In 2019 I wrote a post called The Garden of Livia Drusilla in which I described a visit to the Museum of Palazzo Massimo alle Terme in Rome. It is a museum that we think is well worth one’s time. It isn’t right at the top of the charts like the Capitoline Museum, the Borghese Gallery or the Villa Farnesina, so it is usually not too crowded, and it is close to Termini station, thus easy to get to. The palazzo is a large 19th-Century building built on the pattern of a 16th-Century Renaissance palace, and the terme from which the palazzo gets its name are the Baths of Diocletian, close nearby.

Everything in the Palazzo Massimo is from ancient Rome. That 2019 article put particular emphasis on the amazing frescoes recovered from the villa of the Empress Livia, wife of Augustus (and villainess of Robert Graves’s novel I Claudius). To me those frescoes are still the main reason to visit, but in hindsight I was a bit jaded in my attitude to the rest of the museum, partly because of what one might call “gallery fatigue” (a common affliction among visitors to Rome) and also because the place was overrun with bored schoolchildren.

Recently we paid a return visit and I found myself in a much more receptive mood. It was August and all the kids were at the beach. And museums and galleries are mostly air-conditioned; an encouragement to cultural virtue in hot weather if ever there was one. Instead of reflecting on how all the marble busts start to look the same after a while, this time we noticed the differences between the styles of different eras, and between realistic busts done from life compared with mass-produced figures of emperors and empresses.

It was also interesting to see the changes in fashion. It is curious and – to the history nerd – somewhat irritating that people seem to think the ancient Romans never changed the way they looked. In art and cinema, Roman clothing, armour, weapons and so forth look the same whatever the period. From the oath of the Horatii in pre-Republican days, through to the Punic Wars, the Caesars and the fall of the empire in the 5th Century AD, everyone dresses like Augustus and Livia, senators wear togas and the soldiers wear helmets and armour like those on Trajan’s column. But this is a period of six or seven hundred years – it is as if we in the 21st Century were all still wearing Elizabethan ruffs around our necks, and our military were wearing steel breastplates and carrying pikes.

A good museum, with informative labels on the exhibits, can go a long way to dispel the impression that Rome never changed. Given that most of the realistic statues in the museum are busts, the most obvious indicators of changing fashions are hairstyles, and the presence or absence of beards for men.

The Nemi Ships

One very impressive section contains remarkably preserved bronze fittings from the “Nemi Ships”. Nemi is a small volcanic lake southeast of Rome, sacred in antiquity, where the Emperor Caligula had two large and luxurious ships built. They seem to have been partly for religious ceremonies but also, like modern superyachts, they were symbols of great wealth and power. After Caligula’s assassination the ships were deliberately overloaded with rocks and sunk, presumably on the orders of Claudius. They were recovered in the 1930s after the Italian Navy temporarily drained the lake, and housed in a purpose-built museum. Alas they were destroyed by fire in 1944 (either as a result of Allied artillery or German sabotage; opinions vary). Fortunately several of the bronze pieces survived and are now housed in the Palazzo Massimo.

The relics of the Nemi ships are in amazing condition and show extraordinary workmanship, as you might expect when Caligula was the customer. No doubt the penalty clauses in the contract were severe.

The Frescoes and Mosaics

For us, the main attractions of the museum are the frescoes and mosaics, which I covered in my first post. These are wall and floor decorations recovered from several ancient villas in and around Rome, and in some cases displayed in spaces that are the same size as the original rooms. It does give you a bit of an idea of what it would have been like to be in one of those brightly-coloured rooms.

I don’t propose to duplicate material from that earlier post, especially the frescoes from Livia’s villa. But here are some additional pictures. The dark frescoes are apparently from a dining room, where the black colouring would not show smoke stains from the fires used to warm the food.

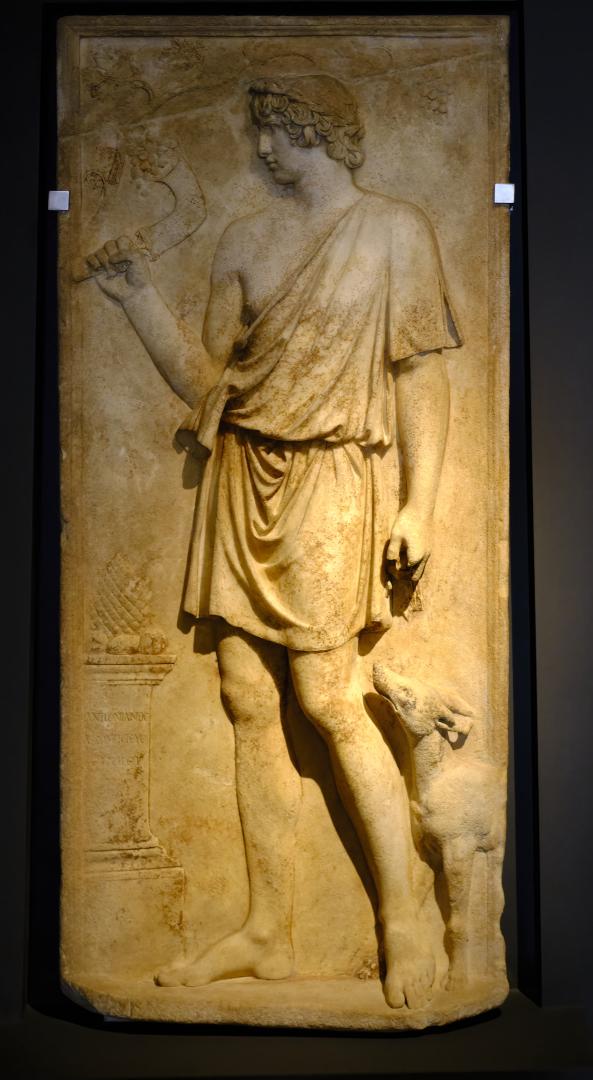

Greek stuff

It is well-known that the ancient Romans looked up to the Greeks culturally, and had a bit of an inferiority complex about them, even after having incorporated them into the empire. After all, it was from Magna Graecia (the Greek colonies in southern Italy and Sicily) that the Romans, when still a bunch of cattle thieves in their huts by the Tiber, were first exposed to advanced art and philosophy. Conventionally they also adopted the Greek pantheon as well, but I suppose we will never know the extent to which the Olympian gods matched the already-existing local Latin deities (my guess is, probably a lot: there’s nothing particularly novel in having a God of War, a Goddess of Love and so on).

Many of the more expensive bronze statues found in Italy are the product of Greek workshops, and we know that because some of the most spectacular survivals have been dredged up from the wrecks of the ships on which they were being imported.

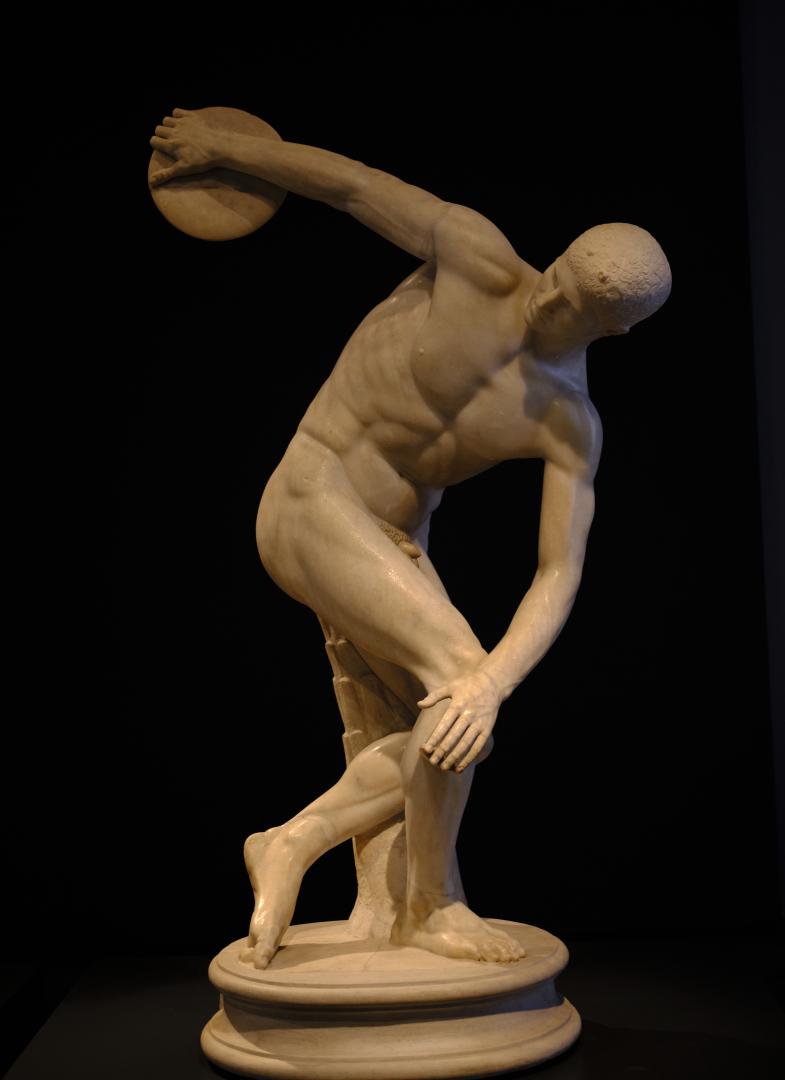

Presumably most of the cheaper marble statues copied from Greek originals came from local Italian workshops, including the many copies of the diskobòlos (discus thrower), originally in bronze by the sculptor Myron in around 450 BC. Given the number of copies that have been found, it was obviously a top seller, which is fortunate as the original is lost. Like modern copies of Michelangelo’s David, the diskobòloi came in varying sizes and qualities.

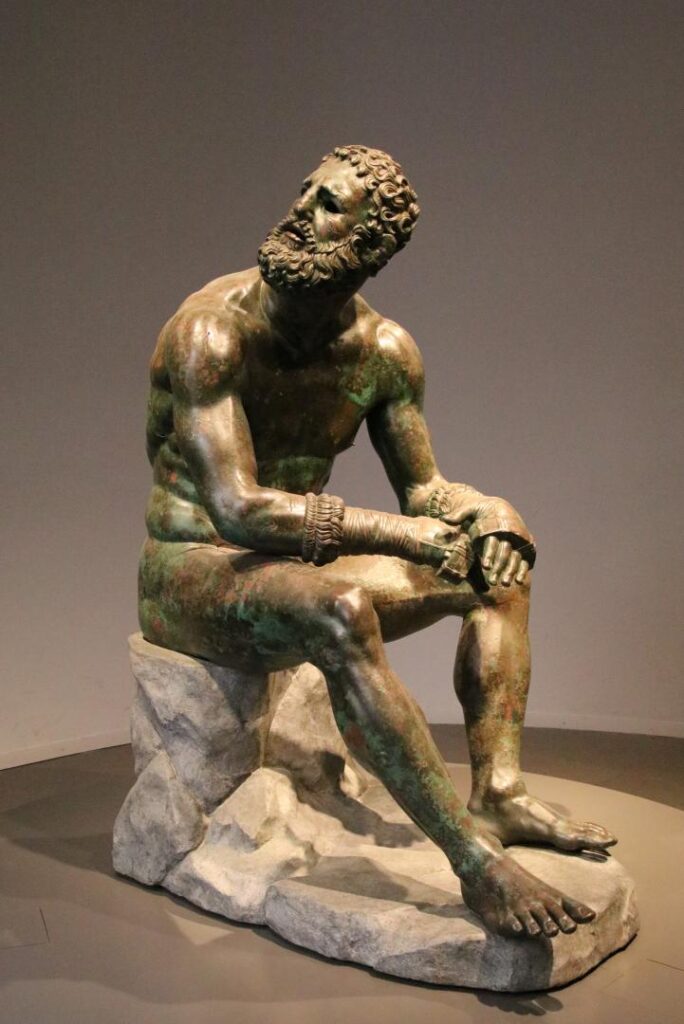

The bronze statues were made using the “lost wax” technique, where the original was sculpted in wax, then encased in clay. The clay was heated, the wax melted and drained out, and the resulting clay mould could be used to cast the final bronze.

There are two extraordinary examples of such bronze statues in the Palazzo Massimo, both apparently of Greek manufacture. Both were excavated on the slopes of Rome’s Quirinal Hill in 1885, and it is thought that they would have originally decorated the nearby Baths of Constantine. They appeared to have been deliberately buried to safeguard them, perhaps during the Gothic sack of Rome in 410 AD. Burying them turns out to have been a good idea – going undiscovered for so long almost certainly preserved them, because in the Middle Ages and even the Renaissance, Popes tended to order rediscovered ancient bronze statues to be melted down for re-use in religious art or even cannon.

We are used to seeing such bronze statues with empty eyes, but this is misleading. The originals had realistic-looking eyes made from coloured stone.

The first statue is known by art historians as the “Hellenistic Prince”, and it is not known who it is intended to be. It might be an actual ruler of one of the Hellenistic kingdoms (that is, the states founded by the generals of Alexander the Great after Alexander’s death). Or it might be a depiction of a Roman emperor, but so highly idealised that the identity of the subject eludes us. Either way, there is a great deal of character in the depiction.

But in terms of sheer humanity that speaks to us across the centuries, the Hellenistic Prince comes a long way second to the “Resting Boxer”.

The boxer is seated after a fight, bleeding from wounds (picked out in copper) and clearly exhausted. He bears the scars of many bouts, one of which broke his nose, and others which left him with cauliflower ears.

This would have been a great work in any era, but – for it was probably made between 350 and 50 BC – it is very special to see something that is so very old yet has such emotional force for us today. I found myself humming The Boxer by Paul Simon.

“In the clearing stands a boxer and a fighter by his trade, and he carries the reminders of every glove that laid him down or cut him till he cried out in his anger and his shame, ‘I am leaving, I am leaving,’ but the fighter still remains.”

A statue from 350 BC and a song from 1969 AD, and the same emotional reaction.

People talk and write a lot of nonsense about art, and what it is for. My view is simple, and not particularly fashionable. When I see a work like this, or one of the mosaics in Monreale, or I listen to a piece of music by Monteverdi, I am experiencing an emotional response which to varying degrees is not unlike what someone long dead might have felt under the same circumstances.

Great art reminds you what it is to be human.

3 Replies to “Palazzo Massimo alle Terme in Rome”