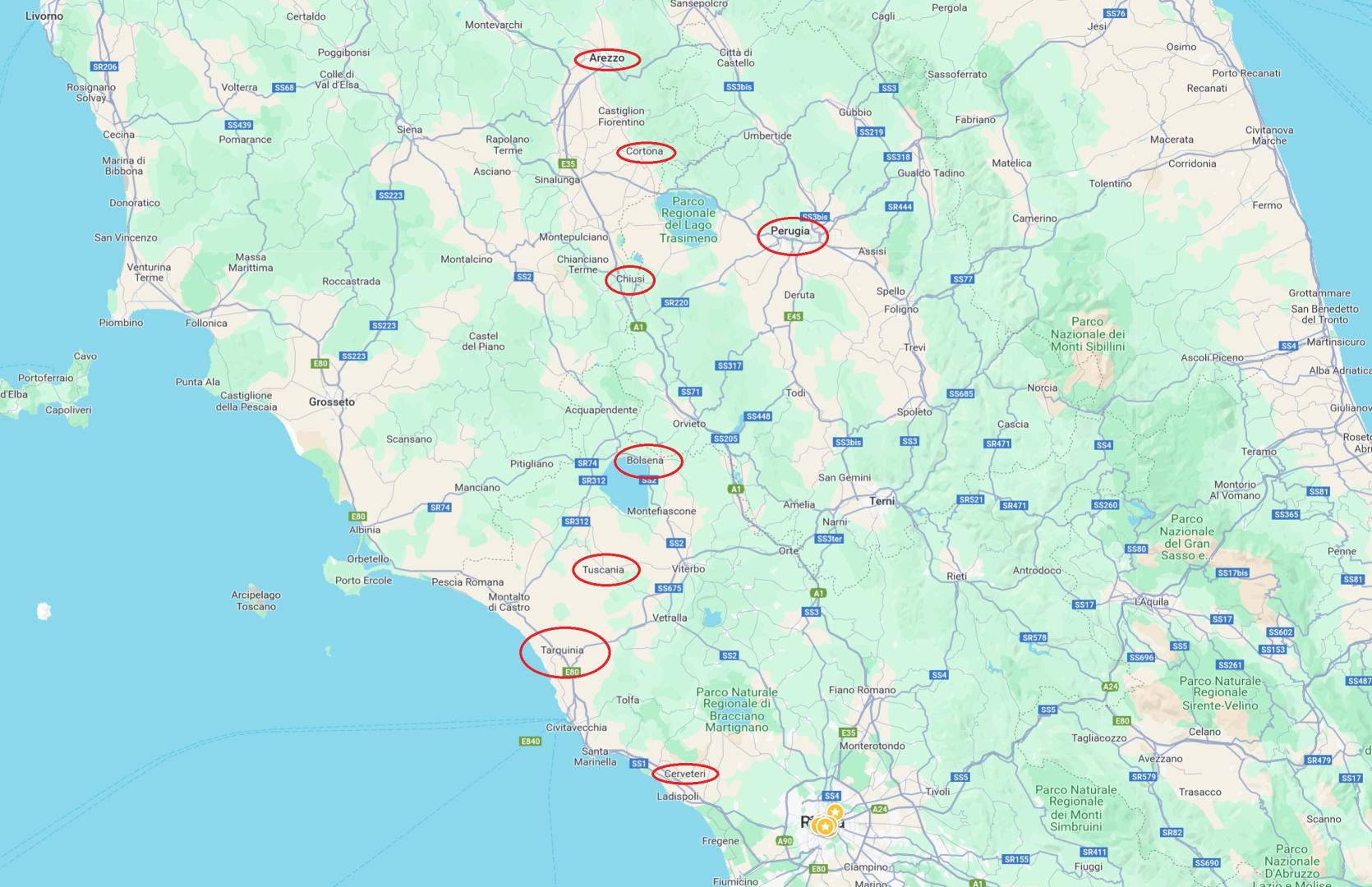

In 2019 we made a visit to Tarquinia in northern Lazio to see the famous Etruscan necropolis. This is intended as a follow-up to a piece I wrote in 2021 about the Etruscans, titled “Lars Porsena of Clusium, by the Nine Gods He Swore”. That was largely built around a visit to an Etruscan tomb of comparatively recent discovery, near the town of Sarteano, and a visit to Chiusi, one of the 12 principal cities of the Etruscan homeland (and the “Clusium” of the poem by Macaulay from which I took the title of the article).

Another of the 12 cities of the Etruscan League was Perugia, which I can see in the distance from where I am writing this in 2024, although I am in the territory of the ancient Umbri on the other side of the Tiber.

A brief history, even briefer than in the earlier article, is that linguistics and DNA analysis of archaeological remains tell us that the Etruscans were for all practical purposes autochthonous to west central Italy, pre-dating the arrival of Indo-Europeans. They developed from an earlier Bronze Age culture called the Villanovans, and at their height their domains stretched from the Po Valley in the north to the coast south of Naples. Rome was part of their territory, and, of course, grew to rival and then dominate them – although the heroic tales which later formed part of the Roman “history” of writers like Livy can only have been true in the broadest of senses.

Although Rome bested Etruria militarily, Etruscan civilisation did not perish in flames. Instead it gradually became ever more Romanised, until Etruscan language, customs and people’s names ceased to be recognisable as such. The result was mostly but not entirely Roman, although with the exception of a few words of Etruscan origin, it is impossible to know how much Etruscan culture contributed to the synthesis.

“Tarquinia” is the name given by the Romans to the Etruscan city probably called Tarchna, which was also one of the Etruscan League. You will also recall that some of the Etruscan kings of pre-Republican Rome were called Tarquin. It seems extraordinary that the name should have survived unchanged from antiquity… and of course it didn’t. It was known as Corneto until 1922, when the Fascists, in their enthusiasm for ancient glories, changed the name back to the Roman version.

In Italy, the taste for antique Roman references, like Ferragosto for the August holiday, survived the fall of Fascism, so Tarquinia it remains.

On the way we passed the Lago di Bolsena, the lake named for the town of Bolsena – Roman Volsinii and before that Etruscan Velzna, another of the cities of the Etruscan league. It is a very beautiful area, even with the wind farms on the horizon, and it is not hard to convince oneself that the Etruscan heartland must have been quite an idyllic place.

Tarquinia

Tarquinia is located on high ground overlooking the nearby Tyrrhenian Sea – so the restaurants offer excellent seafood. It is a pretty mostly-medieval town with a few towers of the sort you find in San Gimignano, although not as tall.

We stayed in a B&B called “Antiche Mura” (the old walls). This was an accurate description as it was in a building just inside the old town walls, which offer a palimpsest of medieval bits on top of Roman bits on top of Etruscan bits on top of a small number of Bronze Age (Villanovan) bits.

The couple who ran the B&B were very nice and have a son who is living and working in Melbourne, so on the basis of that indissoluble bond we hit it off quite well. Of course it is not uncommon to meet Italians with friends and relatives in Australia, but it used to be that those friends migrated in the 50s and 60s. These days youth unemployment – in part the result of an over-regulated labour market – is so bad that any kid with a bit of get-up-and-go gets up and goes, creating a whole new generation of reluctant and homesick exiles. At least visits home are cheaper than in the 1960s.

The necropolis is in a field only a few hundred metres outside one of the town gates so the next morning we went there on foot. It was a warm day with bright sunshine and after a wet spring the wildflowers were going berserk, as were the bees. The whole place smelt like millefiore honey. Also going berserk with weed trimmers and tractor-mowers were the groundsmen employed by the council to mow all the grass and wildflowers, which was a bit of a shame but understandable as it would doubtless become a fire risk in summer.

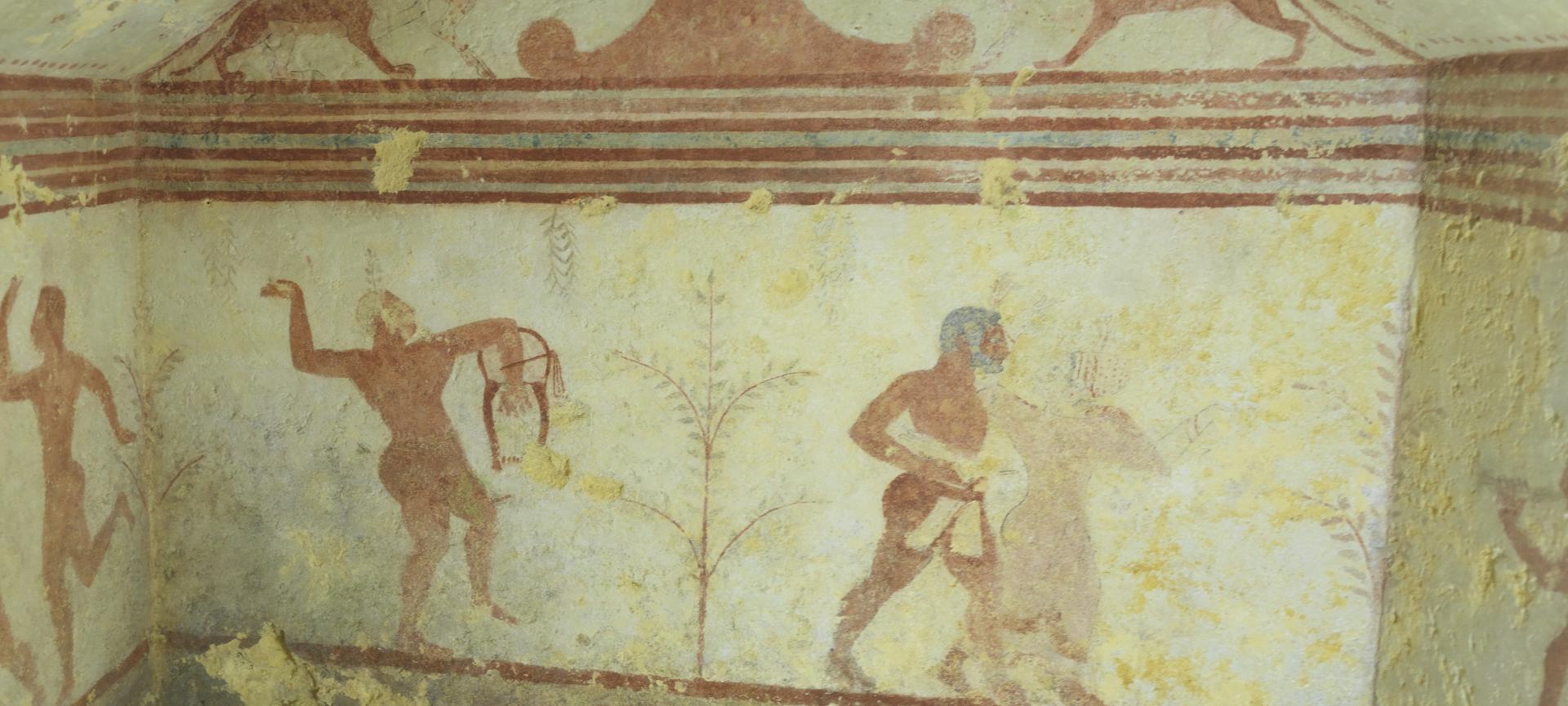

Tarquinia must have been a pretty big place, as demonstrated by the size of its necropolis, which has about 6,000 known graves (of which 24 or so are open to visitors). These mostly date from the 5th, 4th and 3rd Centuries BC. The wealthier Etruscans buried their dead in large walk-in tombs, decorated with brightly coloured frescoes. The tombs in Tarquinia started to be rediscovered in the 1860s, but over the years many have been broken into and despoiled by landowners and grave robbers looking for gold jewellery who discarded or destroyed other relics. And they have been caught up in the illegal trade in ancient artefacts which has seen parts of some frescoes chiselled off and sold overseas. And to complete the sad story, the frescoes in the graves which were uncovered in the 19th Century have gradually faded on exposure to the outside air. In almost every case the colours were much less vibrant than in the Sarteano tomb (excavated in the early 2000s) we visited the previous year.

The tombs are underground and many of them are visible as small humps in the field. Only a couple can be approached by the original long stone-lined passages; most are accessed by steps leading down from a little hut built for the purpose. When you get to the bottom of the steps there is a glass door preventing access to the actual burial chamber, and you press a button to turn on an electric light to illuminate the interior. You then peer through the glass, trying to see past the condensation on the inside and all the fingerprints on the outside left by the last school group. Making decent photographs is challenging.

The paintings are fairly conventional – the spirit of the deceased was believed to hang around the burial place so they tried to paint it to look like a nice place to be. In one case the inside was actually painted rather effectively to look like the inside of a tent pitched on a hunting trip.

In many others the paintings are of banquets with musicians and dancers. But in most, in the centre there is a painted false door that symbolises the door to the underworld, and in some cases there are representations of the demons or demigods who will accompany the soul thither. Historians call these figures Charons, like the ferryman of the Greeks, but these Etruscan Charons tended to have blue skin and drove chariots rather than rowing boats. The Charon in the tomb we visited in Sarteano the previous year had white skin and red hair.

We toiled around the entire necropolis and I went into all of the 24 tombs, while Lou was a bit more discriminating and only went down those which looked good on the signs outside, or if I came back up and reported them as worth seeing.

Afterwards we visited the town museum which is housed in a fine palazzo, much renovated over the years to include renaissance and baroque touches on its medieval base. It contains lots more Etruscan stuff, and also some reconstructed tomb chambers containing the original frescoes which were removed and reassembled inside the museum. Nearby there was a fine gelateria, and there was another even better not far away.

Tuscania

After parting from our hostess with many protestations of mutual esteem, we returned to Umbria via a town called Tuscania (which, confusingly, is not in Tuscany but in northern Lazio). We went there because we had driven through it on the way to Tarquinia and thought it looked nice. As indeed it turned out to be – so we stayed a bit longer and had a picnic lunch in a park.

Tuscania is very ancient but was not one of the 12 cities of the Etruscan league. The area is obviously rich in Etruscan remains though, given the number of sarcophagi and funerary statues dotted around as public decorations. It is one thing to read that there there are a lot of Etruscan remains, but when the town council starts using them as garden ornaments, it does kind of make the point.

Tuscania is quite close to the port of Civitavecchia which is where the cruise ships call in to Rome and it is a destination for coach trips for cruise passengers. A couple of buses turned up while we were there but the occupants were all fairly elderly so we managed to outrun them to the ice cream shop, which was possibly even better than the ones in Tarquinia.