There are all sorts of reasons – geo-political, cultural, artistic – why the brief period of Norman rule in Sicily should be better known than it is. There are not many histories of the subject in English, and by far the best is that by John Julius Norwich, originally published in two volumes (The Normans in the South 1016-1130 and The Kingdom in the Sun 1130-1194) and later as a single volume titled simply The Normans in Sicily. This is one of my favourite books and I would recommend it to anyone just for the quality of its writing, but it is an absolute necessity for anyone who wants to understand Italy in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Lord Norwich’s writing is as elegant and engaging as always, but it is also an extraordinary story. How did one of the younger sons of a minor and impecunious family in Normandy, the de Hautevilles, found a dynasty that – almost a thousand years ago – synthesised French, Italian, Greek and Arab cultures into a sophisticated and tolerant regime? A dynasty that dictated terms to popes, built some of the most beautiful buildings anywhere, and which – through the female line – produced the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen, a polymath known as Stupor Mundi, the wonder of the world.

Well, Norwich takes two rather substantial volumes to tell the story, so I’m not going to do it in a blog post. But here’s a very quick sketch.

In the former Lombard duchy of Apulia (the modern Italian region of Puglia), temporarily re-absorbed into the Byzantine Empire, the Lombards were trying to take back control and sought the assistance of some Norman knights returning from the Holy Land. Word got around back in Normandy and one of the adventurers who appeared was Robert Guiscard (“the crafty”) de Hauteville who soon started carving out his own dukedom in the South of Italy. One of the Norman knights who joined Guiscard was his younger brother Roger.

Sicily was then under Arab rule and in due course Roger mounted an expedition to take control of the island. After several years of campaigning he succeeded. Roger only ever held the title of count but his son, Roger II, was recognised as King of Sicily by the Pope.

Rather than exterminate, exile or marginalise the Arabs and Greeks on the island, Roger I and Roger II allowed free exercise of religion and employed members of both communities, along with northern Europeans, in their governments.

Roger was followed by William the Bad (not really that bad) and William the Good (not really that good, but his reign was marked by peace). During the reigns of both Williams the most powerful courtier was a cleric whose name has come down in Sicilian history as “Gualtiero Offamiglia”, but that is an Italianisation of his real name, Walter of the Mill – he was an Englishman. You never know when knowing that fact will come in handy.

William II died without direct heirs, and the throne passed to his aunt, Constance, who had married Henry, the son of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (see post on Val d’Orcia). Constance’s son became Frederick II, on whom I will write a separate post one day. I’m still looking for a really good biography of Frederick II in English.

The Normans ruled the whole island in the end, but their major architectural legacy is in the northwest – places like Palermo, Monreale and Cefalù. I had assumed that this was because their power was centred on Palermo, but I suppose it could be possible that over the centuries earthquakes in the southeast have destroyed any Norman buildings that were there.

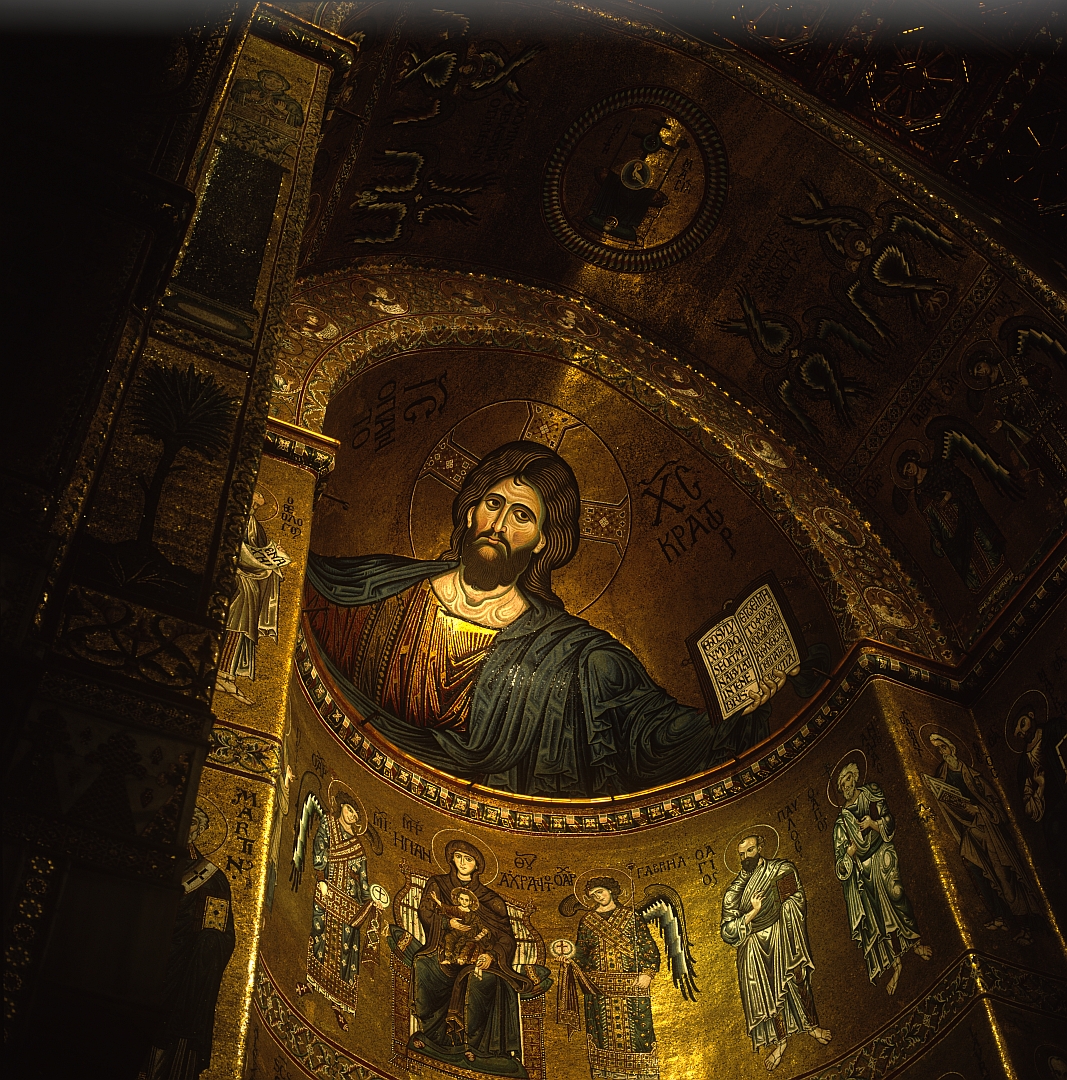

But what a legacy it is. The combination of huge Norman buildings with Byzantine and Arabic decoration is extraordinary and the visual demonstration of this syncretic culture is more eloquent than many thousands of words.

And the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Yes, Byzantine mosaicists were better than their western European contemporaries in the 12th Century, but in the giant images of Christos Pantocrator in Monreale and Cefalù they were not creating images in the formal, mystical and remote eastern tradition. They were working to a very different brief – showing the western preoccupation with the humanity of Christ, and they succeeded in a way that other European artists would not even begin to approach until Giotto came along two hundred years later, and perhaps not even then.

We started with the Palazzi di Normanni in Palermo, with its Cappella Palatina or palace chapel, then later visited the cathedral in Monreale, in the hills overlooking Palermo.

In the picture of Monreale below, you can see a portrait of King William the Good himself, presenting the church to the Virgin. Presumably this was done during his lifetime or shortly after. And what an exotic oriental monarch he looks! His great-grandfather was born in a small manor house in Normandy, but the figure here is far from the conventional image of a Norman thug in a chain-mail hauberk.

Later we visited Cefalù on the mid-north coast – built on the orders of Roger II to house his sarcophagus, but despite that his heir buried him in Palermo.

There are two places in Palermo of which I wish I had photos to show you. One is a church called the Martorana, which was closed for restoration when we were there. The other is an absolute jewel box in the Palazzi Normanni called “King Roger II’s room”, which we did visit, but since I seem to be one of the only people in Italy (tourist or local) that obeys “no photography” signs, you’ll just have to visit it yourself. But here’s a hint – the illustrations on the cover of Norwich’s history, shown above, come from there.

Update: In July 2024 we revisited Palermo and I was delighted to find that the “no photography” rule in King Roger’s room no longer applied. You can find a post with photographs of it, and updated photographs of other places mentioned above, here: A Return to Palermo.

9 Replies to “Norman Sicily”