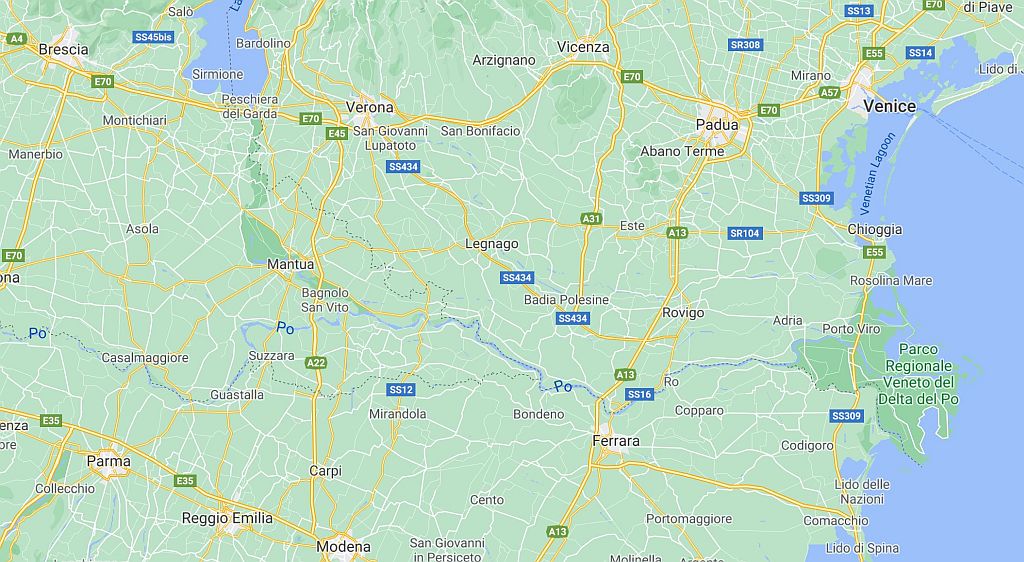

Let us start by quickly setting the context. Mantua and Ferrara are two cities in the flat eastern Po valley, about 60km apart.

In terms of modern regional boundaries, Mantua is in Veneto, and Ferrara is in Emilia-Romagna. Mantua (birthplace of the Ancient Roman poet Virgil) sits on a pair of lakes in the course of the Mincio, the river that drains Lake Garda and flows into the Po. Apparently Ferrara was once on the banks of the Po, but the river’s course altered after a medieval flood or earthquake and it now passes north of the city.

The flat land offers no particular advantages in terms of defence, although the marshy country would slow an army down a bit, and potentially infect its members with malaria and other fevers. The lakes on the northern side of Mantua would have assisted defenders to an extent. But the Po itself is no Rhine or Danube, and did not represent much of an obstacle to the movement of armies, especially in dry seasons.

Instead, the main strategic advantages of Mantua and Ferrara were geopolitics. From the Middle Ages onwards they found themselves in the border regions between more powerful states – Venice to the north and the Papacy to the south. To the west was Milan, and later, often, invading French armies. Other players included at first the German armies of the early Habsburg emperors, then the Spanish troops of their descendants.

The two cities took advantage of the strategic ambiguities of their borderland positions to play a game, lasting hundreds of years, to maintain their independence. As the major powers fought, the armies of Mantua and Ferrara were large enough, and their dukes generally had sufficient military skill, to tip the balance away from whichever was the stronger side at any given moment.

And they changed sides frequently. Usually these were commercial as well as political arrangements, and the income from mercenary activities as well as the surrounding rich agricultural land was sufficient to maintain armies as well as run magnificent courts (or the appearance thereof: Mantuan ducal jewels spent a lot of time in the care of Venetian moneylenders). Regular dynastic intermarriages between the two, and with other states like Milan and Urbino, reinforced the ties between them to the extent that when Mantua and Ferrara were on opposing sides, their employers never entirely trusted them not to connive together.

Mantua

We shall stay with Mantua for the rest of this post. The Gonzaga dynasty was long-lived, and the architecture associated with the family ranges from frowning medieval fortresses through elegant Renaissance palaces and pleasure pavilions, to exuberant mannerism.

The photograph of the ducal palace above shows an architectural innovation attributed to Palladio, where pairs of slim elegant columns take weight which would previously have required thick and solid single columns.

In addition to mercenary warfare, another lucrative business conducted by the Mantuan state was the breeding and sale of warhorses. Even Henry VIII of England sent an embassy to Mantua to acquire some. A field in the grounds of the ducal palace complex where these horses were exercised and displayed had an architectural surround built in the 1560s in the new “mannerist” style, which is pretty over-the-top.

So what about the paintings?

In the second half of the Fifteenth Century, ducal courts in Italy commissioned elaborately decorated rooms in their palaces. These were often semi-private rooms, where favoured guests would be invited to marvel at the wealth and good taste of the Duke, but also see pictures of members of the Ducal family in carefully-chosen settings, usually allegorical. A famous example is the chapel in the Medici Palace in Florence, decorated by Benozzo Gozzoli. In the cities of the Eastern Po Valley, one of the sought-after artists of the time was Andrea Mantegna, of whom more later.

One of the things that distinguished the artists of the Renaissance was their discovery of the mathematics of perspective. Once the initial novelty wore off, some started experimenting with vertical as well as horizontal perspective. It seems to have been more of a thing in the various cities of the Po Valley – or at least most examples I can recall come from there (although Goya did a famous one in Madrid).

As I’ve noted elsewhere, mythological subjects seen from below (especially Apollo and/or Phaeton) were popular as they were an excuse to show the rude bits.

As the Renaissance faded into the Baroque, one saw a few attempts to treat the ascension of Christ or the Virgin in the same way, although it was more of a challenge to do it decorously.

Mantegna and the Camera degli Sposi

Using increasing mastery of the mathematical theory of perspective to create realistic-looking paintings is known, unsurprisingly, as “Illusionist” art. It had a long run, up to the end of the 19th Century, but started in the early Renaissance. One of the better exponents during this first wave was Andrea Mantegna (c.1431-1506). Had he not made the mistake of not being from Tuscany, he would probably be better-known today. Instead he came from a place near Padua, and spent his early career in the Venetian Empire, before finally yielding to continuing offers from Ludovico III Gonzaga to move to Mantua in 1460 to become the court painter.

Despite Mantegna being famously difficult to deal with (getting even grumpier as he grew older) three generations of Gonzaga rulers treated him with great respect and generosity, granting him a remarkably large salary and in due course a knighthood.

Mantegna was required to turn his hand to many things, but his principal job was to decorate, and redecorate, the ducal palace. His acknowledged masterpiece is the so-called Camera degli Sposi (“Bridal Chamber”). Despite its name, it is unlikely to have been a private bedroom – the Gonzaga were too practical to waste expensive art on something that would not be seen by others. Instead it would have been a semi-public room into which important guests would be invited for audiences, to note the luxury in which the family lived in their supposedly private apartments, and to draw conclusions about their wealth and power. Such were the games that were played, and the illusions were created not just on the walls and ceilings, but in people’s minds.

On the walls of the room are very carefully-composed paintings of Ludovico and the Gonzaga family, replete with coded messages about the status of the family. In the “Greeting Scene”, Ludovico and his family (and their dog) are greeting their second son Francesco, who, after much expense and diplomatic effort by the family, had just been made a cardinal when Mantua had hosted a council presided over by Pope Pius II. Also in the picture are the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III, and the King of Denmark, Christian I. Although no such meeting with these foreign monarchs ever took place, the message is clear – you are being told that the Gonzaga are the equals of such rulers. Almost as eloquent are the omissions – no penny ha’penny Italian warlords such as the Sforza of Milan (actually Ludovico’s employers at the time!) merit inclusion. In the background is an idealised ancient city which looks nothing like flat Mantua amid its swamps.

In the “Court Scene”, Ludovico, surrounded by his family, is shown in the process of ruling, turning aside as a secretary whispers in his ear, no doubt something to do with the piece of paper in his hand. Courtiers await their turn for an audience. The scene is located above a fireplace, higher on the wall than the Meeting Scene, and Mantegna has emphasised that with a from-below perspective, which emphasises that the viewer is both actually and figuratively at a lower level.

All very imposing, not to say pompous. But look up. On the ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi is something that is, in its whimsicality and intimacy, completely different from the didacticism of the wall paintings. And the mastery of technique Mantegna shows here is greater than anywhere else in the room. The painting represents an “oculus” open to the sky. Courtiers lean over the balustrade, and rather than ignoring you, as in the other paintings, here they are looking straight at you and sharing a joke (or perhaps planning a practical joke on you). It seems that the old curmudgeon had a playful side after all.

I have followed convention in referring to Mantua as a duchy, and the palace complex as the “Ducal Palace”. In fact Ludovico was only a Marquis – his grandson Federico became the 1st Duke of Mantua in 1500.

If the title “Duke of Mantua” has sinister overtones to you, it may be because a Duke of Mantua is the cruel and licentious villain in Verdi’s Rigoletto. True to Italian form, you can buy a cold drink or a souvenir in the “House of Rigoletto” across the piazza from the Ducal Palace, and look at the statue of the tragic jester in its grounds. It’s all completely bogus though. The play on which the opera is based was Victor Hugo’s Le Roi s’Amuse. But the opera had been commissioned by the La Fenice opera house in Venice, then under Austrian rule, and the Austrian censors frowned on depicting a monarch as the villain, so the libretto was rewritten to pin the rap on the – by then extinct – House of Mantua. It’s a bit unfair on the Gonzaga, although the last couple of dukes sound as if they would have been up for it.

Now that I’ve finally started, I’ll have more to say on Mantua and Ferrara in due course.

Historical Sources

Any decent history of Italy in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance should give an overview of the Gonzaga, their wars and politics. One book which is only about them is A Renaissance Tapestry – The Gonzaga of Mantua (London 1988) by the New York writer Kate Simon. Given the complexity and length of the story, it contains that most useful of visual aids – an extensive family tree. Simon made her name as a travel writer, so she has an easy, readable style, but it is firmly grounded in scholarship. It was one of her last published works (she died in 1990).

A note on the Photography

As I have said elsewhere, the best way to take interior photographs of art and architecture is to mount the camera tripod on a platform at the same height as the subject, and illuminate it with bright, even, colour-neutral lighting. When you haven’t been employed to take the photographs, but have paid your 10 euros and are milling around at floor level with the other tourists, wishing that the bloke in the floral shirt and bermuda shorts would get out of the way, one is forced to compromise.

Digital post-processing helps a lot, allowing perspective correction to fix the “leaning backwards” effect caused by photographing from below, and correcting the colour cast caused by tungsten or fluorescent lighting. I have done both of these on the interior shots above, using Hasselblad Phocus software and Photoshop. Unfortunately sometimes the light sources are mixed. In the Court Scene, a shaft of natural light comes in from the bottom left. When I corrected for the predominant yellow tungsten light, the natural light turned blue.

I didn’t correct all of the from-below perspective in the Court Scene, because it was put there on purpose by Mantegna!

Fascinating, thank you.