Viterbo is a substantial town about eighty kilometres northwest of Rome, with some interesting history and historical sites. In the 13th Century it was the scene of a rather farcical stand-off involving the election of a Pope and the removal of a roof.

The more recent history is not inspiring. After the German army abandoned Rome in 1944 they set up their headquarters in Viterbo, which led to it being heavily bombed. Many ancient buildings were destroyed or damaged – in fact in the duomo or cathedral most of the columns have chunks of stone missing as the result of bomb explosions. When the rest of the building was repaired they decided to leave the columns as they were, as a reminder.

These days Viterbo is a provincial capital in northern Lazio (the region that includes Rome). The growth associated with that, and the post-war reconstruction, has led to a lot of unappealing urban development around the historic centre. But the medieval stuff that was preserved, or has been restored, is worth the trip. The centro storico has a pleasant, relaxed air.

Entering the centro storico from the north, the first substantial buildings you get to are the Palazzo del Podestà and the Palazzo dei Priori, built as the seat of municipal government in the Middle Ages, and as in so many other Italian towns, still serving that function, although the medieval architecture of the originals was modernised during the Renaissance.

You see lots of lions in one form or another on these buildings, as the lion is the symbol of Viterbo and is featured on the town’s coat of arms.

A few minutes’ walk from the Palazzo dei Priori brings you to Piazza San Lorenzo, where you will find the duomo and the Palazzo dei Papi (Palace of the Popes). Here, apart from the baroque facade of the duomo, everything is more starkly medieval.

In the 13th Century the situation in Rome became a bit unstable due to fighting between powerful families, so the papal court decamped to the comparative security of Viterbo, where a palace was built to house the Pope and his administration.

The Palazzo dei Papi is a forbidding-looking building. The uniform greyness of the local stone doesn’t help, but nonetheless one comes away with the impression that the 1260s were not a time of conspicuous gaiety. At one end of the building there is an interesting loggia, alas partly covered by scaffolding at the time we visited.

Not all the building works in the papal palace were successful. One of the Viterbese popes, John XXI, died from injuries sustained when a new roof collapsed on him while he was asleep in bed.

In 1269-71 the palace was the scene of a rather infamous papal election, which remained deadlocked for two years due to intrigues, bribery and power politics. As I recall reading, the French bishops were under orders from the King of France not to vote for anyone but a Frenchman, and the others wanted anyone but a Frenchman.

The elector bishops looked like staying deadlocked, until the governors of Viterbo started to get tired of it all (the electors and their substantial entourages were after all being lodged at public expense). First the town authorities locked the delegates into the great hall of the palace. When the bishops did not take the hint, the governors then ordered that the roof of the hall be removed, whereupon the bishops pitched tents in the hall in order to shelter from the rain (the holes for the tent pegs can still be seen in the flagstones).

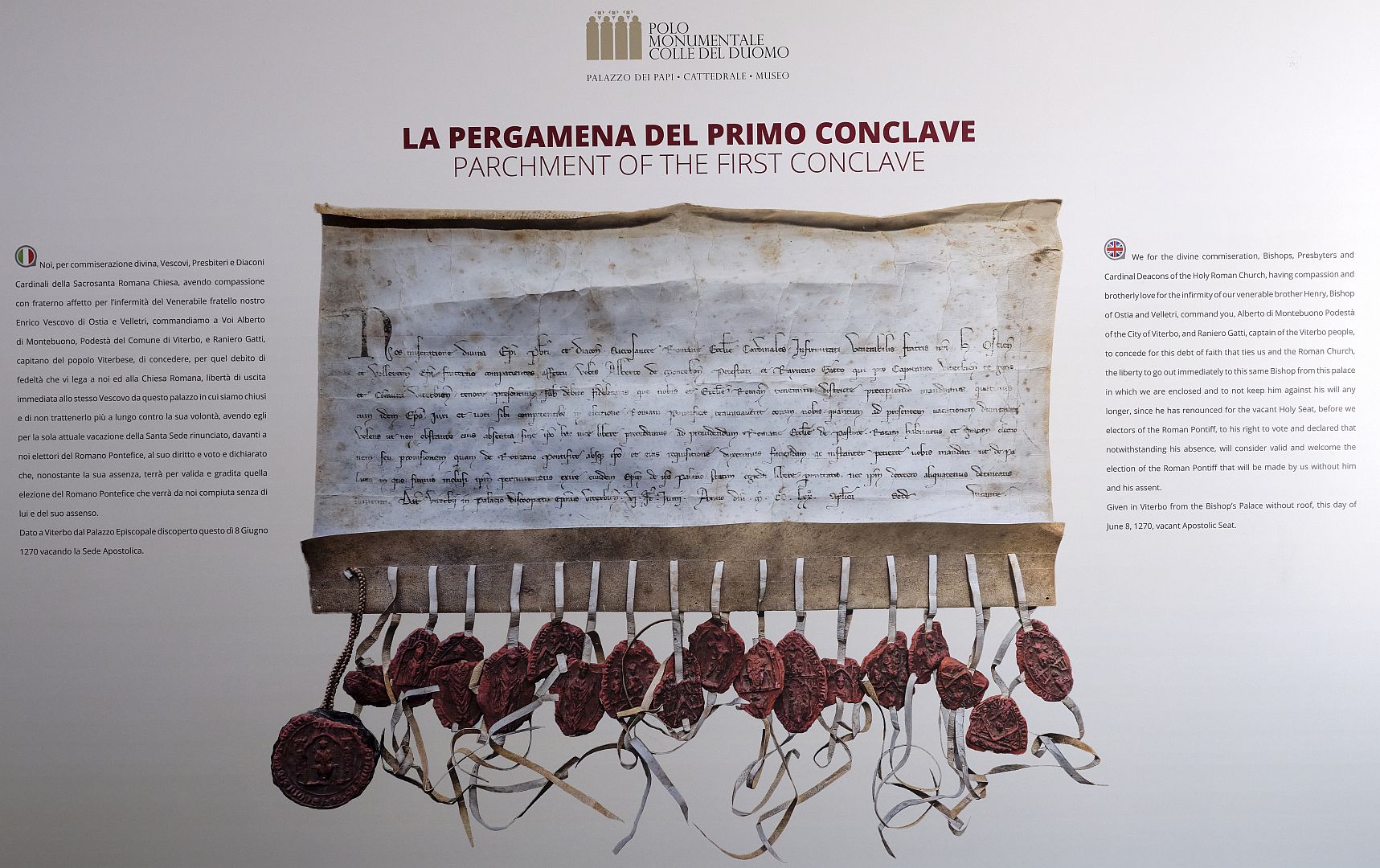

On display in the hall you can find a letter to the governors from the bishops, asking that one elderly bishop be allowed to leave on account of his age and infirmity, and on condition of his having renounced his right to vote.

Finally the food supplies were reduced to minimum rations, at which point the bishops gave up and chose Gregory X (not French). Gregory is mostly now remembered for changing the procedures for papal elections to something pretty much like those used today, in order to avoid similar impasses.

A succession of Popes ruled from Viterbo for a while before returning to Rome. However in 1309 Pope Clement V (a Frenchman) moved the Papacy even further away to Avignon, so the French won in the end.

After poking around the Papal Palace, the Duomo and the municipal museum, we found lunch in a trattoria in a nearby square. Despite not being far from Umbria, we have noticed before that when you cross the Tiber valley into Lazio, the cuisine changes a bit – in particular there is a lot more seafood on the menu.

For us, another attraction of Viterbo is the picturesque medieval quarter, along the Via San Pellegrino. It is understandably in regular demand as a film set.

We spent a pleasant afternoon wandering along Via San Pellegrino and the side streets that run off it. It all looked very nice in bright sunshine, although on a rainy night one might think back to those bishops and cardinals sulking in their tents in the roofless hall of the Palace of the Popes.

One Reply to “Viterbo – Wet Bishops in the Papal Palace”