Returning to the theme of Paleochristian churches, we visit Trastevere, one of Rome’s trendiest districts, to see two churches that have been there since the third and fourth centuries, although it must be admitted that you have to look quite hard to see the older parts.

Trastevere

“Trastevere” (the stress is on the second syllable) is the Italianisation of its ancient Latin name, Trans Tiberim, which simply means, rather prosaically, “across the Tiber”. Being on the western side of the Tiber, in Rome’s earliest days it was actually in Etruscan territory. As Rome grew, fishermen and immigrants settled there, until under Augustus it formally became part of the city. At around this time wealthy Romans built luxurious villas beside the Tiber – we saw artefacts from some of these in the article on The Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme.

In the 3rd Century Trastevere was enclosed within the Aurelian Walls, which marked the ancient city’s greatest extent. Devastated in the barbarian invasions, in medieval times it again became the home of the poor and the fringe dwellers – including Rome’s Jewish population, until they were moved across the river to the new ghetto. The cycle began again in the Renaissance when wealthy families like the Farnese built villas there.

These days Trastevere is one of the most popular areas of Rome with both locals and visitors. It has a bohemian feel and its bars, trattorie and restaurants seem uncountable, although it also has some quiet back streets. On any evening it is full of cheerful crowds.

Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

In a garden shady this holy lady

With reverent cadence and subtle psalm

Like a black swan as death came on

Poured forth her song in perfect calm

W.H.Auden, text to “Hymn to Saint Cecilia” by Benjamin Britten

My childhood religious education was not big on saints, so my first encounter with St Cecilia was through music, in her capacity as patron saint thereof. As such, composers from Henry Purcell and Alessandro Scarlatti[1] to Benjamin Britten have written pieces dedicated to her, but that being said, I have to say that the justification for awarding her that particular portfolio seems a bit slim: the story goes that at her wedding she disdained the musicians playing live, preferring to sing silently to God in her heart. That doesn’t really make her sound like a music lover to me, unless the band was particularly bad (we’ve been to weddings like that). Anyway, she went on to convert her husband Valerian to Christianity, they both remained chaste virgins, and in due course both were martyred. There has been a church on the site of her house since the 3rd Century.

There is of course another possibility. We saw in the article on Santa Sabina that the Basilica of Santa Sabina on the Aventine Hill may be called that because it was built on land donated by a wealthy Roman lady called Sabina, and that over time “Sabina’s Church” became “Saint Sabina’s Church”, necessitating the invention of a hagiography for an apocryphal saint. It seems that there is a possibility that something similar may have happened here – that a wealthy lady named Cecilia donated her land in Trans Tiberim for the founding of a church. Between the founding of the 3rd-Century church and its rebuilding by Pope Paschal I in 822 came several centuries of war, destruction, societal collapse and poor record-keeping, and over time “Cecilia’s Church” may have become “Saint Cecilia’s Church” in popular memory.

Or maybe she founded the church and was then martyred; the two versions are not entirely incompatible. Whatever really happened, the remains of a 1st-Century Roman house have been found under the church, and however her story may have evolved since, there seems no reason not to think that there was a Roman lady called Cecilia, who became a Christian, and who lived here. That’s good enough for me, whether she actually liked music or not.

When you approach the church, you would be forgiven for thinking that you were in the wrong place and there is no church there at all. Instead there is what looks like an office building from the 18th Century, dedicated not, it would appear, to the saint, but to the cardinal who commissioned it, one Francesco Acquaviva d’Aragona.

The building turns out to be a kind of gatehouse, and passing through it you find yourself in a pretty courtyard, at the end of which is the church. The initial impression is again baroque, and again the most important dedicatee appears to be Cardinal Acquaviva, who had the church redecorated in 1725. But behind is a campanile from the 12th Century, and above the columns supporting the portico are mosaics which, although presumably 18th Century as well, do a reasonable job of replicating the style of early churches. I have not been able to find out whether they are based on something that had been there before, but it would not surprise me if they were.

Inside, it is all still very baroque. You have to go all the way down to the altar to see the apse mosaic from the 800s. If you remember the article which included a description of the church of Santa Prassede, you might find this one a bit familiar. Both were rebuilt by Pope Paschal I, and as in Santa Prassede, Paschal has not just placed his monogram over the apse but has included himself in the mosaic.

That’s him on the left, with the conventional square halo given to someone who was still living at the time of the portrait. He’s holding a model of the church which he is presenting to Saint Cecilia, who has her arm round his shoulder in a very friendly way. Either side of Christ are Saints Peter and Paul, and on the other side from Paschal and Cecilia are two saints who are apparently Valerian – Cecilia’s husband – and Saint Agatha of Sicily.

Under the ciborium is a glass case containing a sculpture of the uncorrupted body of the saint as it was said to have appeared when her tomb was opened in 1599. However the supposed remains of the saint were only placed in the church during Paschal’s rebuilding, six hundred years after her martyrdom, so there is some room for doubt.

There’s not much left to excite the paleophile. There’s a 14th-Century fresco which good old Cardinal Acquaviva had whitewashed over. It has since been restored, but you need to make special arrangements with the neighbouring nuns to see it. Nonetheless as amateur musicians paying respect to a patron saint who probably existed, and may or may not have liked music, we were glad to have visited. And also, while lots of things in Rome are old, here is a spot where one can feel fairly confident that at least some aspects of the story have a basis in the historical fact of an ordinary person who lived here 17 centuries ago.

So let’s move on.

Santa Maria in Trastevere

Heading north from Santa Cecilia one passes into the trendiest bits of Trastevere and ends up in the Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere, in front of the church of the same name.

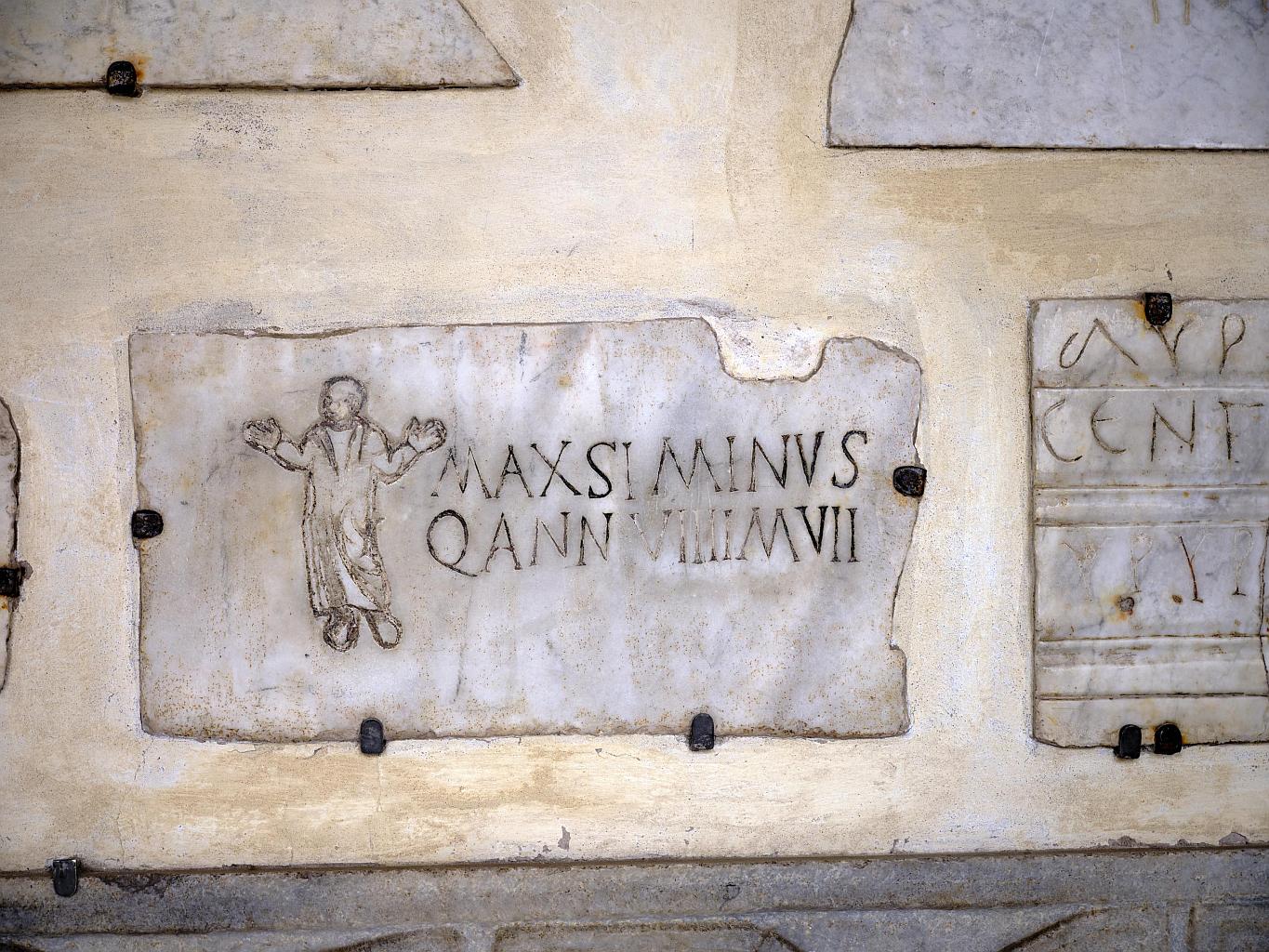

The first church here was founded in the 200s, on the site of a retirement home for Roman soldiers. Some claim it to have been the first church dedicated to the Virgin Mary, although I believe that honour is more conventionally given to Santa Maria Maggiore. Inside the portico you will see that the walls are lined with a good many ancient inscriptions, most of which appear to be funerary.

Above the portico is a 13th-Century mosaic depicting the Madonna and Child suckling, flanked by female saints.

Entering the interior you step back nine hundred years earlier than the exterior mosaics, with the floor plan and the walls dating back to the 340s. Even though there are a lot of later additions, it is not too hard to get an impression of what it might have been like in the 4th Century.

If you look at the columns that line the nave you will note that they are of different heights. They were scavenged from the ruins of the Baths of Caracalla, and have been evened up by the use of different sized capitals.

Some of the capitals were originally decorated with faces which scholars in the 19th Century identified as being various pagan deities. When the arch-conservative Pope Pius IX heard about it, he had the faces chiselled off.

In the apse vault is a 12th-Century mosaic of The Crowning of the Virgin, which includes the Pope of the day (Innocent II) holding a model of the church – its most significant rebuilding occurred during his reign.

So far, apart from the columns, there is not a lot that merits the “paleochristian” label. There is an 8th-Century icon of the Virgin in a side chapel but alas it was too dark for me to take a photograph.

However I had read that in the sacristy there could be seen some mosaics from the 1st Century, perhaps from the old soldiers’ home that was previously on the site. There was a chap in a cassock bustling about arranging things in the nave so I approached him and asked about them. He (maybe he was the sacristan) was very obliging and let me into the sacristy, saying only that I should shut the door behind me when I was finished.

[1] Alessandro Scarlatti’s “Saint Cecilia Mass”, only rediscovered in the 1960s, is a real cracker. It was dedicated to Cardinal Acquaviva, mentioned above, however its first performance was not here but in Santa Maria Maggiore in 1720.