Avignon is a town in southern France. Why are we talking about it on a site about Italian history? Thank you; I’m glad you asked.

If you read my post last year about Abruzzo and the Reluctant Pope, you might recall that after the resignation of the unfortunate Pope Celestine V in 1294, the Papacy fell into the hands of Cardinal Benedetto Caetani, who took the name Boniface VIII. Celestine and Boniface were as unlike each other as two popes possibly could be: where Celestine had been an unlettered hermit, Boniface was a legal scholar who codified canon law, founded Rome University, and re-established the Vatican Library. Where Celestine had been simple, pious and meek, Boniface was ambitious, proud and quick to anger. Where Celestine had worn rags, slept in a cell and been uninterested in the affairs of the world, Boniface was keen to enrich himself and his family, and above all was determined to re-assert the secular political power of the papacy over the emerging unitary states of Europe, particularly France. Trouble was brewing.

Another article I posted last year was Viterbo – Wet Bishops in the Papal Palace. In that I talked about how a conclave to elect a new pope was deadlocked for two years in 1269-71, because all the French bishops were under orders to vote only for a Frenchman, and all the other bishops were determined to have anyone but a Frenchman. The town authorities in Viterbo, where the conclave was taking place, were obliged to take drastic measures to try and break the deadlock. That was about thirty years before Boniface.

Boniface’s papacy was to be overshadowed by increasing hostility between Rome and the King of France, Philip IV (“the Fair”). Philip was planning a war with England, and thought that it would be a good idea to finance it by taxing church property. Not surprisingly, Boniface thought this was a rotten idea, and issued a Bull forbidding such taxation without permission from Rome. Philip responded by barring the entry into France of papal tax collectors, Boniface fired off another Bull, and things quickly got out of control.

Philip accused Boniface of all sorts of crimes and dispatched troops into Italy to capture him, and bring him back to France to face trial in front of a General Council of the Church. These troops were accompanied by Italian mercenaries led by members of the Colonna family – one of the strongest families in Rome, whom Boniface had unwisely and unnecessarily antagonised. Boniface confronted the invaders and was briefly taken captive and beaten before being rescued by the Orsini family, the traditional rivals of the Colonna. But he was old by then and it was all too much. He did the only thing he could to reduce the tension of the situation, which was to die. Dante passed judgement on recent events by placing both Celestine and Boniface in Hell, which was a bit unfair on Celestine.

Boniface’s successor need not detain us long, because he didn’t bother anyone for very long, lasting less than a year.

So there we were again in another deadlocked conclave, again meeting in Perugia, and which went on for eleven months without resolution. Since Gregory X’s reforms to the election process after the debacle of Viterbo, only cardinals could take part, but none of them could gather enough votes from the others. Eventually, having rejected everyone in the College of Cardinals, they again decided to pick someone from outside, and their choice fell on Bertrand de Got, Bishop of Bordeaux, and yes, a Frenchman.

Bertrand, who took the name of Clement V, could have been a strong and effective pope, had he been Italian. As John Julius Norwich writes, “Although a shameless nepotist, the new Pope was a distinguished canon lawyer and an efficient administrator. He concentrated on the missionary role of the Church, going so far as to establish chairs in Arabic and other oriental languages at Paris, Oxford, Bologna and Salamanca.”

But he wasn’t Italian; he was French, and a subject of Philip IV. Norwich goes on to say that from the moment of his election, he found himself under almost intolerable pressure from his master, King Philip, who insisted that he be crowned in France, and afterwards insisted he remain there.

For a while Clement and his cardinals moved from place to place in France, then in 1309 Clement decided to settle the court in Avignon, which was not technically part of the kingdom of France. The eastern side of the Rhône was in the territory of Charles of Anjou, Count of Provence and King of Sicily. But Charles was a vassal of the King of France and in Provence Philip’s influence was unchallenged. So Clement was still very much under the thumb, so to speak.

In the Middle Ages it was certainly not uncommon for the Papal court to spend time out of Rome; sometimes disease or fighting made Rome a dangerous place to be, and we have already seen how the court moved to Viterbo for a while. But Avignon was a long way away indeed. Philip’s earlier attempt to abduct Boniface to face a kangaroo court in France would have left no doubt about his determination to exercise control, and now the Papal Curia was in a much more convenient location for him to do so.

So what was Avignon like when this dignity was unexpectedly bestowed on it? Quite a small place, it seems – only about 5,000 inhabitants – but not insignificant. This is because it occupied an important position in European trade; it was situated at the furthest point downstream where the Rhône could be bridged (sort of; see below). Down the Rhône valley came the wool and fabrics of England and Flanders. Up the Rhône from the Mediterranean came manufactured goods from Italy and Spain, over the alpine passes came the grain of Lombardy and the armour and weapons of Milan. It must have been a fairly cosmopolitan place even before the Papal Curia arrived.

But once it had, Avignon was soon bursting at the seams, with one source suggesting that the population rose to around 30,000. The enormous Papal Palace, which still dominates the town, was nonetheless too small to house everyone, and an important official in the Papal bureaucracy was engaged full-time in finding accommodation in which to billet cardinals and their entourages, and the many ambassadors. There are many descriptions of the stinks and filth of Avignon in documents including diplomatic dispatches (it seems it was not a popular diplomatic posting).

Clement’s subordination to Philip IV made him an accomplice in the greatest crime of the 14th Century – the suppression of the Knights Templar. Philip’s earlier unsuccessful attempt to arraign Boniface on fabricated accusations shows his style. This time the charge sheet against the Templars included devil-worship, baby-sacrifice and homosexuality, all of which were admitted under torture, although most victims recanted their confessions just before they were burned at the stake. All of this was for no better reason than that the order was wealthy and powerful, and Philip wanted that wealth and power for himself.

It is quite common to see this period described as a “Babylonian Captivity” of the Papacy, but that is a bit misleading. The Pope and the Papal Court were all quite happy to be more or less in France, not least because the Pope chose the Cardinals, and in a short time the Cardinals were almost all Frenchmen, just like the Pope (in another extraordinary coincidence, four of them were also his nephews).

And it seems that the experience of living in Avignon was improving as well. The overcrowded and smelly village of the early years had been replaced by a large and very wealthy city, with fine palaces for cardinals and ambassadors. The sudden increase in Avignon’s status only increased its importance as a trading centre. Not only was it still on all those major trading routes, but there were now a lot of very rich churchmen there competing with each other to display conspicuous wealth. This drew many Italian merchants to Avignon, including Francesco di Marco Datini, the “Merchant of Prato” of whom Iris Origo wrote. I mentioned that book in my article on her, and it contains some interesting descriptions of Avignon around this time.

The poet Petrarch was not a fan. He lived there briefly as a child with his family, then returned as he travelled Europe as a scholar and ambassador, and stayed with one of the cardinals in the town of Vaucluse nearby. As an Italian he could be expected to disapprove of the idea of a French Papacy, but as a Franciscan he was genuinely shocked at the luxury and indulgence:

Here reign the successors of the poor fishermen of Galilee; they have strangely forgotten their origin. I am astounded, as I recall their ancestors, to see these men loaded with gold and clad in purple… Instead of holy solitude we find a criminal host with crowds of infamous cronies; instead of soberness, licentious banquets…[1]

Petrarch went on to say that at this rate even the horses would be shod in gold before long. One of the later Avignon popes, John XXII, was indeed famous for hosting stupendous banquets – and also for ensuring there would be enough for the guests to drink by founding the vineyards of Châteauneuf-du-Pape (“the new castle of the Pope”).

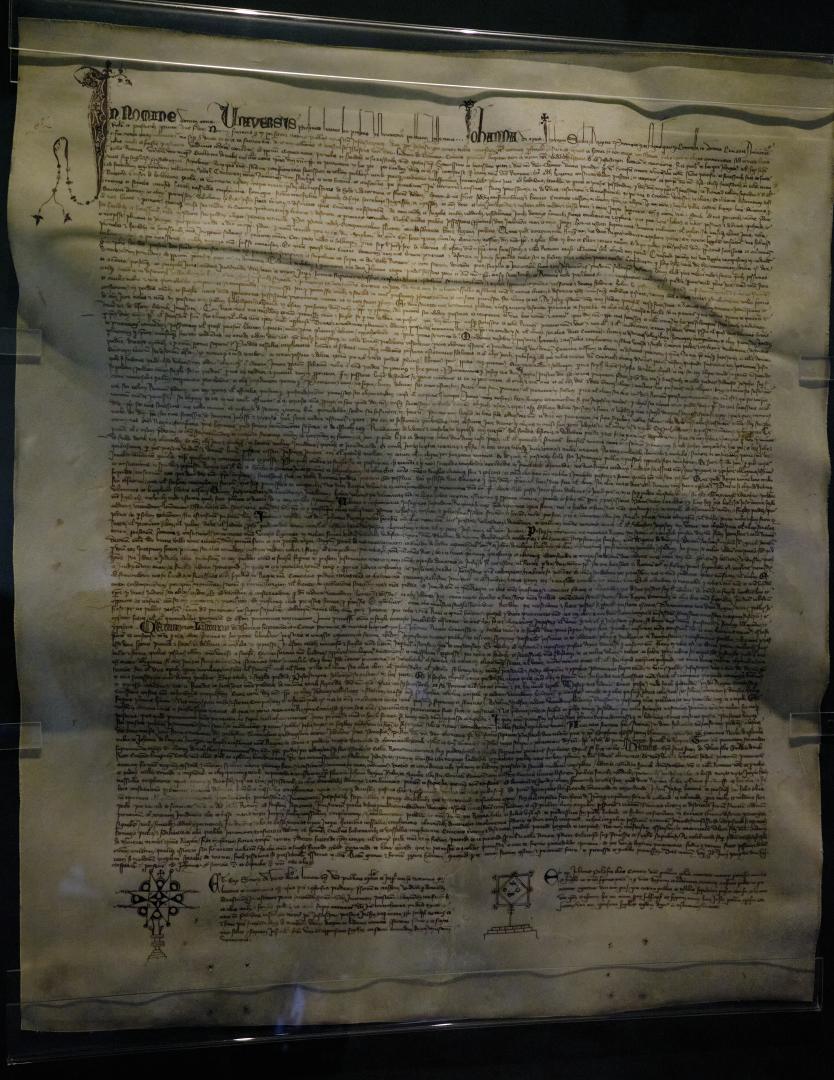

To answer my original question, the reason we are talking about Avignon in a blog about Italian history is because in 1348 Pope Clement VI bought Avignon and the territory round about from the Angevins – Queen Joan of Naples, to be precise – and it then became an exclave of the Papal States. It remained so long after the Papacy returned to Rome, and only became incorporated into France at the revolution in 1789.

We visited in October 2023, driving into France from Piedmont, which I wrote about in Wine and Truffles in the Langhe. Rather than take the main motorway and the tunnel under the Alps, we took the slower but far more picturesque route over the pass of Montgenèvre, and in doing so inadvertently followed one of the trade routes that made Avignon wealthy.

We stayed a few kilometres out of town in the Châteauneuf-du-Pape wine region (for historical research purposes only, you understand). Getting into Avignon was easy enough, and there are underground garages in walking distance from the centre, or open garages on the island in the middle of the river, with a shuttle bus into town, so it is fairly well-organised.

The Papal Palace dominates the town, and is quite spectacular, as you might expect. It is after all the largest example of medieval gothic architecture in Europe.

There was a bit of a queue for the palace, but not too bad. Inside several school groups were causing congestion, but eventually we managed to find ourselves in a space between two groups which improved things.

Lots of museums these days seem to feel the need for high-tech gimmicks, and in this case the gimmick was “augmented reality” where you were given a tablet and in each zone you would point it at a QR code. You could then point the tablet in any direction and it would display a computer-generated image of what that view might have looked like in the 14th Century, with furniture, wall hangings and so forth. In a banquet hall you could see a banquet in progress (perhaps one of John XXII’s famous blowouts). The CG images were not too cheesy and seemed to be based on actual research, so it wasn’t too bad, and kept the kids interested.

For us the best bit was the outside area, where they have recreated a medieval garden, with medicinal herbs, fruit trees and the like. It was a pretty, peaceful place, and best of all the schoolchildren weren’t interested and kept going.

You can’t visit Avignon and not visit the bridge, even if it means that you will be humming “Sur le Pont d’Avignon” to yourself for the rest of the day. The famous bridge actually predates the Papal period by a couple of hundred years, having been built, as I said, at the point furthest downstream where the Rhône could be bridged (thanks to the island in the middle). Unfortunately it was actually a bit too far downstream for safety, and after it suffered repeated flood damage and was repeatedly repaired over the years, people eventually gave up trying to rebuild it when a flood carried away 18 of the 22 arches in the 17th Century.

It’s not a bad place from which to look back at the town and the palace, and to think about the tumultuous period when power politics and religion collided here.

The Avignon period was to last 68 years, officially (there was a confusing bit at the end when rival popes operated in both Avignon and Rome). The eventual return of the Papacy to Italy, and the military and political subjugation of many central Italian cities in the process, is an interesting enough topic to merit its own article one day. Edit: here is that article.

[1] Quoted in The Popes by John Julius Norwich. According to Norwich’s bibliography the translation is by E.H. Wilkins.

One Reply to “The Avignon “Captivity””