Amalfi is a little jewel of a town on a beautiful rugged coastline which was a major maritime power in the Middle Ages. In 2012 we took a trip around southern Italy; we started with Puglia and the Salentine and now I would like to talk about the Sorrentine peninsula, and in particular its southern coast, called, appropriately enough, the “Amalfi Coast”.

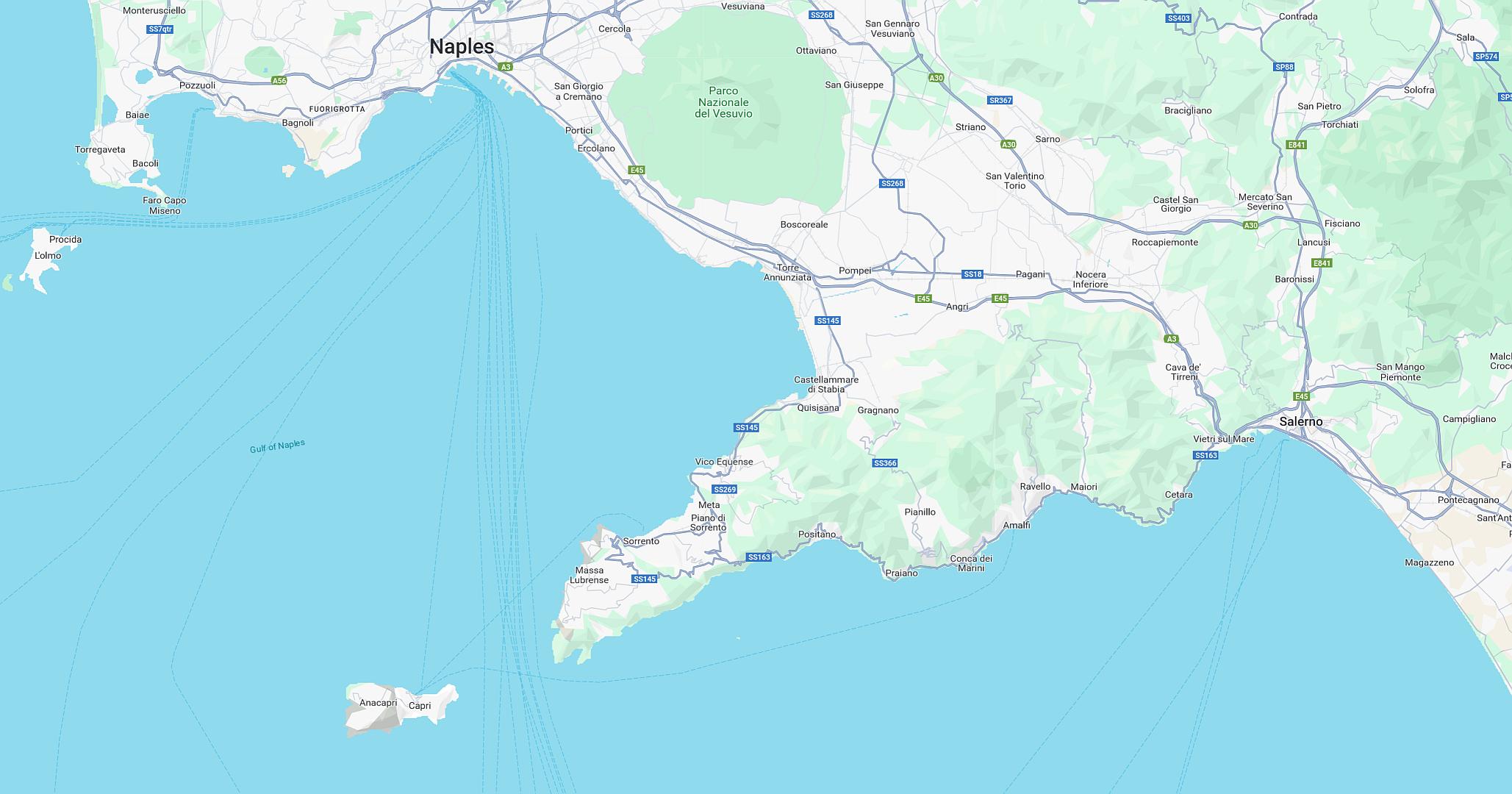

The Sorrentine Peninsula – named for the town of Sorrento on its northern side – marks the southern edge of the Bay of Naples. It is very steep and rugged, and even today is crossed by few roads, so the people who live on the Amalfi Coast have always looked to the sea for transport, and for their livelihoods.

History

In the most ancient period of recorded European history, this area was part of what the Romans would later call Magna Graecia (“Greater Greece”), with many Greek colonies, including of course Naples and Syracuse, and even some Etruscan outposts such as Salerno. But as far as I can tell Amalfi was not one of them, with the first reference to it being in the 4th Century as a trading post. Perhaps it existed in antiquity as a quiet fishing port, just one of many hugging the steep coastline.

But only a couple of hundred years later it had emerged as a significant middle power, a maritime state with the potential to rival Pisa, Genoa and Venice as one of the great “maritime republics”. Exactly why this should have been is hard to pin down for the historical amateur, as it does not seem to be in the most propitious location. But the end of the Western Empire brought new states and new boundaries between them, and where there are boundaries, people will trade across them. And like the lagoons of Venice, the impassable mountains of the peninsula would have protected Amalfi when armies were ravaging the mainland.

Southern Italy had not been spared the ravages of the Gothic Wars, and after the subsequent Lombard conquest most of the south found itself part of the Lombard Duchy of Benevento, with a few nominally Byzantine centres dotted around the coast, of which Amalfi was one. It then came under Lombard rule for a while, before reverting to Byzantium, at least in name.

In time that notional Byzantine suzerainty faded completely and in the 10th Century Amalfi became a duchy that was independent for practical purposes.

Whatever the strategic situation may have been, Amalfi was stuck on a steep rocky coast, which did not provide much in the way of arable land for agriculture. Apparently in the 13th Century the Amalfitani did harness the fast-flowing rivers to power paper mills which created an export industry, but most of the city’s wealth would necessarily come from trading – wheat, salt, slaves and much else, with Arab Sicily and North Africa, the Levant, Sardinia and the Italian mainland. It played an important role in the development of maritime law and trading standards.

In the 10th Century the Arab traveller Ibn Hawqal described Amalfi as “the most wealthy and opulent Lombard city”, and more important than Naples.

The Lombard duchies in northern Italy had been overthrown by the Franks in the 8th Century, which led in due course to the emergence of the Holy Roman Empire. But in the south the contest was between the Lombards and Byzantium, until the early 11th Century, when as I explained in my post on Norman Sicily, the Normans arrived. Within a very short time the Normans under Robert Guiscard had carved out their own state. Guiscard captured Amalfi in 1073, and although there were some short-lived revolts, its independence had pretty much ended. Later it became a possession of Pisa, and in the 1280s there were some hard times in the region due to the War of the Sicilian Vespers.

Amalfi’s wealth did not end immediately with its loss of independence, although it did start to decline. It continued to play an important part in Mediterranean trade, developing the box compass, and maintained its leading role in maritime law. Then in 1343 it all ended in a single day. An earthquake sent half the town into the sea, and the accompanying tsunami destroyed what was left of the port. Amalfi ceased to exist as a trading city.

The abrupt end of Amalfi had one benefit for posterity: the part of town that survived contains some very distinctive architecture that is characteristic of the period and the region. Had Amalfi’s prosperity continued, it would doubtless have been at risk of modernisation at some point in the subsequent centuries.

For centuries the coast remained a backwater, then during the period of Napoleonic rule in Naples, Joseph Bonaparte decided to commission a road from Sorrento to Salerno along the coast. It took decades to build, and was only completed shortly before Italian unification in the reign of the Bourbon King Ferdinand II in 1854. The road was only built to be wide enough to fit the royal coach, which was fine until tour buses arrived in the 20th Century. These days it is a bit hair-raising to drive along – you quickly learn to look in the convex mirrors mounted at the hairpin bends, because if you are halfway round and you meet a bus coming the other way, it is you that will be reversing. In the last couple of years the local government has imposed restrictions on car traffic – in peak season visitors can only drive on odd or even dates, depending on their licence plates.

Anyway, once the road was completed the area was opened up for visitors, and the spectacular coast became a destination in its own right. Various luminaries including Richard Wagner spent time here. Later, towns like Positano and Ravello as well as Amalfi became resorts for the wealthy.

Nowadays tourism has brought wealth back to the coast, but I have read stories from as recently as the 1950s and 60s of people living here in great poverty.

Pogerola and Amalfi

We were staying in a village called Pogerola almost directly above Amalfi. We arrived having driven for several hours from Puglia in terrible weather, and my first impression of Pogerola, as I made several trips ferrying bags several hundred metres down from the car in heavy rain, was not favourable. Our accommodation was one of the smallest places in which we have ever stayed in Italy, with only a sofa bed which we needed to fold away in the morning in order to be able to move around the room. But it had a terrace with a panoramic view, and the owners were friendly and had stocked the kitchen with various local delicacies so we did at least feel welcome.

The owners also advised me where to park – it was signed as two-hour spot but I parked there for a week without adverse consequences. There is no substitute for local knowledge.

The next day was sunny and we forgave Pogerola everything from the night before. There was a remarkable view over the Tyrrhenian Sea, deep blue and dotted with pleasure craft but also cargo vessels of various sorts hurrying back and forth between Naples and Salerno.

Looking about us we saw many terraces built out from the steep hillsides, mostly covered in black nylon netting. These were where lemons were grown, and the netting was presumably because at the end of April it was still cool enough for there to have been a risk of frost. The lemon trees, and lemon-based products, are everywhere. And such lemons – sweet rather than sour, with thick edible pith.

Pogerola is quite close to Amalfi, in fact a running jump and a fall of a few hundred feet would have got me there quite quickly. And since parking was going to be very difficult in Amalfi, it seemed a good reason to go there on foot. This was an opportunity to acquaint myself with the narrow and steep paths that were the only access to the hillside villages until comparatively recently. These are still in use – at one point I passed someone delivering sacks of cement to a building site, carried by a pair of pack mules.

Later, on my way back up the hill, I was making much slower progress. At one point I was pausing to try and catch my breath when down the hill at great speed came a sprightly octogenarian. He was about five feet tall, or at least he would have been had he not been bent over under the weight of a large basket of lemons. I tried to stop panting long enough to wish him a buona giornata, to which he responded affably but in (to me) an incomprehensible dialect. We later discovered that this old gentleman walked down from Pogerola to Amalfi every day with his basket of lemons to sell, and then, more sensibly than me, took the bus back up again.

On another day we did take the bus. The road down into Amalfi was even more narrow and winding than the main coast road, and inevitably when we were halfway down the bus met a truck coming up the other way, with no room to pass and a line of cars and scooters behind both, which made it difficult for either to reverse. In a long, complicated and frankly unbelievable manoeuvre, both drivers managed to work their vehicles back and forth and eventually, with only a few centimetres between the walls and the two vehicles, past each other. In this our driver was assisted, possibly, by a bunch of old blokes from the village who were sitting at the back of the bus and yelling out things like “Vai, vai, Luigi! Aspetta! Vai!” and enjoying themselves thoroughly.

In fact we had already realised that driving on the roads of the Sorrentine Peninsula requires a good deal of patience. At one point we had been driving up a steep and narrow road and came to a village. There was a small truck in front of us that had lots of crates on the back. On entering the village it stopped in the middle of the road, and sounded its horn. Unable to pass, we watched the greengrocer – for such it was – negotiate a shouted transaction with a lady on a balcony, who then lowered a basket with money in it, and raised the basket again with her vegetables. Fortunately we were not in a hurry, and it was more entertaining than being stuck in a traffic jam of tourist buses down on the main road.

Once the bus had dropped us down in Amalfi we split up and I slogged up a lot of steep alleys on the eastern side of the town in the hope of getting to a vantage point looking over the town with the morning light behind me. Despite my increasing fitness this was not particularly easy, as I was carrying my complete large format camera gear: body, sheet film magazines, three different backs for various film formats, six lenses and shutters on lens boards, and a tripod and head. Probably 20kg or more in total. These days my photography gear is much lighter.

Eventually I found just such a lookout and took several pictures. Even working quickly, taking a single large format photograph takes a few minutes, as I explained in my post titled Crocodile Dundee Shoots Large Format. I went back down into town where we rendezvoused in a bar for coffee and a cake, and then we went to the cathedral which dates from Amalfi’s days of wealth and power. I’m not an architectural expert but it does look quite exotic, with several stylistic features which I took to be Norman-Arabic.

After that we walked around to the next little town (Atrani) and I took a couple more large format photographs.

Then we decided to catch the bus back up to Pogerola for lunch. The trip back up started dramatically. There was a bit of a traffic snarl-up in the centre of Amalfi due to another bus impasse a bit further up the hill. One of the local cops was trying to sort it all out and getting a bit exasperated with all the scooter riders who were weaving between the other vehicles and around him, without taking much notice of any of his signals. Just as we were starting to get moving there was a thump and the bus stopped suddenly amid much consternation. We thought the bus might have hit one of a couple of cyclists who had been trying to get across the road, but it turned out that one of the scooter riders had misjudged his weave and hit us. A crowd of people picked him up and dusted him off and he seemed OK. As we pulled away the policeman had whipped out his notebook and was taking the rider’s details, doubtless pleased to have caught one of them at last.

2 Replies to “Amalfi and the Sorrentine Peninsula”